Great expectations

Last month, North & South investigated how New Zealand’s 19th and 20th-century education system deliberately steered Māori students towards low-skill, low-paid employment. Is this still the case today? Aaron Smale reports in part two of a three part investigation.

By Aaron Smale

Manaaki Waretini-Beaumont is brimming with energy and possibility. She’s about to start a degree in environmental science at the University of Canterbury, and is buzzing with excitement. But it might not have happened.

“In 2020,” she tells North & South, “the University of Canterbury ran a six-week course for year 10s which aimed to get more Māori students into environmental science, and the sciences in general. A lecturer told the group that if you were passionate about science, got a degree, and stayed in touch with your te ao Māori, then it’s likely you’ll be able to find a job, because there are hardly any Māori scientists. I kept that in the back of my mind, and carried on the sciences throughout my senior years.”

Before that course, science wasn’t an obvious pathway for Manaaki (Te Ati Haunui-a-Paparangi, Ngāti Rangi, Ngāti Apa me Ngāti Uenuku). “In year nine and 10, I really didn’t like science,” she says. “I wouldn’t engage in the class. It wasn’t until the end of year 10 that I saw myself in the curriculum — there was nothing I could relate to in the learning until that course.”

Manaaki is the first in her family to go straight from school to university. Her story could be framed as a simple one of an individual working hard and the world offering up its rewards as a result; of everyone having equal opportunity and it just being a matter of grabbing those opportunities; of a Māori student proving success is within reach for everyone, regardless of race, if only they would just apply themselves and take responsibility.

None of that would be untrue. But that telling would leave out significant parts of not only her story, but the experience of many Māori students throughout the country and over the entirety of New Zealand’s formal education history.

Manaaki Waretini-Beaumont is studying towards a degree in environmental science at the University of Canterbury. It almost didn’t happen. Photo: Ngāi Tahu

The top two were white, and, as you went down, they got browner and browner and browner. That just made no sense to me. Are you saying that intelligence comes only with a certain colour of skin?

“At the end of year eight,” Manaaki remembers, “the students looking to attend Avonside Girls’ High sat three tests: maths, patterns and English. From that test, we were put into streamed classes. The top two were the extension classes, and had next to no people of colour in them. The bottom class was filled with Māori and Pasifika students, and by year 13 they had either dropped out or were barely scraping through. So how they were treated in year nine really had an effect on the rest of their schooling.

“From the moment the Māori and Pasifika students stepped into the school, they were seen as not intelligent. Teachers that teach Pākehā girls how to get excellence will teach us how to pass with achieved. It was when Mrs Law came in that this pattern was broken.”

Catherine Law is the principal of Avonside Girls High. British-born, she has been teaching in New Zealand for more than 20 years, and has found some of New Zealand’s teaching philosophies dated, particularly around streaming. After teaching at Westlake Boys High School in Auckland, she took up a position at Hasting Girls High.

“I went down to the Hawke’s Bay, and that’s where I really saw the deficit impacts of streaming: a lot of schools using one test to segregate students into specific classes that were very clearly A through Z. The top two were white, and, as you went down, they got browner and browner and browner. That just made no sense to me. Are you saying that intelligence comes only with a certain colour of skin? The school was 87 percent Māori and Pacifica. Are you saying that out of the 87 percent there’s no bright kids in that group?”

Law says the problem is compounded, because, “What they call the top classes are getting great knowledge and education, and the students in the bottom classes are getting a worksheet or colouring. One teacher said to me, ‘I gave them colouring today and then they had behaviour issues.’ Of course, they’re bored. I’d be bored.”

The Ministry of Education’s position today is that streaming is not recommended practice. However, New Zealand has one of the highest rates of streaming in the world. Furthermore, while streaming into different groups has declined, timetabling decisions can effectively exclude Māori students from different subjects — if physics clashes with a te reo Māori class, an assumption has been made that there won’t be any students that want to take both.

