The Jukebox Murder

22nd May 2025

A murder that shook Tāmaki Makaurau 70 years ago was adapted into a sell-out play and an award winning novel. Scott Bainbridge recalls the case that still has a hold, in the heart and memory of one who was ‘there’ and which recalls the dark and horrific legacy of the National government’s moral panic and the government’s predilection for hanging young men.

By Scott Bainbridge

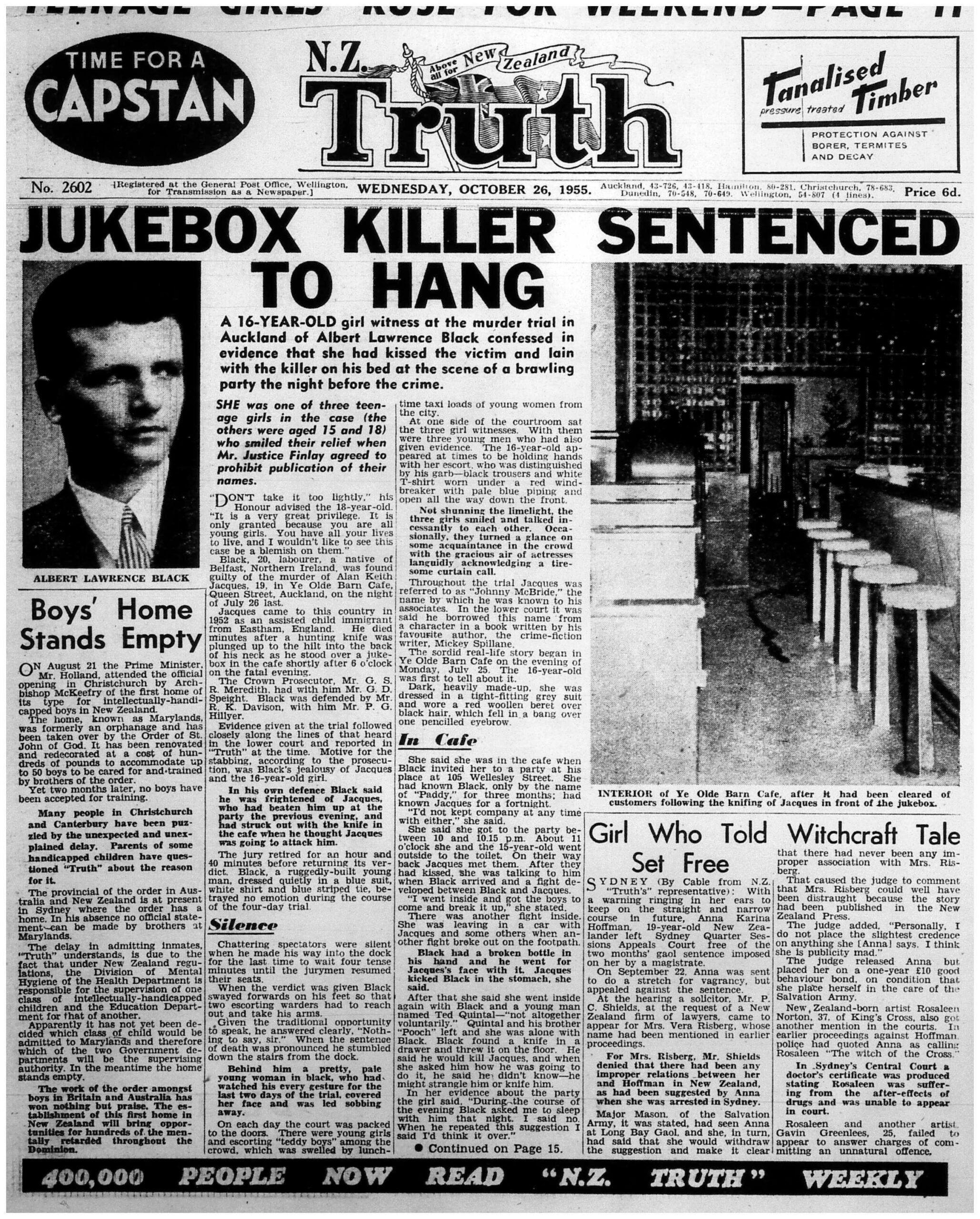

Interior of Ye Olde Barn at the time of the murder.

Seventy years after the infamous Jukebox murder rocked Auckland, it holds the same weight and intrigue as it did in 1955.

