Power Play

While one in five households report having trouble paying the power bill, and one in eight are cutting back on heating because of the cost, the big four electricity companies’ gross earnings for 2022/23 totalled $2.61 billion, or about $7.1 million a day. Are we being ripped off by the electricity generators? And, if so, what needs to be done about it? Michael Fletcher investigates.

By Michael Fletcher

Luke Blincoe, CEO of Electric Kiwi, is an affable, cheerful sort of bloke, but when it comes to New Zealand’s electricity market, he’s not one to mince his words. In mid-September he wrote a bluntly worded email to the company’s 70,000 customers that, among other things, accused the big four electricity companies of “squeezing retail competition out by subsidising their bloated retail arms with the excess profi ts from generation”. He also told his customers that Electric Kiwi had lodged a formal complaint with the Commerce Commission.

The “big four” he’s referring to are the large generator-retailer (“gentailer”) firms Contact, Genesis, Mercury and Meridian Energy, which between them generate over 80 percent of New Zealand’s electricity and have about 85 percent of the residential retail electricity market. His comment was prompted by the release of the four companies’ annual reports for 2022/23 showing record high combined gross earnings of $2.6 billion. A level of earnings which itself followed last year’s record of $2.28 billion. Combining generation and retailing is not uncommon in other countries, but is typically accompanied by regulations and systems to ensure independent retailers can compete fairly against electricity companies who both sell them their power on the wholesale market and compete with them in the retail market.

As an electricity retailer, Blincoe obviously has skin in the game but he’s not the only one expressing concerns. Consumer NZ has also been raising questions about the structure and performance of our electricity markets and the size of the gentailers’ profi ts. Consumer NZ CEO, Jon Duff y, says a survey by his organisation showed the cost of energy was a concern for 60 percent of New Zealanders. It estimated that 40,000 households have gone without power sometime in the last 12 months for cost reasons (see “Power and the Powerless”). In that context he says, “the optics of huge profits at the height of a cost-of-living crisis are not great… We acknowledge that profi ts are a healthy and normal part of business, but there’s a question around what is excessive.”

Robin Morrison, Power pylons, near Winton, circa 1979. Photo: Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

“The optics of huge profits at the height of a cost-of living crisis are not great… We acknowledge that profits are a healthy and normal part of business, but there’s a question around what is excessive.”

Blincoe and Duffy’s use of the e-words — “excess” and “excessive” — is significant. The existence, or otherwise, of excess profits is a critical and disputed question. In economists’ terms, excess profits, broadly defined, are profits over and above what a firm would make in a competitive market. As Marcia Poletti, a New Zealand-born executive at Octopus Energy in London, explains, in many US states the regulating agency uses an algorithm to automatically override any generator’s selling price offer in the wholesale market if it is judged to be using temporary market power to raise its offer price. Ultimately, if the market rules aren’t working, the losers are us — the ordinary residential power consumers who wind up paying extra for our electricity, while also missing out on the benefits of innovation a properly competitive market would lead to. So, do the gentailers have market power (sorry, the pun is unavoidable in this topic) and, if so, are they exercising it to their benefit and consumers’ cost?

Geoff Bertram, an economist working until recently at Victoria University of Wellington, has studied the electricity sector for more than 30 years. His answer to both questions is an unequivocal yes. He described it in a 2013 paper as a “straight wealth transfer from consumers [to the gentailers], reflecting the exercise of market power”.

New Zealand’s

electricity markets

The shape of our present-day electricity sector reflects its origins in the reforms put in place during the heyday of pro-market ideology in New Zealand in the 1980s and 1990s. The so-called “Bradford reforms” were named after the National Party’s Max Bradford, Minister of Energy from 1996–99, although in fact the process began earlier, under the Labour Government of David Lange and Finance Minister Roger Douglas. Under the reforms, the old Electricity Department was broken up into the government owned and controlled Transpower, which was responsible for the national grid, and four gentailers established as State-owned enterprises (SOEs), with the big hydro dams and other generation assets allocated between them. Local power companies, many of them community-owned trusts, were required to choose to sell off either their retailing business or their local lines networks (most opted to keep the lines). Under the 1986 State-owned Enterprises Act, SOEs are required to act as commercial competitive entities, maximising returns to their government owner. Alongside these SOEs was one other big privately owned gentailer, Contact Energy, plus a few smaller generators and a small number of electricity retail firms. In 2013/14, the four SOEs were semi-privatised, becoming listed companies, with the government retaining a 51 percent cornerstone shareholding in each firm. Finally, in 2022, Mercury bought out Trustpower, making it the largest electricity retailer in the country, and taking what was ‘the big five’ down to the big four.

