A River of Grief Runs Through It

17th April 2025

In the April 2005 edition of North & South, 10 years after the Cave Creek disaster, award-winning journalist Mike White interviewed survivors, families and key players in the aftermath and inquiry. He discovered for those affected there was no justice and little healing. Now, ahead of the 30th anniversary of the April 28 tragedy, North & South Digital republishes the story. Photos by Mike White and Tony Ferguson.

By Mike White

Carolyn Smith remembers everything. The stunning view from the top. The platform starting to slide as she walked away. Clutching at flimsy trees as she plummeted 30 metres. Smashing onto rocks. The sickening pain of her fractured ankle, femur and collarbone. The panic and agony of others critically injured in the fall. The bitter breeze sweeping over shattered lives and limbs. Staring up at a circle of sky desperately waiting for help. Watching two of her closest friends die before help arrived. The kiss of autumn sunshine on her face as she was lifted from the chasm at Cave Creek.

She wishes she could forget it all. She wishes she hadn’t lived. “It would have been a hell of a lot easier to end it that way rather than struggle on here. All the time I wish I’d died that day.”

A class photo of the ill-flated 1995 Tai Poutini Polytech outdoor recreation course. Standing (left to right): Leanne Wheeler, Darren Gamble, Clinton Fee, Stacey Mitchell, Jody Davis*, Carolyn Smith, De Anne Reid*, Kit Pawsey*, Matthew Reed*, Paul Chisholm*, Barry Hobson*, Catherine McCarthy*, Scott Murray*, Alison Blackman*, Peter Shaw*. Kneeling (from left): Sam Lucas, Mark Traynor, Evan Stuart*, Stephen Hannen, Anne-Marie Cook*, Abram Larmour*.

*Died at Cave Creek

Eighteen people were on the Cave Creek viewing platform on Friday April 28 1995, when its overstressed nails finally tore free and the shoddily built structure slipped from the cliff. Fourteen died. Smith and others somehow survived. It was miraculous and, beyond belief in religious deliverance, the only explanation people can come up with is luck.

But for Smith, now 28, there’s nothing lucky about her survival. What happened on the West Coast that day has quite simply ruined her life.

When the physical scars healed the terrible mood changes set in. “I’d just lose it at anything, burst out crying, but if you asked me why, I wouldn’t have any idea.”

Her mind and memory would torture her, making her replay the ghastly sequence of events from sunny start to frightening finish. Determined to deal with her demons, she left the Coast and put Cave Creek behind her for a while. But gradually it all filtered back and two years ago she had a mental breakdown, shifted back to her mum’s place near Greymouth and asked for help.

“Anti-depressants have partly arrested her psychological slide but they can’t stop the nightmares. “Terrible dreams, full of anger. I’m often waking mum up shouting, cursing my head off, punching the wall in the night.”

The days aren’t much better. “Before Cave Creek I’d sit on the porch and look around the valley on a beautiful sunny morning and absolutely fall in love with the place every day. Now I look at it and I just see hills.”

Carolyn Smith survived Cave Creek but wishes she’d died. She now calls herself Kelly because the disaster destroyed the person she once was.

Smith’s hands and feet tremble faintly as she teases tobacco from a Park Drive packet and crafts it into a cigarette, thumbing her lighter repeatedly before dragging deeply. “The other part is the anger of how it destroyed who I was. I look back and think if that day hadn’t happened where would my life be now? I’d still have some of those beautiful people as my best friends. I could have been doing anything.”

The greenstone teardrop pendant given to survivors and victims’ families by the Greymouth polytech she was at, still hangs round her neck as a talisman of that dreadful day and the friends she lost.

Meeting Smith now she introduces herself as Kelly. “People who knew me before still call me Carolyn and I don’t mind that. But as far as I’m concerned the person who was Carolyn died that day and there’s someone else that’s come through and I’ve just had to learn to live with that person. I consider myself Kelly now.”

On April 28 a small group will gather at Punakaiki to unveil a special book for viewing at the DOC visitor centre containing family memories of those who died. Then they’ll quietly travel the 10km to Cave Creek to commemorate the 10th anniversary of one of this country’s worst disasters.

Cave Creek has become threaded into the tapestry of New Zeeland tragedy resting alongside sorrowful names like Tangiwai, Wahine and Erebus. The death toll was fewer at Cave Creek but its impact on the country’s psyche, our attitude to the outdoors and public safety, has undoubtedly been more far reaching than any of the others.

After the disaster, a Commission of Inquiry was quickly convened to investigate what happened that day when an outdoor recreation class from Greymouth’s Tai Poutini Polytech walked onto the platform. Long before Judge Graeme Noble’s controversial findings were released, the country knew the incredible and horrifying details.