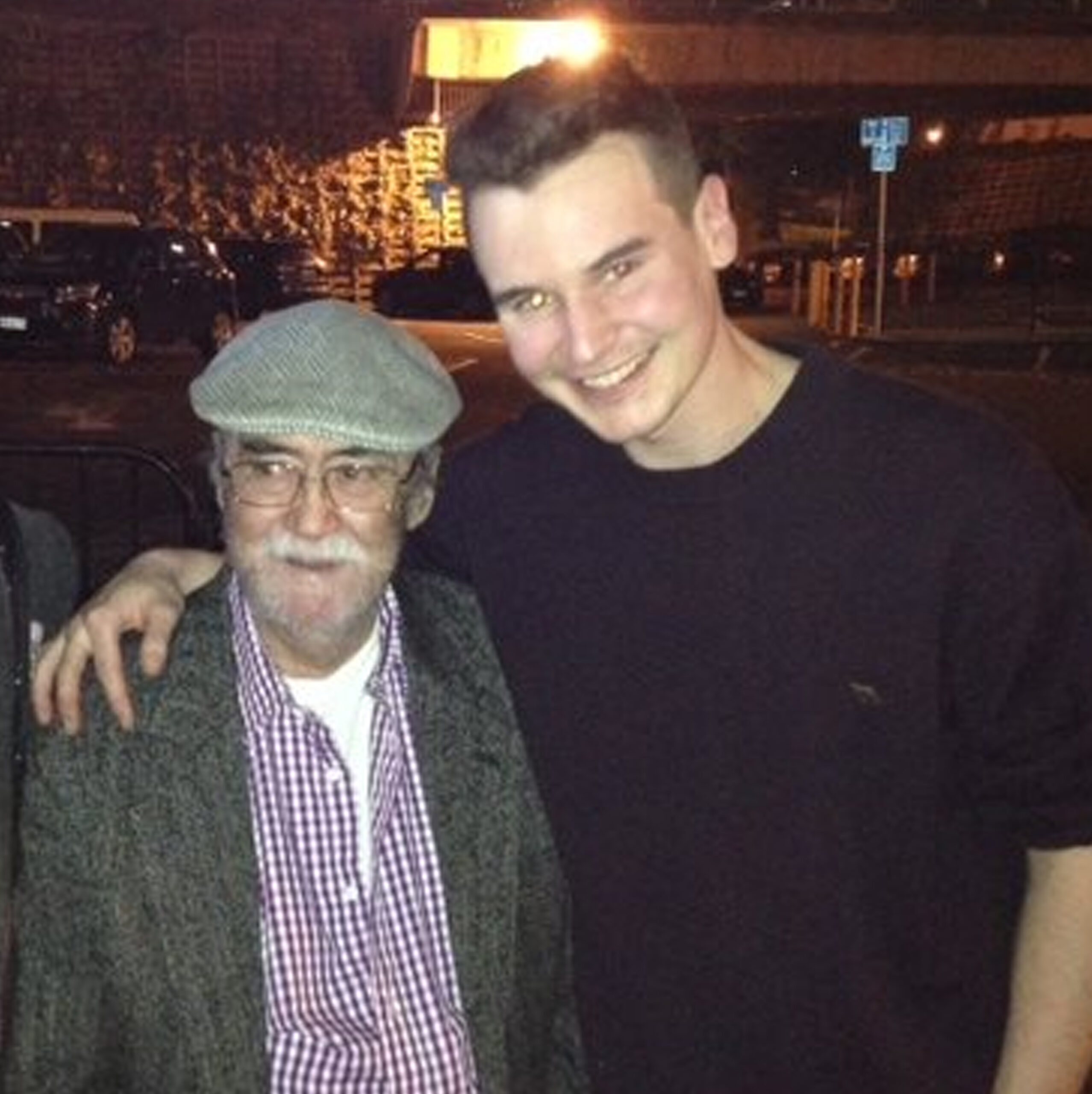

In 2014, playwright Peter Larsen’s adaptation Albert Black played to sold-out audiences. Dame Fiona Kidman’s novel This Mortal Boy is a fictional, but largely respectful, account of the case. It remained a best seller for months and won the Ngaio Marsh Award for Best Crime novel in 2019. I took my friend, Claude ‘Pooch’ Quintal to Albert Black and while he understood some artistic liberties were taken, the play brought back all the emotions for him.

While the audience watched transfixed, I was curious about what Pooch thought. He was friends with both killer and victim. He broke apart the rumble they had at the Wellesley St party and was present the next day at Ye Olde Barn café when Albert ‘Paddy’ Black stabbed Alan Jacques aka Johnny McBride as was selecting a song on the jukebox.