The theory behind the reforms was that allowing electricity firms to set their own prices in a competitive market would drive efficiency, leading to the best possible deal for consumers. Consistent with this belief, the regulatory regime was deliberately established to be as light-handed as possible. The main tasks of the oversight body, the Electricity Authority, were to monitor the sector, encourage maximum competition and to ensure barriers for new investors to enter the market were not artificially high. If this story sounds familiar, at least to readers of a certain age, it is because it was. This was the period of peak corporatisation (and privatisation) of state-run activities. In electricity terms, it was unquestionably radical — few developed-country jurisdictions have no direct regulatory control over maximum prices. Supporters argue that, overall, the reforms have proven successful. They point to the fact that there are now almost 40 retailers that consumers can choose between. The chief executive of the Electricity Authority, Sarah Gillies, while acknowledging that some regulatory settings will need to continue to evolve, notes that the authority’s May 2023 review of the wholesale market “concluded that the electricity market has served consumers well [and] competition is most likely to deliver the best outcomes for consumers”. Gillies also notes that the non-integrated (ie, non-gentailer) retailers’ share of the market has risen from 2.8 percent in 2009 to around 16 percent now.

Benmore Dam is the largest dam within the Waitaki power scheme. Photo: Benmore Dam by Simon Bloomberg;

But evidence of competition is sometimes in the eye of the beholder. Consumer NZ is rather less persuaded that we have seen competition that serves us well, and Paul Fuge, its electricity sector specialist, sees that same 16 percent figure as an indicator that competition has been very slow to emerge.