The platform had been planned by amateurs and built on a working bee by DOC staff who didn’t take the plan with them. The structure had no input from a carpenter let alone an engineer, had no consents and failed to comply with even basic construction rules. As one grieving father described it so succinctly, it was quite simply a booby trap.

The failures were staggering, the collapse of communication between DOC’s different levels impossible to believe, the results catastrophic.

But after a $2 million, five week hearing, Judge Noble ruled nobody was responsible. Instead he blamed the disaster on “systemic failure” within DOC caused largely by underfunding. Despite ample evidence of human negligence he effectively exonerated all those involved, from the jacks-of-all-trades who knocked up the platform to the head office bureaucrats who huddled for cover. Three further government or DOC reviews failed to find any individuals responsible.

West Coast conservator Bruce Watson was the most senior DOC official to resign, quitting in an act of personal contrition. The following year Conservation minister Denis Marshall stepped down from his portfolio but remained in Cabinet, finally retiring from Parliament in 1999. DOC director general Bill Mansfield was cleared by a State Services Commission inquiry and refused to quit. He was eventually pushed from the job in May 1997 after new Conservation minister Nick Smith told him DOC couldn’t progress while he was at the helm. (Smith is insistent both Marshall and Mansfield should have stepped down much earlier for the sake of the familles and state service.)

In a separate investigation, Christchurch police recommended several DOC staff should face charges, including manslaughter. Incredibly, a crucial report was lost and eventually a decision was made not to prosecute.

Those involved slipped away, some from their jobs and most from the Coast. For the families and survivors, moving on from the horrors of Cave Creek was nowhere near as easy. For most, there’s little closure, no escape, everything’s just as raw and painful as it was a decade ago.

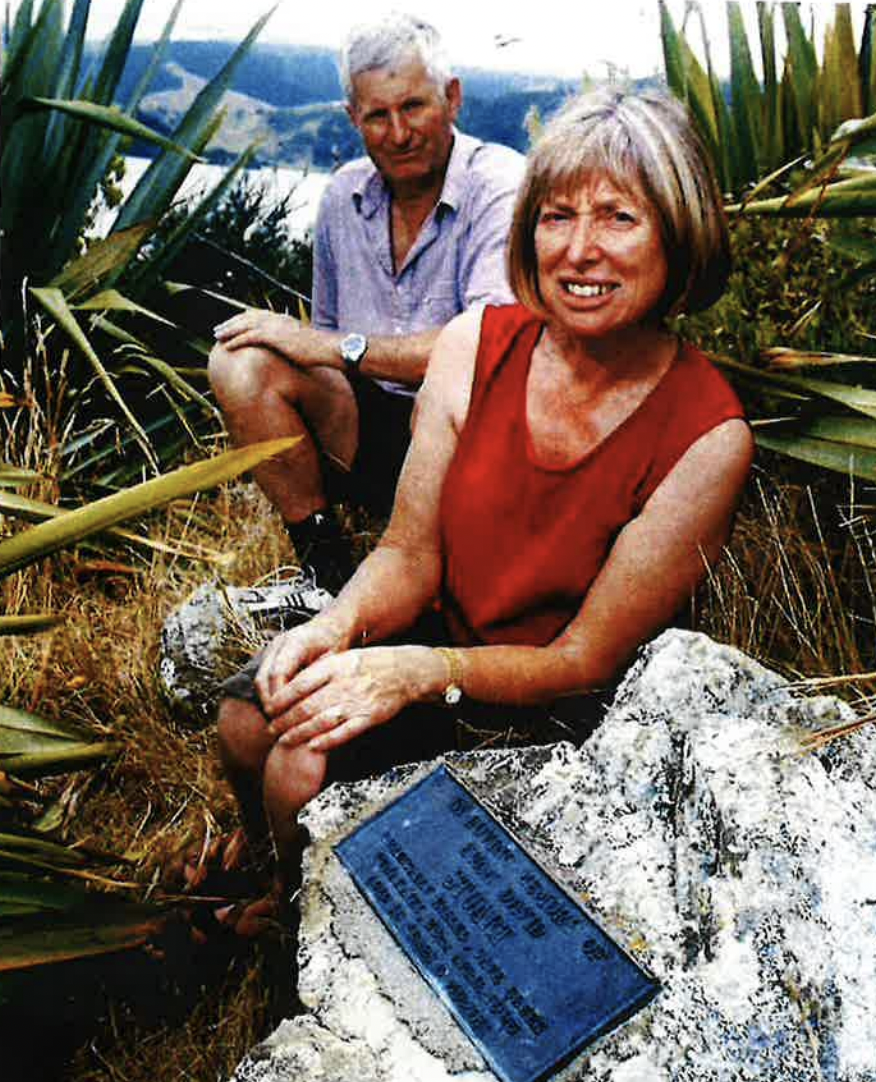

Virginia and Harry Pawsey and their daughter Fleur, whose son and brother Kit Pawsey died at Cave Creek in 1995.