“I watched that boy die,” he told me. “I have watched and read so many accounts of it from people who weren’t there. I hope one day someone tells a truthful account.”

Claude was born in Auckland in 1936. After his beloved mother died, he went off the rails. In 1954, aged 17, he joined the Angels, a bodgie gang. Throughout his life, everyone knew Claude as Pooch. I wondered if it was a gang name. “Nah, when I was a youngster, my aunt thought I looked like a fuckin’ dog so they called me Pooch.”

The roots of the patched gangs can be traced from the emerging youth gangs of the 1950s which comprised bodgies and milk bar cowboys. The Angels were led by Pooch’s close friend, Rainton Hastie, who would become a pioneer of the K-Road strip club scene.

“We called him Ray back then. He was smooth and had the gift of the gab. Everyone gravitated to him; the girls loved him; the boys wanted to be his mate.

“Yes, we were in a gang, but we were harmless. Really, we only wanted to look good for the girls.”

Being at the outpost of the British Empire, young New Zealanders had no access to the modern fashions they saw teenagers wearing in popular American movies. Hastie made friends with American seamen whenever an overseas ship arrived. “We would head down to the wharves and Ray charmed the sailors; paid for their drinks and gave them local currency in exchange for clothes, records, transistor radios, you name it. We bought up whatever they had; long Edwardian coats, colourful shirts, stovepipe pants, winklepicker shoes. Baggy suits we got the local tailors to adapt into zoot suits. We were the flashiest guys in Auckland.”