The increase in the Māori population relative to the Pākehā population means the education system is going to have to increasingly address the needs of Māori students, not just for the sake of the students but for the future of the country’s economy. The inevitable increase in the Māori workforce is something that can’t be ignored. Fortunately, the changes Law was making at Avonside coincided with work within Ngāi Tahu and Tainui, and other organisations concerned with educational outcomes for Māori.

Kaya Renata-Staples with her son Elaiy.

“When you’re one of the only brown faces around, especially in primary school, you are always aware of certain perspectives you see in the media and on the news. So you try your best to sit outside of that. It was easier to be white.”

Kaya Renata-Staples (Ngāpuhi, Te Arawa, Kai Tahu) is every bit as confident and articulate as Manaaki. However, it’s only a few minutes into a conversation about her education history that her voice cracks, and her eyes glaze with hurt.

“When you’re one of the only brown faces around, especially in primary school, you are always aware of certain perspectives you see in the media and on the news. So you try your best to sit outside of that. It was easier to be white.”

Renata-Staples is now a researcher/social innovator at Tokona Te Raki, a social innovation hub within Ngāi Tahu that explores ways to improve social outcomes for not only Ngāi Tahu children and youth, but for all Māori within its tribal boundaries. During discussions around education, Renata-Staples began to understand the pathway that had been mapped out for her at school. It was that revelation that caused her to question how her family had been treated, and how her own children were starting to view themselves at a young age.

“I left high school at year 13 with NCEA level one because I was streamed, not because I was dumb, or didn’t deserve level three.” She followed her parents into a factory job and then worked in hospitality. She doesn’t regret it, but does wonder, what-if? Understanding what happened to her in the education system has made RenataStaples determined to make sure it doesn’t happen to other Māori kids, including her own.

“I’ve got kids, and I was thinking about their experience, so I asked them what it feels like to be grouped when they’re reading. My oldest son said, ‘Well, I’m in the dumb group. My best friend, he’s in the top group. And I wonder why he’s in the top group and I’m in the bottom group.’ At such a young age, he can see the comparisons being made that I’ve seen only by coming into this job.”

As Renata-Staples talks, her colleague Rangimārie Elvin (Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāti Pukenga, Kāi Tahu) is nodding in agreement. One of the challenges she faced was almost having to choose between being academically successful and being Māori, as if the two were mutually exclusive.

Rangimarie Elvin felt like she had to choose between taking te reo Māori and academic subjects when she was at school.

“In primary school,” Elvin remembers, “I was always told ‘you have so much potential’, ‘you’re so clever’, and all that sort of stuff. And then, once I got to high school, I thought, ‘Maybe I’m not actually that clever, because I can’t get any higher marks than what I’m trying to get.’ I had to keep working to keep up and make sure I didn’t get streamed into another class. There was always that fear that I was going to get put in the cabbage class.

“I wanted to learn my language back then,” she continues. “And I wanted to go into te reo classes, but I was told, ‘don’t go in those, you’ve got so much potential.’ So I didn’t get the opportunity to go and actually be a part of my culture. I was completely separated from it by teachers trying to encourage me to stay away from Māori subjects, telling me that there’s no point, no use, no value in speaking te reo Māori.”

One of these women’s roles is to encourage school students by raising expectations and giving them the knowledge and tools to challenge the school system if it isn’t working for them. Renata-Staples says part of her responsibility is empowering rangatahi to see that the system they are sitting in has been designed to make sure that “you kind of fail in a way”. “We’re seeing it in the data and statistics every year,” she says.

Eruera Tarena, the executive director at Tokona Te Raki, wants to unpack those statistics to see what might be done to change them. Ngāi Tahu and Tainui got together with The Southern Initiative from South Auckland in 2019 to commission economic research provider Business and Economic Research (BERL) to carry out some research on the results Māori students were getting, and the outcomes for them into young adulthood.

Tarena says, “We can describe and rattle off statistics around inequality, but we don’t have a story around why. So when we talk about Māori inequities, we often reinforce the idea that it was the fault of Māori — a personal choice. We’re blind to what is causing a problem and we have a really unsophisticated understanding of what is behind it. I think that contributes to racism.”

