A state of denial

The coalition government is scrapping a commitment to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi in child-welfare legislation, but the past will not be erased. As Aaron Smale reports, history has been tragically repeated in the state’s failed approach to Māori children in its care.

By Aaron Smale

A couple from Bay of Plenty turned up at the hospital in Lower Hutt after milking the cows then driving seven hours. As they sat in a waiting room, a nurse walked up to them with an infant wrapped in a blanket, handed him over and walked away. Neither of the couple had had anything to do with a newborn before.

After a few minutes the nurse returned. “Well do you want him or not?” Stunned and unsure, the couple said yes. Shortly afterwards, they walked out of the hospital carrying someone else’s child and began the long drive home.

That’s how it was done in 1971. Social Welfare was probably just glad to get rid of the child — Māori boys were the hardest to place for adoption. The basis for this transaction was the Adoption Act 1955. And buried in that Act — which is still on the books and still being used — was a section that runs like a dark thread through New Zealand’s history of land alienation and the alienation of children from their own history and genetic and whānau heritage.

The government thinks it will try and erase that history, but will simply be repeating it. In the coalition arrangement between National and ACT was a little noticed clause that may come back to bite those who wrote it. The two parties promised to: “remove Section 7AA from the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989”. That section says that duties of the organisation’s chief executive recognise and provide a practical commitment to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (te Tiriti o Waitangi).”

The chief executive must ensure that: “the policies and practices of the department that impact on the well-being of children and young persons have the objective of reducing disparities by setting measurable outcomes for Māori children and young persons who come to the attention of the department,” and that, “the policies, practices, and services of the department have regard to mana tamaiti (tamariki) and the whakapapa of Māori children and young persons and the whanaungatanga responsibilities of their whānau, hapū, and iwi.”

According to National and ACT, these things can be done away with at the stroke of a pen. But the government will find out one way or another that it’s not quite so easy. Māori have been ignored before. It never goes well.

Section 7aa of the Oranga Tamariki Act was introduced in July 2019. Whether it was a kneejerk reaction or was already in the pipeline, it was less than a month after the issue of Māori children being taken from their whānau blew up in the media in spectacular fashion, after the attempted uplift by Oranga Tamariki of a seven-day-old baby from its mother in Hawke’s Bay Hospital. The Labour government tried to deny what was plain for everyone to see — that the state was acting like a thug. Inquiries ensued, policies were (supposedly) changed and the government went into major damage control. The latest government’s scrubbing of a section of legislation won’t erase the issues that gave rise to that outcry.

Journalist Melanie Reid’s story on the Newsroom site about the Hawkes Bay Hospital case led to half a dozen official inquiries and a lot of outrage from New Zealanders who couldn’t comprehend government agencies and hospital staff putting immense coercive pressure on a mother and her whānau to remove a newborn child within hours of its birth.

The baby would escape the clutches of Oranga Tamariki, but what bothered me was the ones who had been taken. Where were they? And what was this bizarre process that they were going through? It seemed to me that these children were like ticking human time-bombs. One day they would find out the truth about their origins and the circumstances surrounding their removal from their family and their whole world would blow up in their faces.

Reid had called me about the story because I’d done a fair bit of work on the removal of children by the state in the 1960s, 70s and 80s — children who ended up in abusive institutions such as Kohitere and Lake Alice.

Her use of the term “permanent placement” caught my attention. “What is that?” I asked. It sounds like adoption. “No, they never use the word adoption.”

They can’t. The authorities avoid the word adoption because it involves a totally different legal process for children being placed with non-kin caregivers. But “placements” do become permanent and for all intents and purposes have the same outcomes as adoption. It happens within a dubious legal framework bringing traumatic outcomes for the birth parents, uncertainty for permanent foster parents and yet to be discovered consequences for the children themselves.

These children — it’s unclear how many — go through a process created through political bluster, bad law and policy that ignores previous failures of the state in its intervention in the lives of children.

When he became Minister for Children in 2020, Labour’s Kelvin Davis set up a Oranga Tamariki Ministerial Advisory Board. Sir Mark Solomon, who became chair of that board in 2022, had heard conflicting stories about the numbers of children ending up in permanent placements and also rumours of children ending up overseas. So he asked Oranga Tamariki for numbers on both issues. “In my first meeting with the Oranga Tamariki I did put the question: how many children have been adopted out, how many have been adopted offshore?” Solomon told North & South. “We cannot get an answer from them. The only answer was, there’s been none under Oranga Tamariki.” Solomon is aware of anecdotal accounts of a large number of children being affected. “But we can’t get any response.”

