Great Expectations

New Zealand’s future workforce is going to increasingly be brown. But is our education system stuck in a past of low expectations for Maori students that threatens the country’s future prosperity? Aaron Smale reports, in part one of a three part series.

By Aaron Smale

It was still dark on the platform at the train station in Levin when the Capital Connection rumbled in. The train was still relatively empty so it wasn’t hard to find a seat with a table. At Otaki, a bunch of passengers climbed on and a group of Maori women sat next to me.

I can’t remember what kicked off the conversation but I ended up talking to the wahine

next to me, Maraea Hunia, who was working at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research. She now works at Tatai Aho Rau Core Education, a non-profit NGO that works in education.

At some point, I mentioned I’d attended St Stephens School, the famed boarding school for Maori boys. Like all old boys, I knew the myths and the violence. One legacy is its public image as a conveyer-belt of Maori leaders, but there is also the less celebrated reputation, what one Education Review Office report characterised as an atmosphere of violence, that led to a dwindling roll and eventual closure in the late 1990s. I’d left down its long, tree-lined driveway in 1987, relieved to be escaping the random acts of violence that could strike at any moment, day or night. They might not happen that often, but it was the constant threat that wore you down.

St Stephens was only matched — or perhaps surpassed, depending who you’re talking to — by Te Aute College in Hawke’s Bay, the alma mater of Sir Apirana Ngata, Sir Maui Pomare and Te Rangi Hiroa. I recall a haka we performed at St Stephens that referenced Ngata. He was quoted more than once by speakers at prizegivings.

When I discovered, on meeting my birth father, that I was Ngati Porou, I started tapping into the history of that iwi. Ngata is revered on the East Coast and he was born in Te Araroa where my great-grandmother grew up. She was roughly contemporary with Ngata, so would probably have known him or at least his whanau. My great- grandfather grew up in Tikitiki, virtually across the Waiapu River from Ngata’s adult home in Waiomatatini.

So I thought I knew about Maori boarding schools. And in my Ngati Porou arrogance I’d assumed Ngata’s exemplary success was due to something special about us as an iwi. That was until Maraea Hunia schooled me in another aspect of Maori boarding school history I had no idea about.

“John Thornton [an early headmaster of Te Aute College] saw the potential of the students, so he set about educating them so that they would matriculate,” she told me. “And they did. The first one was Ngata and then there were a bunch of them […] The government didn’t like it because it wasn’t part of their colonizing mission. Their mission was to create a slave labor force. So they said stop.”

By the time I got off the train in Wellington I was reeling — there should have been hundreds of Apirana Ngatas, not just one. What position would Maori be in today if that gate had not been shut? If other students like Ngata were given the chance to not only reach their potential but to take back that education to their communities throughout the country? While Ngata was an exceptional individual, he was also just the one that slipped through the barriers that were erected for others who werenjust as talented.

If other students like Ngata were given the chance to not only reach their potential but to take back that education to their communities throughout the country?

The stories of Maori children being beaten for speaking their first language are well known,but it wasn’t only their language that was taken. They were also robbed of their academic potential. It was official policy from the start. The education policy of New Zealand has deliberately organised New Zealand’s society and economy, always placing Maori at the bottom.

Through personal and professional conversations over decades, I’ve seen and heard the trauma the education system has inflicted on generations of whanau, including my own. In Hunia’s case — and mine — you only have to go back one generation to find that trauma. And it didn’t stay there.

“My dad’s family, they all spoke te reo down to my dad. But then the two younger ones didn’t really speak.

“They were hit with a manuka stick, five- year-olds, with a manuka stick at school. That’s what Dad said. The teacher, a woman, hit them with a manuka stick every time, and … when they tried to speak English, she would hit them for that as well for not getting it right.” The children were stumped. “They didn’t know what to say, they didn’t know what language to speak. Some of them just retreated and didn’t say anything. And some of them put themselves forward and just got continually bashed.”

I have two generations of whanau that got hit. One family member has panic attacks when she hears Maori spoken by fluent speakers. She also had her Maori name legally stripped when she became an adult. I’ve heard stories from others of their parents being thrashed with horse whips. In one case a girl was thrashed with a bike chain that got embedded in her ankle.

While the physical violence Maori children suffered was horrific, what damage was done psychologically over generations? One impact is the negative self-image it left generations of Maori with. After reporting on the state’s abuse of children in its custody for more than seven years, I can attest to the long-term damage such abuse does to children throughout the rest of their lives. It also spills over into following generations in a multitude of ways.

