A terrible trap

As more countries move to restrict the use of puberty blocking hormones for children with gender dysphoria, use in New Zealand continues to increase. Charlotte Paul says our health authorities must act.

By Charlotte Paul

A year ago, I called for a review of the use of puberty blocking hormones for children with gender dysphoria.

Writing in another publication, I stressed that there were two moral considerations: we should respect people who identify as trans and protect the best interests of children and young people. We needed a frank and fair discussion, to protect both children and adolescents.

The past year has seen a lot of frank and fair discussion — and action — overseas. Regret over gender transition and detransition are widely discussed. More countries are taking action to restrict the use of puberty blocking hormones. But in New Zealand, next to nothing has happened. It is becoming even easier to access these hormones. Standard medical safeguards are being discarded.

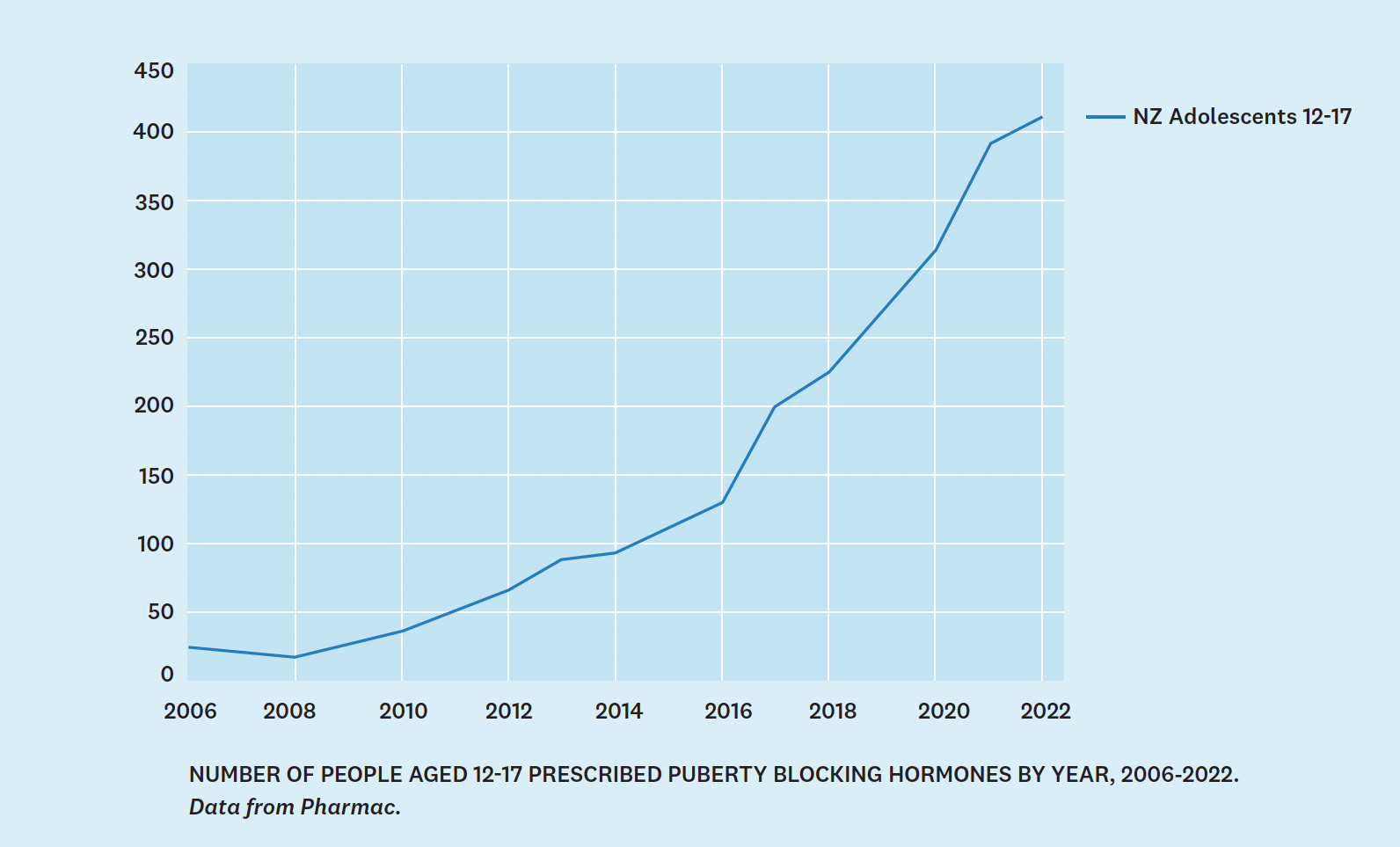

New Zealand is becoming more of an outlier in our increasing use of puberty blocking hormones. In 2022, 416 young people aged 12-17 were taking puberty blocking hormones, compared to 48 in 2011, the first year of use for gender dysphoria. We have 11 times the rate of use as England: 110 per 100,000 versus 9 per 100,000. We also have no minimum age for prescribing. If puberty starts at 10 or 11, these children are eligible for blocker

Comparison with Australian gender clinics (which will underrepresent total use but will show trends) shows a levelling off there since 2018, while New Zealand use continues to increase exponentially (see graph, page 32.)

The gist of my concern is the unknown long- term effects of puberty blockers (gonadotrophin releasing hormone agonists) used to treat children with gender dysphoria, the corresponding need for great medical caution and the apparent absence of it in current medical practice in New Zealand. These hormones suppress normal puberty with the aim of relieving suffering and improving final physical outcomes for those wanting to transition away from their birth sex. What started as a sympathetic stance towards a tiny number of children with lifelong gender dysphoria (distress resulting from incongruence between one’s birth sex and experienced gender) has grown beyond recognition. The context is new: the idea that everyone has a “gender identity” (an inner sense of being male or female or non-binary) that overrides biological sex.