Above: Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre in Levin.

Oranga Tamariki came into being in 2017, as a renamed Child, Youth and Family Service (CYFS) department. Many of the changes around that time were made in response to the Rebstock Report, written by consultant Dame Paula Rebstock. One of the risks identified in her report was what to do with young children in the custody of the state bouncing from one placement to another.

Important earlier changes happened back in 2010, when then Minister of Social Development Paula Bennett announced a new “Home for Life” policy. Aimed at the 5000 children then in state care, that policy created a raft of unintended consequences that are still playing out for all involved.

The language around the policy announced by Bennett was more marketing than law. Permanent placements have been variously branded as “Home for Life” or “permanent guardianship”. A Cabinet paper even proposed a policy launch with all the trappings of a celebrity bash to be held at the Beehive in late 2010. The proposed “Brighter Futures” soiree was for a policy that, according to the communications strategy, was about finding safe, secure homes for children who didn’t have one. In the end, the event didn’t happen; a media release went out instead. And little comment was raised at the time. Children’s advocates have admitted they were too distracted by other family-related law changes to realise the implications of changes in guardianship practices under Home for Life.

The policy naively overlooked or downplayed some potential long-term consequences — consequences such as children losing all contact with their birth families. It has run alongside ongoing reviews of adoption law without any serious integration of the two strands. There are also suggestions — most notably in the raft of reports that were written about the attempted removal of the child in Hawke’s Bay — that how it has been applied in some cases is in breach of domestic and international law.

These children — it’s unclear how many — go through a process created through political bluster, bad law and policy that ignores previous failures of the state in its intervention in the lives of children.

National’s stated intentions were yet another political response to the ongoing social dilemma of how children from disadvantaged or abusive backgrounds should be viewed and what the state’s role should be in their lives. The questions and the various answers are as old as the nation itself, and were inherited from Britain or borrowed from other western countries. From baby-farming in the 19th century to closed adoption in the 20th, the state’s interventions have created unintended consequences for children that have followed them into adulthood.

In the last 50-odd years those consequences have increasingly fallen on Māori children, resulting in trauma that ripples across generations. And Māori, including those who were adopted in an earlier era, are raising objections to what they see as the latest attack on the integrity of the whānau and the rights of Māori children to know who they are.

More than a dozen years on from its launch, legal critics, parents and social workers continue to have deep concerns about Home for Life, telling North & South there are long term implications for Māori children in particular, including the severing of connections with iwi and hapū, leaving a vacuum where their identity should be.

Image: Judge Tania Williams has worked with iwi leaders and local communities in an effort to increase knowledge and awareness of Family Court and Oranga Tamariki procedures.

The policy, Bennett said in her media statement, was about “removing the obstacles” to taking a child on permanently and giving them a better life. It would allow the more than 2000 foster carers in the system to offer a child permanency. “But it’s open to any New Zealander who is considering welcoming a child into their home.”

The statement made no mention of birth families or the ramifications of the removal for a child later in life.

The Home for Life policy tried to address the issue of children in care “drifting” through multiple foster placements without a long-term plan. A Ministry of Social Development report Bennett received in 2011 said: “Child, Youth and Family brings children into care to ensure their safety and wellbeing when they are living in high-risk and unsafe situations. However, we must ensure they are only in our care for as long as is necessary until we can find them a permanent home, either with their own family, with extended whānau, or a new family they can call their own.”

One of the issues that the policy was trying to address was where caregivers and birth parents could not agree on basic arrangements like access, choice of schooling, or medical treatment. Special-guardianship changes were designed to give caregivers stronger decision-making powers, but in doing so effectively reduced the involvement of birth parents and, at times, excluded them both legally and practically.

While the legal framework and stated purposes were for fostering arrangements, the effect for the child was the same as adoption — they were removed from their birth parents and placed with strangers in a permanent parenting arrangement.

But the status of the child in terms of its relationship with both its birth parents and caregivers under Home for Life is both less certain and more complicated than what it is for those adopted under the Adoption Act.

Rotorua-based lawyer Tania Williams (a District Court Judge as of March 2023), who represents children in the Family Court, was among those caught out by changes to the system. She says around the time of the Rebstock report, lawyers were focused on changes to the Family Court system and missed changes that were being made to the definitions of guardianship.

