Rina Moore (née Rōpiha), c.1950s. Archives New Zealand

‘You’re taking the place of a man’ – the women medical school grads who changed history

19th June 2025

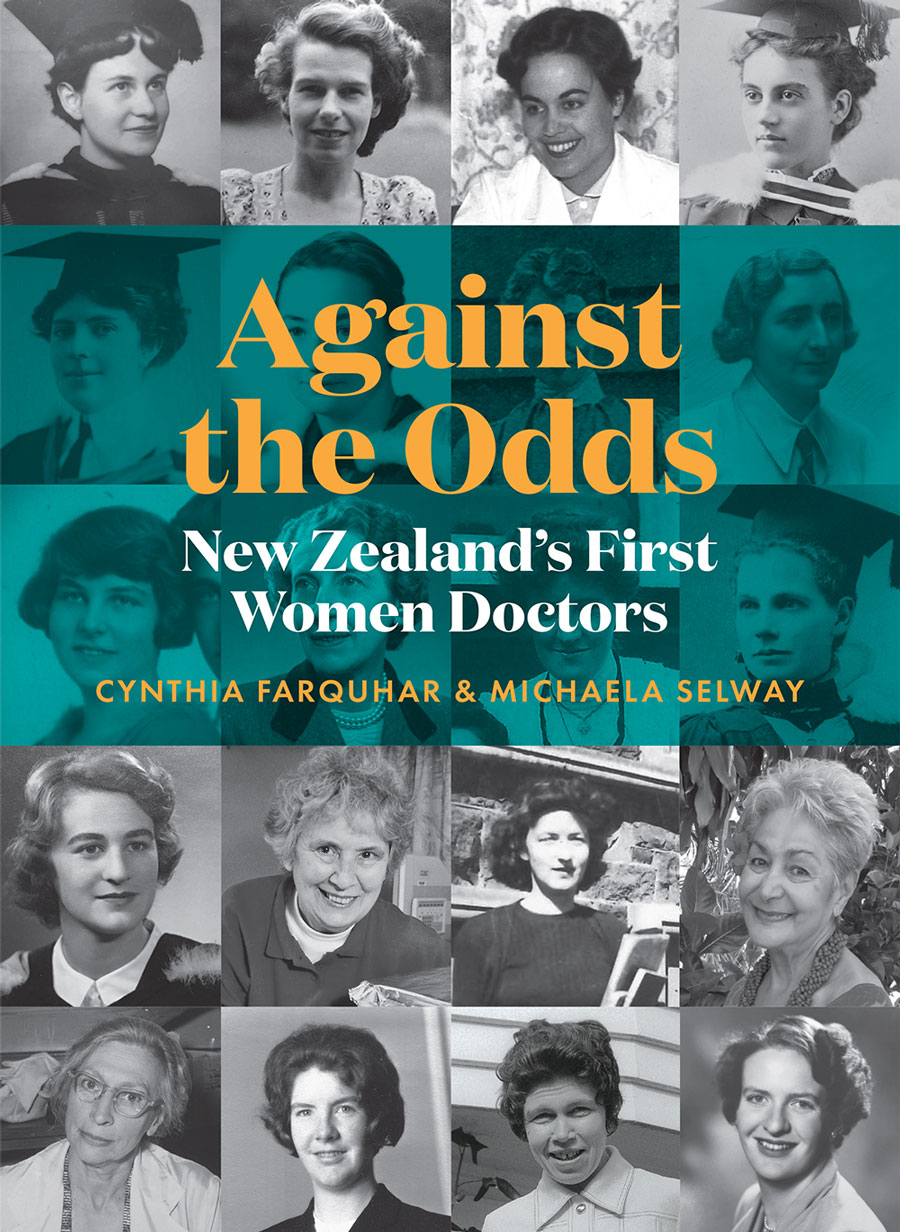

The unimaginably challenging path for women medical students in Aotearoa between 1896 and 1967, is chronicled in the first ever history of the small but determined group who battled prejudice and indifference to succeed and contribute to improved health outcomes. By Cindy Farquhar and Michaela Selway, ‘Against the odds: stories of New Zealand’s first medical women’ includes those who faced even more pressure: the first wahine Māori graduate, Rina Moore, Samoan Papali‘i Viopapa (‘Vio’) Annandale-Atherton, Fijian-Indian Kantha Madhavji Soni, and Chinese graduates Kathleen Pih and Lucy Chan.

Training to become a doctor is never an easy path, even when you are well supported. There is the entry exam to pass, then long hours of study, usually a long way from home, and there are six years of training. As you consider that, then think of being a woman medical student and receiving unwanted feedback about the time you are wasting – as you won’t be able to find work – and that you are taking the place of a man. And finally add to that to be the first woman of Māori heritage to get into medical school.

