Madam President?

Too clean for green politics? What a Harris administration could mean for New Zealand and how the Biden White House fused environmental policy with industrial protectionism.

By Henry Whyte

To an American eye, Kiwi perceptions of our two main political parties must appear olde worlde. Despite some well-founded objections from academics and trade unionists, National are largely seen as abstemious economic managers, possessed of the Calvinist thrift necessary to get the country ‘back on track’ in times of strife, and keep their hands off the loot in times of asset inflation (housing bubbles). Labour are, by contrast, the well-meaning, heart-over-head party of — to use an outmoded Washington phrase — ‘tax and spend’.

When comparing the Kamala Harris Democrats to the Donald Trump Republicans, such descriptors have little power to discriminate. Trump doesn’t pretend to have a heart, and the Nancy Pelosi-edged pragmatism of the Democrats is even less sentimental. Attempts at wealth redistribution invariably involve tinkering in the margins — partial student loan forgiveness, increased capital gains taxes for households with incomes exceeding $1m/year, untaxed tips — rather than substantive change, and are blocked by Congress in any case. The heyday of economic management — Bill Clinton achieving successive budget surpluses at the end of his second term — now belongs to a previous age. One could even present a compelling case that traditional left/right economic policy divisions have simply wandered out of the American political arena.

So are they doing better than us? Surprisingly, yes. Both countries experienced crippling levels of inflation since the central bank money printers “went brrr” during Covid, with consumer prices in the US and NZ increasing, respectively, 16 and 18 per cent in the three years to June. Over the same period, however, US real GDP per capita has increased by 7.1 per cent; New Zealand’s has declined by 3.2 per cent. (Each figure measured in their respective currencies. It is worth noting that the US working age population has increased 1.7 per cent over this period, compared to 5.4 per cent in NZ).

…consumer prices in the US and NZ [increased], respectively, 16 and 18 per cent in the three years to June. Over the same period, however, US real GDP per capita has increased by 7.1 per cent; New Zealand’s has declined by 3.2 per cent.

The reasons behind such a divergence are inevitably complex and multifaceted, particularly considering the breadth and depth of the US economy, but differing legislative priorities provide some insight. The Sixth Labour Government was remarkably poor at infrastructure planning, let alone industrial policy. The current National government has promised new roads but preferred cost-cutting in virtually all other areas. Implicitly or explicitly, both parties apparently agree that large-scale decisions about economic direction are best left to the market, which naturally favours existing sectors (tourism, agriculture and property speculation), safe bets and manufacturing goods which are exportable and in which the country has a clear competitive advantage.

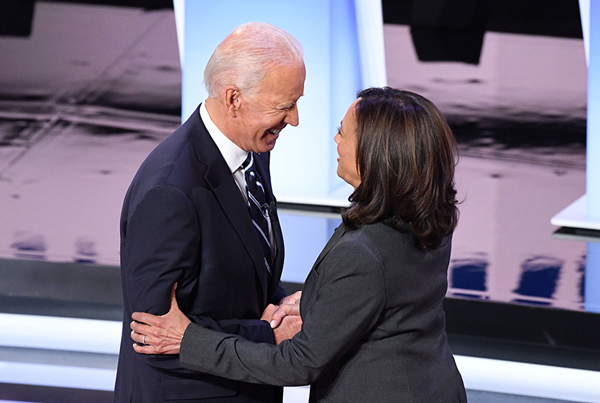

Joe Biden’s vision of the government’s role in economic planning has been radically different. In the first Congress of his term, when Democrats enjoyed a majority in the House of Representatives and exactly half of the Senate’s 100 seats, the White House used every available tool — including the Vice-President’s tie-breaking Senate vote, the budget reconciliation process to avoid filibusters and old-fashioned bipartisan outreach — to pass several substantial pieces of legislation, chief among them the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

Misleading name aside — it certainly didn’t reduce inflation — the IRA had several purposes. The most globally-significant involved various incentives for domestic production of “clean energy” technology, including tax credits and subsidies for US manufacturers of lithium batteries, solar panels and wind turbines. There were also “local content” requirements. The consumer credit for electric vehicles, for instance, depended on both the battery being manufactured in North America and the origin of certain constituent rare earth minerals.

To the European Union, which had already been subsidising green technology without concern for its provenance — arguing that environmental protection should supersede national economic interest — these measures amounted to protectionism. To the US, they were a necessary response to Chinese dominance in the sector, notably manufacturing solar panels, which had been aided by uncompetitive government intervention and low wages for several decades.