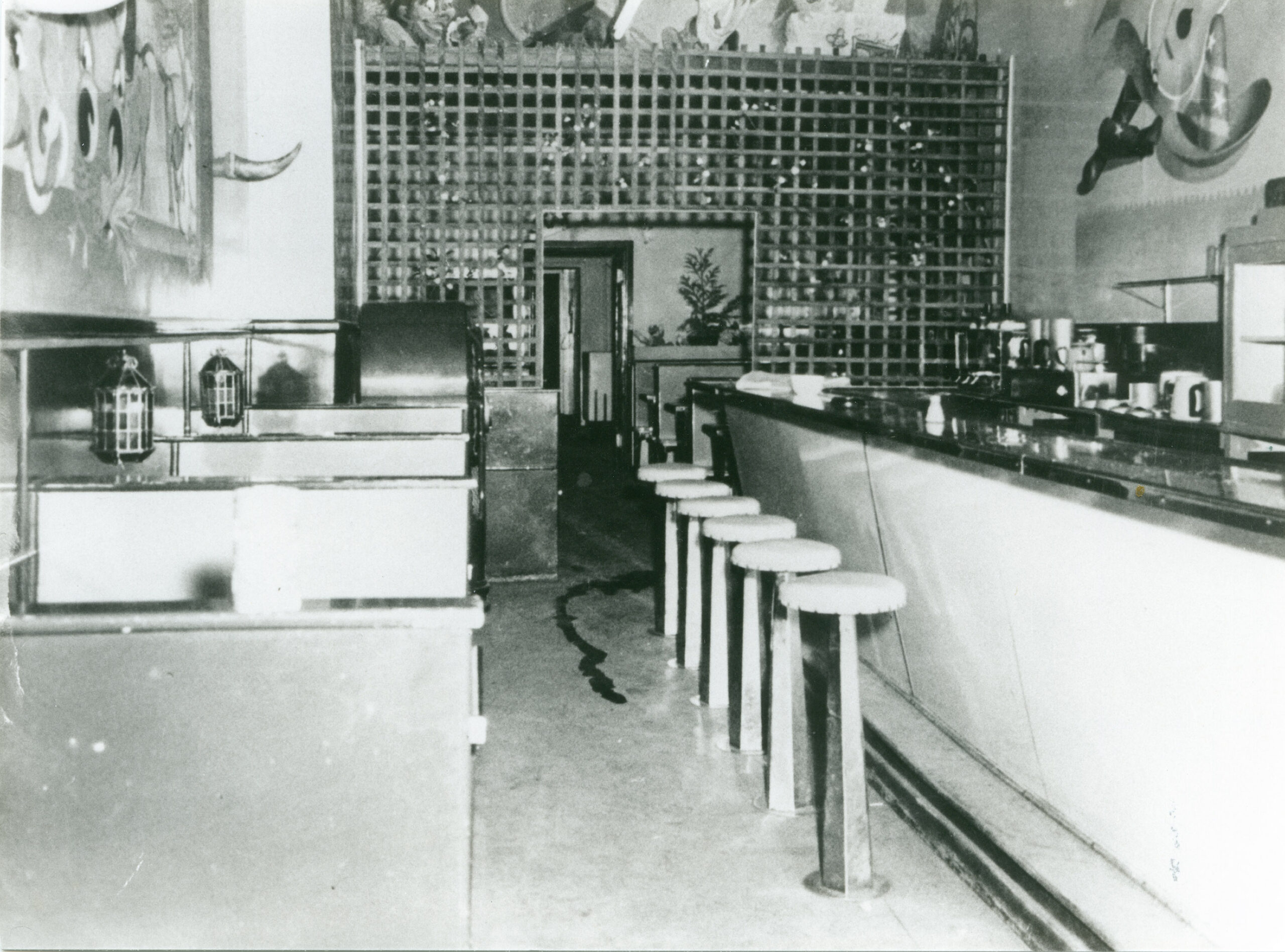

One of the stylish young men Pooch and Hastie befriended was 20-year-old Albert ‘Paddy’ Black, who arrived in Wellington in 1953 as an assisted immigrant from Ireland. He worked his way up the North Island arriving in Auckland. He secured lodgings at a boarding house at 105 Wellesley St, working there as caretaker. A stylishly-dressed Teddy Boy, he quickly befriended the Angels. Being caretaker for the boarding house, Black arranged regular parties at #105 charging an admission price of one pound, or a dozen beer or bottle of gin. Hastie would later credit Black’s sense of organisation as an inspiration for how he ran his clubs.

