Culture Etc.

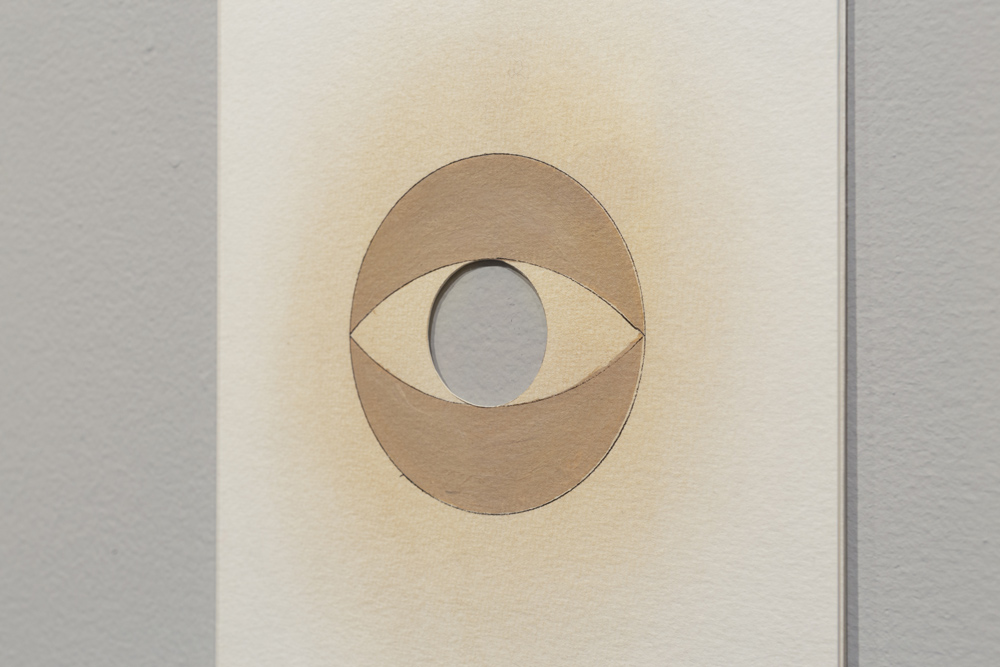

Meditation 5: Conjugation (detail), nacre and mixed media on plywood.

Divine symmetry

In her new exhibition, contemporary artist Julia Morison channels a new source of influence through her otherworldly art practice: the Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint.

By Theo Macdonald

In the mid-70s, freshly delivered from the art-school womb, multi-media artist Julia Morison (now 72) found herself swaddled in the spiky geometry of formal abstraction. You can visit Morison’s bespoke online archive to see grainy photos of these early experiments with shape and colour. But this rigid approach to painting didn’t stick. Why? “It just wasn’t exciting any more.”

So Morison moved on. She began working with language, interested in how simple phrases could signify enormous concepts. She wrote the words “God” and “dog” back and forth over “sheets and sheets and sheets of paper,” until the meaning seemed lost. Yet she discovered that something was retained: a potency preserved by contrasting a powerful base symbol (God) with something equivalently primal (dog).

Morison has always loved the alchemical side of art, the transmutation of low-cost materials into valuable art.

Julia Morison. Photo: Conor Clarke.

Intrigued by the possibility of juxtaposing, manipulating and diagramming materials, as she had concepts, Morison next made paintings combining gold and dog shit. One was purchased by a public gallery, prompting angry letters to the local paper about wasted taxpayer money, a story she still laughs about. Morison has always loved the alchemical side of art, the transmutation of low-cost materials into valuable art. “I like the fact that it’s not precious to begin with,” Morison says, “and I’m going to make something precious out of it. That’s the challenge: to make something really beautiful.”

And Morison does make beautiful things. She has an astounding degree of control over the patina of her objects, producing immense expressions of material symbolism in gold, pearl dust, lead and wood, to give only four examples of her preferred substances. In a five-decade career, Morison has investigated endless forms, from a series of 100 ceramic heads to collaborations with Australian fashion designer Martin Grant. After the Christchurch earthquakes, Morison made 10 minimalist sculptures by mixing the silt from liquefaction with liqueur knocked over and spilt by the earthquakes, including cherry brandy and black sambuca.