He says the research identified streaming as one contributing factor sending Māori on pathways with negative outcomes. “We started off with racial inequity, then we worked backwards from that with the data, and rangatahi involvement, and we go, ‘Oh, here’s a concrete practice which causes all of this harm. And there’s all this evidence that says this is a harmful practice internationally, a widely acknowledged contributing factor to racial segregation and all sorts of bad shit. But it’s still here, like it’s invisible.

“That problem blindness,” Tarena continues, “leads people to blaming Māori for being bad at maths. The reality of it is a practice, a policy, and a whole bunch of ideas which become these self-fulfilling prophecies.”

He says there is also a problem of putting the results in front of certain demographics that don’t want to hear or do anything about it. “How can you show Pākehā Baby Boomers how their future prosperity is going to be harmed by racism? Because again, if you just keep holding people back, you’re limiting their potential, you’re constraining their incomes. But when Māori are 20 percent of the workforce, and Pasifika are pretty close behind, there’s your superannuation gone.”

“Oh, here’s a concrete practice which causes all of this harm. And there’s all this evidence that says this is a harmful practice internationally, a widely acknowledged contributing factor to racial segregation and all sorts of bad shit. But it’s still here, like it’s invisible.”

Tarena says the political rhetoric around punishing Māori youth is counterproductive when around 40 percent of the Māori population is under the age of 18, while around 40 percent of the Pākehā population is over the age of 50.

“An ageing Pākehā working population heading into retirement is going to be propped up by a young thriving brown workforce. So as much as they try to punish them, even right-wing neoliberals, can’t they see that they’re disadvantaged by that in the long game? That’s how stupid racism is.”

BERL chief economist Hillmarè Schulze was working as senior economist for Africa at the World Bank in the early 2000s when she ran into New Zealand’s education minister at the time, Hekia Parata, who quipped that she should come and work for Māori.

“I specialise in indigenous economic development,” Schulze says, “but then I came to New Zealand and loved it.” She has an abiding interest in how the education system is performing — or not — for Māori students.

In South Africa, where Schulze was educated,it is a compulsory part of the school curriculum to learn not only your own language but another of the languages spoken there. Schulze herself speaks not only English, but Afrikaans and Sotho, one of the many African languages of South Africa. She finds it slightly perplexing that some New Zealanders have an aversion to the Māori language. “It’s mind boggling that New Zealand doesn’t totally 100 percent embrace te reo Māori, because this is your language. It just makes no sense to me that you get New Zealanders that don’t.”

BERL was approached by Eruera Tarena to try and unpack what was going on for Māori in education and what that meant for career pathways. As Schulze describes it, “Eruera wanted us to actually investigate where the traditional educational pipeline might need to be tweaked or adjusted. And he wanted to have a really good idea of what that actually looked like in terms of where the pressure points were, and what they could focus on as Ngāi Tahu to support rangatahi through this education pipeline.”

The government’s integrated data infrastructure was limited in what it could tell about education outcomes before 2008, so BERL took two cohorts, of around 50,000 and 30,000 students, that could give a snapshot of trends for Māori students over a 20-year period. Those numbers were then crunched down to give a representative 100 students, and where they had ended up by the age of 25. The numbers show some encouraging signs, but also persistent trends that can’t be ignored without serious consequences.