***

Just north of the Pancake Rocks on SH1, past flax-fringed views of sweeping surf and signs for whitebait sandwiches you’Il see the turn-off for Cave Creek. It’s a slow drive twisting up a shingle road that becomes a stream when it rains. Bush-draped limestone cliffs fall sheer into flax swamps. It’s the kind of place where you’re sure extinct creatures might still be secreted. From a bowed Taranaki gate you have to walk the last couple of kilometres to Cave Creek itself, through fields of browned summer growth, gossamer spider cocoons and industrious bees. Cicadas trill from an amphitheatre of peeling manuka.

Where the track splits there’s a monument, a metre high boulder covered in lichen, moss and a plaque naming the victims. A small pile of stones has been left at its base and two artificial roses are tucked behind the plaque.

Walk on another 15 minutes and you can spy through regenerating scrub where the platform was. Two pile holes in the earth’s mossy edge are the only sign of what was once there. It seems a lot further than 30 metres when you glance over the edge – it’s staggering anyone survived. A rockfall from the surrounding cliffs has engulfed the area where the victims came to rest, a single punga curving skywards, fronds unfurled, splashing colour amidst the grey chasm.

At the bottom the temperature dips like an ocean thermocline. A robin, which some of the families see as a spirit of their children, flits close following every footfall.

For some though nothing can bring peace. Marjorie Shaw wishes she’d never run into the friend who one day told her about the Greymouth outdoor recreation course. She wishes she’d never mentioned it to her son Peter or encouraged him to do it. He might be alive today.

Ten years hasn’t healed anything. “It’s devastated our family. Every time I hear the name DOC I still get angry. They all got away with killing my son.”

After Peter died Marjorie’s husband Andrew lost interest in his Wairoa helicopter business, sold up and they moved to a Manawatu farm to start life anew. In January 2001 Andrew was killed when his helicopter crashed on Wellington’s Mt Victoria. Marjorie was left to face another inquiry (four years on there still hasn’t been a Coroner’s hearing into Andrew’s death) and suddenly she had to shoulder the Cave Creek burden alone. Her daughter Rachel went to live in Canada where she doesn’t have to constantly face the tragedy.

Shaw isn’t alone in her feelings that Cave Creek will never be properly resolved because nobody was ever made accountable even though the law had clearly been broken. It’s not a witch hunt, not a thirst for revenge, she insists: “But prosecutions should’ve taken place. If people had been found innocent, fine, we would’ve accepted that but it should’ve been left to the courts. We just wanted them to stand up and prove they weren’t responsible.”

She believes everyone from DOC staff who nailed the platform together – ignoring plans, the need for bolts and neglecting to attach the structure to a concrete counterweight – right through to DOC’s then director general, Bill Mansfield, and Conservation minister Denis Marshall were culpable and should have accepted that.