Since she was in her 40s, she has suffered from rheumatoid arthritis. Many of her projects since then have relied on the support of assistants and collaborators. In the last few years, however, the doctors finally sorted out her drugs, and she’s been able to draw by hand as she used to. This return to drawing takes wing in her latest exhibition, Ode to Hilma, currently on at City Gallery Wellington.

Ode to Hilma at City Gallery Wellington.

Ode to Hilma’s centrepiece is 10 monumental new paintings, each measuring up to 3.6 x 2.4 metres, titled Meditations. In City Gallery, they occupy an exhibition hall that recently held 10 similarly proportioned paintings by celebrated painter and mystic Hilma af Klint. Born in 1862, af Klint is considered a pioneer of Western abstract painting, although her paintings were little known until the 1980s as she had specified her work should be kept secret until 20 years after her death.

Morison didn’t intend to travel from Christchurch to Wellington for the exhibition Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings (December 2021 through March 2022), but was invited by a friend heading north for the show, who suggested Morison might be interested. In Wellington, she found af Klint’s work gorgeous and ended up visiting twice more during the exhibition’s brief window.

Over the phone, Morison reveals that Ode to Hilma is the rare exhibition that came together relatively easily. In her 50-year career, Morison has always worked in units of 10, following the Sephiroth, or 10 emanations, in the Jewish Kabbalah (the 10 points of the tree of life). Examining af Klint’s The Ten Largest in Wellington, she imagined 10 new paintings overlaid in the same formation, so she pitched the idea to Kirsty Baker, one of the gallery’s curators. She received the go-ahead a few days later. “Sometimes you meet resistance,” Morison recalls, “and sometimes you just don’t.”

There are clear parallels between Morison and af Klint’s practices, despite being born 90 years and several oceans apart. Morison’s first encounter with Af Klimt in Wellington exposed her to new modes of symbolic language. It provided a model for the systematised iconography Morison has explored for over 40 years. Studying af Klint’s extensive writings, Morison discovered how, “She changes the meanings of things, she doesn’t decipher them to an end point.” The same is true for Morison, who works with a system of 10 icons, each with an associated material, such as pearl for a spiral and gold for a triangle.

Blood is one of Morison’s 10 materials, which once meant using her own blood. “It got out of hand,” she says. “I couldn’t take that much for what I was doing, so I started using sheep’s blood, but the whole notion of blood changed because I had friends that died from AIDS.” Now, Morison instead uses Dragon’s blood, a bright red plant resin.

In Ode to Hilma, Morison’s “Ten Largest” are paired with another recent body of work, Vademecum II (2022). This set of 100 drawings/paintings algorithmically integrates her 10 symbols and their 10 affiliated materials. In 1986, Morison completed the original Vademecum — named for a Latin term for a reference guide. In each of these grand projects, arcane, ritualistic substances like lead and excrement are combined with mundane drawing materials like butter paper and graphite, items easily purchased at any art-supplies store. There’s a tension in this intersection of the industrial and pre-industrial, supporting Morison’s claim that her work remains relevant in the present, even as it refers back to ancient knowledge systems like Kabbalah.

For the 100-piece artwork Vademecum II, Morison applies many materials, including rust and clay, to many substrates, including butter paper and lead.

North & South ask Morison how she keeps all these complex, multi-part projects in order. She replies that she tends to concentrate on one thing at a time. “I really don’t like having an unfinished project. I want to start a project and finish it.” With Ode to Hilma finished and hanging on the walls at City Gallery Wellington, her Christchurch studio is empty, a white room waiting for whatever comes next.

Julia Morison: Ode to Hilma is on until 19 May at City Gallery Wellington. Visit citygallery.org.nz for details.

This story appeared in the April 2024 issue of North & South.