Photos: By Ebony Lamb

In Conversation with Michelle Duff

5th June 2025

Michelle Duff is an award winning writer and journalist from Pōneke Wellington. Her book of short stories, Surplus Women was inspired by the young women sent as domestic help from Britain to Aotearoa NZ from the 1850s. Duff talks with Sarah Daniell about entering a beauty pageant at age 9, why she quit her job as national correspondent at Stuff, toxic misogyny in media and politics, and writing Māori characters as a Pākēhā.

By Sarah Daniell

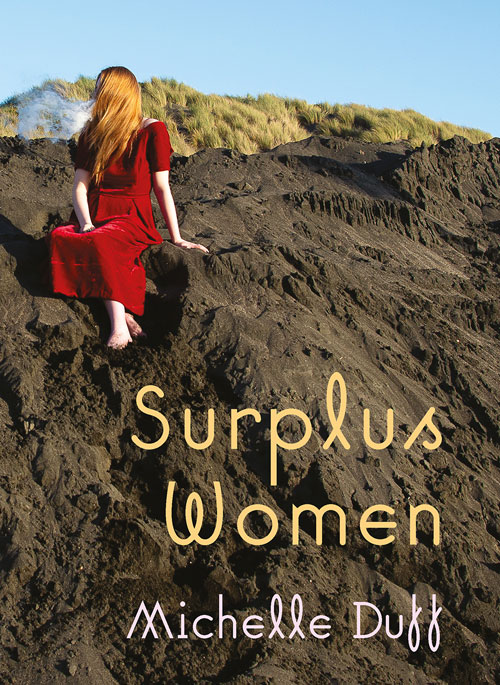

Sarah Daniell: Have you ever seen Andrew Wyeth’s painting Christina’s World? It reminds me of your book cover. This woman, looking away from us. What’s she staring at, what’s it all about?

Michelle Duff: I think that’s the cool thing about it, because you can put yourself in the image, you can put yourself in the gaze, trying to understand what she might be looking at. In Tia Ranginui’s photo, for my book cover, I think there’s something really powerful about the way that she’s so elegant and wearing silk, which is quite precious and beautiful. And then she’s sitting in the black sand dunes. You’re definitely going to get dirty. All kinds of things can happen in sand dunes. It’s precarious. I initially thought it was rocks until you look closer and you realise that it’s something that’s constantly shifting. It’s taken at Castlecliff Beach in Whanganui.

SD: I spent my teenage years at Castlecliff Beach. We’d bike out there. It always felt like there was an edge of menace. It’s a West Coast beach and it’s capricious, but that windswept hot black sand … the mood.

MD: West Coast beaches aren’t like your glamorous Coromandel Beach. They are a bit edgy, gritty. A lot of my teenage years were spent in Himatangi, at Foxton Beach. They’re not the best beaches, but they are fun. There’s something evocative about them. There’s a settler past there, a lot of the first Pākehā settlers came to that beach, and that connected to the Surplus Women story, people coming to New Zealand and finding their place, and their identity.

SD: The young women travelling by ship from Britain to Aotearoa in the 1850s-1870s were described at the time: ‘They’re all attractive in appearance, generally.’ That still reflects how women are supposed to represent, especially on social media. AI posts have weird airbrushed ‘models’ – it’s like the new porn.

MD: God, we’re like, ‘AI is going to take over our life’ and we’re not even going to know what to do about it. We should. With this book, I was really trying to look at it as a lifespan. Because we can’t examine a time, the moment we’re in, without looking into the past. And I think it was really clear that in the 19th century, when ‘surplus women’ were coming over here it was for domestic help, but it was also about having babies, you know, ‘for the Realm’. The way that life is structured here by settlers is a really clear example of the patriarchy, this is the way that our society was going to be structured. That’s not how Māori structured their society at all. But this isn’t that long ago. The shifting sands of time.

SD: How we’ve made gains but then … have we?

MD: I was looking at how things have changed but in fact haven’t changed very much at all. There are characters in the book, like the character who’s a detective. She’s extremely good at her job.

SD: And her husband is an asshole because she hasn’t bought the milk.