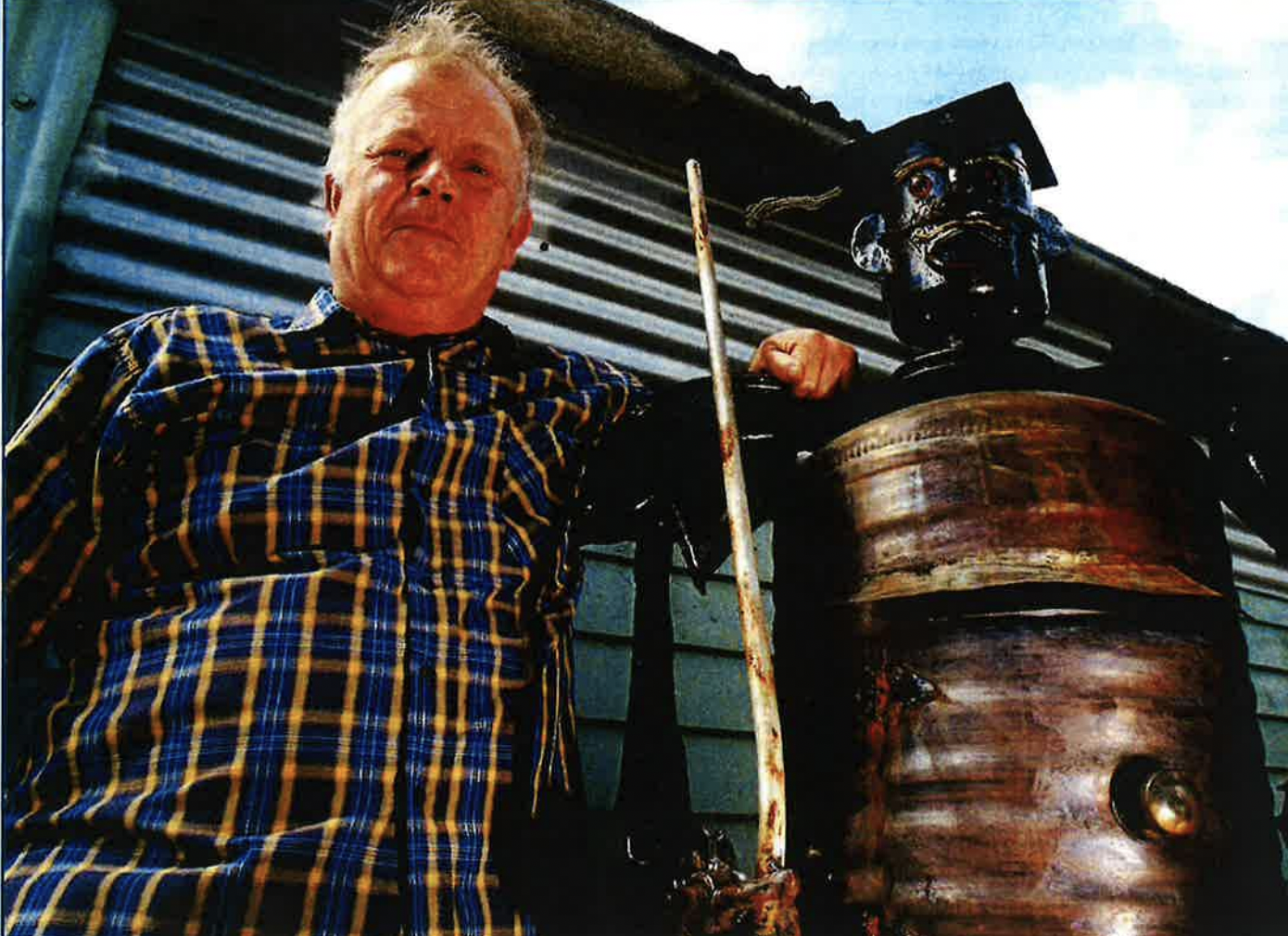

Andrew McCarthy, who lost his daughter Catherine, when the platform collapsed.

They killed 14 people through negligence and scarred a lot of others, damaged a lot of people’s lives. And the people responsible just got away with it — literally walked away scot-free. There was no justice. I just hope none of them have the audacity to turn up to the 10th anniversary.

The appointment of Noble, an earnest but hardly eminent Christchurch District Court judge, jarred compared with the choice of Justice Peter Mahon, one of the country’s top legal minds who headed the Erebus inquiry.

“Why weren’t our kids worth that?” demands Shaw.

In her view, Cave Creek was so damaging to DOC and the government that it was buried like the bolts used to secure the doomed platform (these weren’t used at the time of construction because the builders didn’t have a drill and the bolts were later unearthed where they’d been discarded in scrub by the cliff face). And because of that, she says, moving on is virtually impossible.

“You never get over losing your child. You might come to terms with being widowed but your child’s not supposed to die before you. It’s ruined my life. I just have to try and make good with what I’ve got left.”

She’s one of many left struggling.

In the hustle of Wellington’s Lambton Quay Rod Davis stands out from the suits in his untucked shirt, casual trousers and tousled hair. He lost his 18-year-old son Jody at Cave Creek and every time he passes former DOC head Bill Mansfield on the capital’s main street it brings it all back.

Mansfield (who refused to be interviewed for this story) never looks at him despite having met him after the tragedy.

Mind you, DOC managers had a habit of doing the wrong thing when dealing with Davis after Cave Creek. Just after the platform collapse a senior DOC official visited Davis and as he sat on a chair, the leg broke. “He said, ‘Oh, we don’t need another Cave Creek’ — and expected me to laugh.”

Now an advocate with the Children’s Commissioner, Davis deals with kids who’ve had a rough ride from the system and all the time wonders how his boy would have turned out. “I’d have a 28-year-old son this year. All those opportunities, all those possibilities …”

Jody had a gecko tattooed on his arm, reflecting his love of rock climbing. Davis, who raised Jody largely as a solo dad, had the same done on his shoulder after Cave Creek. He says he could almost understand if Jody had died mountaineering or kayaking — but not in such a senseless way — on a shonky, illegal platform being lectured about geology. “That whole clichéd thing that they died doing what they loved was rubbish — they were bored shitless.”