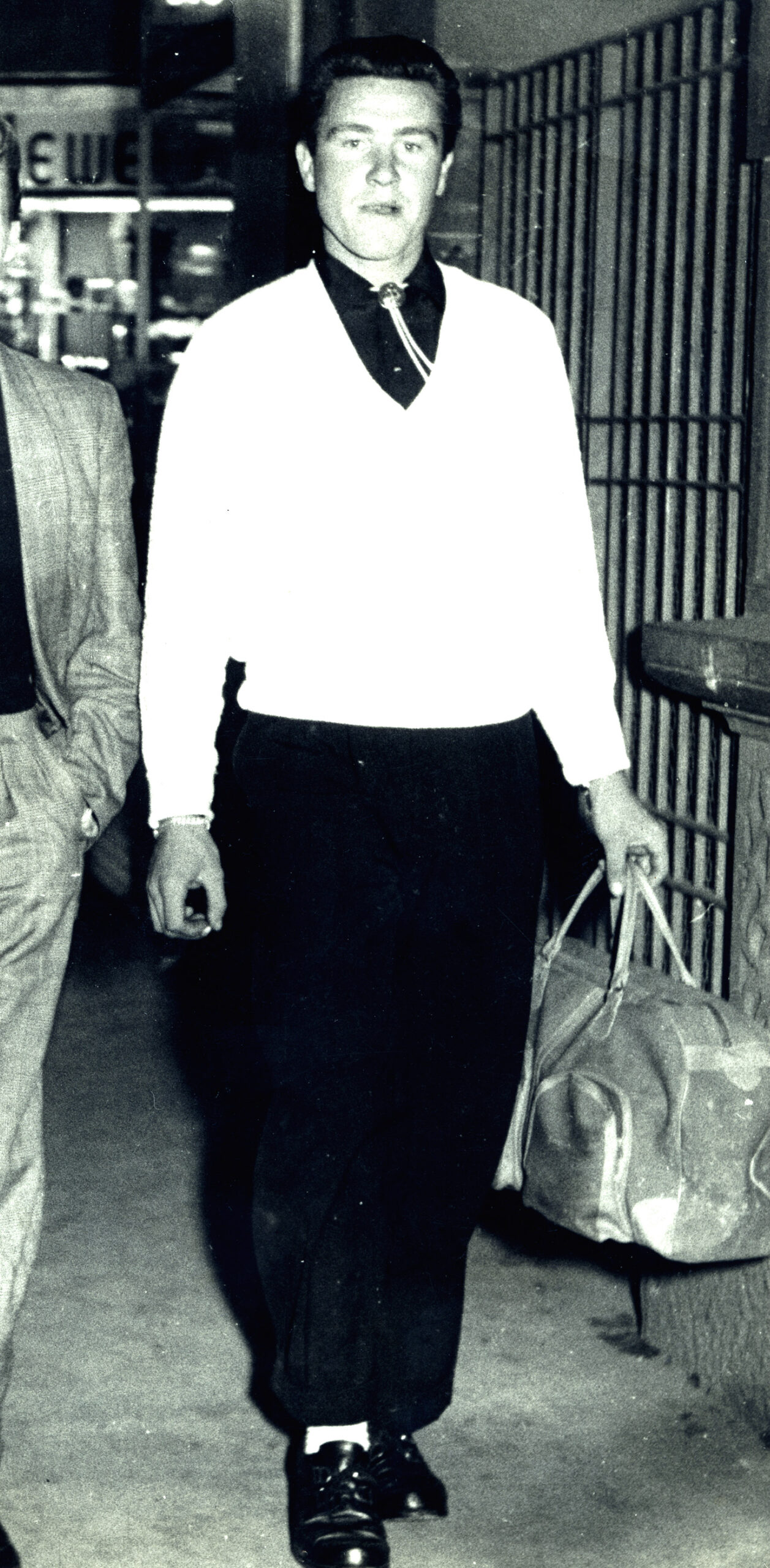

The victim, Alan Jacques who preferred to be known as Johnny McBride, a character in the banned Mickey Spillane book, The Long Wait.

In June 1955, 19-year-old Alan Jacques moved in with Black until he could find his own place. They became friends after previously sharing a room in Wellington. Jacques arrived in New Zealand three years earlier with his sisters as child migrants from England. He worked on a farm in Hawke’s Bay before shifting to Wellington, then to Auckland to work for a passage back to England by ship. Like Black and the Angels, Jacques was a flash dresser and wore jewellery. He went one step further by adopting the name Johnny McBride, the hero of Mickey Spillane’s violent crime novel The Long Wait. Like his fictional hero, he carried a knife and sometimes spoke with an American accent.

In his comprehensive book All Shook Up, about the rise of the New Zealand teenager in the 1950s, Redmer Yska describes the ‘corrupting’ influence of American pulp fiction and juvenile delinquency on our youth. Spillane’s books were banned, as were movies like Marlon Brando’s The Wild One.

New Zealand was intensively conservative and there was a widely held fear the moral fabric of society was beginning to fray with a rise in crime and delinquency.