Countries that have restricted the use of puberty blocking hormones have used very different means. The European approach has been through the health authorities. The appropriateness and safety of hormonal treatments for children and young people are being evaluated according to the norms of medical practice. For instance, in 2020 NHS England commissioned paediatrician Dr Hilary Cass to conduct an independent review of gender-identity services for youth. This has removed the issue from the political realm. In sharp contrast, in the US, health agencies have been notably reluctant to discuss the possibility of harm, and the issue has become deeply political. In 22 States there are now legal bans on hormones or surgery for anyone under 18.

My hunch is that the involvement of political parties in enacting laws to regulate medical practice is likely to fuel partisan animosity: greater discrimination against trans people on the one hand, and greater uncritical affirmation of hormones and surgery for trans-identified youth on the other. By contrast, if health agencies act according to professional norms and standards to prevent harm to children, there will be less reason for hostility on either side.

The issue is extraordinarily sensitive. I am aware of hostility to people who are trans. I am aware of the difficulty of living as trans. I am aware that public criticism of treatment practices can feel to some people like an expression of that hostility. These things give me pause. Still I feel obliged to write. Wholly understandable sympathy among doctors for children who identify as trans has led to guidelines and practices that are frankly misleading and likely to do more harm than good.

Last year, I wrote at the urging of younger medical colleagues who feared being labelled as transphobic if they spoke out. They were seeing young people in their clinics who had changed their minds about wanting to transition away from their biological sex and were left with their serious mental health problems unaddressed. They doubted there was sufficient psychological assessment before children were prescribed puberty blockers — to help distinguish those few who will remain transgender from those for whom it is a phase or whose distress has another cause. The landscape was changing: a huge and baffling increase in the number of children and young people questioning their gender and being treated with hormones; a change from a preponderance of boys to girls; and from early to late onset dysphoria. Many of those transitioning are on the autism spectrum and many have underlying mental health problems.

Since I wrote, dozens of people have shared with me their disquiet about puberty blockers for children, and also about cross-sex hormones (testosterone for those born as girls and oestrogens for boys) for young people who were transitioning. Puberty blockers can’t be considered in isolation. The great majority of children taking puberty blockers go on to take cross-sex hormones, and similar concerns about consent, appropriateness, and safety are raised when young people are given cross-sex hormones.