MD: She hasn’t bought the milk. She’s an incredibly talented professional woman who’s solving a sex trafficking case and at the same time her husband is constantly ringing her throughout the day, to berate her about why she hasn’t done things for her children, why she hasn’t organised the family home, why she hasn’t brought milk. And she’s feeling guilty that she hasn’t done all the things that she’s supposed to do as a good mother. And this is something many people are familiar with. It’s something that I’ve talked about with my friends. It’s something that you see playing out. There’s roles that people are expected to play, gender roles, and it’s really difficult to get out of those, even when you’re aware of them. The frustration, the anger, the repression, the conversations that aren’t had. I think that’s why so many people have group chats, to be honest.

Tia Ranginui

SD: By the time I got to Roz in the story Toxic, it felt like decades had passed since Jess and Sylvie at the start. As a reader you oscillate from feeling protective, motherly almost, to staunch ally. Do you have a character that stands out for you amongst them, a favourite child?

MD: When I was starting to write short stories … finding the ‘voice’ was like pulling teeth. And then, other times it just sort of flows out. And Colleen Maria Lenihan [Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi author] said, ‘that’s when you find the voice’. Some of it’s quite painful to write, actually. It takes a while and you’re not sure where you’re going. And then sometimes the story arrives almost as if it’s fully formed and you can hear the character talking. And that’s when you’ve found the voice of the character. And so I would say that there were two stories in particular that I have a really strong affinity for. I really love Roz in Toxic.

SD: Why specifically?

MD: Because she represents a place that a lot of us might have been in, which is to be quite badly behaved and self-destructive. And you kind of know it, but it’s also sort of fun. And then there’s a turning point where actually it’s just damaging and you have to face up to that. And I think she’s kind of a badass as well. I enjoyed her and I had a lot of empathy for her.

SD: There’s a kind of gentle forgiveness of someone which I think we all have to do with ourselves – a mix of accountability and forgiveness. And just allowing yourself to be flawed and accept that but aim to grow from that in some way?

MD: I’m so glad that’s what you got from that because, yeah, I think that we can have faith in Roz. The Jacinda [Ardern] book felt really different because it’s not my story. I’m the conduit. It’s not personal – I’m narrating other people’s lives. Also that book was always going to be political – it almost felt completely separate to me. I had my second child, Ahikāroa, two weeks after the book came out. I was writing it when heavily pregnant, working 30 hours a week in a very short time frame. So it all feels like a bit of a fever dream.

SD: Surplus Women is different , why?

MD: I felt really nervous leading up to it coming out. Because even though it’s fiction, I guess like any art, it’s come out of my heart. So there’s an element of real vulnerability and more so than I felt with any of my journalism in that you could look at this work and see me in it. It’s like bleeding onto a page and there’s a roller coaster of being okay with what you’ve written and accepting that when you put it out there you can’t control how people respond.

Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World

SD: You talked about when you were working for the #MeToo campaign at Stuff and covering pretty harrowing stories about sex abuse, that you realised you were mining your trauma as clickbait?

MD: The reason that I eventually left that kind of journalism was because the stories that I was telling were very traumatic. I was writing about things like rape and child abuse and I’d done that over a period, intensively, that last five years that I was a national correspondent. I would say that the amount of support for that work from mainstream newsrooms is majorly lacking, especially for women. A newsroom is traditionally a male dominant space and it’s still run like that. You have to be sort of staunch and I tried when I was at Stuff to get them to acknowledge how difficult these stories were for reporters, and offer the right level of support, but they never did.

I was talking with five or six other journalists who had all left journalism in the previous couple of years, and we went around the table and talked about why we’d left and for everyone, it was one story. One story that tipped the balance. For me, it wasn’t worth it anymore, not for my mental health, not for my emotional health.

SD: What was the story?

MD: Malachi Subecz. The five-year-old who was murdered by his caregiver. I followed that for months. I talked to the family. I remember sitting outside the house where his death had happened. Reading the coroner’s reports. You talk to all these people and you have to read about the worst thing that people could do to other people so that then you can distill it and get people to listen and hopefully make a difference. It takes a toll. When Malachi was killed, he was the same age as my son, so in the end, it actually took a big toll and it’s horrific. I’m still a journalist but I don’t do that kind of thing anymore.