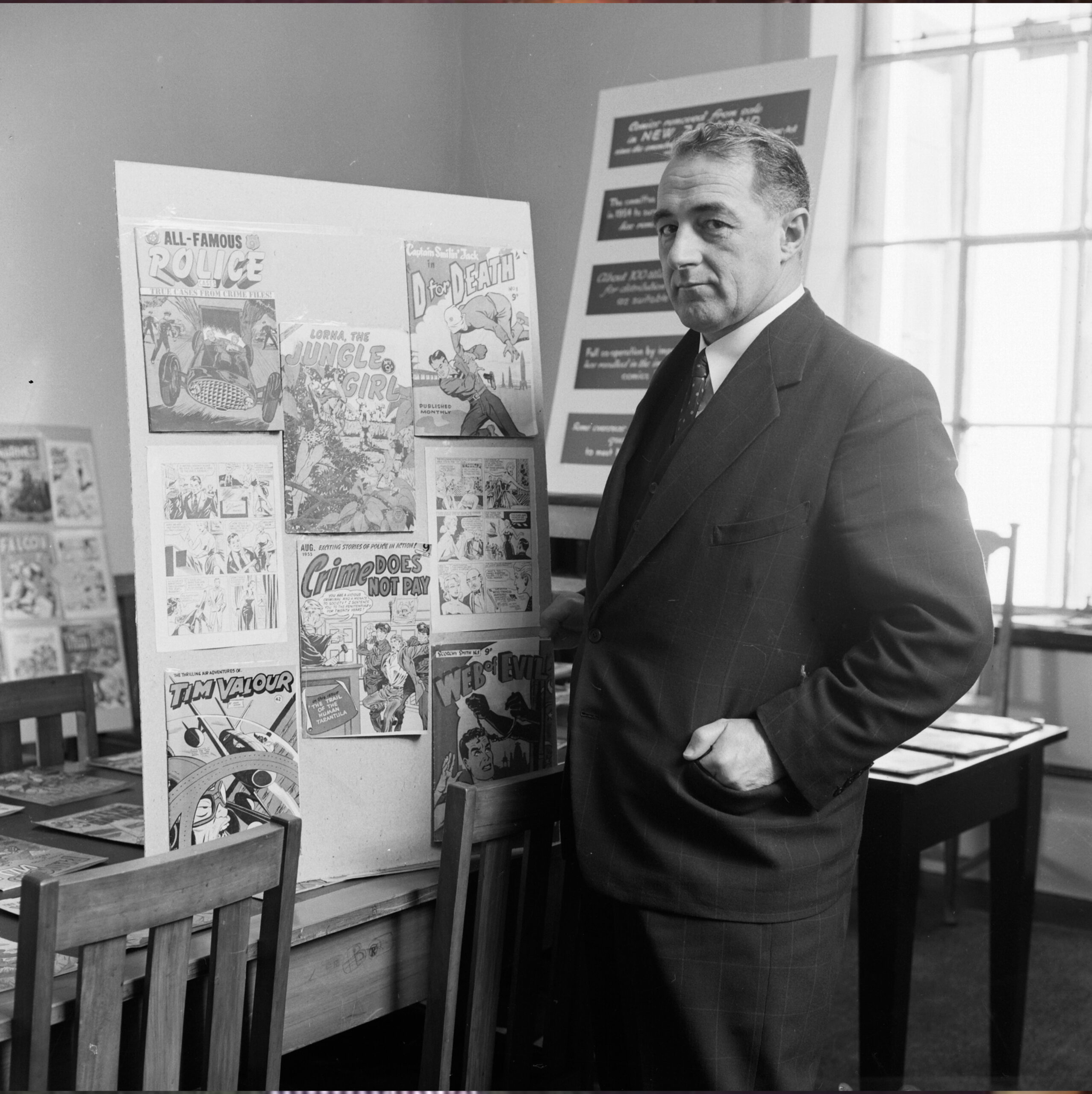

In 1954, sensational news of a sex scandal in Lower Hutt involving teenagers and milk bar cowboys was the catalyst for the National Government cracking down on errant youth and the books, films and new jungle noise – rock ‘n’ roll – influencing them. Many believed the pelvis-thrusting Elvis Presley would be a passing fad. A crusader was found in Karori MP and Attorney-General (later Prime Minister), John Marshall MP, who detested crime and was a fervent supporter of hanging as a capital offence.

Albert Paddy Black, who plunged a knife in the neck of McBride after an argument over a girl.

On the afternoon of Monday July 25, 1955, Paddy Black called into the café Ye Olde Barn at 366 Queen St, hangout for the Angels and other Auckland bodgies. Black suggested a party at #105 that night. Hastie readily agreed and spread the word around. In one of the booths was Maureen and several friends who identified as ‘’widgies,’ the female counterparts to the bodgies. Yska described the girls as preferring short haircuts, wearing low-pump shoes and skin-tight long slacks with wide belts and swagger jackets. There were about 30 bodgies and widgies in their group, but Pooch recalled Maureen stood out from the rest.

“Maureen was 16 and worked as a typist. She came from a well-respected Dally (Dalmatian) family out west. She was a knockout and I don’t know why she hung out with us. I guess she liked the bad boys. We were punching above, but Paddy was smitten and thought he was in with a chance. She snuck out her bedroom window to come to the party.”

“Maureen was 16 and worked as a typist. She came from a well-respected Dally (Dalmatian) family out west. She was a knockout and I don’t know why she hung out with us. I guess she liked the bad boys. We were punching above, but Paddy was smitten and thought he was in with a chance. She snuck out her bedroom window to come to the party.”

Hastie flagged a taxi, bought two dozen beers, and borrowed a steel guitar from the Māori Community Centre. The party was soon in full swing. Later, ‘Squares’ would tell the court that before parties, boys and girls would generally pair off, and it was expected they would stick together for the duration. It was against the rules for another fellow to take a girl already paired. Johnny McBride arrived with his girl, Pat Gribble, and the usual crowd soon turned up. Pooch’s brother, Ted, grabbed the guitar and set up in the corner to play.

Maureen arrived at 10.30pm and went to say hi to Black who was sitting on his bed. Black asked if she would stay the night with him. She politely declined, but he persisted. Feeling uncomfortable and wanting him to stop, she agreed to think about it but had no intention. She ran into Pat Gribble, and both went outside to use the conveniences. When they headed back in, they were joined by McBride. He kissed Pat who went inside and remained outside chatting with Maureen for a few minutes. They shared a kiss, but Black saw them together and flew into a rage, accusing them of having sex, which both strenuously denied. Black did not believe them and advanced towards McBride, who called him a “yellow Irish bastard”. They began to fight but were soon separated when the Quintal brothers raced out to separate them assisted by other guests who had poured out.

Black retreated to his room and was joined by Colin, Pooch, Ted and Hastie, who had just arrived back with more beer and girls. Pooch had never seen his friend so worked up.

The Angels gang at a party, Auckland 1955 (Pooch Quintal on the right, future K-Road Strip Club entrepreneur, Rainton Hastie fourth from right., ‘Squares’, second left).