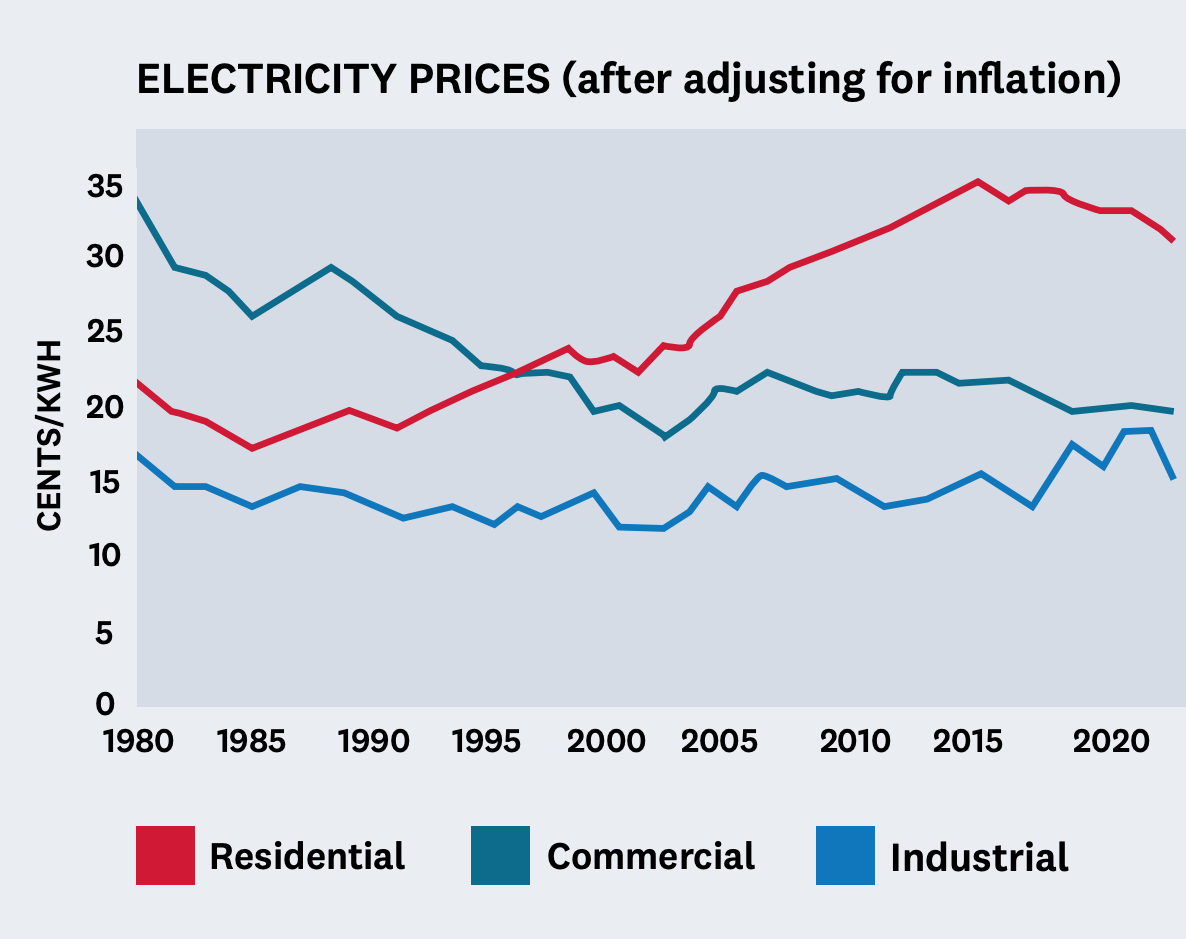

Consumer NZ also notes the large rise in the price of electricity since the reforms were introduced. Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (MBIE) data shows that since 1999 the price of electricity sold to residential consumers has risen by 35 percent after adjusting for inflation, even though the increase has been less than inflation in the last five years (see Figure 1). Had the price increased at only the same rate as other household costs over the last 23 years, what is a $200 power bill now would be less than $150. While there are other reasons for some of this increase — investment in new lines, an increase in GST, among others — the question remains as to why the freemarket model has not delivered lower prices. These doubts are reinforced by the fact that the increase has all been on residential customers. Larger industrial users who typically have more bargaining leverage have not experienced any inflation-adjusted increase over the period, and for commercial users the price has fallen.

Profits or excess profits?

At the heart of the electricity market debate is whether the big four gentailers’ operating profits reflect a fair return on capital in a competitive market or also include extra profits resulting from their having been able to take advantage of having market power, so-called “market power rents”. In economists’ terms the word rent is more general than rent on a house or land – it’s an unearned gain that comes from owning something, in this case that something is market power. Bertram describes New Zealand’s electricity market as a “rent-seeker’s paradise” and says bluntly that the companies’ behaviour is “price-gouging” – getting a higher price because their power in the market means they can. It’s not that our prices are high by international standards – they aren’t, thanks mostly to our access to low-cost hydro power. Rather, the concern is that they are higher, much higher, than they would be if the large gentailers were not making excess market-power profits.

The first in-depth study of the wholesale electricity market was undertaken in 2009 by Professor Frank Wolak of Stanford University for the Commerce Commission. Wolak estimated market power rents of $4.3 billion over the six and half years to June 2007, equivalent to 18 percent of total wholesale market revenues. Wolak’s methodology was criticised by some, and Treasury described it to Ministers as “not credible”. The Commission, for its part, accepted the findings but, tellingly, concluded that “[t]he exercise of market power to earn market power rents is not by itself a contravention of the Commerce Act, but is a lawful, rational exploitation of the ability and incentives available to the generators”.

In other words, the Commission was saying that the Commerce Act which governs their responsibilities had no problem with use of market power to increase profits, per se, only with improper market behaviour like collusion. As a result, no action was taken. The relevant section of the Act – section 36 – was broadened last year which is one important reason why Electric Kiwi’s new complaint to them may prove to be a game-changer.

Steve Poletti, an associate professor at the University of Auckland’s economics department (he also happens to be Marcia Poletti’s brother), has been involved in two detailed empirical studies aimed at estimating the size of any market power rents in the New Zealand electricity sector. The first study, carried out with two others, used a different method from Wolak’s to address the criticisms made of Wolak’s approach. It used detailed data on real-life daily market behaviour and applied simulated computer-learning models to compare the difference between actual price outcomes and a theoretically competitive-market equivalent. It estimated total market-power rents of $2.6 billion dollars for the two years studied, 2006 and 2008. Poletti updated and extended this with a further study published in 2021. That research covered the seven years 2010 – 2016 and estimated very large market power rents of between $5.6 billion and $6 billion, equivalent to 37 percent to 39 percent of total market revenue.

