Catherine Chidgey in conversation with North & South

8th May 2025

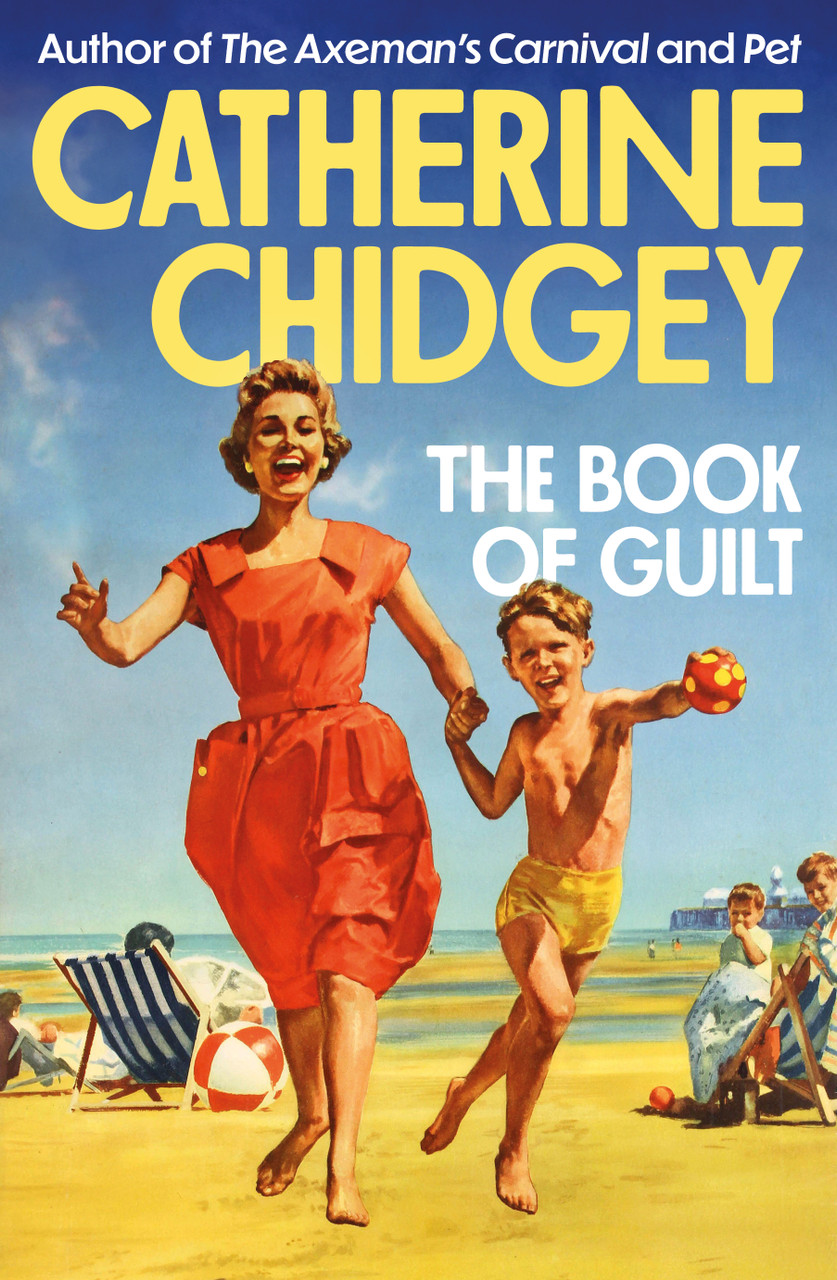

Internationally lauded and best-selling Aotearoa author, Catherine Chidgey, has published her ninth novel, The Book of Guilt. Set in Britain in 1979, it’s a dystopian and sinister story about 13-year-old triplets – Vincent, Lawrence and William – who live in the New Forest home, part of the government’s Sycamore Scheme. After an international bidding war The Book of Guilt was picked up by UK publisher John Murray, who was established in the 1700s and has published, among others, Darwin, Arthur Conan Doyle and Jane Austen. Sarah Daniell caught up with Chidgey on the eve of the book’s launch, to discuss work, words, family and death – and the ‘difficult child’, Tama, the omnipotent magpie star of her novel, The Axeman’s Carnival.