Rina Moore (née Rōpiha) was the first Māori woman graduate in 1948

In 1948, Bishop Frederick Bennett, the first Māori bishop of Aotearoa New Zealand, was excited by her graduation.

“New Zealand’s first Māori woman doctor will take her degree next month . . . an illustration of the ability of members of the Māori race to succeed in any pursuit”. Bishop Bennett said “Mrs Moore studied hard to within a few days of having a child and went back to her studies as soon as possible afterwards, leaving her husband to look after the baby on the Plunket system.”

Rina descended from Tipi Tainui Rōpiha (Ngāti Kahungunu, Rangitāne), who was the first Māori secretary of the Department of Maori Affairs, and her mother, Rhoda Winifred Te Tūruki Walker (Te Whānau-ā-Apanui), had worked as a nurse among Māori in rural areas before their marriage. She had no problem passing the entrance exam and at the start of her second year, she married Ian Leslie Moore, a law student from Nelson. The couple’s first child, Karin, was born in August 1945. Rina’s mother stayed in Dunedin for six months to help. She and Ian had three more children. In 1949, Moore began working as an assistant medical officer at Ngāwhatu Psychiatric Hospital in Nelson, primarily with female patients.

Moore was intelligent, bold and articulate — qualities that meant she was sought after as a public speaker. In the late 1950s, she was invited to participate in a series of hui with young Māori leaders discussing issues such as urban migration, high crime rates, mental health and education. She realised, like many Māori migrants to the cities, that she had missed out on much of her Māori heritage. Despite many attempts, however, she never mastered te reo Māori. In 1960, she was one of five speakers to the first South Island Conference of Young Māori Leaders in Christchurch, where she spoke on the topic, ‘Health trends in modern Māori society.’ Later that year, she was made an inaugural member of the Māori Health Committee formed by the Board of Health, one of only two Māori doctors.

Moore strongly advocated for education about sex and relationships in schools, and she was one of the first doctors in New Zealand to prescribe the contraceptive pill in the early 1960s. In 1961 she prepared a paper on family planning to present to the influential Māori Women’s Welfare League (MWWL). Moore was also actively involved in promoting higher standards of education for young Māori. In 1962, as the Māori representative on the Nelson district committee, she helped organise a national campaign to raise funds for the Māori Education Foundation.

In 1963, after 15 years at Ngāwhatu, Moore resigned. During these years, men had been promoted over her, her health was poor, and her career prospects were restricted by the lack of a postgraduate degree, which would have required training overseas. Instead, she set up a private psychiatric and counselling clinic in the family home.

In 1966, Moore was diagnosed with cancer of the breast and lymph nodes. She had the tumour removed, followed by radiotherapy treatment. From that time onwards, she was fearful of dying in pain and suffered periods of depression. In 1975, she had a mild stroke, and shortly after, it became apparent that her cancer had returned, this time in her brain. She died in November 1975 at the age of 52. One can only imagine how much more she might have achieved had she worked for another decade or two.

The only other Māori medical woman graduate up to 1967 was Judith Karaitiana who graduated in 1956. She married and did not work following this.

But Rina Moore and Judith Karaitiana were not the only women who stood out. Papali‘i Viopapa (‘Vio’) Annandale-Atherton (née Annandale) was the first Pacific woman medical graduate in 1964 and first Sāmoan woman doctor. Viopapa (‘Vio’) was born at the Moto`otua at the National Hospital in Apia, Sāmoa in 1940. Her paternal great-grandfather was Thomas Annandale (1838–1907), a well-known Scottish surgeon, and her maternal grandfather Ta`isi Olaf Frederick Nelson was a leader in Sāmoa’s independence movement. In 1935, the Labour government established a schooling system in Sāmoa that aligned with the New Zealand syllabus including scholarships, and Viopapa received one and was able to attend Epsom Girls Grammar in Auckland. Following this she won a university scholarship, arriving at Otago University in 1959 as a 19-year-old, not knowing anyone. She initially felt a bit lost, but the other young women at St Margaret’s College were friendly. Another student from her year recalls that she was referred to as ‘hot chocolate’ by one of the medical staff. She graduated in 1964 and spent her first year as a house surgeon in the surgical and medical wards at the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh, where her grandfather had worked and where his portrait hung on the wall.

In Edinburgh, she met John Atherton, who had also just graduated and was doing his internship. They married in 1965. The family spent several years travelling back and forth between Britain and Sāmoa. From 1971 to 1974, they lived in Sāmoa, where they both worked at the Moto`otua National Hospital in Apia. When they returned to Britain, Annandale-Atherton worked in family planning in Sutton, South London, as well as studying at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, where she obtained a Diploma in Tropical Public Health in 1976.