Talking about Cave Creek comes easily to Davis. It’s how he’s dealt with things. But it’s not helped overcome his boiling bitterness towards DOC and those he believes got away with causing Jody’s death. In his eyes, Cave Creek wasn’t an accident — it was an appallingly planned and built structure. And human beings, not amorphous systems, were responsible. “They all ended up blaming others and it went round and round — that was so frustrating. The more that came out about what people did you couldn’t help but go back into incredible depths of anger and the forgiveness gets pushed right out the door. I’m absolutely miles away from forgiving any of those people. Nothing’s been done in those 10 years to earn it.

“It really upset me when DOC said, ‘We don’t want this to happen again.’ You’re supposed to buy into this pot pourri of humanity and you’ve just lost your child. So what does that mean — that our kids were guinea pigs?”

Like other parents and survivors, Davis will be at Cave Creek on April 28. “Ten years is a road sign. And you wonder what we can hold out for in the next 10 years — and I guess it’s just that you heal a little better.”

***

Ian and Barbara Stuart buried their son Evan’s ashes on their Nelson farm overlooking the bay where he loved to fish.

A cello’s mournful melody drifts down the corridor as Linda O’Dea describes her last decade. She manages the Christchurch Music Centre, a Victorian nunnery converted into space for artists. Her son Stephen had just started as DOC’s field centre manager at Punakaiki in April 1995. He died with the students, leaving behind a son Sam, who turned eight the day after Cave Creek.

O’Dea slides a photo from her diary, of Stepen, taken two months before he died, standing by Franz Josef glacier having just waded through its salty waters, his bearded face beaming.

She misses the phone calls out of the blue, his descriptions of how beautiful the Coast was, his wicked humour that once saw him confiscate whitebaiters’ nets, auction them back to their owners and donate the proceeds to the local school. “I always think he’s just here,” she says pointing to her shoulder, eyes welling, voice fading.

In the immediate aftermath alcohol became a refuge — to help her sleep as much as anything, to escape the constant headlines.

Her husband Jim, died last year, seething to the end, a state of mind O‘Dea is certain hastened his death. She sees anger as an empty emotion but there’s one thing that would have helped her cope much better. “I would have liked people involved to step up and say, yes. I did things wrong. If they’d said ‘I’m responsible and I apologise’, it would have gone a long way.”

It’s something the victims’ parents repeat over and over. Bill Mansfield visited each family after the disaster and Coast conservator Bruce Watson spoke to them before he quit. But beyond that apologies have been rare.

North & South contacted nearly all the DOC staff directly involved with the platform collapse. Some declined to comment. Several simply hung up. Former Punakaiki field centre manager Craig Murdoch intemperately snapped that we should “move on”.

Move on. Get on with life. Put it on the shelf. Barbara and Ian Stuart have heard these platitudes time and again. Photos of their good-lool‹ing son Evan decorate their home near Nelson. In an album there’s a special photo — one that arrived seven months after he died. It was taken by fellow victim Abram Larmour about an hour before they died and eventually retrieved from his camera. The polytech van had got stuck on the way and the students are pictured coaxing it out. Evan’s there, smiling, waving. Barbara and Ian see it as him saying goodbye for the last time.

But it doesn’t draw any final curtain over the incident or the gap Evan left. “You learn to live with it but you never get over it. You always miss the person — we’re an incomplete family. I always said I was going to shed a swimming pool of tears for my son — and I haven’t filled it yet,” says Barbara.

Ian, with seed-flecked socks and straightforward attitude, tried to cope by farming harder but the typical Kiwi male reaction of bottling emotions was no defence. “It was painful and it’s still painful when the subject comes up. I suppose that’ll always be the way. Every anniversary is rugged. It’s a mark on the calendar of our lives.”

Barbara describes the last decade as a journey to acceptance. “What happened isn’t something you can put a lid on and forget. We were always adamant we wouldn’t let it ruin the rest of our lives. But some days it’s been hard work.”

Stephen Hannen’s remarkable survival despite horrendous injuries made him a symbol of Cave Creek.

Harry and Virginia Pawsey have been hearing they should move on ever since son Kit died. The North Canterbury farmers became unlikely spokespeople for the affected families in the wake of Cave Creek and are still the ones who link the relatives, liaise with DOC and organise annual anniversary gatherings on the Coast.

Even when North & South reviewed the Cave Creek case in May 1996 there were calls for the parents to move on. Conservation minister Denis Marshall commented: “Others suffer similar tragedies and one doesn’t see quite the same continued … unhappiness. I’m sure it’s the case that parents still feel the accountability issue has not been resolved but I think it’s rather sad.”

Such appalling insensitivity may have been one of the factors that pushed the families to pursue compensation and law changes.

The Crown paid nearly $3 million to the families and survivors after they’d threatened to sue for exemplary damages (most affected parties received just over $20,000). In 2002 legislation was passed allowing Crown entities to be prosecuted for breaches of the Building and Health and Safety in Employment Acts — plugging a previous gap that meant DOC couldn’t be charged for not obtaining consents for the Cave Creek platform. And the same year the government voted an extra $349 million for DOC to maintain facilities.