By Sarah Daniell

North & South: I feel I must ask – how’s Tama?

Catherine Chidgey: He’s furious. He’s absolutely livid at other books taking the attention away from his book. Yeah, he’s not impressed. We’ve just moved house. And basically that was because he trashed the old place. You don’t want to know what state he left it in. So we had to move. Didn’t tell him our new address, but he’s tracked us down. And is bashing at the windows at all hours. It’s pretty ugly.

N&S: What a thug. I mean, he really needs to do some work.

CC: It just never ends. Well, maybe he’d feel a bit placated if I did get like a gigantic painting of a magpie and hung it on the wall. He wouldn’t destroy that.

N&S: You could have a mural done on the outside of the house.

CC: That’s tasteful.

N&S: The last time we spoke, we were at the Auckland Writers’ Festival discussing whether AI could write a novel. Do you feel less or more wary about AI these days?

CC: I mean, it’s moving so fast. And I did see on social media that someone had posted this short story that was done using an AI tool developed specifically to produce literary fiction. And it had produced this short story that was actually quite beautiful. It was really well written. And that rattled me a bit, I have to say.

N&S: AI could not have created Tama though, surely. Possibly could do your research? On that, particularly with The Book of Guilt, where do you start and how long does that process take?

CC: I do read everything I can get my hands on about the topics that are driving the book. And I do read voraciously before I start writing. But as a rule, I tend to dive in and start the writing before I know everything I think I need to know because otherwise I would never actually start the book. So it does go in tandem with the writing and often if I don’t know the answer to a particular research question, I’ll just leave XXXX in the manuscript at that point and bold it so that I know when I come back to it that, oh yes, that’s a research question I have to answer. I do really love the unexpected gifts that research drops into my lap, finding things that I never knew were important to the book, but which end up being very important to the book or which end up being central symbols somehow.

With The Book of Guilt, I knew that I wanted this set of children’s encyclopaedias to comprise the full library for the boys [in the New Forest home]. And I wanted it to be based on a real set of encyclopaedias. And so I was looking at different ones that were around in the 1940s and 50s because I wanted it to be a little bit outdated too.

And I found the Book of Knowledge, but I couldn’t get hold of it very easily in New Zealand … I needed the whole set. It was when I started looking on Trade Me, I just thought, well, I’ll see. I mean, I know it’s a UK thing, but maybe it somehow found its way here as well.

And I found a set for $20 … $20! … that a lovely man in Auckland who’d grown up in England was selling. And it had been his set of encyclopaedias when he was a boy. And he was just having a big clear out and he was delighted that I was going to take it and give it a really good home.

And so it was when I was looking through that set that I realised, well, there’s a foldout map of the world in here and it has two New Zealands at either end of the map. The book has nothing to do with New Zealand at all, but I just love that there was that little kind of nod to my origins. And also the way that it allows me to talk about some of the things that go on in the book, which I can’t really talk too much about because it’ll be spoilers.

But that there are these two identical places and we’re talking about identical triplets here that just really got under my skin. And that’s the kind of gift of research that I mean, when something like that presents itself to you and you go, oh right, that’s what I’ve been actually looking for all this time. And here it is, it’s finally found its way to me.

There’s something kind of magical about it and mysterious about that process. And it’s wonderful when it happens. So I become quite addicted to those moments and become obsessed with reading everything I can.

N&S: Nostalgia, wholesomeness, – they’re sitting ducks for manipulation into the menacing?

CC: Around the late 1970s Britain, and the TV shows that were playing at that time and the kinds of sweets that you would have bought in the corner shop at that time, and the clothes that children would have worn and the politics of that era – even though I changed that – I wanted to map the story really closely to the real world so that readers will then buy into this alternative reality that I’m creating, or this sort of slightly skewed reality that I’m creating. And so the research is a way of underpinning all that.

