Little Girl Lost

March 13, 2025

Missing person files are, by definition, a sad lament. When it’s a child, acutely so. The disappearance in 1949 of 2½-year-old Elizabeth Shannon, who wandered off and vanished is still etched into the minds of many who lived in Wellington at the time.

By: Scott Bainbridge

In February 2025, an independently-arranged large-scale excavation was initiated at the property of an old factory in the Adelaide suburb of Castalloy.

Fifty nine years earlier, two teenage boys were instructed to dig a grave-like hole for the factory manager, Harry Phipps. Within the last 10 years, Phipps was named as being the killer of the three missing Beaumont children, one of Australia’s infamous missing person cases.

On Australia Day, 1966, Jane Beaumont, 9, and her younger siblings Arnna, 7, and Grant, 4, caught the bus to Glenelg Beach. They were seen at some point on the beach with an older man who was never identified. The Beaumont children were never seen again.

Over the years, several notorious child murderers had been accused and, incredibly, all were believed to have respectively been in Adelaide on that day.

Circumstantial evidence uncovered in the last few years lends credence to the probability the children were killed by Phipps, whom it has only been learned was related to them. Their parents, Jim and Nancy, died in recent years never finding out the truth about what happened to their three children.

I’m reminded of a little-known New Zealand case where the parents of missing Petone child, Elizabeth Shannon died over 60 years later not knowing what happened to their beloved daughter.

According to the missing person statistics, there are 342 people listed as historically missing since 1939, the earliest year these records were officially recorded.

While each case is tragic, there are none sadder than the disappearance of a child. The disappearance of 2½-year-old Elizabeth Shannon in 1949 remains one of New Zealand’s lesser-known mysteries, but the memory of the little girl who wandered off and vanished is still etched into the minds of many who lived in Wellington at the time.

Bill Shannon was a returned serviceman who had spent much of WWII in the RNZAF.

In 1948, he and his wife Hilda shifted to Wellington with their infant daughter Elizabeth who was born a year earlier. Housing was in short supply and with high demand, the family temporarily moved in with Bill’s sister, Joan and her husband Jim Caldwell in their house at 47 Fitzherbert Street, Petone.

The Caldwells had a son, David, who was six months older than his cousin, Elizabeth. The pair were great mates and were inseparable.

At the beginning of November 1949, Hilda was admitted to Wellington Public Hospital where she gave birth to her second child, Terry.

On Friday 4 November, Bill finished work at the usual time and headed home. He planned to visit his wife and newborn son in hospital after tea. His sister Joan was preparing dinner while keeping an eye on the children.

Jim Caldwell finished work around 5pm and, when he arrived home, he and Bill played outside with the children before heading inside.

Elizabeth could not talk properly but in her own language made baby sounds, pointing to her father’s brown leather RNZAF flying helmet.

Bill pulled it down from the shelf and placed it on his daughter’s head. Wearing the helmet around was a favourite game for Elizabeth. It was way too big for her head but she loved wearing it. She giggled with delight and raced back outside, closely followed by David.

Their fathers remained inside and talked of weekend plans.

Already storm clouds were closing in, but they hoped the weather would hold off so they could take the children to the local fireworks display the next day.

The parents listened out for the children, and could hear them chattering and laughing as they ran around chasing each other and digging in the dirt. Minutes later, around 6pm there was silence.

The fathers went outside to check on the children but they were nowhere on the fully enclosed section. The back yard gate leading out to Fitzherbert Street they always ensured was shut was wide open.

The Caldwells and Bill Shannon raced outside and along the road yelling for the children.

Fitzherbert Street was a narrow residential street, but only 230 metres from the busy main road, The Esplanade, which runs parallel to Petone foreshore. Directly across the road were the main gates to the Petone pier and beyond this, the sea.

The children had never wandered off by themselves before, but would have known the route to the beachfront because of their daily walks there. Elizabeth had a fondness for seashells and would spend many happy hours playing on the beach with her family.

As the fathers raced along Fitzherbert Street, neighbours heard the commotion and rushed outside to help. Bill reached the beachfront at 6.08pm and scanned the shoreline. There was no sign of either of the children.