A GP wrote: “Like others I am very afraid that in the guise of helping, medicine may risk doing considerable harm”. Another welcomed my “acknowledgment that a lot of clinicians are fearful of speaking up”. A youth worker told me that his experience of working with marginalized teens closely aligned with what I had written. These teens had “complex histories of trauma, and … an unusually high prevalence of trans-gender identification”. In fact, children in state care are disproportionately likely to identify as trans.

Though it is common to attribute mental health problems of trans people to “minority stress”, the evidence for these young people points the other way: the trauma and mental health problems precede transitioning.

The most troubling responses were from parents who felt sidelined by clinicians who had encouraged their children down a medical path — first with puberty blockers and, once their child was 16, with cross-sex hormones.

The Ministry of Health gave some indications they might re-evaluate their position, but those indications were later walked back. In 2021, I asked the Minister of Health whether a review of the use of puberty blocking hormones was planned in the light of steps being taken in other countries. The answer was no: it was “a matter for discussion between a treating physician and their patient”. In 2022, I called for an independent review and for monitoring. The Ministry, presumably in response to the concerns raised by myself and others, announced it was undertaking an “evidence brief” on puberty blockers. It also instigated some small changes. The description of puberty blockers as “safe and fully reversible” was removed from its website.

In March this year, the Ministry explained to Newsroom: “The September 2022 update to the website recognised that overseas jurisdictions, including the UK and Sweden, were reviewing the use of puberty blockers in their health systems, particularly in younger people”; and, “In light of the relatively limited and thin evidence available in this area, the Ministry’s advice was changed to align better with that.”

Yet by May there was still no sign of the promised “evidence brief”, so I wrote to the Director General of Health again, and to the Medical Council and the Health and Disability Commissioner (HDC). What action would they take given their public roles of protecting the health and safety of patients?

The Ministry of Health indicated it might commission an independent review, but in the meantime is extending work on the evidence brief to the end of the year and including mental health issues. Nothing has emerged to date. Nor will a review of the evidence for benefits and harms of puberty suppression be enough; systematic reviews on this topic have already been published overseas. The Cass review has a much wider focus including making recommendations on pathways to care for gender dysphoria, criteria for referral, models of care, clinical management (including the role of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones), clinical audit and long term follow-up.

The Medical Council responded that it is “able to receive notifications from a range of sources, including the HDC and, where the required standards have been breached, Council can take action to investigate those standards.” Doctors are bound by the Medical Council’s Standards of Good Practice. There appear to be breaches of several standards in relation to prescribing unapproved medicines, assessing the patient’s condition before prescribing, practising in the patient’s best interests, assessing capacity to give consent, and responsibilities to provide accurate and balanced information. Yet so far the Council has declined to investigate. HDC has also declined to investigate a specific complaint alleging lack of informed consent for the prescription of cross-sex hormones to a 16-year-old.

I discovered what is going on in the rest of the world through the mainstream media in other countries. Almost nothing has been published here. Balanced reporting about puberty blockers has appeared in the Washington Post, the Economist, the Australian, and also left wing publications such as the Atlantic, the New York Times and the Guardian.

The March cover of the BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal) was: “Transgender medicine for young people: too far, too fast?” The editor wrote: “If we have the best interests of young people at heart, then surely our duty is to offer evidence-informed care?”, and emphasised the need to provide support to young people in distress, while making research a priority.

This support is being formalised by NHS England, based on interim advice from the Cass Review. The primary intervention will be psychological support. Use of puberty blocking hormones will be reserved for a subgroup of those with early onset gender dysphoria, and only in a research setting. The Cass recommendations focus on the child’s mental health needs: “initially there will be a focus on understanding the expression of gender incongruence and identifying associated physical and mental health and neurodevelopmental needs; and on identifying and responding to clinical risk, including mental health and safeguarding needs”.

A year ago, health agencies in Sweden, Finland, England, and France were re-evaluating the use of puberty blocking hormones. Since that time, Norway and Denmark have announced reviews of their approaches. Interestingly, in Denmark, an alliance of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender groups has advocated for this change.