It’s an interesting year in terms of contrasting with those encyclopaedias, which are so wholesome.

N&S: It gave me Enid Blyton vibes with the bright colours and the food, the little sandwiches.

CC: I absolutely devoured Enid Blyton and it was at the time, maybe you remember this too, when she was very much frowned upon and she’d been whipped out of the public libraries, but we still had her in our school library.

And I can still remember those sort of red bound, thick paged editions that were probably from the 50s that we had in our school library. So I absolutely loved those. And I particularly loved The Magic Faraway Tree and The Wishing Tree and all of those ones as a younger child, but I remember being a little bit older and reading her Naughtiest Girl in the School, boarding school books.

And I branched out from there to reading every boarding school novel that I could get my hands on. I still have quite a lot of them of those old sort of 40s and 50s school girls stories.

There was something really attractive to me about being part of an institution like a boarding school. I have friends who went to boarding school in real life and said they hated it, ‘the worst time of my life’. But those books kind of made it seem magical and like you were part of a special club and you could have these midnight feasts and you could earn badges.

And it just seemed, you know, kind of a world away from suburban Lower Hutt in the 1970s. The girls in those stories had a whole lot more agency.

So those books have stuck with me and I’m starting to read some of them together with Alice, my daughter, who’s about to turn 10 and hoping that she’ll take to them as well. I don’t know, it will be interesting to revisit them and see just how dodgy they are now.

The Secret Garden, we’ve just had that experience reading that again, with Alice. I haven’t read it for years but loved it as a child. It was that kind of very antiquated language and also quite questionable attitudes around racism and yeah, which would never get past the editor now. No.

But I guess, you know, it’s a chance to open a discussion with Alice about the attitudes people used to have then. And that was how stories that we were presented with in our childhood were told then. And we wouldn’t tell a story like that now for X, Y, Z reasons.

N&S: Why 1979 specifically?

CC: I think I eventually settled on that date because it was such a time of upheaval in Britain. That’s when Thatcher came to power and my prime minister in the book isn’t Thatcher, but possibly could be, or she’s in that mould anyway. And also because I loved the way it allowed me to dip into my own nostalgia for that time, which was the time of my childhood. So I was nine in 1979 and I was able to revisit wearing brown corduroys and yellow polo necks.

It’s something that I really loved doing in my novel Pet, which is set in 1984. But again, just sort of taking a step slightly further back into my own past with The Book of Guilt was hugely satisfying and also let me create that believable world. If we think about it, New Zealand in 1979 actually had a lot in common with England in 1979. We were watching the same TV shows, albeit perhaps a little bit later. We were wearing the same kinds of clothes. We were eating similar food. We were playing with similar toys.

N&S: We were also taught to revere Mother England.

CC: We were. That was still really deep within our psyche at that time. I remember my UK editor saying to me, did you grow up in the UK? Because this is really familiar to me and this is my childhood and it’s really believable to me. How did I do that? And I said, ‘Well, no, I didn’t. But New Zealand had so much in common with Mother England at that time.’

N&S: I’m watching The Crown. I’m a very late adopter. So much about your book and the home reminds me of it – phrases like, ‘Once was Great Britain’, the stoicism and the pathological adherence to politeness and manners and hierarchy – whether you get to sit on the chintz couch or the damask couch.

CC: I love presenting that kind of mask of politeness and having all those rules in place about who can sit where and the kinds of things that you would serve at an afternoon tea for an important guest. I just loved one of the mothers [in the New Forest home] saying, ‘Fondant Fancy?’ There’s just something really funny to me about that. It is funny, but it also makes me ask, what’s that covering up? What’s actually underneath that veneer?

N&S: The truth lies beneath a Damask covering or behind a vintage porcelain figurine.

CC: We’re distracted by these other things.

N&S: Is it easier to write children characters – their trust and vulnerability is a sort of short-circuit to jeopardy and emotional peril?

CC: I think that’s true. I know in Pet I really wanted the entire story to be narrated by Justine, who’s 12, and in this book, the triplets are 13. There’s something about that time of life that is really interesting to me when you still have a foot firmly in childhood, but you’re also looking towards adulthood as well and you’re starting to figure out that actually adults aren’t infallible. And actually they might not be telling me the full story and perhaps I should be asking more questions than I have up until now.

