ARCHIVE HIGHLIGHT

The Haunting of Detective Inspector Ron Cooper

In February 1988, Robyn Langwell’s North & South cover profile on Detective Inspector Ron Cooper, detailed the case that would haunt him, and the nation: that of missing Napier school girl Teresa Cormack. It was a case that would alter his life and career.

25th September 2025

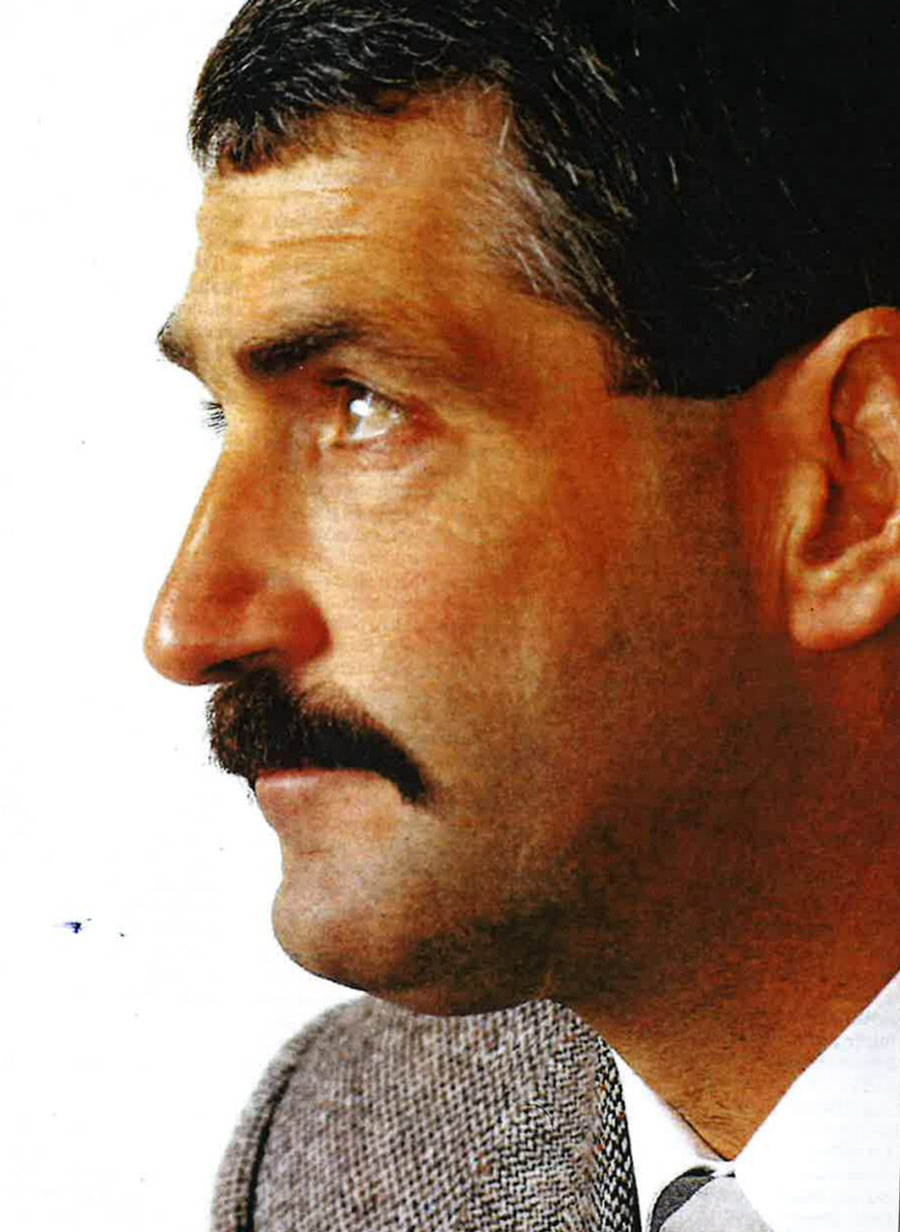

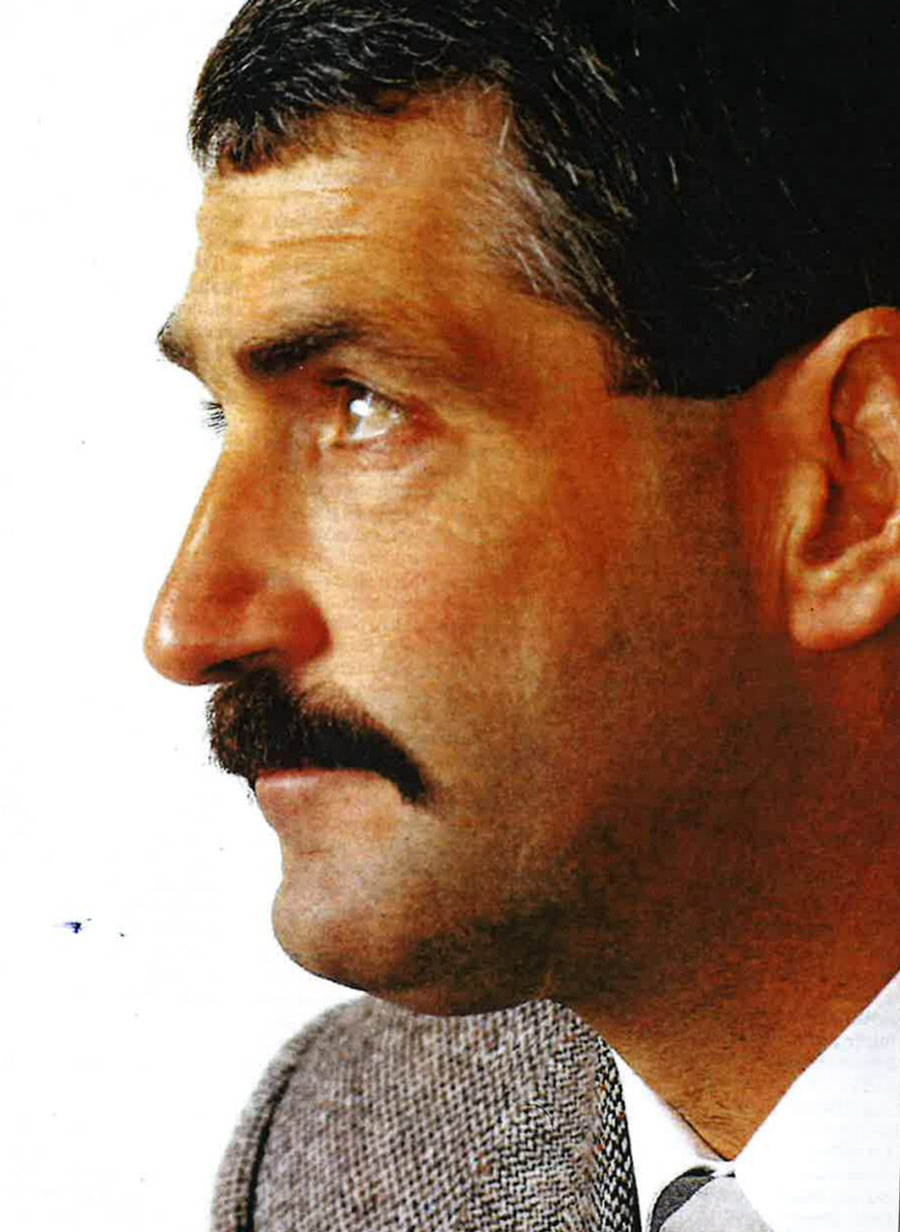

Ron Cooper. Photo: Barry Durrant

The call came at 7.30 on Saturday evening. Ron Cooper had just hopped out of the spa pool and was heading for the fridge to get another beer. He was feeling pretty pleased with life. The All Blacks had just cleaned up in the World Cup rugby final, the neat, white, Lower Hutt weatherboard house was full of kids and noise, and “Coop” was among work friends. He had to tell them all to shut up when the phone rang. He could hardly hear a word his boss, Detective Chief Inspector Ted Lines, was saying.

Lines explained quickly that he knew it was a hell of a time to call, and he knew too that it wasn’t Cooper’s turn to go, but there was no one else available. There was a small girl missing in Napier. She’d been gone since Friday morning and it didn’t look good. It was starting to look like an abduction, possibly murder.

“They always ask if you’re prepared to go,” says Cooper. “You can say no, and in this particular case I would have had more reason than most. We try and share the out-of-town jobs around and I’d already done two in the last year. We have an on-call system and I wasn’t even on call that weekend. One of the detective inspectors was involved with a big table tennis do and he asked me to cover for him.