But the damage goes far beyond that inflicted on children for speaking Maori. Government officials from the country’s earliest days have explicitly held views and instigated policies that limited the academic opportunities of Maori students, simply because they were Maori. New Zealand had race-based policies for over 100 years. Even when those policies were no longer official, they have persisted unofficially.

John Thornton was a Victorian Pakeha man of his time, but he was also something of an anomaly in that he believed Maori were just as capable of academic success as Pakeha. He stated, “What led me to this idea was that I felt the Maoris should not be shut out from any chance of competing with English boys in the matter of higher education. I saw that the time would come when Maoris would wish to have their own doctors, their lawyers, and their own clergymen, and I felt it was only just to the race to provide facilities for them to do so, especially in an institution which was a Maori endowment.”

And so he identified students with academic ability for the matriculation exam to gain entrance to university. Ngata was the first Maori university graduate and went on to an illustrious career that benefited not just Ngati Porou but Maori throughout

the country. Probably his greatest achievement was when he and Pomare and Hiroa carried out a health campaign that improved sanitation and housing, and vaccinated a huge number of Maori against diseases that had decimated Maori communities for decades. This led to the resurgence of the Maori population that continues to this day. In doing so he essentially defied the widespread belief when he was growing up that Maori were a dying race.

But Thornton’s assumptions made a number of people in the education system deeply uncomfortable. Such was the opposition to his teaching philosophy that it led to a commission of inquiry in 1906. One of those who sat on the panel was none other than Apirana Ngata, one of his former pupils, who was now a member of parliament.

Ngata must have felt conflicted. He was leading efforts to retain Maori land and encourage Maori to farm it. So he was sympathetic to the argument that Maori students should get a practical education. But he had also benefited from the higher education that Thornton had made possible.

Changes forced on the school eventually restricted the academic opportunities Thornton had sought for his students. Academic subjects were scrapped and the doors to academia and the professions were virtually closed to Maori until the 1970s. There shouldn’t have been one Apirana Ngata, there should have been hundreds but they were blocked by a race- based policy. Ngata was just one of the few who slipped through the net.

St Stephens School, the famed boarding school for Maori boys.

Six years after the inquiry, Thornton resigned due to ill health. The resistance to his approach hadn’t been so much a backlash as a restatement of earlier attitudes and philosophies about the place of Maori in the young country. The establishment of the Native Schools in 1867 cannot be separated from a swarm of legislation that occurred throughout the late 1850s and on through the 1860s and 70s. The Crown’s wars against Taranaki, Tainui and other iwi, the confiscation of land, and the establishment of the Native Land Court are deeply connected to the establishment of the Native Schools. The whole project that these legislative acts represent was to reorganise New Zealand society for the benefit of Pakeha.

Hugh Carleton, a school inspector who was also a Member of the House of Representatives, wrote in 1862 that Maori education had a “double object — the civilization of the race and the quieting of the country”. He also stated, “Things had now come to pass that it was necessary either to exterminate the Natives or civilize them.”

In 1862, school inspector Henry Taylor said: “I do not advocate for the Natives under present circumstances a refined education or high mental culture; it would be inconsistent if we take account of the position they are likely to hold for many years to come in the social scale, and inappropriate if we remember that they are better calculated by nature to get their living by manual than by mental labour.”

In the view of some from this period, the education of Maori wasn’t to offer Maori a view on the wider world, it was to erase their world and their identity. F.E. Maning, a writer and Native Land Court judge, wrote in 1873: “If all your schools are going on as well as that of Whirinaki there will soon be no Maori in New Zealand.”

Maori had embraced European technology with alacrity for decades before the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. But they had also embraced the knowledge that they perceived lay behind it. Missionaries became popular partly because they offered literacy, which Maori adopted rapidly.

Maori children also held a different place in society than what missionaries were used to. “Early accounts written by Pakeha said Maori children were lawless, they did whatever they wanted, and they were never punished,” says Maraea Hunia. “They would argue and debate and they were on the marae whenever there was a hui. They were expected to give their opinions.”

But as settler numbers increased, Maori began to see education in European ways as necessary to cope with the increasing encroachment of Pakeha into their lives and communities.

The Native Schools were set up by design to prepare Maori students for low-skilled manual occupations and to culturally assimilate them by stripping their language. But even the manual and agricultural training was at a lower level than that offered to Pakeha. Maori were to work in agriculture, but not at a level where they would compete with Pakeha that were being offered the lands the Crown had taken from Maori. If Maori were going to be educated, then their access to knowledge was to be limited in order to prepare them for the place they were supposed to occupy in the Crown’s schema.

