No church in the wild

Has middle-class atheism run its course? Despite decades of declining population share, Christianity appears to be having a moment with millennials and zoomers. North & South speaks to some of these 20-somethings to discover what Christian faith offers young Kiwis in 2023.

By Theo Macdonald

New Zealand is one of the most secular nations in the world. From 2001 through 2018, according to Stats NZ, Kiwis who identify as non-religious rose from 29.6 per cent of the population to 48.2. When the results of the Christianity is the religion that has taken the biggest hit. Between 2013 and 2018, the proportion of people identifying as Christian fell, while Hinduism and Islam grew. One North & South staffer recalls the rector of his Catholic high school in the mid-2000s in tears over the realisation that not a single student had taken the cloth under his stewardship. Although New Zealand remains a Christian-influenced culture in many ways, as is apparent in the preeminence of the Christmas season, an observed Christianity is becoming increasingly niche.

But, with these trends acknowledged, it also feels like there’s a change in the air; something in the holy water. Uninterested in Gen X’s cynical materialism, millennials and zoomers are expressing warmer feelings toward Christianity’s unrepentant sincerity. A survey in the United Kingdom last year observed that more young people (one in three 18-to-36-year-olds) were praying than 20 years earlier.

Maybe it’s to do with the influx of American pop culture. Superstars of the past 10 years (including Drake, Justin Bieber, and Kanye West) rap on Christian themes. With climate change a primary anxiety for younger generations, perhaps there is also appeal in the Catholic Church’s prioritisation of environmental stewardship, dating back to the ecological commitments of Pope John Paul II. It might also be the internet. More easily than ever, young people can encounter the overwhelming suffering of the world, and Christian influencers often speak in languages of agency and fulfilment. A church in which one is required to (quietly) accept the company and personhood of “sinners”, from sexual abusers to homophobes, works in drastic contrast to the hypercritical echo chambers of online discourse.

Whatever the cause, young Kiwis who grew up non-religious or broke from their family’s faith are discovering new pathways to, and through, the Church. To find out why, North & South reached out to young Christians, clergy and more. Here are their stories.

A disclaimer: some names have been changed to allow our subjects to speak freely. Our focus was on young people who didn’t grow up in the church or now attend churches separate from those they grew up in. As such, our subjects are of European and Māori ancestry. New Zealand’s prominent Asian and Pasifika Christian communities, in which faith tends to be intertwined with family and social life, were not the focus of this investigation.

Rev Cate Thorn

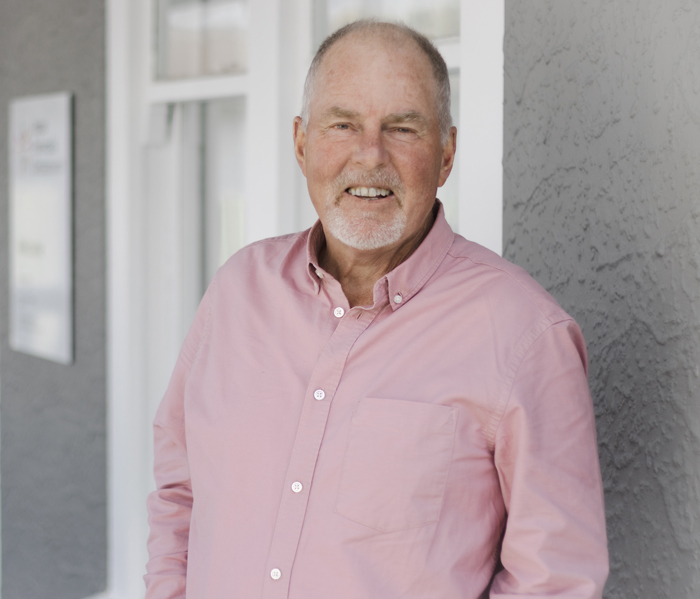

Rev Hamish Galloway

When North & South asks Rev Cate Thorn, priest-in-charge at Auckland Anglican Church St Matthew-in-the-City, whether she’s observed an uptick in younger-generation attendees, she points out that they don’t tend to log the age of parishioners. However, she has observed changes in the younger end of the congregation in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic. More couples in their 20s and 30s seem to be attending services, from a broader range of ethnicities; colleagues overseas have corroborated these anecdotal observations.

In the past few years — an era of high anxiety — Thorn has also noticed young people from evangelical backgrounds joining churches with older, embedded traditions, such as Anglicanism and Catholicism. These more established churches tend to have deeper traditions of question-asking, compared to newer churches’ focus on explanations. “People want to ask questions and have someone engage in those questions.” A prosperity gospel — the belief in divine favour practised in some evangelical churches — doesn’t ring quite so true after the pandemic demonstrated that misfortune can happen indiscriminately.

The Anglican Church, specifically, evolved in the English village, and membership involved regular attendance. For young people, Thorn observes, belonging to a church is less about joining a club and staying there permanently, and more about participating genuinely for the period they need, be that years, months or days. In her discussions with younger members, Thorn says, once you unpack the associations of guilt and sin, the conversations are often about more general problems of being human rather than specifically religious concerns. These conversations are in a “religious patois” because the Church is seen as a safe environment for discussing one’s troubles.

The Right Rev Hamish Galloway is the former Moderator of the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand, an elected position with a two-year term — his term finished in September 2023. Galloway has had a varied career. Prior positions include chaplaincy at St Andrew’s College and in the army, allowing him to observe generational changes in Christian youth since the late 80s. He says the Presbyterian Church still has many young people joining the fold, but there has been a solid generational decline. While Generation X was aware of the Bible, or at least the stories of the Old Testament and Jesus, millennials are largely disconnected from this context.

With membership decline, the two remaining growth centres for younger generations are Pasifika churches (although these parishes are under pressure) and particular urban churches, generally one per city, that have succeeded in pivoting toward a younger audience. The churches drawing in younger attendance, including Hope Presbyterian Rolleston, where Galloway was senior pastor for nine years, are meeting the needs of younger generations through youth groups and youth pastors, and by speaking on subjects of concern for younger people, particularly te reo Māori and the environment.

Like Thorn, Galloway observes that millennials, raised in a world influenced by postmodernism, prefer questions to answers. He says the young remain interested in the same big questions as ever: Where do we come from? Why are we here? Where are we going? It’s where (and how) they look for answers that has changed.