For Virginia Pawsey, the changes offered overdue comfort. “I like to think some of the money has gone to forests and preservation of species and it makes it better that I can think, this is Kit’s legacy to New Zealand. Any parent who loses a child wants it to mean something, not be forgotten, not be for nothing. You want improvements to life to come out of it.”

However, she too is left with the rankling injustice that Judge Noble found no DOC staff were negligent. “That’s where the law is an ass because they did fall below any acceptable standard of care. I wanted that inquiry to say those guys cocked up — they really stuffed up. You got the feeling some of them weren’t remorseful. They could have come to us individually and it would have meant a huge lot.”

Harry Pawsey was most angered over attempts by government and DOC managers to blame everything on a bunch of larrikin Coast DOC workers while people like Mansfield hid behind “defensive bureaucratese and high-flown crap” rather than resigning. For their only other child, 25-year-old Fleur, Kit’s death had an ironic counter-effect. Rather than scaring her off the outdoors she pursued her brother’s passions. In February she was second in the women’s two-day Coast to Coast event.

The race scratches and grazes are still evident — just like the wounds of losing a brother. Fleur often imagines the dreadlocked Kit holding her up when kayaking rapids. And memories surface during training runs in the Tararuas. “You get a bit annoyed when you go past a DOC sign and see 10 bolts holding it up and the sign’s more solid than the platform was.”

When DOC engaged slick, erudite Hugh Rennie QC to represent it at the Commission of Inquiry, the victims’ families and survivors grouped behind Christchurch lawyer Grant Cameron. It was a clash of styles and views.

Cameron is a pugnacious battler with a raspy edge to his voice. Ten years a cop, 25 years a lawyer, he’s had some big cases (the Renshaw Edwards fraud, Lake Alice patients claim) and big wins. Cave Creek was more like a draw. He represented the families’ views ferociously and eventually negotiated what he considers fair compensation. But he was bitterly disappointed by the commission’s ultimate finding.

“Judge Noble decreed there hadn’t been any negligence and it was systemic failure. I think that’s utterly wrong — the evidence of negligence is overwhelming.”

In his central Christchurch office, blinds pulled down, trouser legs tugged up and collar loosened to counter mugginess, Cameron’s belief that justice was warped in the Cave Creek case clearly hasn’t cooled in a decade.

“It’s not possible to blame a system. Systems don’t design themselves, maintain themselves, change themselves. It’s a case of human act or omission that resulted in the calamity we had. Every time l hear those words, ‘systemic failure’, I wince because it’s become the ultimate cop-out. It’s just a convenient phrase trotted out by those who need to point the finger in another direction.”

Even though Noble didn’t find breaches of due care by DOC staff, Cameron was sure numerous workers and managers would face charges, including manslaughter, following a parallel police investigation.

That almost happened. The extensive police file was reviewed by Christchurch Detective Inspector Kevin Burrowes who handed his recommendations to a police legal adviser. They agreed charges should be laid against a number of DOC staff and his report was sent to Police Headquarters, the Crown Law Office and Solicitor General.

Bizarrely, the report went missing and has never re-emerged. Even more bizarrely, Burrowes insists there was only one copy of the report and he can’t remember the number, let alone the names, of DOC staff on the list recommended for charging. In 1996 it was announced no charges would be laid.

Cameron, who plans to write a book on Cave Creek “one day”, remains unconvinced the report was innocently lost. “I’m not into conspiracy theories but on a reasonable balance of probabilities would the police have taken due care of a critical document like that? I spent 10 years in the police service and I can say with some authority they’d take considerable care.”

Cameron suspects the report may have been deliberately mislaid because the issue was so sensitive, with the government and public service nauseous about DOC staff facing the courts. He believes a copy still exists somewhere and will surface one day.

Compounding his concern is that when the document went missing Burrowes wasn’t interviewed to recreate its contents. Nor was another officer asked to form a fresh opinion. The police, Crown Law Office or Solicitor General could all have ensured the legal process continued. But suddenly it was decided no charges were to be laid.

“I utterly expected the law to take its course. It’s stretching credibility to think the sequence of events was simply a coincidence. More likely it was a case of influence peddling and meddling and people either did the wrong thing or failed to do the right thing. Why didn’t public servants face the wrath of the law? If that event had happened on a building site the police would’ve laid charges within three weeks.”

Kevin Burrowes, whose report went missing, doesn’t buy into the theory the document was destroyed deliberately. “God knows what happened to it.”

However he did think charges would be laid and understands how the victims’ families feel the case was never resolved.

