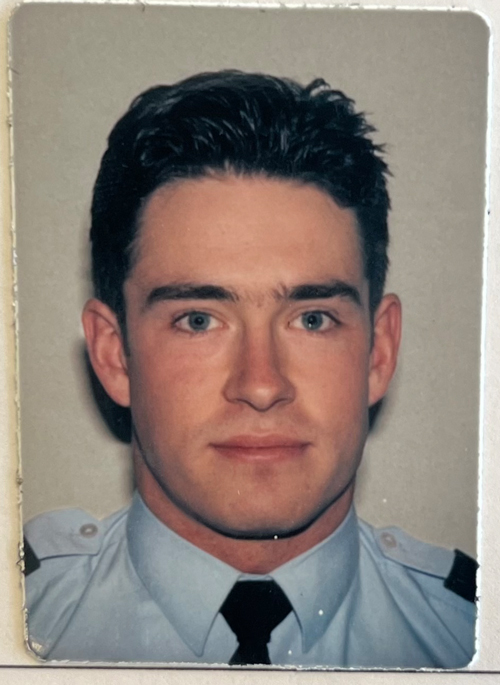

Top cop

Writer John Sinclair talks to the Chief Police Commissioner Andrew Coster on the eve of his departure for the shores of social reform.

By John Sinclair

All the other original cast members from that top-rated daytime drama of 2020 have now moved on. All the other original cast members from that top-rated daytime drama of 2020 have now moved on. David Clarke, Jacinda Ardern, Ashley Bloomfield, Caroline McElnay, Grant Robertson, Chris Hipkins, stars of the 1pm daily Covid briefings that had us glued to the set, have all made their exits; and now finally the Police Commissioner, Andrew Coster, instantly recognizable as the only one wearing a uniform, is moving on too. What’s more he’s leaving behind his uniform.

Like many a departing high-profile CEO nowadays he’s moving into a role in ‘investment’ – except in this instance we’re not talking about high finance. Andrew Coster will be taking up the helm at the Social Investment Agency, a stand-alone agency that reports directly to Finance Minister Nicola Willis about how best to direct social services spending for long-term benefit, about which more later.

Coster took over the job of Commissioner of Police at the start of April 2020, three days after the first Covid lockdown began. The worst of times — and perhaps in some ways the best of times — to start a new job. His predecessor, Mike Bush had shelved plans to go on a long-planned family holiday to Italy, and was moved sideways to lead the All of Government Response Group. (Given that Italy was at that time experiencing a deadly wave of Covid cases, that may not have been a great sacrifice.)

What was it like, at the most ‘unprecedented’ moment of public turmoil in living memory, stepping into the role as enforcer-in-chief of a new set of ground rules for the whole community, policing a collective leap into the unknown, except that what we did certainly know was that people would get sick and die, perhaps in their tens of thousands, that the economy would tank and that some of the cherished freedoms we enjoy as individuals and families would be severely curtailed?

Coster comes across both as a man with a plan, and one prepared to put the plan on hold when the situation calls for new thinking and a clean sheet.

“In leadership you work with the circumstances as they are served to you.” A crisis as large as Covid is a break point: there’s huge disruption, but also opportunities to learn something new and valuable about how to harness the goodwill and unity of a whole society. Amidst the ferment of Covid, he made sure to set up a strategy and culture team within the police national office to ensure the organization could, like all large enterprises, “pivot” to cope with the novel realities forced upon them.

He is complimentary about how New Zealanders responded to a new, restricted and regularly shifting set of social ground rules – at least for the first few months, and in comparison to other countries which he wouldn’t name, but didn’t need to.

“Policing is very rarely about force; it’s overwhelmingly something you do by consent”, he comments. “As police we are always testing our social license, and it shifts constantly with the mood of the community and changes in things like where and how people get their information.”

“We’re always adjusting how we use the Four ‘E’s of policing.”

The four ‘E’s?

“Engage, then Educate, then Encourage, and only if necessary, Enforce.”

A lot of the early work during Covid was about engaging and educating. Overwhelmingly, people wanted to do the right thing — they just needed to know exactly what that was, which at times was difficult. It was a new situation for all of us. Nevertheless, Coster says, “Police was deliberate about choosing carefully our enforcement approach to Covid controls.” He contrasts us with Australia, where the police acknowledge they moved too quickly into enforcement mode, and lost some social license which they are still struggling to regain.

Inevitably, public support for our Covid controls grew thin. Fatigue and irritation set in, and then turned to anger for a segment of the community. But by the time that happened the kind of chaos seen in other countries had been averted, and an effective vaccine was available (admittedly that created a whole new tranche of social license issues of its own).

From his office window in Police HQ in Thorndon, Coster can see Parliament grounds where, in February 2022, groups opposed to the government’s Covid restrictions occupied the front lawn. After three weeks, on 2 March, as we all know, 500 police officers moved in to remove the occupation.