Around 6.30pm, little David Caldwell was found standing alone crying in nearby Jackson Street. The relieved fathers asked the small boy, almost three, where his cousin was. David was unable to talk properly yet. At the mention of ‘Bee’, the family’s pet name for Elizabeth, he pointed towards the foreshore uttering her name.

By now, neighbours were checking surrounding streets and knocking on doors. A large group assembled at the beach. Despite darkening skies, it was still adequately clear enough to see a fair distance along the beachfront and out to sea.

It was estimated the maximum time Elizabeth would have been gone could not have been more than 20 minutes. Her little legs could not have carried her too far. Whatever direction she walked would have required her to cross reasonably busy roads and pass at least 100 residential homes. It was dinner time and people were returning home from work. She should have been spotted by someone.

At dawn the next morning, Petone police along with officers and cadets from the police college met at the Petone Beach Gates and formulated a search plan. Hundreds of volunteers turned up to help. A pilot from Wellington Aero Club made low sweeps across Wellington Harbour between Somes Island and the Petone coastline. Two whaling boats manned by Navy League Sea Cadets and various local dinghies headed out to make shoreline sweeps but there was no trace.

While it seemed logical that she was around the sea-front, it would’ve been impossible for her to gain access to the beach because the gates to Petone wharf closed at 5pm. She was too small to clamber over the sea wall. On the chance she had, the tide at Petone was safe and it was at low tide, but if she entered the water, the winds could have swept her towards the eastern bays. The police launch focused their search around this area. After 6pm it was low tide and shallow for some considerable distance. A child could wander about 50 metres before encountering difficulty. Elizabeth loved playing with shells on the sand, but was not naturally attracted to the sea.

It was established that around 6pm Friday, there were still a lot of people around the shorefront. Most of them did not notice the two small children. One witness saw two small children, one wearing an Air Force helmet running across Union Street towards the Esplanade about 5.50pm. Another noticed two toddlers at 6pm standing on a strip of lawn staring intently at some teenagers kicking a ball against the wall of the Petone Rowing Club. A few minutes later, several witnesses saw David running across the busy Esplanade into Nelson Street crying.

While the search along the shoreline from Petone and around to Eastbourne remained the focus, a large contingent of searchers were diverted to parks, factories, disused buildings, and sheds along the Esplanade. The Gear Meat Company factory and the Petone Mill were large properties which each had numerous small shacks or nooks and crannies a small child could navigate. The search area fanned outwards towards the Hutt area. With no clue found, the official search was called off after 10 days.

There was a rarely used public footpath between the timber yard and the Petone railway crossing. Workers used to park their cars there and therefore a toddler of Elizabeth’s height walking between cars and high fence could have easily been obscured. One early theory was she had been accidentally run over by someone not paying attention or drunk. Realising what happened, the driver placed her in the car with the intention of driving her to the hospital, but she died en route. Rather than face the prospects of serious charges, he or she disposed of her body somewhere remote.

On Wednesday after she vanished police received an anonymous tip-off saying a small girl was seen wandering into the Gear Meat Company towards a sump on the rear of the property. Police secured the site but abandoned the search at mid-morning, satisfied she was not there. Unfortunately, local radio stations frequently reported the news that Elizabeth’s body had been found at the Gear Meat property. This was distressing to her family and frustrating for police who had learned the call was a hoax.

As search teams were scaled back, police began to examine the theory Elizabeth had been abducted. When she was discharged from hospital, Hilda Shannon made a public appeal and thanked police and the public for their efforts. It was their opinion Elizabeth had been picked up by a woman who could not have a child of her own and appealed for her safe return. This was four years after the end of the war and there was a close community spirit. People felt safe and looked after each other. It was incomprehensible that Elizabeth could have been abducted, let alone anything evil had resulted.