Use of the term “special guardianship” has flown under the radar of not just lawyers but also adoption experts. Researchers, lawyers and other child advocates have struggled to pin down what is happening to children not just in Oranga Tamariki’s legal custody but what is happening to them when they are transferred into foster homes. While the state can retain custody under a fostering framework, it has been shifting custody under different legal arrangements.

This shift is creating ramifications that legal experts and child advocates say has potentially life-long negative implications. And we don’t know how many children it is happening to.

Sir Mark Solomon is not the only one who has had difficulty getting answers on numbers. North & South has obtained documents and information from numerous sources including academic researchers, government agencies including the Waitangi Tribunal, and OIA requests and responses to parliamentary written questions particularly those asked by Act’s Karen Chhour — who is now the Minister for Children. The numbers are impossible to reconcile.

One number North & South was able to establish was of children under 18 ending up in permanent placements — there were 430 in 2011 and 489 in 2012. By 2016 there were 405, with 340 in 2017. But dive into the details and things get murkier, particularly when trying to identify how many are in the custody of what are referred to as section-396 providers — non-government organisations, whose role comes under section 396 of the Oranga Tamariki Act, who effectively operate as subsidiaries of Oranga Tamariki — where the children end up if they are put into permanent placements.

When researcher Emily Keddel from Otago University made an OIA request asking how many children were in the custody of section-396 providers, Oranga Tamariki responded that: “Our case-management system does not hold information on all children who are in the custody of s396 providers. This is because we have not been required to capture information about children in the custody of s396 providers. The NGOs are not small operations. One of the main organisations, Open Home Foundation, has 121 contracts with the government; it received $21.8 million in taxpayer funding in the 2019 financial year and $18.6 million in 2018. Open Home Foundation also has access to Oranga Tamariki’s computer system, CYRAS, which tracks children and families on its books. By way of comparison, the Children’s Commissioner has only “read” access to CYRAS; Open Home Foundation has read and write access for the permanency workers who find caregivers for children. No other organisation has this level of access.

When Davis was asked by Chhour how many children were in the custody of Open Home Foundation, he provided a chart that showed more than 100 children were in the organisation’s custody each year since 2017, apart from 2021 where the number was 92. The highest number was 145 in 2019. It is understood that the numbers of children in the custody of other NGOs is in the single figures.

Legal critics, parents and social workers continue to have deep concerns about Home for Life, including the severing of connections with iwi and hapū, leaving a vacuum where their identity should be.

Despite the tight integration, Oranga Tamariki cannot answer basic questions about the operations of these NGOs. Davis was asked by Chhour: “How many placements of children into Permanent Care over the past five years, if any, were overseen/processed by NGOs?” Davis replied: “I have been advised by Oranga Tamariki that the requested information is not readily available as it is not centrally recorded in our system” It is also unclear whether children who end up in permanent placements might end up overseas. Davis was asked by Chhour how many permanent placements are with people who are not New Zealand citizens. “I am advised by Oranga Tamariki that in their legacy system, residency status was not a requirement, and therefore not recorded,” Davis replied. “Since residency status has been captured under a system introduced in June 2022, no permanent caregivers had been approved who were not citizens or permanent residents of New Zealand.” Asked if there were any rules around children being placed in permanent care being taken overseas permanently by guardians, Davis replied: “I am advised by Oranga Tamariki… that once they have discharged tamariki from their custody and guardianship, Oranga Tamariki does not have any say over the decisions made to move tamariki overseas. These decisions are made by their permanent caregivers.”

Opening the doors to homes for life

Former social worker Kerri Cleaver was working in Child Youth and Family Services in Dunedin in 2011 when a staffer from an NGO arrived to work out of the same office. That in itself was not so unusual: the NGO had worked with CYFS for some time, and had been training CYFS social workers. But it rang alarm bells for Cleaver when the NGO staffer was assigned to permanent placements. “They gave that worker all of the cases that they had decided to push through to permanency and that was the start of that Home for Life legislation.”

Cleaver, who is now a lecturer in the University of Canterbury’s social work department, says from what she has observed, Oranga Tamariki’s focus in recent years is about getting children off its books and saving money, while doing little to support the families they are removing children from. “Some of this is driven through this practice idea that came into being years and years ago around the idea that permanency is required very quickly for children,” she says. “You have to make decisions fast, particularly if they’re really young. You’ve got to set them up in permanency. You don’t want to give parents extended periods of time to sort themselves out. None of those child protection services for the last couple of decades have given any resourcing to support parents.”