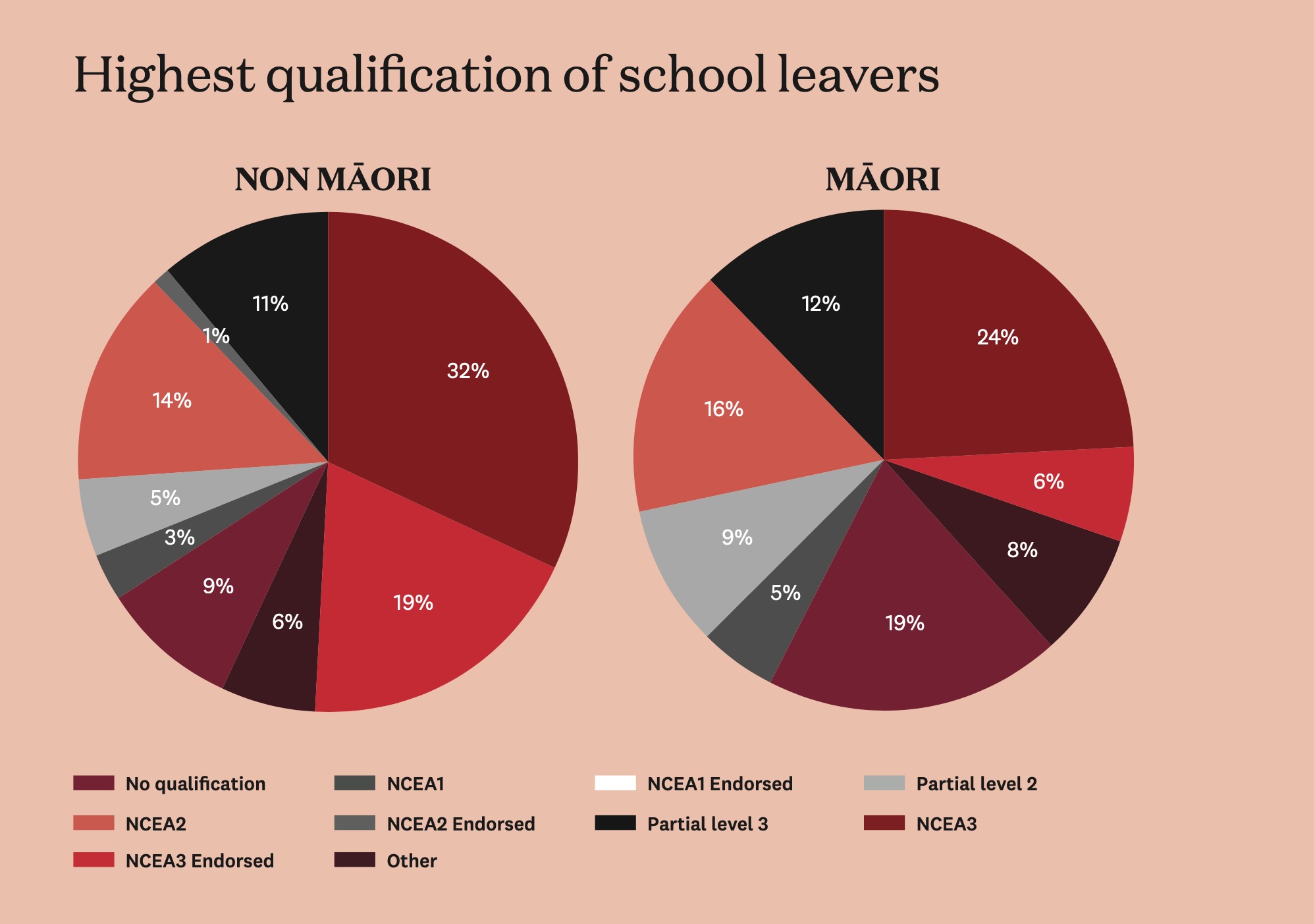

Nineteen percent of Māori school leavers were leaving with no qualification, compared to 9 percent of non-Māori. Just six percent of Māori were leaving with NCEA Level 3 endorsed with merit or excellence (a recognition of high achievement), compared to 19 percent of non-Māori. These results at school flow through to career and income, which show Māori lagging in many areas. Accounting for the significant differences in the age profile of Māori, BERL has found an income gap of $2.6 billion per year. Perpetuation of this inequality with the growing Māori population will cause this gap to grow significantly. By 2040, this is projected to grow to $4.3 billion.

Schulze says these numbers show the need to address inequities, particularly in light of the growing Māori population and the ageing Pākehā population. “Education is an economic conversation. Economic growth is a means to an end, because it gives you choices and opportunities. And I think those are the things that we should focus on.