Viopapa Annandale-Atherton in 2019 (Left)

Courtesy James Atherton and University of Otago (Right)

In 1982, the family returned to Apia, where she worked with the Ministry of Health. For a time, she was acting director of health. In 1979, she became a member of the Pan Pacific and South-East Asia Women’s Association. In 1993, they set up the Soifua Manuia General Practice Matautu in Apia, where they both worked until 2007. Annandale-Atherton retired from her clinical work at this time.

In 2019, Viopapa Annandale-Atherton was awarded an honorary doctorate at the 150th anniversary celebrations of Otago University. ‘Breaking barriers and creating opportunities for women and girls has been the driving force of her life’. As a result of her services to Sāmoa, she was awarded the chiefly title Papali’i from the village of Sapapali`i in Savai`i, which was conferred by the head of state, Malietoa Tanumafili II.

Kathleen Pih was the first of only two Chinese doctors to graduate before 1967. She graduated in 1921. Kathleen was born in China and came to New Zealand with a missionary who she called Auntie Maggie, and had adopted her (informally) when she was a young child. She experienced a lot of racism as at that time the Chinese had very limited rights.

“In those days it was really hard to be a Chinese person in Otago. It was quite demeaning … Of course, I knew I was Chinese. I wished I wasn’t. It was all right when I was on the farm. But then in 1915 my aunt wanted to send me to the best girls’ high school in Otago. I was the only Chinese.

“In the girls’ school, the girls were just not too friendly. In the university too, the medical girls were really arrogant. There were so few girls, and they came from good families, from the moneyed class, and they really looked down on the Chinese. They were not nice to me at all.”

Following graduation, she worked in New Zealand, then returned to China as a missionary doctor. She married another doctor, and spent most of her career working in Asia eventually returning to New Zealand to retire in Tauranga.

Kathleen Pih-Chang, 1929. Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena

The only other Chinese woman to graduate before 1967 was Lucy Chan (married name Chung) who came to New Zealand (aged 7) during the Second World War as part of an immigration plan for the families with husbands working in New Zealand. She entered medical school in 1957 and graduated in 1964, one of only a handful of women and the only Chinese woman. She worked in Whakatāne, one year in Hong Kong and then returned to work at Waikato Hospital. Lucy started as a General Practitioner in Hamilton in 1974. “They needed a female doctor. I think I was the first female Chinese family doctor in those days. I did obstetrics and built up my own general practice.”

Lucy had a very successful career as a family doctor in Hamilton, was well loved and trusted by her patients.

“I had no regrets being a family doctor. I felt my training allowed me to serve and help other people with their lives … even after I retired, I’d meet patients coming up to me in the supermarket proudly telling their children that I was the doctor that delivered them. Often the ones I delivered had children of their own. That is because I have spent all my life in one place — in Hamilton.”

The single negative experience that really irked Lucy was her status as an ‘alien’ in New Zealand. “I had to report to the police station every time I left to go down to Dunedin for the Medical School and also when I returned to Hamilton. Every year I had to do that twice. I had to do that even up to the mid and late 1950s.”

Like many of her cohort of refugee children, Lucy’s determination and unyielding spirit made her an outstanding citizen of her country of adoption.

Kantha Madhavji Soni was born in Nadi and grew up in Lautoka, Fiji. Her parents were of Indian heritage. As one of the fortunate ones, Kantha attended Natabua Secondary School a few miles out of Lautoka in an isolated farming area. Her school had accepted girls for only the four years prior, and although she was one of about 10 girls in her class of thirty-five, previous years had only two or three girls.

As a naïve 16-year-old, she moved to New Zealand without her family, living first in the YWCA and enduring a period of loneliness, before moving in with an Indian family who she boarded with for the next four years. She found that the Indian community in Auckland was very small, and almost everyone came from India rather than Fiji.

Kantha began her medical school studies in 1955. She was one of 12 female students in her medical school class, and for a long time she was the only Indian woman in Dunedin, other than the wife of a house surgeon, with only a handful of male Indian students around the university campus. Kantha lived in St Margaret’s hostel for three years where she recalls adapting to the diet was quite difficult. Kantha went home to Fiji every second year throughout her secondary school and university years.

After graduation she had many roles in medicine across the country. Mostly as a general practitioner but also established community health care clinics in Grey Lynn. In 2011, Kantha was awarded a New Zealand Order of Merit for services to the community and to medicine.

Against the Odds: New Zealand’s First Women Doctors, by Cynthia Farquhar and Michaela Selway. Massey University Press, $55.