“Paddy was the loveliest, most generous guy, but had a fiery temper after a few drinks. He had a cut on his cheek and his eye was all puffed up. He asked Ray if he had a knife. Ray lied and said he left it at home. He then got up and tried frisking him. Then he asked Colin for his blade, but he refused to hand it over. Paddy jumped up and lashed out. He threw a chair and bottles at Colin. He had really lost the plot, and it took three of us to restrain him.”

Guests began leaving. Maureen left to catch a taxi with McBride and Pat but when Black saw them leaving together, he ran towards McBride with a broken bottle. McBride saw him coming, steadied and kicked him in the groin. Doubled over in pain with his pride equally injured, Black retreated to his room. Maureen followed and Black asked her again to sleep with him and started kissing her. She pushed him away, but he became rough and throttled her before letting go. When she asked why he wanted to hurt her, he shrugged, saying he was born to kill. He said a doctor had told him he had a year to live but he might as well be dead now. Looking at his facial injuries, he smashed the mirror on the floor and swore to get even with McBride. Maureen went home hoping the grog would wear off and the boys would shake hands tomorrow.

The next afternoon, Pooch and Ted met up at Ye Olde Barn and sat in a booth with ‘Scotty’. In a booth nearby sat McBride, Colin, Lance and Bill Lawson, who had just left the Billiard Saloon. Around 6pm, Black came in brooding and slid into the booth with the Quintals. His face was bruised and he had a black eye.

McBride leaned across his seat and sweet-talked a girl named Marjorie to put the Penguins hit song Earth Angel, on the jukebox. Instead, Marjorie put on Earl Bostic’s Jungle Drums saying she wanted to hear her song first. McBride chatted for a few minutes then rose and walked towards the jukebox. He passed the booth where Black and the Quintals were sitting in but they ignored each other.

“No-one said anything when Johnny walked past. Then Paddy sighed and said ‘I’ve had a gutsful. I’m sick of fuckin getting a hiding all the time.’ Then he rose and walked up behind Johnny who was leaning over the jukebox selecting Earth Angel. Before we could say anything, Paddy raised his right arm and brought it down hard on the back of Johnny’s neck and he slumped forward.