“[In] the 1840s, Maori ran the entire economy, and they were empowered. Māori have strongly advocated in the last 50 years to get back to an economic conversation. Our education system needs to support everyone to be able to excel.

“We should look at our education system to make sure that the next generation of rangatahi Māori have the tools, the skills and the support to pursue higher education. The next generation of our workforce is going to be Māori and Pacific and we want them to have high-paying and high-quality jobs. We can’t afford this low-wage economy, otherwise you and I won’t be able to get a pension.”

Hana O’Regan is the chief executive of Tātai Aho Rau-Core Education, a non-profit NGO that works in education. She grew up hearing her father, Sir Tipene O’Regan, constantly talking about the changes in New Zealand’s demographics, and the need to upskill the next generations of Māori.

“In the 1990s,” she recalls, “Dad was giving a lecture at the accounting school at Victoria University. I remember him drawing on the chalkboard — it wasn’t even a whiteboard — a simple graph showing population growth. He showed the difference between Māori and Pākehā, and the economic cost not getting these things right now would have on the country.”

“Statistics New Zealand have been telling us this forever, but it’s almost like the decision makers seem to be blind to that. Or at least it’s not a priority. They’re not seeing the catastrophic results of having the biggest growing part of our population continuing to be the most disenfranchised, disengaged and unskilled. It’s the same approach to climate change, it’s not like we don’t know what’s going to happen.”

O’Regan also believes the failure to address inequities for Māori in the education system is going to have real consequences for the country’s ability to provide for the ageing Pākehā population. “We’re not going to be able to maintain the future that people might expect for our elderly if we don’t do something drastic now.”

Christopher Luxon has recently come out and highlighted low rates of school attendance, but his tone is punitive: It is the students and parents that are in the wrong. Luxon’s government intends to fine parents whose children aren’t attending, but there is little attention given to some of the reasons some children may not be going to school — the impacts of poverty and the failure of the education system for Māori over a long period of time

“So,” O’Regan says, “we’ll punish the people who are hurt already. You’ve got people in large numbers of communities where girls who’ve got their periods don’t go to school because they can’t afford the sanitary gear. And you’ve got people who can’t afford a uniform for each one of their kids, so the kids wear the uniform on different days.”

Shortly after Luxon’s announcement, the NGO Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) released a report which estimated that around 15,000 children were working 20-50 hours a week on top of trying to go to school, to help their families make ends meet. “No one should have to choose between their education and putting food on the table for their family,” said CPAG convenor Alan Johnson.

In the end, the impact of educational failure for Māori doesn’t fall on the educational system that is paid billions to educate children. The consequences fall on the children and their whanau. “It’s not the teacher that gets put into prison,” O’Regan concludes.

Levin teacher Hoani Perigo grew up expecting a future picking carrots. A family windfall sent him to Scots College where his whole life changed. Photo: Aaron Smale.

Levin teacher Hoani Perigo might not have been headed to prison, but says that growing up in Raetihi he was quite likely destined to pick carrots. “The aim of everybody was to leave school, pick carrots, pick swedes, that’s it. I didn’t see a buy-in from our teachers, and there were no teachers there I could actually relate or bond to.” So he was a bit of a truant.

Perigo had a parent who’d been hit by teachers at school for speaking Māori. “I think [my mother] hated school because she couldn’t speak English and wasn’t allowed to speak Māori. There was no success there. She left school when she was 12 or 13.” Although his mother later saw the importance of education, Perigo says he was following a similar track for different reasons.

“I had speech impairments, glue ear, probably dyslexia… My brother couldn’t read until he was about 20. His wife taught him. No teacher taught me to read, I learned by reading Superman and Batman comics. I learned how to do maths because I worked in my parents’ shop — we had a couple of dairies, one in Waiouru and one in Raetihi. No one taught me anything. I could barely speak English.”

What jolted Perigo out of taking a well-worn path to paddocks of carrots was a jolt to the whole family’s finances. His dad, who’d spent time in the army, worked as a security guard at a timber mill. When that closed, he got $20k paid out in redundancy.

