BOOKS

‘As the shock sank in, life had to keep moving on’

The start of his second year at the University of Otago was not an auspicious one for a young Grant Robertson. His mother had called with shocking news that his father had been arrested for theft from the law firm where he worked. In chapter three of his memoir, Anything Could Happen, the former Labour Finance Minister describes a family unravelling that would lead to divorce and his mother coming out.

4th September 2025

Eventually we headed up home to Brockville. It was a surreal scene. Dad was in the laundry taking clothes out of the washing machine to transfer to the dryer. It could have been any day at all. I rushed into the room and gave him a hug. He shook with his sobbing but could not say anything. He did not really say much from that moment on, shutting down on what he had actually done.

In the days that followed we faced a dilemma. It was not clear exactly what the next steps would be. We made the decision not to widely share the news until we knew more. But Dunedin is a small town.

My flatmate Andrew had inherited some money and had, on my suggestion, invested it with Dad’s law firm. A few days after Mum had broken the news of Dad’s arrest to us, he received a letter from the firm, telling him that his money was safe but that they had dismissed Dad after an investigation revealed theft from the business. Andrew left the letter on my bed. I went for a walk with him and told him all that I knew. He, like each and every friend, was amazingly supportive.

When it all added up, Dad pleaded guilty to stealing $120,000 over a period of 10 years. He was adamant that he did not think he was responsible for all of that. But he had no proof, and the law firm said there was no other explanation for the missing money. And what did it matter really? The breach of trust was the same whatever the amount.

As the shock sank in, life had to keep moving on. Stephen had a scholarship to go to Rutgers University in the USA to do his PhD. He and Delwyn left shortly before Dad’s sentencing. The scholarship was not enough to live on, and Dad had told them he would be their financial backstop. The next few years, short on money and with only letters and expensive toll calls to keep in touch from so far away, would be very tough for them.

Come late September it was time for sentencing. We were realistic that a prison term was likely. Perhaps six months, we were told, or maybe some kind of community sentence if he was lucky. In the historic surroundings of the Dunedin District Court, Judge Ron Young made clear his distaste for what Dad had done. But when he handed down the sentence it was still a shock — two years in prison.

In that moment I wondered if my father would survive that long. Dunedin Prison (right next door to the court) was a Victorian era relic. Cold, sterile, lacking in almost any outdoor space, it was home to a wide variety of prisoners from murderers to minor drug users. White-collar criminals like Dad were regarded by the other inmates as second only to paedophiles in the order of disgust.

The first phone call we had with Dad the morning after sentencing he sounded almost excited. He was clearly delirious and trying to reassure us that he would be okay. My first visit with Mum (Craig had an exam that day) a few days later laid bare the reality. Going into the prison through a series of vault doors set into cold brick, huge sets of keys jangling in the wardens’ hands to open them, each corridor getting ever darker, was frightening. The visiting room was a strange airless hallway. Dad looked terrible and sounded worse. He had already been roughed up and had begun eating his meals standing up with his back to the wall to avoid giving anyone a chance to surprise him. He tried to put a brave face on, but this was going to be a long lag.

Grant & Jacinda at Jacinda_s farewell function after her valedictory speech April 2023

Over the next year and a half, much of my life revolved around visiting Dad. I tried to go every week, sometimes twice a week. It was falling more and more to me to see Dad through his sentence. At the end of 1991, Craig left Dunedin to go to journalism school in Christchurch. Mum was increasingly and understandably starting to distance herself from Dad. Their marriage had been in name only for several years, and his betrayal of her was the final straw. She discussed the timing of divorce with me — but agreed it should wait a little. In his very frequent letters to me and during my visits, Dad would talk about his counselling and some of the things that had led to his offending. But mostly he would talk about Mum, and how he wanted to be a better husband when he got out. It was heartbreaking — but also frustrating. It felt like he was minimising what he had done and simply spending his time plotting his return. My visits sometimes ended in me walking out. But I always went back.

On Saturdays and Sundays I worked in the fruit and veggie department at the New World supermarket in South Dunedin, as I had done since school days. I had inherited one of the family’s second-hand cars. My route to work took me past the prison. Dad knew the timing of the trip and would look out the window for me. As he saw the car approach, he would reach his hand through the bars on his second-level window and wave. I would toot the horn — and start to cry.

As time wore on, Dad began to feel more at home in prison. His knowledge of computers saw him employed in the office, rearranging the systems and schedules. He worked in the kitchen, which in turn led to him enrolling in a cooking course at the polytechnic where he would occasionally be able to step out the back of the room and say hi if you, ah, happened to be there.

He also began working with other prisoners. I had been at school with some of them. Dad’s pastoral care had him writing letters to girlfriends, filling in forms, drafting parole applications. The more he told me, the more it became clear that prisons were not providing much, if anything, to help rehabilitate the inmates. A lot has changed in the intervening 30-odd years — and a lot has not.