Cleaver left CYFs to set up a programme with Kai Tahu — Tiaki Taoka (Caring for Treasures), which is designed to support whānau to bring up their mokopuna as Kai Tahu. She later held roles at the Children’s Commission. She gave evidence at the 2020 Waitangi Tribunal inquiry into Oranga Tamariki, describing what she was seeing in Oranga Tamariki as “child trafficking”.

She stands by that assertion today. “Oranga Tamariki were really happy to move babies into what they thought were the right homes without doing the work with whānau first. So really clearly to me, that was baby trafficking that was going on.”

She says the lines are blurred between adoption and permanent placements — one goes through a consent process while the other doesn’t. Those who lose their children to Oranga Tamariki are often overridden in the process. Cleaver says adoption-services staff are often the same people looking for caregivers. “You’ve got a whole lot of people that are signed up to adopt, they’ve been waiting years and then they’re offered children under the Child Youth and Family Act or Oranga Tamariki Act.”

The Chief Executive of social-support organisation Te Iwi o Ngati Kahu Trust, Dee-Ann Wolferstan, also believes Oranga Tamariki has been driven by the imperative to get children off its books and that NGOs like Open Home Foundation are part of that process. She says Oranga Tamariki is cutting across not only Māori whānau but Māori iwi and organisations that are trying to keep Māori children with their whānau. “Oranga Tamariki’s role was to reduce what we call drift children, children that have been in care over two years.” She says Bennett and her successor as Minister, Anne Tolley, both had a focus on reducing the number of children in that position.

And Wolferstan says some whānau are so disconnected that they name anyone as whānau to satisfy Oranga Tamariki when a permanent home is being sought. “They’ll say, ‘Oh, well, 80 per cent of the children are with whānau’. You can ask for all the data you want, but I can tell you now that data is not real.” She is critical of where resources are targeted. “There is low, low investment into keeping children with the whānau.” By contrast, she says, a lot of funding goes to permanent caregivers who are not kin to the children and who often hand children back if they run into problems.

Wolferstan believes funding is another reason for permanent placements being preferred to adoption. She says under Home for Life, an original contract gave a foster family $5000 up front to take on a child, then a weekly payment of the unsupported child benefit until a child was 17 or 18. “If they do adoption, you are entitled to zero.” As an example of how things can be done differently, she says her organisation supported a large whānau to regain custody of children, with an aunt paid to support the whānau after school. “Those children are back with their parents and doing really well. The eldest started nursing school, and this is only in the last year. So there are these pockets of goodness, where they’ve gone outside the square and just let people do natural things with families like we did.”

Cleaver says it doesn’t matter what terminology and legal framework is used to relocate Māori children, the impact will likely be the same for those children as they grow up and discover they have an identity that is different from their foster or adoptive parents. It continues to happen here and it continues to happen to indigenous children in other countries like Canada and Australia.

“There’s no protection that occurs within that permanency and Care of Children Act legislation that protects a child’s right to their identity and their culture. That’s why it is really just a different version of adoption. Those caregivers that are caring for that child can tell whatever story they like, and that child is not going to be any more in the know. They’re reliant on those parents to tell them the truth and that’s often not the reality.”

Above: Kerri Cleaver left Child Youth and Family Services to set up a programme designed to support whānau to bring up their mokopuna as Kai Tahu.

The fraught history of adoption

Scrapping Section 7aa is a political stunt to prove to a Pākehā electorate that there’s one law for all. But the Crown has treated Māori children differently from the start and usually not to their benefit. The scrubbing of a few words from one statute will not so easily erase the history behind it or the legal implications that have been the subject of significant court judgements. Nor will it expunge the history of removing indigenous children that is part and parcel of colonisation.

Two pieces of seemingly unrelated legislation nearly half a century apart underline that you can’t separate the law around child welfare from the Treaty of Waitangi — the Native Lands Act 1909 and the Adoption Act 1955.

Māori land legislation is a convoluted mess, and has provided some of the most damaging legal weapons the Crown has deployed against Māori. And one of them, the Crown’s individualisation of Māori land title, was not simply an issue to do with land tenure. It was a fundamental restructuring of Māori society. In the long run, it raised questions about the status of children. If land titles became individual, who were those titles passed on to? If a Māori child was adopted under customary practice, who did the child inherit land from? Their whangai parents or their biological parents? Or both? The Crown considered this too untidy for its liking and meddled further.