“They spent that 20 grand on me to go to Scots College, because they knew I wasn’t going to school.

“So when fifth form at Scots College came, I sat down and studied, studied, studied. And that was unbelievable, for a Māori kid from Raetihi sitting down studying. And I got the best in geography and in history. In physics, I think I was 38 or something — pretty bad — so I studied and studied and I think I got to 12. All I wanted to do was beat everybody.”

Even now, Perigo is intensely competitive. “My class has to be the best at everything. I don’t like losing.”

It was when he was at teachers college things suddenly began to make sense. So many Māori kids like himself didn’t value education because the education system didn’t value Māori kids.

One of his classes at teachers college was around education policy, and he remembers being floored learning that the policy until the 1970s was that Māori were labourers. Perigo has now been teaching for three decades, and has noticed the lingering hangover from those policies. He has also seen a tendency among teachers to favour kids that are like them, not just in economic and racial background, but in how they view those who aren’t engaged in learning for whatever reasons.

“Teachers are people who’ve been successful in education. So 80 percent of them, probably even 90, have always been successful in their own education. You put them in front of a classroom, and they don’t understand why these kids are not doing what they are told.”

Graph from BERL.

One of the main reasons he sees is trauma. In one low-decile school he taught at for more than a decade, there were periods he was spending most of his time dealing with the trauma and stress the kids were experiencing outside the classroom. “They see their parents struggling: ‘Gotta get money, gotta pay the rent.’ Rents keep going up. Food bills are going up. Petrol is gonna keep on going up.”

To combat this stress, Perigo believes there needs to be a light at the end of the tunnel. “That’s what I’ve always said. They’ve got to have a goal to aim for. But there’s no goal to aim for if you’re in survival mode in the house.

“Trauma follows you,” he says. “It doesn’t go away. We need to start treating causes, not the symptoms. Teachers can treat the symptoms, we’ve got all the tools in our toolbox to handle the angry boy, but we don’t have the tools to treat the causes.

“Some parents are working two jobs, three jobs, but they’re all minimum wage, and the stress upon the family increases. So with no money comes family violence, the other partner takes off, and then you’re even worse off. You’ve got no money, family violence, drugs, separation. And then as an education system we pick up the pieces. How do you pick up the pieces? Well, we can offer them a secure environment at school. But they still gotta go home, don’t they? That trauma is still at home.”

Last year, Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr effectively announced that he was going to create a downturn in order to keep inflation down. One of the outcomes will be unemployment.

No one has said it out loud, but have economists and politicians implicitly decided that Māori are the economy’s buffer? That they are the permanent five percent of unemployed that the economy needs to keep inflation under control and wages down? Is this the function Māori now have in New Zealand society, to take the pain for everyone else? Is this the latest iteration of deliberate policies to keep Maori on the lowest rung of the economy?

Perigo says the stresses that economic hardship causes in Māori communities and whanau falls particularly heavily on Māori boys.

“You’ve got trauma, attachment issues, anxiety, and then you’ve got all the academic problems. As these boys reach eight, nine or 10, they realise that academically they’re behind their peers. They can work even harder, but you need a support structure around you to do that, or you start playing up.”

One of the ways he has addressed this as a teacher is to personalise the learning for each child, recognising their strengths and also taking into account some of the issues the child is facing outside the classroom.

He says he gets tired of hearing lazy solutions to the problems facing teachers and their students. “The latest is to get rid of cell phones. Well, this computer is pretty much a cell phone. My iPad is a cell phone. My watch is a cell phone. I mean, what year are you living in?

“I still love teaching, but it does get harder. To me, it’s not the kid’s fault. Who made that angry kid? What is he angry at? Once again, go back to the beginning. Let’s treat the causes, not the symptoms.”

Aaron Smale is North & South’s Māori Issues Editor, a role made possible by New Zealand On Air’s Public Interest Journalism. Next month, he concludes his investigation by delving further into educational outcomes for young Māori boys, and looking at the reopening of St Stephen’s School, of which he is an old boy.

This story appeared in the May 2024 issue of North & South.