Yet within weeks of Elizabeth being reported missing, the abduction scenario was being considered by Wellington CIB. Detectives commenced a parallel investigation into the activities and behaviour of known child sex offenders in Wellington. Two men were brought in for questioning; a 60-year-old fish curer had been arrested and charged with three counts of indecently assaulting three girls aged between 7 and 10 at Newtown Zoo and at nearby park. A 42-year-old kitchen hand had recently been arrested for exposing himself and attempting to assault a seven-year-old girl on the cable car. Both men were extensively grilled and denied being in Petone on the day Elizabeth vanished, and their respective alibis stacked up.

Experts today believe it was unlikely she was taken by a paedophile. Why wasn’t David snatched too? Even though it was investigated, the abduction scenario was considered unlikely because it would have been unplanned and spontaneous because nobody would have known the children’s movements at the time. The offender could have walked past and opened the gate. The family always ensured the gate was shut securely and the children were too small to reach the latch. Against this is the fact witnesses did not notice any adult with them or anything to cause suspicion.

What prompted David to run off without his cousin? Did someone or something scare him? Where was Elizabeth? Something happened to her between 6pm and 6.08pm – eight minutes.

The search for Elizabeth Shannon was one of the most extensive in New Zealand history at that time. Searches extended to the Hutt hills and Hutt Valley, with many areas covered twice. When I interviewed her in 2007, Elizabeth’s aunt, Joan Caldwell, believed the fact no clues were ever found and the investigation just stalled.