And so for the triplets in the book, and for Vincent who narrates the book, it is a coming-of-age story. It is exploring that time in his life when he begins to question what he’s always been told and I used the structure of the book to do that. I knew very early on how the book would be structured and that it would be based on these three texts which describe the passage of the boys, but particularly Vincent, from the first section, which is called the Book of Dreams, which is the ledger that their mothers record all the boys’ dreams and nightmares in.

So they exist at that time in the book in this state of dreamy unawareness and their lives are quite idyllic in a lot of ways, but they are fairly ignorant of what is going on beyond the walls of the home. And then the middle section of the book is the Book of Knowledge, which is, of course, yes, the real Book of Knowledge, the set of encyclopaedias from which their mothers take all the boys’ lessons, but it’s also a signal that the boys are beginning to acquire some idea of who they actually are and what the sycamore scheme actually is and what’s been going on at these homes over the years, over the decades. And then the final section is the Book of Guilt, which is the actual book, so the ledger that all their misdeeds are written up in, but also the abiding emotion, I guess, that Vincent has to carry throughout the rest of his life.

N&S: I love him very much. It reminds me a little bit of Demon Copperhead, by Barbara Kingsolver. And the idea that a middle class woman in her 40s or 50s or 60s manages to capture so beautifully the voice of a young boy.

CC: Yeah, I’ve never really sort of stopped to question, well, can I write convincingly as, you know, a 13-year-old boy? And I remember with my very first novel, In a Fishbone Church, writing as a grandfather. And some reviewers commented that it seems really convincing that a young woman in her mid-20s could write like a grandfather.

But I just never really think that I shouldn’t give it a go or that I couldn’t because every character is threaded through with some of my own emotions and my own experiences. And I don’t think at our deepest level that our emotions and the way that we react to, I don’t know, rejection or disappointment or something really joyous happening, I don’t know that that changes particularly much over our lives.

N&S: There’s no death in Enid Blyton. Unlike your books where death, you just know it’s coming. There’s a line, Vincent to Jane, ‘Do you like to read?’ And she replies, ‘As long as someone dies.’ It’s like such a killer line. I burst out laughing. I really like her actually. I really loved Jane.

CC: I loved building Jane. Yeah. She’s wonderful.

N&S: Does someone always have to die?

CC: Yeah, I’m sorry, but I think they do. I mean, this is dystopian fiction, right? I think you have to earn the survival of the ones who make it by paying in blood with other characters. Oh, it’s such a fine line and a fine art.

N&S: You’ve said before that you were superstitious, and it reminded me of a Helen Garner essay on her moving house and how there were boxes and boxes of photos that she just couldn’t bear to throw away because she felt if she threw away the photos, all the people in them would die. I know that you light a candle when you write, but do you have similar fears or things that you must do to fend off fear?

CC: I think about the really rigid schedule and sticking to my word count, and it’s just not a possibility not to hit my required daily word count when I’m in the phase of getting the bones of the novel down. That is the main thing, really, I feel superstitious about – that if I stop or if I take my foot off the accelerator at all, then somehow the entire book will just disappear and I won’t be able to find my way back into it.

And I’ve become more superstitious since I had that period of 13 years of not writing or 13 years between books. And I think that’s really where it comes from, is that fear that, oh, God, that could hit me again. And when I was in that period, I didn’t feel like I had any solution to it or any control over it.

It was just something that I had to accept, ‘well, OK, I can’t write. I don’t know if it’s going to come back. I really hope it does.’

Yeah, and that was so awful that I really crack the whip very hard these days so that I don’t ever fall into a period of not being able to find my way back into a book.

N&S: Even now you doubt yourself?

CC: All the time. And, I don’t know, I thought back when I was starting out that maybe with each successive book that would dissipate a little bit more. But it really doesn’t.