The Crown’s assumption of a nuclear family did not fit with how Māori children were regarded in Māori society. Children did not belong to just the couple who had conceived them. Māori children were often raised by relatives other than their biological parents, including grandparents and wider whānau members. The reasons varied — in many cases an eldest child was brought up by grandparents to pass on cultural knowledge; in others a couple that couldn’t have children were gifted a child; or children were taken in by extended whānau to relieve an economic burden. One of the Māori terms that is sometimes translated as adoption is whangai, which literally means to nurture or feed.

Section 9 in the Native Lands Act 1909 states baldly that Māori traditional adoptions would no longer be recognised, declaring “No adoption in accordance with Native custom, whether made before or after the commencement of this Act, shall be of any force or effect, whether in respect of intestate succession to Native land or otherwise.” The outcome of this legislation was mixed. For many remote Māori communities it was simply ignored. But the wording in this section of the legislation was revived when the Adoption Act 1955 was passed and the Native Lands Act 1909 was specifically referenced. The Adoption Act states that: “No person shall hereafter be capable or be deemed at any time since the commencement of the Native Land Act 1909 to have been capable of adopting any child in accordance with Māori custom…”

So, if the Native Lands Act of 1909 had unsuccessfully tried to abolish Māori customary adoptions, the Adoption Act 1955 had another go. It is worth noting that the Adoption Act was passed at a time when Māori urbanisation was in full swing and Māori had already lost most of their land. The issue of succession was almost a moot point. Māori social structures were again being fractured by rapid urbanisation, and at a time when the Māori population was exploding — doubling in the 25 years to 1961. The Crown saw urbanisation as a chance to carry out the last stage of assimilation by scattering Māori throughout Pākehā society so they’d learn to behave like Pākehā in their economic and social interactions. The intention of the Adoption Act was the same as it had been for a raft of previous legislation relating to Māori — assimilate Māori and erase their property rights, their language, their culture and their social and family structures. In other words, erase Māori as a distinct people.

Easier said than done.

The clause in the Adoption Act abolished what had been the one of the main options for raising Māori children. More broadly the Act legally severed an adopted child’s relationship with their biological family, which for Māori children is catastrophic in terms of connection to their wider identity and even rights to land. Like the legislation around Māori land, the Adoption Act and other statutes around child welfare have assumed that children can be individualised.

This point was made by Tuhoe leader and social worker John Rangihau in the landmark 1986 report, Te Puao-te-Ata-tu. “At the heart of the issue is a profound misunderstanding or ignorance of the place of the child in Māori society and its relationship with whānau, hapū, iwi structures,” the report said.

In a 1997 High Court decision, the Court considered the organisation of Māori whānau was so fundamental to Māori society, it was impossible to view it apart from obligations under the Treaty: “…all Acts dealing with the status, future and control of children are to be interpreted as coloured by the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi”.

In other words, you can scrub treaty principles from legislation but the court will have to consider them anyway if they are directly relevant to the issue at hand. And the court said there can be nothing so relevant to Treaty principles than the place of a Māori child.

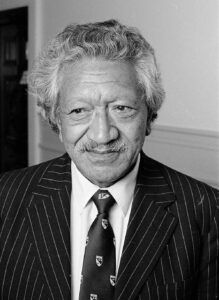

Image: Tuhoe leader and social worker John Rangihau.

The permanency policy that has emerged since adoption dwindled tries to step around the Adoption Act, but ends up creating its own problems in relation to Māori children. It combines two different but parallel statutes to create a hybrid outcome that is akin to adoption. New Zealand’s adoption legislation, which has remained largely unchanged since the 1950s, is now rarely used — it peaked into the late 60s and early 70s when thousands of children were adopted. The fading of the stigma of single motherhood, combined with easier access to contraceptives and abortion has seen the numbers of babies available for adoption dwindle.

Many of those who have applied to adopt have been offered the option of special guardianship, without always understanding the implications. The special guardianship orders that place children with foster parents permanently use provisions in the Oranga Tamariki Act that overlap with and refer to the Care of Children Act (COCA). The former is about care and protection of children who are at risk of neglect or abuse, whereas COCA was designed for resolving private disputes between former couples negotiating custody access. In some cases court orders under COCA grant custody exclusively to one parent, without completely extinguishing the role of the other parent but suspending or curtailing their everyday rights and access.

