Culture Etc.

Christine Jeffs: Making A Mistake

Christine Jeffs latest film, A Mistake, is based on author Carl Shuker’s novel in which a surgeon’s split-second decision leads to dire consequences. Shuker talks to Jeffs about directing Hollywood stars and the love of horses that keeps her home.

By Carl Shuker

A middle-aged man, white collar and competent, enters a clearly Midwestern sporting goods store and asks the clerk if he can see a “20-gauge, maybe a Coach, or a Western Competition Special.”

The clerk hands him the shotgun and turns away, diverted by other customers.

The white-collar man produces a shell from his suit jacket pocket, loads the weapon and blows his own head off. Scene.

Next: the store is filled with cops and staff and there’s blood and teeth and hair on the ceiling, on the floor, on the staff, and everywhere. “Hey Carl! He’s over here in fishing too,” a walk-on says. One of the staff members in the background (a cast to his eye, or an ancient gunshot wound, that the camera lingers over) takes a call from his wife and discusses tonight’s lamb chops. And we pan past the pools of blood to the cleaners who have to clean this up.

Christine Jeffs is in her office on her farm in Warkworth, and tells me this really happened (the found extra with the damaged eye; the lamb chop call) and she simply saw it, and grabbed it on the spot. “Can you just say that again for the camera?” she apparently said.

We’re talking about her 2008 low-budget miracle of tonal control, her dark, loving family dramedy, Sunshine Cleaning. Shot in the bleak, high-desert, beautiful strip-malls of Albuquerque, New Mexico, the film is about two sisters, played by budding A-listers Amy Adams and Emily Blunt, attempting to redeem failure, debts and family struggle through the surprisingly lucrative business of cleaning up the blood, brain and severed fingers of crime scenes. This opening is a quick and genius scene, narratively compact and immediately compelling. And showcases Jeffs’ ability, with her long-term cinematographer (and life partner) John Toon, to recognise and capture these kinds of quotidian beauty, in formal observational frames within the confines of tightly organised screenplays that nevertheless focus on evolutions of feeling.

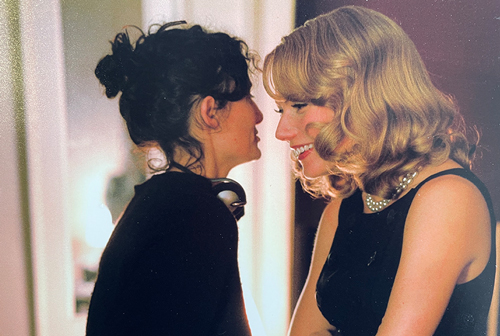

Take for example, another tiny moment easy to overlook. After 2001’s Rain, Jeffs’ breakthrough adaptation of the Kirsty Gunn novel that took her to a standing ovation at Cannes, Jeffs signed up to direct Sylvia, a biopic of Sylvia Plath, late in the process. There was a John Brownlow screenplay, a producer, and, at her hottest after the Oscar for Shakespeare in Love, Gwyneth Paltrow herself was attached, influential and passionate. A somewhat mega project, comparatively big budget, multiple trans-Atlantic locations, a period piece, a huge evolution from Rain, and wading into the hornet’s nest of the Plath legacy.

“Gwyneth had just won the Oscar,” I said. “There was a NZ$15 million budget. A period piece. Cars, costumes, Daniel Craig, Michael Gambon, Jared Harris, even Blythe Danner, Paltrow’s real mum, playing her mum. Weren’t you overawed? Wasn’t it intimidating?” “No, not really,” she said. “Really?” “Well, we shot at Cambridge on our first day on set, I was like, oh, I felt sick. But we’ve got a schedule in front of us. You just get down and do your job. One foot in front of the other. We just walk into it and keep walking. And Gwyneth was a joy to work with.”

Jeffs found and pushed the producers and financiers hard for a youngish Daniel Craig to play Ted Hughes to Gwyneth’s Sylvia. He was then a comparative unknown for a critical part in what is often a two-hander, attempting to sell one of the most famous love affairs of modern literature. She got her way.

In the scene I’m talking about, mid-film, Sylvia is trapped inside the cold Devon house, bare-board floors echoing with angry footfalls, and endlessly folding the clothes of their two young children. Her eyes are red-rimmed, hunted and haunted, and Ted is long gone to London, to success, and his poet-shaman persona and endless affairs. The pre-eminent poet, folding laundry, looks down at poor little Frieda filling page after page of her childish notebook with writing Sylvia cannot do. The camera sees that writing. Frieda looks up, proud of her work, wondering if her mum is too. Sylvia’s eyes full of disappointment, hunger and rage.

So: A-listers. A pre-Bond Daniel Craig. Amazingly unselfconscious child actors and multiple, global locations. Major theatre talents like Michael Gambon to wrangle. A perfectly accomplished period-look for a biopic of one of the most contested personalities and marital dynamics of the 20th century, for your second feature, and your first outside New Zealand.

And yet, still, Jeffs is utterly nonchalant, and practical. “I’ve spent the morning shoveling horse shit,” is the first thing she tells me, and laughs. Breathtakingly matter of fact about what she does and what she’s achieved. Stroke, for example, her first short film where she met John and which took them to Cannes for the first time, and opened the gates for Rain. I assert something about Stroke being a metaphor for a woman breaking into a masculine world to do her own thing by at first appearing to play their game. “Nah,” she says. “Stroke was purely because I love celluloid. We shot on 35 mm and I edited on 35 mm. I wanted the visual cacophony that 35 mm is and to just cut it and edit it and tell this very simple little story.”