Bill English once said that prisons are a moral and fiscal failure, and he is right. On the fiscal side it costs over $100,000 a year to house a prisoner. But with a recidivism rate of over 35%, and over 50% for those who have already had a conviction, much of that money is wasted. The money could be far better spent keeping people out of prison — investing in education, training and programmes for substance abuse and anger management.

The morality question is more complex. Crimes have been committed, and a punishment is expected. But the critical issue for me is that too many politicians (and the public) think people should be sent to prison for punishment rather than as a punishment. The loss of freedom and liberty is the punishment. With the exception of a very small number, everyone in prison is going to re-enter society at some point. It would, then, make sense for the whole time spent in prison to be an exercise in rehabilitation. Sadly, that is not the case. In New Zealand rehabilitation mostly means providing some form of alcohol and drug addiction counselling and mental health support. In my time in government we increased resources for these programmes, but more needs to be done. The Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Courts are a good start. Community sentencing that focuses on the source of the addiction is vital.

Dad did get some counselling, and strong support from the prison visiting programme run through one of the local churches. His counselling drew out a range of issues that he shared with me. Most shocking was the story of sexual abuse in his early teens at the hands of a grocer he worked for in Timaru. He also highlighted some difficulty in his relationship with his mother. It was clear Dad had huge trust and self-esteem issues. Of course, none of this justifies his offending, but his stories started to give me an insight into what had shaped his character.

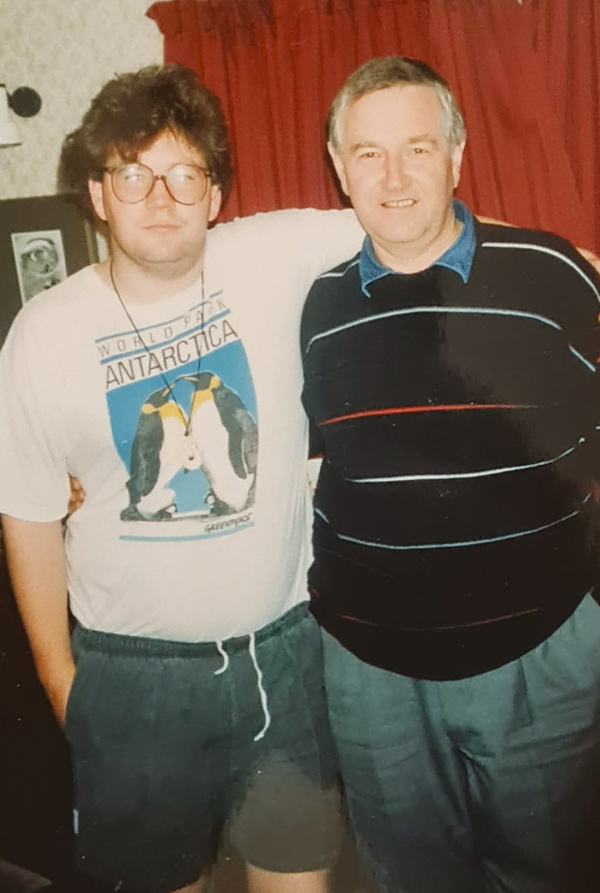

Grant with his-father, Doug, early 1990s

The other major insight was into the impact of imprisonment on perpetrators’ families. Dad’s conviction was front-page news in Dunedin. Some of Mum’s friendships withered away as people, either judgemental or frightened, backed off. The same applied for Dad. Ian Simpson, the Rector of King’s High where Dad had chaired the Board of Trustees, was a frequent visitor, as were some others from the church. In recent years I have been a strong supporter of the charity Pillars, which provides support to the children of prisoners. The isolation and stigma that children and families face is immense, and little thought is given to it by authorities. Pillars is remarkable in what it has achieved and would be a valid candidate for some government support.

For my family, and especially for Mum, it was also hard going financially. She scraped by for several years before getting the role as archivist for the Presbyterian Church, a job she loved and stayed in until her retirement. Her extraordinary resilience during this time still blows my mind. She did as she always had told us to do: she worked hard, and kept looking out for others, especially her children.

Dad’s imprisonment meant I was now most definitely eligible for student allowances, but proving this presented a challenge. When I visited the student support staff at Otago they could not believe that my father’s income was zero dollars. I was reduced to photocopying the front-page story from the ODT to take in as proof.

Dad’s spell in prison would finish at the end of 1992. He was released on parole six months ahead of his sentenced time. He had in many ways been a model prisoner — so much so that the prison had issues working out what to do without him, and asked him to come back and work a few hours a week to keep the systems running. He also volunteered with PARS (the Prisoners Aid and Rehabilitation Service).

This apparent successful transition from prison was not, however, the full story. Mum went through with her divorce plans, leaving Dad devastated. Reintegration was tough from a financial and emotional perspective. He stayed in a series of small and cold flats, and found it difficult to get work. Moreover, he struggled to find a network of people to accept him. The church was his comfort zone and provided him the solace he needed.

Extracted from Anything Could Happen: A memoir by Grant Robertson. Published by Allen & Unwin Aotearoa New Zealand. $39.99.