Bob Gregory also understands how Cave Creek’s wounds are still raw for many. Victoria University’s School of Government associate professor, he lectures about the tragedy and remains outraged people seemed to act more from self-interest than public interest. “Justice hasn’t been done, hasn’t been seen to be done and for many there’s been no closure.”

He labels Judge Noble’s blaming of the system, “ridiculous and nonsensical. People were directly culpable — it didn’t happen on its own. Underfunding of DOC had nothing to do with it.”

Gregory is critical of Marshall and particularly Mansfield, who went on to a stellar international legal career after DOC and very effectively preserved his reputation while families suffered for lack of someone taking responsibility. “There are elements of Cave Creek that smack of the old boys’ network protecting its own.”

And he wonders how differently things would have panned out if it had been a class of well-connected, well-heeled law students that plunged to devastation. “Or what say a group of wealthy Americans, given their litigious society and expectations. What would have happened to the Burrowes report? What would the Crown Law Office have done then?”

Up to nine DOC employees potentially faced charges. Few were as intimately involved as Kevan Wilde, DOC’s former northern operations manager on the Coast. He prepared the initial viewing platform concept, helped choose the site, approved the plans and orders for materials and was one of four staff who helped build the platform in April 1993.

For the first two years after the tragedy he couldn’t speak about it without shaking and becoming ill. The trauma led to deep depression requiring intense counselling. He quit DOC several months after the disaster without a job to go to and remained unemployed for some time. The former policeman and park ranger had always protected life and helped people in the outdoors and “the idea I was involved in something causing so much death, grief and pain was extremely abhorrent and disturbing”.

So too was seeing the distress and devastation of the families and other staff. “It’s something I’ll never fully recover or move on from. Who could? But none of the effects on me amount to anything compared to the trauma, pain and grief that I can only imagine was and still is being experienced by the survivors and victims’ families. I’m profoundly and extremely sorry the tragedy ever occurred and again offer my ongoing and deepest sympathy as well as my most heartfelt and sincere apologies.”

Former West Coast conservator Bruce Watson has never regretted resigning in December 1995 as a gesture of reconciliation. He believes it would have helped the families if more senior DOC managers had done likewise but feels there was a definite move to make Coast staff scapegoats. Watson now runs a bookshop in Hokitika with his wife and does conservation consultancy.

Far from wanting to bury Cave Creek he thinks the 10th anniversary is a good time to reflect on what’s been learned. “I think about it just about every day. It’s the saddest event of my life. There’s always a danger in not remembering, in case mistakes get repeated.”

Rescuers at the scene of Cave Creek. By Tony Ferguson.

Les Van Dijk was the DOC worker who drew up the platform plans and pre-built the deck before it was lifted to the site. He was also one of the first people to arrive after the collapse to tend to the broken and dying victims. Ironically, although Van Dijk’s design probably wouldn’t have gained a building consent, the platform would still be there if the steel he’d put in the plan and purchased (but which mysteriously went missing) had been used to attach the platform to its concrete counterweight.

Van Dijk still lives on the Coast, still works for DOC. His voice wavers and he breathes deeply to get through each sentence. He’s haunted by the memories and time hasn’t soothed that.

“It’s always tough. You live with it every day. Every day you wish the clock could be rolled back. I really feel for all those involved, obviously the families, but all those people it’s affected — the survivors — it must be pretty difficult for them at times. It’s pretty devastating to me. Always will be. But there’s not a thing you can do about it — just live with it.”

Van Dijk lives just a few kilometres from one victim’s father, Andrew McCarthy, a charmingly quirky science teacher who catches bugs from the windows of his Runanga house with a butterfly net and recites their Latin names as he releases them outside.

McCarthy, who lost 17-year-old Catherine, is one of the parents who’s gone furthest along the road to acceptance about Cave Creek . “I’m not exactly at peace — it just is.”

He wanted Denis Marshall to resign earlier, but never wanted local DOC staff to be punished.

After Van Dijk spent a harrowing day on the Commission of Inquiry stand, McCarthy took him down to the Rapahoe pub for a few beers, to show locals he considered him innocent. lt was the same pub McCarthy used to take Catherine and have jug races — her with raspberry and coke, him with beer.

McCarthy puts on slippers and with a soft, clipped English accent that belies his 50 years in New Zealand beckons me to follow him through the house. There are pictures of Catherine at her school ball, photos of wild places she loved, another with all 14 victims’ bright faces smiling from it.

Outside, beside the three-tonne pile of coal used to ward off West Coast winters, there’s her handprint, forever set in the concrete floor of the garage she helped her father build. The irony that the garage never had a building consent isn’t lost on McCarthy.