W.W. Bird, inspector of Native Schools from 1903 to 1930, stated that the whole purpose of Maori education was to prepare Maori “for life amongst Maoris” and not to encourage them to “mingle with Europeans in trade and commerce”. He asserted: “The idea was that [Maori boys] should learn only such trades as they might use on their return to the settlement. That is the whole idea of Maori education — to fit them for life amongst Maoris… If I met a Maori boy in Auckland, I should tell him it was his place to go back to his home and work there as soon as he could.”

In a word, segregation. By keeping Maori at a subsistence level in rural areas they would neither compete with Pakeha farmers nor trouble urban Pakeha.

W.W. Bird stated outright that, as a matter of government policy, Maori should not be given access to the full range of occupations. “The natural genius of the Maori in the direction of manual skills and his natural interest in the concrete would appear to furnish the earliest key to the development of his intelligence.”

In 1915, he said that it was departmental policy to discourage Maori from seeking access to the power of knowledge and the opportunities that provided: “So far as the Department is concerned, there is no encouragement given to [Maori] boys who wish to enter the learned professions. The aim is to turn, if possible, their attention to the branches of industry for which the Maori seems best fitted.”

This explicit official attitude continued for decades. Some couldn’t even cope with their own surprise that Maori — indeed, any “dark races” — might be as gifted as white people.

In 1931, T.B. Strong, the Director-General of Education stated baldly: “Whenever I have come in contact with the education of the dark races, Maori, Samoan, Fijian or Indian, I have noted with surprise their facility in mastering the intricacies of numerical calculations. This fatal facility has been taken advantage of in the Mission Schools and even in the schools manned by white teachers to encourage the pupils to carry arithmetic to a stage far beyond their present needs or their possible future needs.”

It doesn’t seem to have occurred to Strong to ask Maori what they thought their present and future needs might be.

In his history of Maori Schools, Separate but Equal? Maori Schools and the Crown 1867-1969, historian John Barrington documents how policy- makers in New Zealand were heavily influenced by the education policies for African Americans and Native Americans in the US, as well as schools in British colonies in Africa. These schools consistently gave a lower-level education that was focused on manual skills and deliberately denied students access to academic subjects. This was explicitly based on the racist assumptions that the students weren’t capable and shouldn’t be prepared for higher education and the professions. These ideas were adopted by high- level New Zealand educationalists from the late 19th century and well into the 20th.

Barrington says that many education officials “believed that virtually the entire Maori race, except for the occasional rare individual, was suited only to a practical kind of education. Such attitudes contributed to successive generations of Maori students being condemned to limited educational, occupational and life opportunities, an outcome often overlooked or ignored in attempts after 1960 to explain and analyse Maori under-representation in areas like tertiary education, or negative comparative statistics in other areas.”

If attitudes to Maori boys were prejudiced, Maori girls were an afterthought. In 1931, Strong stated that education “should lead the Maori lad to be a good farmer and the Maori girl to be a good farmer’s wife”.

The irony was that by this stage Maori had lost most of their land anyway.

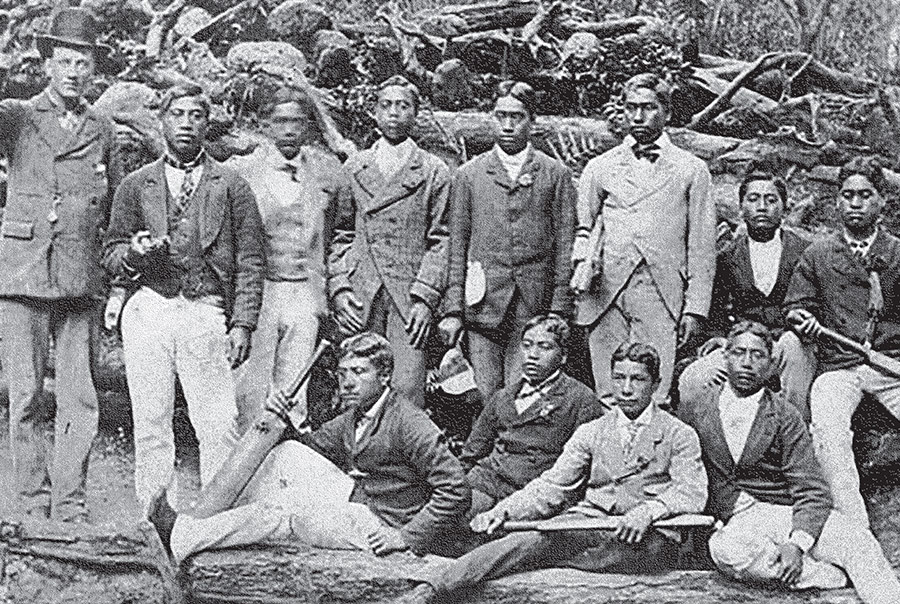

Students at Te Aute College in 1880, two years after John Thornton was appointed headmaster.