SD: In your newsroom there was, presumably, a higher proportion of women leaders and yet that didn’t make a difference? What sort of support should they have given to you?

MD: People who work in sexual violence prevention or the police, or doctors, all get professional supervision. So they have ongoing visits with psychologists. And we check in on them and make sure that they are, that the trauma or what they’re seeing isn’t impacting on their everyday life. And there’s none of that. You can get three funded sessions with a counselor. They’re not psychologists. They are counselors. One told me it seemed like I had burnout. And I was like, yeah, thanks. She said maybe you could leave your job. I was like, great. Helpful. Maybe turn off your phone? I’m like, yeah, okay. I can’t do that either. None of these are actual coping strategies. But even things like checking in, there’s no actual acknowledgement that potentially this could be harmful to you. And I think that’s just a really old-school attitude. A newsroom is like a patriarchal structure, even if they’re women leaders at the top.

SD: It doesn’t mean that the game has changed, it’s the same model.

And with all the best intentions, the model itself is flawed?

MD: That’s the thing we can’t pretend, that any organisation is exempt from the structural misogyny, structural racism. Any of those influences that are in wider society are within the mainstream media as they are within politics. You can see it. That’s why I admire those wāhine and wāhine Māori in particular, or any woman of colour or any other gender who are doing that mahi and continue to do it because it’s so much harder. Like Mihingarangi Forbes, Annabelle Lee-Mather, Kirsty Johnston and Anusha Bradley. Any journalist, or politician who is still doing this work – I just take my hat off to them because it’s so important.

SD: With feminism, in relation to the pay equity bill, and the era of deranged girl power we’re apparently currently in with the coalition government, it comes back to that thing we were just talking about – you assume that because you’ve got women in power that it’s got to be better? And yet that’s not the case.

MD: First of all, why aren’t we talking about the way women were put in front of that whole issue? They literally got a front pack of women that they could push out and do all of the talking about it so men didn’t have to be involved at all, as if it was just a woman’s issue, so you’re immediately positioning it as something that’s just the ‘girls’ over here who are just gonna have a cat fight about this. Then Andrea Vance wrote her column and they were able to use the fact that she had used the C-word – and actually hadn’t called any of them a c*** – but that became semantics, right? So then the politicians could turn themselves into victims. I think a really good framework to look at this all from is through the lens of white fragility, how Pākehā women were able to try and act as victims in the situation. The main people who were going to be impacted by this are low-income women and also many from women of colour. So the ability to be able to twist that narrative exists because we’re a system that allows it. I mean, come on, they’re adults. Brooke Van Velden and others were subjected to a slightly critical newspaper column. They’re all earning six-figure salaries. They can afford to have nannies. They can afford to outsource their work to other lower-income women if they choose. And now they are front-footing a decision to not pay them fairly. It’s insulting. That’s the antithesis of feminism.

SD: It’s a potent example of how far we have to go.

MD: And it sucks that we get pitted against other women. Why aren’t the men in this conversation? One of my friends had to collar a male journalist to write a story about this, which was also always the case in newsrooms when you’re writing about anything to do with maternity, childcare, sexual violence, unless it’s like a front page or a court story. Ali Mau says in her memoir [No Words For This], we had one man on the #MeToo team and he resigned because he said that it was ‘too political’. Equality is somehow ‘we’ve got an agenda’.

SD: Again, that’s women’s work.

MD: You go over there and just busy yourself with that little activity and we’ll carry on with the business of the newsroom over here. Well, there’s still so much to be angry about, you know, and it’s good to be reminded of that sometimes. We all did get quite angry around 2018, with #MeToo. And then with Trump being re-elected again, and yeah, it started to feel a little bit hopeless.

SD: Like watching The Handmaid’s Tale? We’re already heading towards an authoritarian state, thanks, can you make this stop now?