But I’d never say no. My initial reaction was one of enthusiasm, you get a tingle in your guts. It’s a sense of excitement – not in a callous way. But murder’s the big one. It’s the apex of our training – the number one offence.”

Cooper grabbed a sports bag, collected a few changes of clothing, his running shoes and toothbrush, and by 9.30pm, with two other Wellington detectives, was on the road to Napier.

He wouldn’t be home to stay for five months. And his life and police career wouldn’t be quite the same ever again.

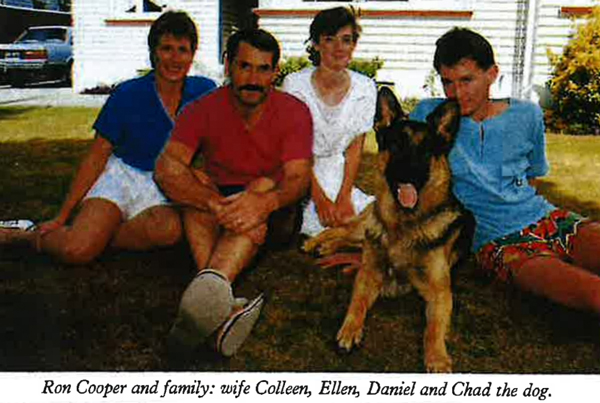

Ron Cooper and family: wife Colleen, Ellen, Daniel and Chad the dog.

AS THEY sped north, Cooper was already going over the options for his investigation and the ironies that found him driving around the country in the middle of a cold winter night.

What had happened in Napier that weekend was a police district commander’s nightmare. At 8am Friday June 19, the body of 16-year-old Colleen Burrows had been found on the banks of the Tutaekuri River at Brookfields. Napier Detective Inspector Barry Hunter – coincidentally a close friend and longtime marathon running adversary of Ron Cooper’s – automatically stepped in as officer in charge. His case was to be a clear-cut investigation, with notes like signposts which led Hunter and his men to two Mongrel Mob members.

Within two days of the murder, the detectives had confessions about a planned night of sex that went wrong and led to the woman being kicked down and stamped on by capped boots, punched, beaten and finally run over by a car.

A murder trial in late November took a week and jury deliberation of five hours to finally put that inquiry to rest. Ron Cooper was to have no such easy run.

Because Barry Hunter and most of his CIB staff were committed to the Burrows inquiry, when a young mother reported that her six-year-old daughter hadn’t returned from school (and inquiries had shown that she hadn’t in fact reached school in the morning), Chief Inspector Bruce Scott (the police district commander for Hastings and Napier) began to get a bad feeling about his weekend.

After 12 hours of searching by as many police as could be mustered and 600 volunteers from the local community – with no results – Scott rang Wellington and cried for help.

He requested a detective inspector to head an inquiry and as many staff as could be spared to help out in Napier.

There are only four detective inspectors in the Wellington division – and Ron Cooper was the third one called.

TERESA MAIDA Cormack turned six on June 18. She was a breathtakingly beautiful child. With dark eyes, cherubic face and long, shiny hair falling in tendrils about her face, she stood out on any street.

She lived with her 22-year-old mother Kelly, two-year-old sister Sara and her grandfather in a state house in the drab, working class suburb of Maraenui, five minutes south of the centre of Napier. She was a happy, confident, outgoing child, despite the fact that there had already been considerable turmoil and heartache in her life.

Her parents’ relationship had been strained for some time, there’d been fights and anger over her father’s inability to get and keep a job, and in June, he was living in Auckland with his own parents.

Kelly promised that things would get better and soon when he got a job and some money, they’d all be back together again – one big happy family.

On her sixth birthday Teresa waited especially late into the evening. Her father had promised that he would drive down from Auckland for her birthday. But at around 9pm she was finally, reluctantly bundled up to bed. Her room was bright with presents, but the one she had hoped for didn’t arrive.

Ross Cormack will doubtless punish himself forever for the decision he made that day. After calling in to see his brother in Hamilton and having four drinks, he decided to spend the Thursday night in Hamilton, and to see Teresa sometime later.

She awakened the next morning, Friday June 19, fractious. She didn’t want to go to school, but Kelly placated her, dressed her in a bright red raincoat and promised that her dad would be there by the weekend. She kissed her beautiful daughter, told her not to worry, and said goodbye – forever.