“They had the right to protest”, he comments, of the group which swelled to several thousand at its height, “and Parliament grounds is absolutely the right place to do so. In fact, beyond a radius of around 100 meters people would have hardly known they were there.”

But once the protestors’ points had been emphatically made, it was time to move on, and many did just that. At its end, the thousands had dwindled, but a hard core of 268 remained.

“Hindsight is easy”, Coster says, “and though there are always lessons to be learned, the occupation had become hugely disruptive for businesses and schools in the vicinity”. The legitimacy of the protest ended when it became an occupation, but Coster believes it was right to tread cautiously in using the fourth E.

“If we had gone in hard during the early days, I’m quite confident we would still be managing the consequences of that in terms of a small group of very disaffected people in the community.”

“Fundamentally I believe we managed that protest well, and the Independent Police Complaints Authority affirmed that in their review.”

Other challenges have marked his tenure as Commissioner, notably fixing the regulation of firearms and addressing an uptick in gang violence and youth crime, in particular ram-raids.

The Christchurch mosque shootings shone a harsh light on the shortcomings in how the police had been managing firearms regulation. Coster acknowledges it was a failure in “getting the basics right”, and is confident that the system has now been “fundamentally transformed”.

Firearms are front and center in the gang world too. As Coster points out, over the past decades the gangs have fluctuated in size and strength. Prominent in the 1980s and 1990s, gangs were in decline in the early 2000s, with many members “ageing out”; but then methamphetamine came along, and there were huge amounts of money to be made. Add to that the fact that, among the s501 deportees repatriated from Australia, there were a small, but influential number of gang leaders who brought with them a new level of professionalism, had effective links with international crime networks, and a greater proclivity for using violence. It was the interaction between these new groups and the established gangs, the encroachment on existing territories, that led to a violent escalation in turf wars.

Understanding the root cause helps, but, as Coster says, “In the near term enforcement does matter.” He notes the “huge investment” in constabulary growth of 1,800 sworn officers during his tenure, and some significant victories. However, with the amount of money to be made in the drug trade, the battle is far from won and police tactics need to be constantly adapting.

Solving problems at their roots remains a priority, and one which Coster will be addressing more squarely in his new role. “We need to think about the underlying factors that make particularly a group of young men vulnerable to thinking that gang membership is their best life option.”

He points out that when police looked at a cohort of ram raiders, young men driving stolen cars into dairies and jewelry stores, they found that more than half had first appeared on their records before the age of three, as children present at a home where a violent incident has occurred. The progression from a violent, dysfunctional home environment, through disconnection with schooling, untreated health issues, petty crime through to serious offending and gang membership seems obvious with hindsight. Interrupting that trajectory for the generation now in infancy is something police can only hope to achieve through partnerships with others. “To use a rugby analogy, police are the forwards, and often the halfbacks, but we need to pass the ball out to the backs and make sure they are well-equipped and know what to do with it. Good work is happening throughout social services, both state-provided and in the not-for-profit sector, but we need to get a lot more consistent in getting the right intervention to the right place at the right time.”

Youth crime and gang violence is just one of the issues Coster will be addressing at the Social Investment Agency. It’s a central agency, alongside the Prime Minister’s Department and others, and has its origins in Sir Bill English’s argument that we need to mine the wealth of data gathered over decades across many state agencies to understand “what works” in social spending (and what doesn’t work). He will be reporting directly to Finance Minister Nicola Willis and the agency has a mandate to range across the social sector, where billions of taxpayer dollars are spent annually, to find out how to get investments in the right place, using the most efficient models and ways of commissioning.

As with policing, Coster is clear that “we can’t just rely on the State to fix everything”. There’s a key role for NGOs, for philanthropic support, and for the business sector, with many larger businesses fully appreciating their role in fostering a cohesive society where young people get a good education, have role models and mentors, and experience the anchoring effect of steady employment.

Things are not getting easier, however. “The breakdown in social cohesion is a concerning trend, driven to a large degree by social media, and it’s a global trend.

Even so I’m confident there are things we can do to mobilize the goodwill that’s in the community to greater effect.”

As he hangs up his uniform, Commissioner Coster is happy with the way police culture has developed over his 28 years in the force. The changes the Commission of Inquiry into Police Conduct recommended in 2007 have been substantially implemented. “It’s a much more diverse organization now than when I joined, with a much greater breadth and depth of thought. It’s a place which offers new recruits an opportunity to make a difference in communities by preventing crime and harm.”

“It’s a marvellous career for a young person”, Coster crows, lapsing, with a chuckle, into shameless recruitment mode. “It offers a breadth of opportunities, a sense of purpose and lots of variety. It’s been very good to me.”