MD: When I started writing fiction, I deliberately decided not to write a rape scene. I don’t want to read another one of those. I don’t want to see it. Watching really intense graphic violence or, or reading about it – I don’t want to engage with that. Of course I need to engage with the issues, but there are other ways we can do that. And I think, yeah, in a lot of Surplus Women, there are dark moments, but there is a huge amount of hope, I think, in friendship and in love and in seeing the best in people in our relationships.

I try to think, how can I use my skills as a journalist to expose an issue or to ask questions? It’s like a quieter resistance. What can I do in my everyday life, to equip my children to make sure they are asking these questions and feel supported in their culture?

SD: We were talking about feminism and women leaders in the coalition government, and when Nicola Willis delivered the Budget, there was a piece written about her clothing. And the response to that was, how dare you talk about her clothing – that’s really sexist. I was interested in what you thought about that. Should we just never refer to it or did it make an important observation around her disconnectedness with our struggling local economy, a lack of support for local designers?

MD: I think that women should be able to exist in the political arena without having their appearance commented on in a way that takes away from the issue that they’re talking about. And I do think that, in general, we seem to be okay at that. But we seem to be more comfortable doing this with right-wing women. No one really came to the defence of Judith Collins whenever she was criticised, the whole ‘Crusher Collins’ thing, the way that she was characterised as this sort of ball-breaking woman, which was inherently sexist. No one was really up in arms about that. But I thought that Nicola Willis’ aesthetic choices for that day contrasted with the pay equity bill – these low-income women were going to be impacted. It was a very overtly glamorous look. I can’t say whether that was politically ill-advised or not, but the debate around it would suggest that people were responding to that dissonance.

SD: A sort of visual jarring?

MD: I think it spoke to class. You know, I don’t think we speak about class enough in this country in general. We pretend it doesn’t exist, but it does. In the book, I really did try and highlight that. Some of the stories are from people who you would consider working class. There’s a whole story written from the perspective of a child who’s living in transitional housing. I think that we like to pretend most of the time that these people don’t exist when they’re a huge part of the cultural makeup of our country.

SD: We’ve always had this closely-held mythological belief that Aotearoa is a great big, egalitarian embrace.

MD: This is the premise that our country was built on. An ideal that we’re egalitarian. And quite clearly, we’re not. A lot of the reporting that I did was about women and children’s lives; look at the way we treat children in New Zealand. There’s still a huge number of children living in poverty. As we can see with the Royal Commission on State Care, we’ve treated children like shit for generations. And then we tried to cover it up. There’s still that kind of injustice going on. There are kids with not enough to eat and adults who are really struggling. We’re not very good at looking after the most vulnerable. We’re just not.

SD: That’s the role of books, art generally isn’t it? To shine a light on those issues. What books did you read as a kid?

MD: I think I was always interested in reading. I remember one year entering in the Miss Whiritoa pageant. I must have been nine, which is in itself alarming. Why was I being encouraged to enter this beauty pageant? And all these other girls had this really Coromandel look with big blonde hair and bikinis. And I was from rural Taranaki wearing – oh my God, I still remember this – a grey one-piece swimming costume with vertical white stripes. And when it came to my turn and they asked me what my hobby was, I said ‘reading’. The minute it came out of my mouth, I was like, oh that’s not cool. Needless to say, I didn’t place in that contest. But it was fucking horrible, actually.

SD: You love Tim Winton. We talked a bit about Breathe. Which is a coming-of-age story that involves a lot of surfing. Which you do a lot now.

MD: We moved to Lyall Bay three years ago. I love surfing. It’s amazing. It’s like my happy place and the cool thing about it as well is that there’s always something more to learn and just that addictive feeling. I think I’m a bit of a dopamine addict, which I told my husband and he just laughed and laughed as in ‘have you only just discovered this’.

SD: Is there a discovery that you make of yourself, surfing? The struggles that you have or the challenges .. like ‘I’m clearly a bit impatient’ or ‘I’m quite hard on myself’ – what does it teach you when you’re just sitting and waiting?