One of the stimulants for change has been the growing number of voices of those who regret transition — who believe they were caught up in an ideology, and who blame the medical profession for their plight. There are many hundreds of comments like the following on a “Detransition” section of social-media site Reddit:

[N]obody asked me questions. No therapist, no doctor, nobody stopped to ask me, are you sure this is what is right for you? Nobody searched for underlying causes for what I was feeling. Nobody tried to dig deep into my emotions to pinpoint what was really wrong with me, because it wasn’t gender dysphoria. Everyone I saw simply affirmed me. They told me, yes you’re transgender, yes you’re a man….

News organisation Reuters spoke to 17 people who had transitioned as minors and now regretted transition. “Many said they realised only after transitioning that they were homosexual, or they always knew they were lesbian or gay but felt, as adolescents, that it was safer or more desirable to transition to a gender that made them heterosexual. Others said sexual abuse or assault made them want to leave the gender associated with that trauma. Many also said they had autism or mental health issues such as bipolar disorder that complicated their search for identity as teenagers. … Nearly all of these young people told Reuters that they wished their doctors or therapists had more fully discussed these complicating factors before allowing them to medically transition.”

On 3 September this year, Channel 7 in Australia aired a programme that asked if a generation was being brainwashed. The interviews with detransitioners and with parents were bleak and moving. The programme ended with an interview with Professor Ian Hickie from the University of Sydney. Confronted with the stark experiences of those for whom transition was a mistake, Professor Hickie compared their experiences with the risks of any other medical procedures. He then wrote off these risks as inevitable.

Few risks of harm are inevitable. Those who regret transition have experienced harms that should be classed as adverse effects of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. We study adverse effects primarily to take action to prevent harms. The first step might be to warn of the risk before consent is sought. If the harm is severe and irreversible, further action should be taken; the medicine might be withdrawn or its use restricted to a specific group for whom there is evidence it is safer.

For instance, in 2000, when my colleagues and I confirmed that third generation oral-contraceptive use (compared to second generation) doubled the risk of death from pulmonary embolism, Medsafe put out a warning. The number of deaths was small, but there was a safer alternative.

The number who regret transition and have been harmed may also be small; it is still too early to know for this new group. Earlier studies showed reassuringly low rates of regret, but were mainly of short duration or with high losses to follow-up. Recent findings on discontinuation from sex hormone treatments are higher: in the order of 20 per cent at five years, though not all those will have discontinued because of regret. Is there a safer alternative? Yes, the route Sweden and England are taking is to offer psychological support, not hormones, except in rare cases. Individualised psychosocial interventions as first-line treatment is also recommended by the Australian National Association of Practising Psychiatrists.

This sounds reasonable, but in New Zealand the current portrayal of gender affirming health care has caught us all in a terrible trap.

New local information sheets for parents and children make the strong claim that puberty blockers improve mental health, lower depression and suicidal ideation and improve quality of life for gender dysphoric children. They also assert that “puberty blockers are as safe as other routine medical care”; “side effects of puberty blockers are very rare in the short term”, lead to “no significant change in bone density”; and “taking blockers does not influence the choice to subsequently take hormones” (and cite one study that does not prove this). Nevertheless, “All medicines have risks and benefits. Qualified health professionals explain these risks and benefits to transgender young people and their whānau or family, to ensure informed consent.” In other words, it’s up to the child and their family to decide.

Who are these children who may be eligible for treatment? “[A]nyone whose gender is different than the gender they were assigned at birth. This is intended to include takatāpui, non-binary, and gender fluid people, alongside anyone who seeks gender-affirming care to express their gender, however they might choose to identify.” These information sheets were produced with the assistance of the Marsden Fund.

Why do I think this is a terrible and tragic trap?

First, we are teaching children in school that biological sex is not binary, they were assigned their sex at birth, they have a “gender identity” — an inner sense of being male or female — they might have been born in the wrong body, and they can change sex. As a consequence, among the longitudinal study Growing Up in New Zealand cohort, aged 12, 8 per cent of children who were born girls now report seeing themselves as transgender or gender diverse: “a boy, mostly a boy, or somewhere in the middle”, and 1.5% of those born boys reported the converse. At its simplest, this is an extension of what we know: that girls have always been more likely to have gender atypical behaviour than boys.