Leaving home at 14 McLaren Crescent at 8.30am Teresa set off for Richmond School less than a mile away. She didn’t take the most direct route to school, preferring instead to walk a slightly longer way to pick up her friend Maria Taukamo, on the corner of Cottrill Crescent and Venables Avenue.

There are always a number of “if onlys” in most murder cases, and the first two in the Teresa Cormack case happened early on. First, if Teresa had only been walking her route to school half an hour later, she would have come under the passing eye of most of the city’s police force rushing to where Colleen Burrows body had just been found. “If only that body had just been found half an hour later,” Ron Cooper laments, “we might have deterred the offender because of a large and obvious police presence in the area.”

The second if only happened when Maria Taukamo’s parents decided to take their daughter to school by car and omitted to include Teresa in their plan. When Teresa arrived at the corner where her friend was normally waiting, she found no one, and began the walk to school alone.

Teresa made it safely to school, but told a school friend she met just inside the school gates between 8.40 and 8.45, that she was going home. She was seen a short time later, by someone who knows her, running across Bledisloe Street to an empty section, and there was another positive sighting of her standing outside the section (Bizarrely, the old house formerly on the section was the site of a Napier double homicide just four years earlier).

Next, a child in a red raincoat was seen walking along Riverbend Road and a Maraenui man in a car reported that he nearly ran over a little girl who darted out onto the crossing outside No. 172 causing him to stall his car. The small girl was with an older (13-17 year-old) European girl, not wearing a uniform and they seemed to be arguing. The man also reported seeing parked on the other side of the road a blue Morris 1000 or Minor with a man standing behind the vehicle on the roadway close to the crossing. He got the impression the girl in the red raincoat was running across to the man.

The last definite sighting has Teresa almost back at her home – within 500 metres of safety. A nine-year-old late for school came across Teresa swinging on bars at the end of a walkway just half a minute around the corner from home. The time was between 9.05 and 9.10 and Teresa told the girl she was going to see her Dad.

There is one more sighting – possibly a red herring, maybe not. A woman reports a small girl walking along Wycliffe Street, near the intersection with Riverbend Road being approached by a stooped European man dressed in a long, fawn-coloured raincoat. The woman isn’t sure if it’s Teresa, but the child is wearing a red raincoat.

The sighting is a bother, particularly when it is tied to a report of a man exactly a week earlier seen in the company of a very young girl in the area.

Extensive inquiries follow as to who the child might be if it’s not Teresa. Despite the fact that such a child would have been noticeably late for school (and school logs all late arrivals these days) police can’t find any other child it could have been.

The man goes down in police files as “Long Coat” and to this day remains a frustrating and “tantalising possibility” to Ron Cooper.

RON COOPER was born in Christchurch, the oldest son of four children of Roy and Noeline Cooper. His father was a beat policeman on the streets of Christchurch before moving his family to the small West Coast town of Ross (population 500) when Ron was 13.

It was the “best possible place” to grow up and its hunting, shooting, fishing rusticity shaped Cooper’s life to this day.

He was raised a good Catholic boy and attended St Mary’s College – “it doesn’t exist anymore” – in Hokitika. Roy Cooper was the country constable – the sheriff. From an early age, he taught his son about shooting, took him rabbit hunting then deer stalking and bought him his first gun at 16. One of the best memories of growing up was going to dances until three or four in the morning and then sneaking home in the grey dawn light to go hunting.

He vowed he’d never be a policeman, but somehow he didn’t stick to it. “I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, I thought about a career as an army officer. I was leafing through a careers book at school and cracked a joke that I could try out as a nurse because I could get five stockings – and on the next page there was an ad to join the police force. Don’t ask me how it happened, but before you knew it the papers were signed and I was on my way to Trentham. My father was, of course, very pleased.”

Trentham police training college was a bit of a culture shock. “You had to be in bed at a certain time with lights out, and they checked. Then you had to be up at a certain time with beds made. It was a regime of spit, polish, clean, scrape and shine for 18 months, and then suddenly you’re out on your own, earning five times more money than you’ve ever seen before, there’s no one to tuck you in at night and you can actually go out and arrest someone. It’s a fairly major step, not frightening, but it takes a bit of getting used to. In those days there wasn’t the violence there is now, so there wasn’t that element of fear.”