MD: The thing that I love about it is that first of all, you get to be out in nature. There’s no other way that you’re going to get to be there. You have to paddle out through the waves to be sitting there. There are some days where it’s just so dreamy. I went out the other day and it was sunset and the water was just glassy. There were dolphins maybe 10 meters away from my friend and I, and there’s just beautiful swells you can see coming from the horizon. It’s sensual almost; you can’t think about anything else; you can only be where you are and then you learn to read the waves so you can almost see a swell coming that’s yours, you know from from the horizon and then when you catch it it’s just beautiful like the feeling of being on that wave and turning with it.

SD: There’s a whole conversation around cultural appropriation, writing Māori characters as a Pākehā; do we have the right to? In Surplus Women, there are Māori characters. I know this is very much part of your life, your whānau, but did you ever give pause? Did you ever feel you couldn’t go there?

MD: I thought about it a lot. And when I wrote the book, it was during my MA year in creative writing at the IIML [International Institute of Modern Letters]. We looked at cultural appropriation and whether or not to write characters from other ethnicities or gender identities or whatever. And there wasn’t really ever a consensus on whether or not that was the right thing to do. I wanted there to be Māori characters and characters of other ethnicities in my world, in the world of my book, because it was important to have people represented. I did write a story from the perspective of a Māori boy. And I felt okay. I needed to know what he was thinking. We actually need to know what he’s experiencing too. And I felt that I started writing from that perspective and his voice came out and I felt that I could do that. And it felt like an okay thing to do. I acknowledge that my sons are Māori, my partner is Māori, but that’s not my experience. However, I know what it feels like to be discriminated against on the basis of my gender. It’s not quite the same, but I felt like I could write that. I did try to write from the first-person perspective of a wahine Māori character in another of my stories, and it felt wrong. And I didn’t. It’s not my place to have that voice, that’s not my experience and so I couldn’t.

SD: What have you got on the horizon, apart from waves?

MD: It’s funny because Johnson’s gone away to Paris for two weeks on an art residency and I was like, how am I going to remember what to do with the kids? And he said, ‘write a list’. So I wrote this list so that everyone can see and on the list I’ve written, ‘write 500 words’. Because I’m just trying to write 500 words a day at the moment. That’s just my goal. I shouldn’t even write a list because I know I’m not going to get to the bottom of that fucking list. It’s just going to stay there all week on the Monday list.

SD: Just make every day ‘Monday’ so it doesn’t matter what day you do any of it.

MD: It has ‘organise Ahikāroa’s drawers’, ‘organise my own drawers’. Oof. Like, those things, that’s a day-long activity, both of those, right?

SD: Yeah, that’s actually an all-of-June-July activity.

MD: I know. Why am I so optimistic? So, yes, I’m trying to write a novel currently. I asked another MA what she was doing. She said, I’m trying to write something that might be a long thing and another short thing. I was okay, that’s good. So then I don’t have to commit to it being like a novel. It can just be a long thing.

SD: A long thing that you just see where it goes. It’s a bit like riding a wave in a way, isn’t it? You can’t necessarily control it. You have to get on it, but also go with the flow.

MD: That’s so true. Yeah, because actually, another conversation I had with Tina Makeriti, my MA supervisor, when I asked how long is a short story meant to be? And she said, well, you just have to figure out the length of your breath. I didn’t realise that you could kind of shape what you want. And it’s your breath, but it’s also the breath of the story. Some stories don’t need that many words. The story sort of decides what shape it is as you’re telling it, which is so magical.

SD: Okay, one last question. You are a word. What are you?

MD: Oh, my God. Actually, this is hard. Someone, the Children’s Commissioner, Andrew Becroft, once said to me, after I did all those stories about child abuse, ‘We need people who are fearless and you’re one of those people.’ So I would like to be ‘fearless’. But then, is fearless something good? Shouldn’t you have a bit of fear? I don’t know.

SD: In being fearless, I think you’re implicitly acknowledging that you will have fear, but you’re doing it anyway.

MD: It’s always scary, putting yourself out there. Yeah, every time I paddle out to the surf, you don’t know what’s going to happen. So I think ‘fearless’ is good. I’ll choose that.

Surplus Women published by Te Herenga Waka University Press, $35.