Prof Christine Rubie-Davies of the University of Auckland has a career as a teacher and education academic spanning 50 years.She is an expert in how the expectations of teachers — often bound up with attitudes held by wider society — affect children of minorities. She has seen the same patterns repeating in international literature and her conversations with overseas researchers.

“It doesn’t seem to matter in which country you do the research, there’s always a minority group who seems to cop it. So in the Netherlands, that’s Turkish and Moroccan, in New Zealand, it’s Maori. It just doesn’t seem to matter where you go, there always has to be some group [for who] people have low expectations.”

But she says there is often an irrational reaction when this is exposed as bogus by solid research.

“Quite early on, I did a study around the expectations of New Zealand, European Maori, Pacific and Asian students in primary school. Expectations were lowest for Maori, even though they weren’t achieving at the lowest levels.” “One of my master’s students did the same kind ofstudy in secondary math classrooms, and got exactly the same results. She went back and interviewed teachers about why they had low expectations of Maori. And the things that they said were just unbelievable, stuff about how ‘their families aren’t educated, so they can’t support them,’ and things like ‘I watch Police Ten 7, they’re always Maori.’”

“It was just horrendous. And these are teachers in our secondary schools. Most of them are probably still there now because it was only 2015.” The research got picked up by the media and there was a vicious backlash. “We got all kinds of disgusting, racist emails as a result.”

She says streaming is simply another example of the education system finding ways to exclude Maori students from opportunities. The logic behind it doesn’t stack up when looking at results.

“Once you’re in a particular stream, it’s very difficult to get out of it. If you’re in a low stream, you get these boring, repetitive skill-based kinds of activities. And if you’re in a top stream, you’re getting exciting, challenging, learning opportunities that keep extending your learning. So the gap gets wider and wider.”

Rubie-Davies says much of the resistance to getting rid of streaming can come from Pakeha parents who believe doing away with streaming will disadvantage their children. She has been researching data at an Auckland school that switched from streaming to mixed ability classes. The numbers showed that within a very short time the results of the lower ability students had risen while the top students’ results were not affected.

Professor Christine Rubie-Davies is an expert in how teachers’ expectations a!ect children of minorities.

“The things that they said were just unbelievable, stuff about how ‘their families aren’t educated, so they can’t support them,’ and things like ‘I watch police Ten Seven, they’re always Maori.”

“The data clearly shows that the high achievers are still moving. It’s just that these other kids catch up.”

The low expectations of Maori students is deeply entrenched in New Zealand’s educational history and deeply entwined with its racist past.

“A lot of the policies, like native schools for example, meant that Maori could only be educated to [age] 12. Maori were never expected to actually have an academic education. The effect is that we have had generation after generation of Maori who were punished for using te reo, and then we also had generations who were not well educated because they couldn’t access secondary level or higher level kinds of education.” Rubie-Davies says we see the results today.

“John Thornton kind of smashed those ideas because he let Maori boys come into his secondary school and have an academic education. And we got Sir Apirana Ngata, Peter Buck, Maui Pomare, there was a whole group of Maori boys who went through there who then went on to become doctors, lawyers, politicians. They had huge influence on New Zealand society.”

The influence of those who put an emphasis on Maori healthcare continues today. The Maori population doubled in one generation between 1936 and 1961 and, while that surge might have flattened somewhat, Maori numbers are still on an upward trajectory. By contrast, Pakeha numbers are set to decline over the next 20 years as Pakeha Baby Boomers die and while the birth rate is too low to replace them. The inevitable increase in the Maori workforce is going to have major impacts on our economy.

Approximately 40 per cent of the Maori population are children under the age of 18. For Pakeha the population structure is the other way around — around 40 percent are over the age of 50.

The education of that young generation of Maori will be a huge factor in deciding the economic well-being of the country.

Aaron Smale is North & South’s Maori Issues Editor, a role made possible by New Zealand On Air’s Public Interest Journalism. Next month, he investigates how the prejudicial education policies of 19th and 20th century New Zealand reverberate today.

This story appeared in the April 2024 issue of North & South.