The Queerest Capital

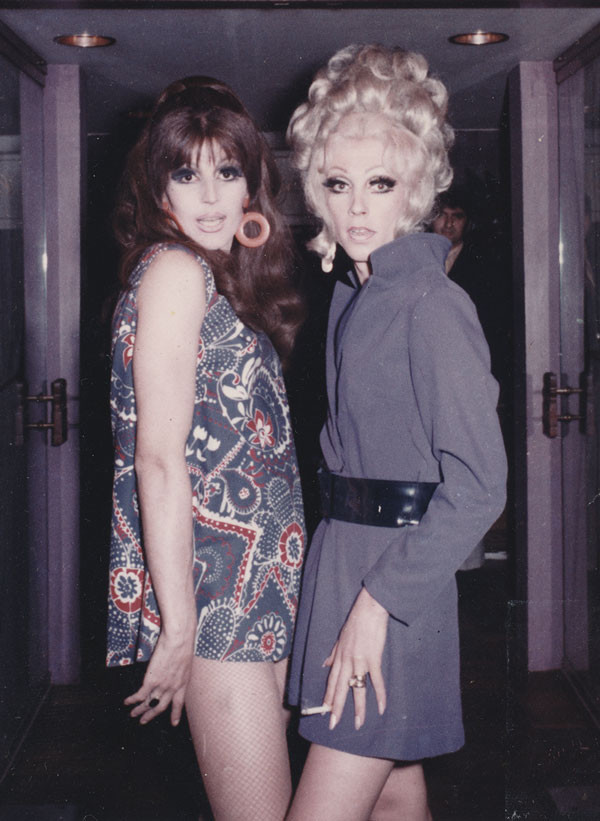

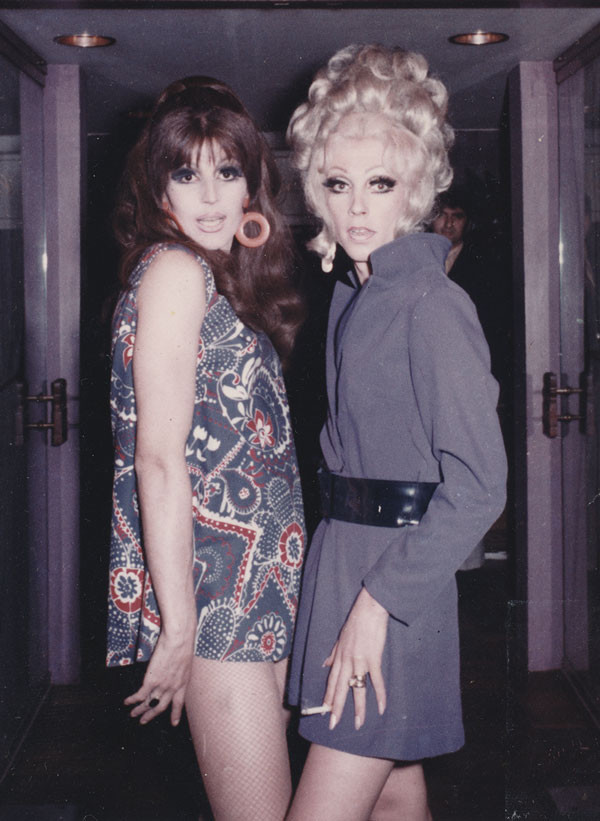

From 1964 to 1980, the visibility of transgendered women in Wellington was extraordinary. Many would operate their own businesses, one would stand for the city’s mayoralty, while the high profiles of the others tested the limits of legal and social discrimination. David Herkt discovers the secret history of Aotearoa New Zealand’s transgender capital.

In 1964, at the age of 19, Niccole Duval arrived in Wellington to work as the only “female impersonator” in a troupe of performers organised by the Auckland promoter and sometime stage-conjurer, Wally Martin.

“It was the first time I had ever been to Wellington,” Duval explains. “I thought it was a magical city – and, as far as I was concerned. The police attitude was entirely different from Auckland. There was none of the nastiness they had in Auckland.”

The group had been given the opening residency at El Matador, a new dine-and-dance venue owned by Emmanuel Papadopoulos, a well-known member of the city’s Greek community.

“It was a spectacular restaurant with a catwalk through tables and chairs, and a stage down at one end. Bruno Lawrence was a jazz and rock drummer who would eventually go on to become a member of Max Merritt and the Meteors and a founder of BLERTA (Bruno Lawrence’s Electric Revelation and Travelling Apparition) which toured in a psychedelically painted bus. Later, he would win awards for his many film and TV roles.

“We stripped to live music in that show. Bruno was funny. He knew when you were taking off a glove and there would be a tickle and a crash of the cymbals – and it was timed to absolute perfection… He was also very handsome.”

At the time, women were not permitted to reveal their nipples to an audience and wore pasties. As a female impersonator, Duval was expected to conclude her act by finally removing her bra to reveal a young man’s flat chest.

“Emmanuel’s club didn’t go for very long. They were busy, so I don’t really know what happened. Wally Martin was always getting people’s backs up, so it could have just been something as simple as that.”

At the age of 80, Duval can look back on a well-lived life and her memories have become important. For the first time, the stories of previously marginalised communities are being recorded , and even feature in the secondary-school history curriculum.

Duval was born in 1944, the second son of a primary-school headmaster. Her father had an evening job in Auckland’s entertainment industry, managing the bar at events run by the Mrkusich family. She attended Mount Albert Boys Grammar, not far from her home, but left school as soon as possible.

“I was a terrible child,” Duval remarks, “I was a runaway train.”

She already knew the city well from nights of sneaking out from the family house to explore downtown coffee-bars like the Ca d’Oro, jazz clubs like the Picasso, sly-grog venues and even the one remaining Chinese opium den in Grey’s Ave. Duval’s first job, when she was 15 and a half, was stripping as a female impersonator at the Pink Pussy Cat on Karangahape Rd.