I don’t think that ever goes away. And, you know, with each new book, it feels like, well, now I have to reinvent the wheel again. And I don’t know if this one will work.

And I don’t know if this is the right choice because I have so many ideas for books floating around in my head. And for whatever reason, one of them sings louder than the others. And so that’s the one that I let seize me.

But you never really know. You never really know if that is one that’s going to appeal to your readers. I try not to think too much about that.

I try just to be quite inward looking and to allow my love affair with the book to develop without thinking about inviting anyone else in. Who else is going to?

N&S: And that whole ‘heavy is the head that wears the crown’ stuff. You’ve just been picked up by one of the world’s most important publishers. And that’s extraordinary and wonderful. But with that comes the burden of expectation.

CC: That’s true. And I am feeling that. And there’s no way that I would ever complain. But there are, and especially today with the technology that we have in terms of social media, I do feel that pressure to be making some noise about my upcoming book and making sure that I’m present on social media and posting interviews and reviews as they appear. And all of that is really time consuming, especially since I really still don’t know how to drive Instagram properly.

N&S: It’s a specific skill and a huge amount of energy is required for that.

CC: Yeah, there is. And I’m actually just desperate to sit at my desk and shut the door and get on with the next book. And I haven’t been able to do that for a few months now. And it’s driving me a bit crazy.

N&S: Well, at least you’ve got Tama.

CC: We don’t want Tama touching The Book of Guilt.

N&S: Medicine features a lot – and scarily – in the book. What is the best medicine for you as a writer and in life?

CC: Quiet, just my own company and a lack of pressure to hit… Oh, it’s hard to describe. A lack of expectation from myself to write a perfect sentence first go.

I am a perfectionist and I do rework and rework and rework at sentence level. But I need to be able to take the advice that I give my students, which is to blurt it all out on the page, get it down and then work with that material. And so what I really love … the best medicine for me is solitude, a quiet place and being able to polish and own and perfect the mess that I have blurted out on the page until it’s at a point where I want it to be.

And I find being distracted from that is really difficult.

N&S: If you could live in another era, any point in history, what would that be? Wearing primary colours in the 50s, eating little sandwiches while on a daring adventure?

CC: I think I would be a flapper in the 1920s. I’ve always loved art deco fashion, jewellery.

I don’t have the right hair for the perfect sleek black bob, but in this fantasy, I would. It’s quite easy to answer that one. And especially, I don’t know, with it being the interwar period and with there being that sort of sense of liberation after the end of World War I and not quite knowing what’s actually coming, feeling like you can just get rid of the corset and dance the night away and wear some fabulous clothes while you’re doing it.

N&S: Dreams also are big in your book. Do you dream vividly?

CC: I do. I have always dreamed really vividly and, well, it’s hard to talk about how I use dreams in the book without, again, spoilers. But yeah, I wanted there to be this emphasis on dreams because they can be quite magical territory for people like the triplets or for the boys in the book who are more or less imprisoned in this, in this mysterious home.

You know, their dreams are supposedly the one place where they can escape and they can live all these lives that they can’t in the real world. But at the same time, they can’t really be free there either because every day they have to report what they’ve dreamed and, you know, God forbid they leave something out. You know, that will be really bad news for them if they don’t allow those in authority access to the most private part of their psyches.

N&S: When are you happiest? I mean, you have a beautiful daughter and a partner that you love and your writing, but is there something else, like lying in the grass, when you’re happiest?

N&S: I have such a boring life, Sarah. I really have no hobbies. I have a really busy life. So, you know, I teach full time at the University of Waikato and we have our daughter and I kind of write full time as well.

If you tot up the hours, there’s not much time for anything else. So I’m happiest when I’m able to snatch a little bit of downtime and I can just kind of kick back and kind of do nothing and just spend time with Alan and Alice. So on the weekend, I also love antiques and love being kind of on the trail of a new find.

It feels like a similar rush to the feeling I get when I’m on the trail of something really good in terms of the research I’m doing for a new book. So I love the thrill of the chase in both of those scenarios. Like I said, we’ve just moved house and we needed a little side table for the living room.