What is new is the literal-mindedness. A clinician at the Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) in London surmised that because they were dealing with young people who had “a deeply entrenched and concrete solution to a problem” this got reflected in the practice of the clinicians themselves. We have taught these girls to think they are really boys and thus to be disturbed by the changes of puberty towards being a woman — or more disturbed than most girls feel. The only solution looks to be suppressing puberty. We adults have encouraged children to think like this.

Second, in New Zealand easy access to puberty blocking hormones is portrayed as the solution to their gender dysphoria and their concerns about puberty. Though the 2018 New Zealand guidelines recommend puberty suppression for children with “persistent and well documented gender dysphoria”, the information sheets noted above show a move to put decision making in the hands of the child and family, rather than being based on a formal diagnosis. This is called a consent-based approach. Clinicians help the child and family decide on the use of puberty blockers; they reassure them blockers are harmless, will have no effect on whether the child goes on to take cross- sex hormones and will definitely make the child feel better and less suicidal.

Third, some parents come to the clinician with different information. These parents know they are not being provided with balanced information. They know they should be told that only a small minority of children who experienced gender dysphoria in the past persisted in their dysphoria as they grew up; most reconciled with their birth sex. They also know that now more than 90 per cent of children who are given puberty blockers go on to take cross-sex hormones. They realise that is a worrying puzzle: why do so many continue with gender dysphoria now but not in the past? Is it an effect on the brain of the the hormone therapy itself, as Cass has suggested? Or is it because children are affirmed in their trans identity nowadays, instead of in the past when clinicians adopted a neutral stance or actively worked with children and their parents to lessen gender dysphoria?

These parents are familiar with the new views of gender identity among New Zealand clinicians who advocate gender-affirming care. Those clinicians no longer say that children can be born in the wrong body and know for sure about their gender. Instead they now say (in the guidelines for adults in primary care): “affirming one’s gender is not necessarily a linear process but takes place over a lifetime”. The parents know that if gender is fluid and can keep changing it is usually wrong to take even partly irreversible steps to fix it.

Parents may also have read the systematic reviews of the benefits and harms of puberty blockers, from the UK and Sweden. The latest, 2023, from Sweden concluded: “the long-term effects of hormone therapy on psychosocial health are unknown”, and such therapy “delays bone maturation and gain in bone mineral density”. The reviewers warned that such treatment in children with gender dysphoria should be considered experimental. Parents may also have heard that, at least for boys, puberty blockers impair genital development and hence sexual function if they proceed to cross-sex hormones; in this case infertility is likely for both sexes.

As a consequence of these premises, the parents and the child are in a terrible trap. The child is encouraged by the information provided by the gender clinic that her health will be transformed by blockers. Parents want their child to be happy. The child may even feel better without sex hormones in her body. Perhaps the clinicians see this, and feel justified in putting their own experience before the scientific evidence.

Informed parents know this is a dangerous path. They know that the information they have been given is seriously unbalanced. Yet, how can they disagree with their daughter without gravely endangering their parental relationship?

Photo: Shutterstock

It will be possible to undo this terrible bind if health authorities take the lead. Mental health clinicians working at the GIDS in London made complaints that led eventually to the Cass review. Many clinicians in New Zealand have contacted health authorities to voice their concerns; more should do so. Parents and people who regret youth transition are able to take complaints to the HDC; the Commissioner should be prepared to investigate them. The Medical Council should also uphold its standards for the profession.

Medsafe, the medicines regulator, is responsible for monitoring the safety of medicines and receives notifications of adverse effects. Every person who regrets medical transition (or their doctor) can notify this confidentially as an adverse effect to Medsafe (via the Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring — pophealth.my.site.com/ carmreportnz).

The role of the Ministry of Health is to provide coherent leadership across the health system. It should be the agency to take a lead in commissioning an independent review. It is time for action.

Charlotte Paul is an epidemiologist and emeritus professor in the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine at the University of Otago.

This article appeared in the December 2023 issue of North & South.