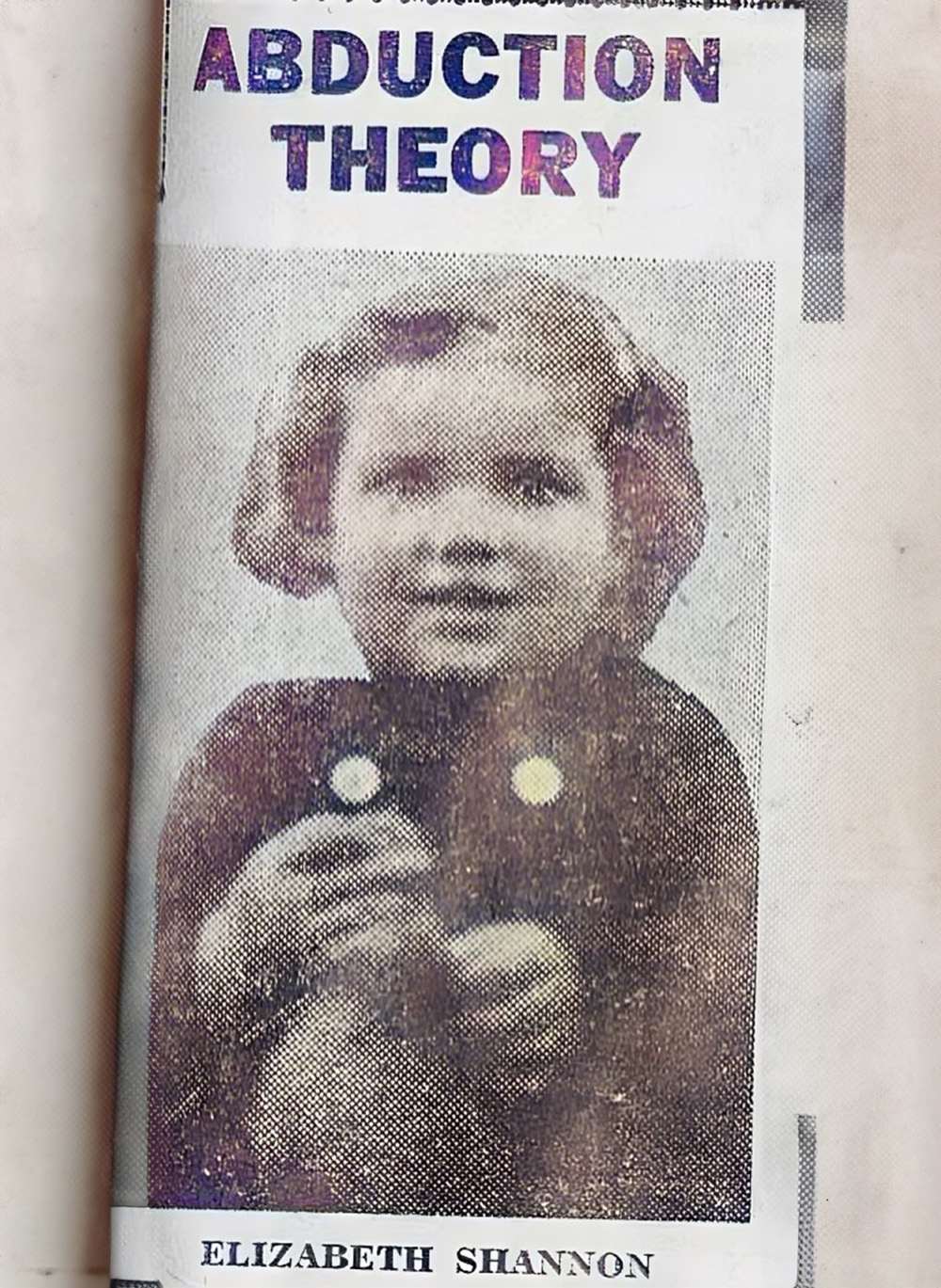

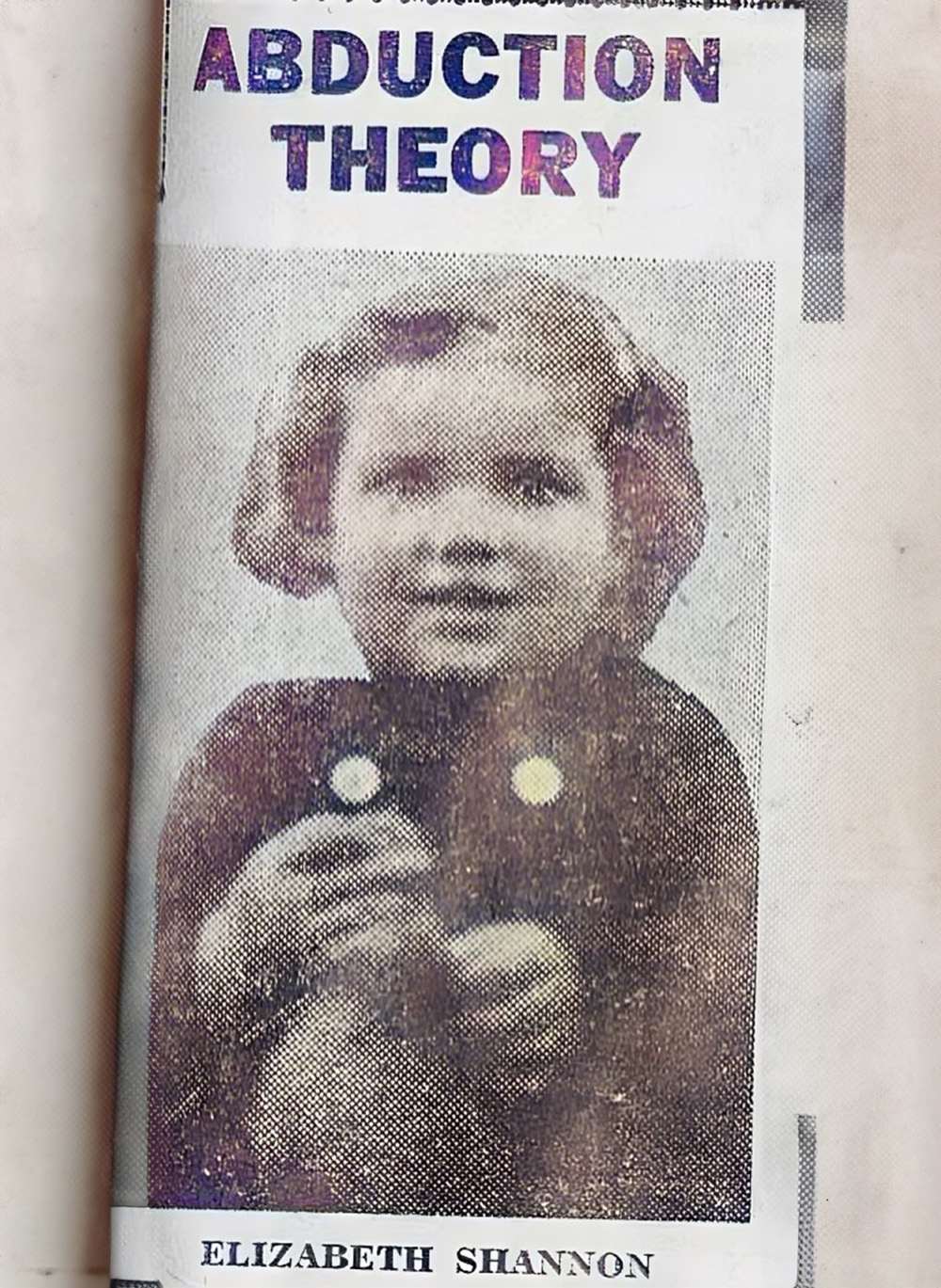

The disappearance generated much interest when I covered it in my second book, Still Missing. I was contacted by a woman who wondered if she might be Elizabeth and forwarded me an old photograph taken when she was a girl aged about seven. The girl had similar hair to Elizabeth and could quite easily have been. The woman explained her earliest memory was being strictly cared for by some official women, and there were often nuns present. After a time, she went into the care of a couple and raised in America where she lives today. Investigating her background led her to a privately run orphanage in Wellington in the 1940s and 50s. She could not find any paperwork and did not even know her birth name leading her to believe adoptions weren’t official and illegal. There had been stories of private adoption organisations in Wellington during this era, but not verified. It was determined the photograph was taken in 1951 and could not have been Elizabeth as she would have been 4, and the girl in the image was older. It’s unlikely Elizabeth would have been snatched and put up for private adoption because there was so much publicity at the time and many people were looking out for her.

Some people recall the case and say it brought out the best in people. Despite being warned to stay off the roads because of the poor weather conditions, many ignored the advice to join the search. Many drove slowly along coastal roads, scouting beachfronts, climbing the bush clad hills weeks after the official search ended. Others not actively involved ensured police and volunteers were regularly provided with hot food and refreshments.

The disappearances of other children like Betty Wharton and Amber-Lee Cruickshank, Douglas Rose, Stephen Franklin, Kirsa Jensen and Mike Beckenridge are household names thanks to the years of publicity they received, whereas Elizabeth Shannon, little girl lost, has largely been forgotten.