So I became obsessed with those sort of brass topped Moroccan, very intricately carved tables with the brass tray on top. And I found one on Trade Me that was in Auckland and it was like, he wanted 150 for it, but was open to offers. And so I offered $120 and he accepted it.

And we went up and got it on Saturday and it was just like, okay, just go on a road trip. He was living in Mamauku, which I’d never been to before, in this amazing villa.

There were these two really cool dogs there and Alice got to play with their daughter while we looked at the table and talked about antiques and stuff. And she got to fire a bow and arrow. And it was just one of those kinds of magical moments that you don’t expect.

And the table itself is really lovely. So that’s what I like doing, that kind of thing. That’s gorgeous.

You can’t really plan, but just as one of those little joyful moments.

N&S: Do you think that people will just sell you something when you make an offer because you’re Catherine Chidgey now? You’re that famous. It’s like, ‘yes, you can have it – I want you to come to my home’.

CC: No, I’m sure that he had no idea that I was a writer. Definitely didn’t know.

N&S: What’s a trait that you like least about yourself?

CC: Perfectionism, which is kind of a double-edged sword. It is the thing that pushes me to make my work as good as I can. But it’s also the thing that makes me feel like I’m not living up to this standard that I’ve set for myself. With every new book, you have this vision in your mind of what it’s going to be.

And it is perfect and shimmering and kind of carved from crystal. And there’s not a thing about it that you would change. And then when you actually sit down at the desk and slog through paragraph after paragraph, and then not quite meeting that standard, it can be crushing.

N&S: A letting-go that needs to happen?

CC: Yeah, I think so. I think the point where you do show it to someone else and get feedback on it is an absolutely necessary moment. And it’s also the point at which you know you’re going to be told some truths about your writing that you probably don’t want to hear.

Like what you want to hear at that point is, ‘it’s amazing’. Or, ‘This is the best book ever written and you don’t need to change a word.’ And of course, you’re never going to get that.

But you have to go through that process. Otherwise, it won’t be the best book that you can write.

N&S: If you think of the film rights to your books being sold, one of the hardest things I’d imagine for an author would be ever to let it go, if you weren’t actively involved in the script or the producing or whatever, of who they’d cast or how they interpreted it. For a writer, that must be like a torture. Have any of your books been signed to film makers?

CC: Not yet. I can see that. With all of them. I mean, Tama’s very particular about who would play him. He doesn’t want any, like, fat, old, kind of dusty, inarticulate bird playing him. No.

N&S: Fair enough. They might make him a crow or a raven. Imagine that, a cross-species betrayal. That would be the ultimate insult, wouldn’t it?

CC: Oh my God.

N&S: Guilt is such an interesting idea, isn’t it? Is there anything in your life that you’ve done or said that has caused you a lingering sense of guilt?

CC: Oh gosh, that’s a really hard question to answer.

N&S: Probably really unfair. I mean, I wouldn’t want anyone to ask me.

CC: I don’t know. The obvious answer for me, and it’s probably one that most mothers can relate to, or most mothers of the 21st century who work full time, is that, you know, there’s not enough of me to give to my daughter. I’m spread so thin. There’s just not enough of me to go around.

And Alan, my husband, was the primary caregiver for Alice from day one, and would often joke to me, you know, when I would get home late from campus, he would say, you know, you’re the Don Draper of the relationship, which was kind of true, but also painful to hear. So yeah, you know, and there’s no solution to that, because I do only have so many hours in the day, and I do prioritise spending time with Alice and reading to Alice and, you know, playing with her and making up stories together and looking at her homework and things like that. But I would like to have more time for that.

N&S: One final question. You are a word. What are you?

CC: I mean, it’s kind of really just riffing off what we were talking about before. But the word that I’m kind of wanting most at the moment is ‘silence’. Just silence. Around me, but also inside my head so I can just devote myself to writing.

The Book of Guilt, Te Herenga Waka University Press. Published 8 May 2025. $38

Catherine Chidgey will appear at the Auckland Writers Festival 13 – 18 May; and the Sydney Writers Festival 19 – 27 May.