But he knows a bit about buildings. In his physics classes he teaches about Cave Creek and has built a balsa-wood scale model of the platform. He gradually places cigarette lighters on the structure — each lighter equating to two people — until it topples. McCarthy also has examples of different ways of attaching the deck to the piles, from the tragic nailing through to notching and bolting. It’s part compelling real-life education — part a personal coping process.

He’s scarred by what happened but it’s a flexible, philosophical scar. “Accidents do happen — end of story. And it was an accident. Life is full of chances and sometimes they go wrong. You learn to keep it in perspective — the cicadas keep on singing.”

***

Summer’s cicadas do keep on singing but for Carolyn Smith the tune is now discordant. The bush has been spoiled for her, a source of anger not sanctuary. She once wanted to work for DOC, now she hates the organisation.

Tenderly fingering Carolyn’s photo, her 72-year-old father Alan is bleached by bitterness that her life and career have been ruined. “Instead of working, being an outdoor girl and doing what she really loved, she’s off work with stress. It really does hurt. At least the ones that are gone are at peace.”

Cuddling Cracker, her bull terrier, Caroyln says Cave Creek’s four survivors have largely been forgotten, their struggles swamped by the politics of the disaster.

Of the others, Stacy Mitchell is a carpenter in Gore but hasn’t spoken publicly about Cave Creek for nine years. Sam Lucas has spent most of the last decade as a student and is currently completing a PhD in physical education at Otago University. He rejoined the Tai Poutini Polytech course after three months and has done several Coast to Coasts despite a dodgy knee. While this and many other things constantly take him back to that day, Lucas has packed loads into life since then.

“It’s part of who I am, I guess. That fall was just one day out of your life and it doesn’t define me as a person. It’s not who I am. I’m not a Cave Creek survivor — I’m Sam Lucas and that’s something that happened.”

And lastly there’s Stephen Hannen, who in many ways became the symbol of Cave Creek. The former New Zealand age group volleyball rep had just turned 19 when the Cave Creek platform went down. He broke his spine, smashed his jaw and 16 other bones, had both lungs collapse, survived blood clots on his brain, a ruptured bowel and two cardiac arrests. Doctors gave him a 10 percent chance of living.

It took nine weeks in intensive care and a year at Burwood’s spinal unit for Hannen to prove them wrong. At his worst the six-foot-seven, 90kg Hannen had shrunk to 45kg. Sedatives spirited bad hallucinations into his gashed head and he’d wake desperate and anxious, wishing he’d died. “I couldn’t get out of my body. I was just trapped and couldn’t move and there didn’t seem to be any light at the end of the tunnel.”

Today he’s just like any other young guy, streaked hair, jeans, choker necklace, Oakley shades — and a $10,000 titanium wheelchair. A tetraplegic, Hannen has feeling from his chest up, limited arm movement and a heart as big as they come. He’s a member of the New Zealand wheelchair rugby squad and was a non-travelling reserve for the Wheel Blacks who took gold at last year’s Athens Paralympics.

He runs a storage business as well as doing graphic design work and owns a new house on Christchurch’s prim northern fringes. He drives a Subaru Outlook, goes skiing, sea-biscuiting, plays tennis, has done a bungy and skydived.

He married Sabrina Rammelt in 2001 but they separated six months ago, something Hannen admits was tough. But having got through Cave Creek he knew he could handle it.

You could look at Hannen and think he’s either lucky to be alive or damn unlucky to have ended up in a wheelchair. But Hannen’s in no doubt. “You can’t look at the past and think ‘what if’ or ‘what would I have been doing’ — that’s not reality. Life before Cave Creek is almost a dream –— walking around, playing sport, the outdoors. And now this is normal. This is the way life is. And it’s great. I don’t have any down days, it’s all good.”

Hannen says family and friends have been crucial and so has his Christianity, which has been a real strength since Sabrina left.

“You don’t focus on the 1000 things you can’t do anymore, there’s 9000 things you can still do. The big thing is what you make of life, being positive and I’m making a good life for myself. Life’s for living — not for living in the past.”

Poem, by Sam Moynihan O’Dea

(who turned eight the day after the Cave Creek platform collapse killed his father Stephen O’Dea).

My Dad

My Dad will give me love for my birthday. My Dad will be happy he died quickly and he won’t have to be in a wheelchair or in a hospital. He‘s in heaven now and he will be tramping in the bush and he won’t get lost.

My Dad loved the bush and tramping and he loved fishing too.

He was good. He did lots of good things, like helping people.

He took me fishing all the time and he took me on bush walks and we stayed in huts. I am very sad.

He knows how to make huts out of sticks and inside would be a good possie to Iight a fire, but he said we’d better not as it’s not safe.

Sometimes we caught fish and sometimes we didn’t get any.

My Dad bought heaps of good birthday presents, he bought me my own sleeping bag. Dad taught me heaps of things about the bush. My Dad will be watching me all the time.