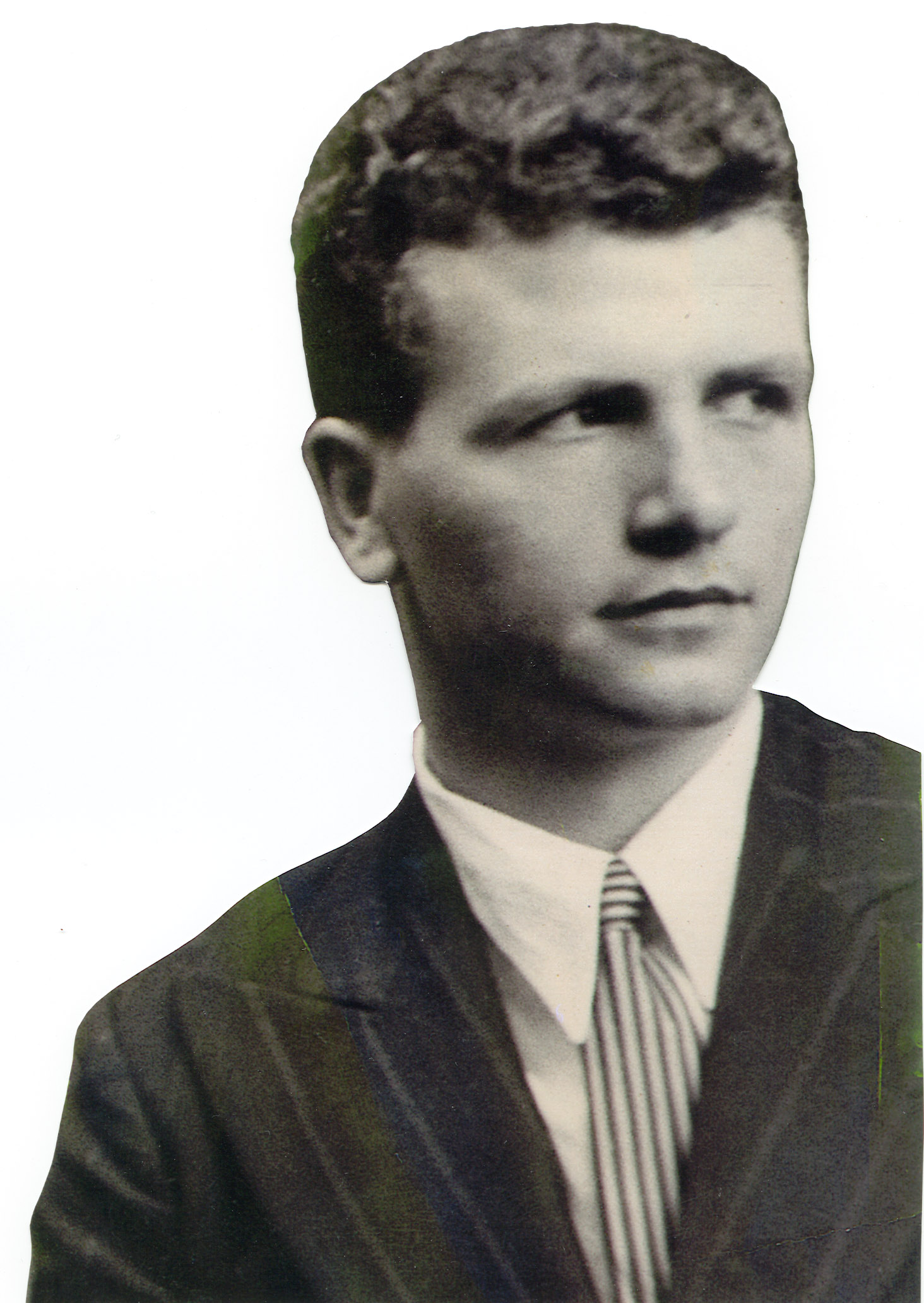

Detective Inspector Leslie Schultz of Auckland CIBs tough consorting squad interviewed Black and prepared the case for court.

“Ted and I raced across thinking Paddy had just given him a rabbit punch and knocked him out. We went to grab Johnny off the jukebox, but he fell back and that’s when I saw the knife go in deep as his head hit the floor. Blood pissed out his eyes, nose and mouth. Paddy just stood there staring and the other guys all crowded around.

“Ted and I vamoosed because we were wanted for car conversion. We went home and I rang Ray and told him not to go down.”

Black went limp and headed outside followed by Bill Lawson. He seemed in a daze and said ‘I have just knifed him. Call the police.’ Lawson assisted Paddy to the police station. Later that night, Black was formally interviewed by Detective Sergeant Leslie Schultz and admitted the attack, pleading self-defence.

“I felt guilty because while I didn’t immediately see the knife, I couldn’t hold on when Johnny fell and, when his head hit the ground, that’s when the knife went in deeper. The injury inflicted wasn’t enough to kill him. It was the fall backwards that lodged the five-inch blade in his neck. I believe that was the point when he died, so I bore some responsibility for years. Maybe he might’ve lived if he hadn’t fallen? I don’t know, but I can’t help feeling today, Paddy would have got off on self-defence or a manslaughter charge at best. He didn’t deserve to be executed.”

Rainton Hastie and the rest of the bodgie and widgies filled the public gallery each day of the trial. In 1993, Hastie told Yska of his last look at Black: “There was probably only one toilet in the courts in those days. Two policemen brought Paddy in to go to the toilet. He was red in the face, though he was sort of embarrassed about the situation. He never spoke, he caught my eye with a sad, pleading look on his face. You know, ‘Can’t you help me some more?’”

Black was the fourth man to be hanged that year. Three of them were barely 20. News of his execution had a profound effect on the Angels and simmering tensions soon reached boiling point. For the first time, the Angels and their rivals, the Vultures, set aside their feud and united in an unprecedented stand against authority (covered in next month’s North and South).

Pooch Quintal and the actor who portrayed him in Peter Larsen’s play Albert Black in 2014.

Future Prime Minister, John Marshall when he was Attorney General in 1955. Marshall was a supporter of capital punishment and crusader against moral chaos. Here he is standing alongside a display of disapproved books and comics that corrupted youth.

After the successful run of Larsen’s play Albert Black, I accompanied Pooch out to Waikumete Cemetery with NZ Herald to find Black’s simple pauper’s grave; a simple white cross saying ‘Albert L Black 5th December 1955’ now barely visible and overgrown with grass. Almost 60 years had passed and not a day went past without Pooch thinking about his two mates and what a waste it all was. He had one wish.

“If I ever win Lotto, I am going to arrange Paddy’s remains to be exhumed and taken back to Northern Ireland. He has a brother still there and he didn’t have anybody here.”

“If I ever win Lotto, I am going to arrange Paddy’s remains to be exhumed and taken back to Northern Ireland. He has a brother still there and he didn’t have anybody here.”

Pooch died two years later, in 2016, without achieving his quest.