Mercury Energy’s chief financial officer, William Meek, doesn’t accept these figures, arguing that “people do a whole lot of calculations” but that the easiest approach is simply to look at total returns to someone investing in the company. For Contact Energy, the firm that has been publicly listed the longest, he puts this at a quite reasonable rate of return of between 6.2 percent and 8.3 percent depending on the time period. Bertram and Fuge both reject Meek’s explanation outright. They point out that the gentailers have frequently revalued their generation assets in their accounts. As Bertram described it in an earlier paper, “Writing up assets, obviously enough, reduces the apparent rate of profit. That’s the trick the Commerce Commission signed off when it established its ‘regulatory asset base’. That’s why the commission’s regulatory accounts for 2013-17 don’t reveal any ‘excess profits’. The smoking gun lies buried under a mountain of asset revaluations.”

Another energy boss, Contact Energy’s CEO Mike Fuge (no relation to Consumer NZ’s Paul), told RNZ that his company’s recent profits simply reflect its new investment. “Just like when you put money in the bank, the more you put in, the more returns you expect, that’s just ordinary economics.” That may be a fair point, but it is not one that actually answers the question of whether Contact’s overall operating profits include a component of excess profits coming from exercising market power.

Labour’s Electricity Price Review

In 2018, Energy Minister, Megan Woods established a panel to conduct an electricity price review, which was part of the coalition agreement Labour had with New Zealand First. The panel’s final report made 32 recommendations covering topics from energy hardship through to increasing retail competition and “reinforcing” wholesale competition.

The review acknowledged concerns about excess profits but concluded, to quote the minister’s report to Cabinet, that the electricity industry works well in many respects although it would benefit from greater competition, and that the regulatory regime is working well in the current environment. It recommended expanding the Electricity Authority’s monitoring role and requiring gentailers to report separately on the financial performance of their wholesale and retail arms, rather than any structural reform such as legislated separation of generation and retailing (aka “vertical separation”).

Bertram’s view is that the review’s recommendations, and the minister’s responses, were too weak and have in fact worsened the situation. He believes that the industry was expecting the minister to do more and that after 2018 “excess profits go through the roof” as a result of the big firms “relentlessly manipulating the market knowing they were going to get away with it because they had a clean bill of health from the inquiry”.

The review placed heavy emphasis on better billing information and encouraging consumers to shop around as ways to improve retail competition. It recommended merging the Electricity Authority’s and Consumer NZ’s price comparison websites. (This has now happened, and Consumer has the sole contract for running its Powerswitch site.) Consumer NZ’s own research estimates the average potential saving households could make by switching provider is approximately $385 per year, but they are concerned at the relatively low rate of switching taking place. Jon Duffy agrees a part of the issue may be apathy on the part of consumers, although he says it is relatively easy to switch suppliers (albeit somewhat less so for people who have bundled their electricity and internet services together). Mostly though, he interprets it a sign that retail competition is not as strong as it should be, that it is hard for the smaller independent retailers to make sustainably lower-priced options available to consumers. Marcia Poletti says part of the problem is what she somewhat colourfully calls the power companies’ “tease and squeeze” strategies. They understand that ordinary customers with busy lives and a million and one things to deal with are slow to switch providers, so they entice new custom in with a good introductory offer and squeeze you later once you’re an established customer.

One of the review recommendations that all players seem to agree on is to ban so-called “saves” and “win back” offers. These are special offers made to a customer only when they notify their intention to switch or immediately after they have done so. Such offers are never publicised so allow the offering company a means of retaining customers while at the same time avoiding having to offer its best possible deal to all its other customers. In effect, non-switchers are used to subsidise the better deals offered to those who threaten to switch.

Where to from here?

Not withstanding the views expressed by gentailer representatives, it seems hard to avoid the conclusion that there is at least prima facie evidence that the big four may be making excess profits as a result of being able to wield their market power, and that they have may have been doing so for many years. Those profits benefit their private and government shareholders through dividend payouts and share values. Just as in the case of the supermarket duopoly, to the extent that this is occurring, the biggest losers are us, the ordinary household residential customers. Electricity is an essential service and the consequences of being overcharged range from being a wealth transfer the better-off can, but shouldn’t have to, cope with, through to the estimated 100,000 households facing energy hardship.

So where to from here? What is needed to fix the problem?

That depends on who you talk to. Some, such as the Electricity Retailers Association (ERANZ), an umbrella grouping that includes the large gentailers, say that now is not the time to disrupt the sector, when the primary focus must be on achieving the transition to 100 per cent renewable electricity by 2035. ERANZ Chief Executive, Bridget Abernathy, points to the billions the big four are planning to invest in renewable, wind, solar and geothermal projects to move New Zealand closer to 100 per cent renewable electricity and meet an expected increase in demand as the country transitions away from fossil fuels.