Various forms of guardianship can be combined depending on circumstances and court decisions. The most basic is the existing guardian, which is initially assumed to be the birth parents, though when Oranga Tamariki removes a child from the birth parents, the custody is transferred to the state. The parental rights of the birth parents are very rarely completely extinguished although they can be suspended, sometimes indefinitely. Sole guardians or additional guardians can be appointed and arrangements made for contact between children and their birth parents in such arrangements, although conditions can be stringent. Special guardianship is something else. It stops short of legally extinguishing parental rights, which adoption does, but is harsher than other options.

The Crown has treated Māori children differently from the start and usually not to their benefit. The scrubbing of a few words from one statute will not so easily erase the history behind it…

Family law expert Mark Henaghan of the University of Auckland says while adoption and special guardianship occur under different legislation, the practical outcome is virtually the same. “Adoption is really a transfer of guardianship,” he says. “That’s why it’s called the king hit of family law — it transfers guardianship… It totally cuts the birth parents. A special guardianship order doesn’t totally cut the birth parents, but it has exactly the same effect.”

Tania Williams believes the changes to guardianship was influenced by law in the UK, where special guardianship and adoption are tightly linked. She says New Zealand went all-in on special guardianship because adoption was a hard sell politically. In many respects, special guardianship has become a de facto adoption.

Permanent placements under special guardianship legislation have had several name changes since being dubbed Home for Life under Bennett, but remains a severe legal step, says Henaghan, excluding the birth parents and giving a special guardianship that lasts until the child is 18. “That’s what happens in adoption,” he says. “So it’s a massive, massive step.”

Williams agrees. She says access arrangements made initially under special guardianship have sometimes limited contact to four hour-long visits a year. “Nobody can maintain a relationship with anyone, let alone a baby, on one hour, four times a year. So the impact was you would disconnect.” She says many birth parents find the whole process so discouraging and crushing, they give up. “By the time it gets to those final orders, whānau have given up. Whether they’re Māori or Pākehā, they’ve given up because our system is quite hard on them.”

A child can be placed in care or have their orders continued for another year based on a five minute interaction in court, Williams says, without whānau really having a say. “Why would you turn up when someone treats you disrespectfully by not even acknowledging you, or not giving you the opportunity to talk, or you say a couple of things, and nobody listens. So whānau will give up. By the time you get to those final orders, nobody is there except the lawyer for child and the caregivers, their lawyer and Oranga Tamariki. That’s just wrong.”

It has the same effect as adoption, she says. “If your rights are suspended, and you have minimal access, if you have any, after a couple of years that will drop off.”

With people hoping to adopt often being offered the Home for Life/special guardianship option, “challenges” arose, officials acknowledged in a briefing for Tolley when she took over from Bennett in 2014, “notably where parents do not cease to express interest in contact with or wanting to resume the care of their children”. Proposed Home for Life carers could be caught in a process over which they had little control, Tolley was told. But the briefing makes no mention of the difficulty faced by birth parents who have even less control — and have endured the trauma of losing their children.

Annabel Ahuriri-Driscoll, who did her PhD on people like herself who are Māori but were adopted by Pākehā, believes children who are permanent placements could end up facing similar loss of identity as those who were adopted in an earlier era. Adopted during the heyday of the practice, Ahuriri-Driscoll had a good relationship with her adoptive parents but like many of the subjects of her research she struggled with the alienation of not knowing who she was and being disconnected from her Māori identity. She believes children put in permanent placements are at risk of getting a distorted and negative narrative about their origins, which can play havoc with their mental health as they grow up. “Something that worries me for these children is that their voices are not being heard, and their experience not being recognized. And the rhetoric of the Home for Life policy, like the rhetoric around adoption, glosses over loss, it glosses over trauma. As well as being disconnected, your actual experience is negated.”

Ahuriri-Driscoll was dismayed when she read a paper from Oranga Tamariki that discussed the impacts of adoption and fostering without reference to some major New Zealand-based research. The experience of adoptees, particularly Māori adoptees, seemed to have been missed altogether. “I don’t have confidence that people really understand what those children will go through, and the kinds of supports that they will need.”