David Caldwell died in 2014. When I interviewed him eight years earlier, he was 62, and he could not remember events of November 4, 1949, or anything else about Elizabeth. All he can remember is that something terribly traumatic occurred in his life at an early age. He was 10 years old when he was told the full story.

Aside from the one featured in this article, no other photographs of Elizabeth exist. Her disappearance naturally hit her parents hard, and Bill’s sister Joan recounted occasions when she would find the normally staunch father tucked in a foetal position sobbing uncontrollably. As a means of coping, her parents destroyed all photographs of her, so the tragedy was not a constant reminder.

Bill and Hilda died in 2012 and 2013 respectively. While they had two more children after Terry and went about their lives as best they could, they had 63 years of not knowing whatever happened to their precious daughter. When Hilda passed away, Elizabeth’s birth and disappearance was formally noted at her funeral for the first time.

Years earlier, Elizabeth’s grandmother wrote a heart-rending testament to her beloved Bee in the Shannon family bible. It reads “to my beautiful Elizabeth who went missing on 4 November 1949.’ Beneath she wrote “found …” left blank in the hope she or someone else would one day be able to complete the date she was found. Sadly, after 76 years, this piece of the puzzle has not been completed.

Meanwhile over in Adelaide, the seven-day dig at the property in Adelaide failed to unearth any remains. It did prompt further credible information and identified another site of interest which will be searched in March.

Frank Pangallo, the independent MP who arranged the excavation, remains hopeful the enduring mystery of what happened to the Beaumont children will soon be solved.

For the family of Elizabeth Shannon, no-one knew what her fate was, so it is unlikely her case will receive the same attention.