The Electricity Authority also believes the sector is serving customers well and that structural reform, such as separating generation and retailing, “would not guarantee any benefits for consumers but would create risk of unknown consequences”.

Others argue that the transition to fully renewably electricity generation does not require allowing the existing electricity market structure to continue. A 2021 report by the Council of Trade Unions and Unite Union recommended that the government should take over the Huntly coal and gas plant and other fossil-fuel based facilities and “ring-fence them for strictly non-commercial use to ensure national energy security as the electricity [sector] undergoes its full decarbonisation process”. Huntly’s is the most expensive power to produce; when it’s in use and is the “marginal bidder” its costs set the wholesale price for the rest of the market. Phasing it out as much as possible would be beneficial both environmentally and economically in the wholesale market.

Some, including Dr Bertram and Marcia Poletti, go further. In their view, something quite fundamental is rotten in the state of Denmark. They see the market-competition theory as having failed in a complete, if totally predictable, way. Poletti suggests that, if we are going to continue with allowing the vertical integration of generation and retailing, intervention is necessary. She says we need to correct for marker power in the wholesale marker and eliminate cross-subsidies between the generation and retail arms of the gentailers. Bertram believes that beyond proper regulation, government should split generation from retailing. He also advocates for the removal of anti-competitive barriers that make it hard for the small but growing number of very small renewable generators (such as roof-top solar) from competing fairly with the big providers.

Consumer NZ’s Jon Duffy’s conclusion perhaps offers the most likely way forward. In his view, there is sufficient evidence that market competition has not worked as it was hoped, and that consumers have paid dearly for that fact. In his opinion what is needed is a Commerce Commission investigation. He emphasises that this should not be as narrow as the Electricity Price Review, but a full investigation into all aspects of the sector. He is encouraged by the recent broadening of section 36 of the Commerce Act and by the Commission’s apparently increased willingness to undertake full formal investigations such as it did in the supermarket sector. Duffy hopes that Luke Blincoe’s complaint to the Commission may just prove to be the catalyst that leads to lasting, meaningful change. If Steve Poletti’s calculations are even anywhere near accurate, that could make a massive difference to our power bills – and the warmth and healthiness of many people’s homes.

Box: Power and the Powerless

Toni Hoggard is a financial advisor at the Wellington City Mission. Most of the clients she deals with simply have too little money to meet their weekly expenses; many are struggling with debts that sometimes arise from poor decisions but more often are the result of desperation. Hoggard says the power bill is second only to rent when it comes to issues facing her clients. One of the problems Hoggard comes across regularly is clients who have been offered “free” goods like a fridge or television by power companies if they sign up to a special deal. She says, “they’re not ‘free’ at all. You pay for it later with high electricity prices.”

Where she can, Hoggard will get help from government agencies like WINZ or donations to City Mission schemes to help alleviate the clients’ debt problems. In quite a few cases she sets up a Total Money Management arrangement with clients where she takes over the management of their income and their bills. In one case she mentioned to North & South this means the household has $40 each week to cover their food and other spending. Her clients are lucky that in Wellington the not-for-profit Sustainability Trust has set up a small electricity provider, Toast Electric, which uses its profits to subsidise power costs for approved low-use customers. Toast caps its low-income users’ total winter bills and also makes personalised visits to customers’ homes to advise on power saving options.

More widely, the Electricity Price Review cited Statistics New Zealand estimates that 100,000 New Zealand households experience energy hardship, which was defined as spending 10 per cent or more of their income on power bills. They made eight recommendations to reduce energy hardship, including setting mandatory minimum standards for vulnerable consumers and banning prompt payments discounts which favour those with enough money to always pay on time at the expense of other consumers who can’t always manage that.

Kate Day, who has helped set up advocacy group Common Grace Aotearoa, is part of the Everyone Connected coalition, which is particularly concerned at the number of non-payment disconnections carried out by the big companies and the disconnection/reconnection fees they charge. In her view, such fees are simply targeting the poorest and imposing extra costs on them. “That is families going without heating, hot water and lighting, and under severe stress. It’s distasteful to hear about retailers’ profits when a portion of that comes from households who are struggling to afford a basic necessity.” Both Day and Jon Duffy, say that the pre-pay option some retailers offer shifts the risk of any unpaid debt off the power companies but costs around 15 percent more per unit than a household could get on normal post-pay arrangements.