Tania Williams says Family Court judges bear a lot of responsibility for letting government policy roll through the courts with very little questioning. In the numerous inquiries that followed the exposure of the case in Hawke’s Bay it was found that court decisions were being made on the basis of evidence from Oranga Tamariki social workers that was outdated or dubious. “At what point did the Family Court ever say, ‘Slow down. Stop. Have you thought about…’? Until the attempted uplift in Kahungunu, they were not even mindful.”

She says the same profound misunderstanding identified in Te Puao-te-Ata-tu in 1986 has led to thousands of Māori children going into care. “Everyone’s pointing the finger at Oranga Tamariki, but the Family Courts sits on the side saying, ‘Nothing to see here, folks, it’s over there.’”

Mark Henaghan says the legal profession, including the courts, bear a large responsibility for the harm occurring in the child-welfare system. “Professionals come charging in, thinking they know everything and do more harm than good.”

Besides her legal work representing children in the Family Court, Williams also sits on the Parole Board. She sees children being taken from their parents and given to strangers in the Family Court with the birth family completely excluded. But she also sees adults coming out of the prison system who have been through welfare and have no one — neither birth parents or foster parents — at the hearings to support them. “The care-to-prison pipeline is still there. Māori offenders are appearing who are disconnected.” These people have nowhere to go. “With whānau — good, bad or indifferent — if things go wrong, you go home. Things may not be crash-hot at home, but you go home. And you lay low for a little bit… but many of these young people, they haven’t got that.” Government says it wants to strengthen communities, she says. “But actually, they don’t.”

These issues are not unique to New Zealand. In former colonies — New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the United States — the removal of indigenous children is a common dark chapter of history. The adoption of indigenous children by non-indigenous people became a flashpoint in the United States in the 1960s and 70s, leading to the Indian Children’s Welfare Act, passed by Congress in 1978, which prioritised the retention of indigenous children within their wider kinship networks. The United States, with one of the longest and ugliest histories of colonisation, has recognised in Federal law, upheld by the Supreme Court, that indigenous children deserve legal protection from the state that is separate from other welfare legislation. Under the government elected last year, New Zealand does not.

Section 7aa merely expanded the definition of the best interests of the child to not only include care and protection but also acknowledge something hard to articulate in legislation — that a child’s right to know who they are, where they are from and who they are part of is fundamental importance to a person’s well-being.

The child who was picked up from the hospital in Lower Hutt in 1971 was me. I was adopted by a Pākehā couple; my birth mother is Pākehā, while my birth father is Māori. I can personally attest to the loss of identity that was implicit in the closed adoption practice of that period, carried out under a social policy that cloaked a child’s origins in shame and secrecy. While I benefited from finding out my Pākehā heritage, my discovery of my Māori heritage has been quite a different experience, with many more layers and wider relationships of belonging.

While I had a childhood with all the appearances of normalcy and security, the basis of my identity was stripped the moment I was carried out of that hospital and the final adoption order was signed six months later. I have spent the rest of my life trying to get it back. I’m still not there. I don’t know if I can ever recover it fully. My adoptive father once said to me, “You shouldn’t have been taken from your family”. He wasn’t saying he didn’t want me, or my sister who is adopted. He was merely bearing witness to the damage adoption had caused for both of us. For that honesty I was grateful and relieved.

The erasure of section 7aa has no practical impact on me personally. But it speaks volumes about how this government regards the damage that was caused to me and thousands of others by being cut off from our whakapapa and the relationships and identity inherent in those relationships. The erasure of section 7aa is a denial of the damage the state has done over generations with its intervention in whānau and through Māori being shut out of decisions about their own descendants. Where the United States, Canada and Australia can face their failures regarding indigenous children, New Zealand continues to deny them. We don’t even keep count of how many have been taken and never given back.

I’ve reported for more than seven years on the damage done to tens of thousands of Māori children who were removed from their whānau by the state on the pretence of giving them a better life. That supposedly better life included the torture and rape of children, the infliction of violence and solitary confinement. I live in Levin, where the institutions of Hokio Beach School and Kohitere were among the worst at instilling trauma in generations of Māori and cutting them off from the whānau and wider networks that might have created a different future. For many, those institutions were the start of their pathway into prisons and gangs. I know many who walked that path and are still being punished for how that childhood trauma has manifested in their adult lives.

The state has no moral high-ground to stand on. It is the worst parent any child could have. The erasure of section 7aa from the legislation does not erase that history. It simply denies it.

Aaron Smale is North & South’s Māori Issues Editor, a role supported by NZ on Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund.

This story appeared in the February 2024 issue of North & South.