At 21, two years into his career, in October 1970, Ron met and married 18-year old Colleen, a freight company typist from Epuni in Lower Hutt. She remembers him as being “all shining bright and new” in his blue serge. He jokes about childhood lovers, but there is a stern pride about the couple’s 17 years of marriage. He was the type of man who wanted his wife at home and within a year, their son Daniel was born.

The young Constable Cooper did three years in the uniform section of Wellington Central before turning his attention to CIB work. “It seemed to me that was the only place to aim for if you wanted to get into the meaty police work like murders and the upper levels of crime.” He was accepted, after an initial six months trial, into two years of intensive training rotating through the rape, fraud, car, vice and drugs squads, mostly in Lower Hutt.

He graduated as a detective on March 28, 1974 – the day his daughter Ellen was born – finishing ninth out of 27 in his intake, a placing he believes should have been sixth had he not suffered pre-paternal stress in the final week of exams.

Wet behind the ears, Ron Cooper with his young family, was posted to Taumarunui as the town’s sole detective. It was supposed to be a quiet town with any crime being pretty low level stuff. But new boys are sent to be tried, and in the first week a young girl was waylaid on the way to school and nastily indecently assaulted. “Fortunately I identified the offender – a visitor from Waitara – within a week. It was a good ice breaker, I’d been sent to replace Jock Black, a detective who’d been there for years and who was thought of as irreplaceable. After the arrest, the little girl’s father came to me and said they’d been a bit worried when Jock left, but that I was obviously going to do okay.”

Next came a homicide in Raetihi that really rocked him: “A Waikune prison escapee broke into an old couple’s house and tried to steal their car. He shot at them in bed, hitting the old man who managed to stagger to the phone before the guy beat him to death with a rifle. He knocked the old woman senseless and she wasn’t found for 24 hours. When I got there, there was a Santa Claus suit hanging on the back of the bedroom door. The old guy had played Santa Claus that week, and there were letters to Santa on the kitchen table. They were covered in blood.”

In 1976, Cooper was transferred to Auckland against his wishes. He was promoted to uniform sergeant, but the boy from the Coast was miserable in the city. “For the first six months it was terrible, we found Auckland so very unfriendly, so spread out. I guess it was just the big city thing, a place where the job rather than people always came first.”

But after getting a police house in New Lynn, making a few friends and discovering the calming effects of running in the cool green of the Waitakeres, Ron began to enjoy the big smoke almost too much.

“In Auckland I discovered I needed challenges. Ambition unfolds as you go along. Promotion draws you to seek further promotion”

Working for the drug squad on one investigation that stretched on for six months of up to 16 hour days he realised he was doing the job at the expense of his family. “I was flat out and everything has its cost. I was putting Ellen to bed one night and she asked if I was ever going to start being home regularly like real fathers.”

The investigation by and large failed to achieve its ends and after months of covert operations and using electronic surveillance, Cooper and his fellow officers failed to get even one conviction.

A later 12-month inquiry was much more successful cracking an international hash importing syndicate and gaining a seven year sentence for Austrian Peter Schnellinger.

In 1982, Cooper had had enough and asked for a transfer on promotion back to Wellington. Returning as a senior sergeant in the uniform branch he did three months in the watchhouse before returning to CIB. His promotion to detective inspector came through in March 1986.

At the time of Detective Chief Inspector Ted Lines’ call to the Cormack case, he was Wellington Patrol manager working out of a ramshackle but friendly office in Waring Taylor Street in Central Wellington.

”It was a bitter day on June 27th, when a local woman walking her dog, saw what Napier had dreaded finding all week.

COOPER ARRIVES in Napier at 2am on Sunday. He’s tired and eager, but sleep is important right now. Tomorrow he must be sharp. His accommodation at the Victoria Hotel, a muddy brown building on the front is far from the most salubrious in town – but that’s the police force for you. He falls into a narrow single bed at 3am thinking about organisation and getting things right.

“The early days of a homicide inquiry are a controlled frenzy. You have to be so careful about your time, be in control, because there are so many people who want to call on your energies,” says Cooper.

Because there’s already one homicide inquiry going on in the two storey Napier station, Ron is allocated space in a large building across the road, left empty by the Forestry corporatisation.

Ron arrives at 8am and is briefed by Inspector John Bethwaite who’s been in charge of the inquiry to date. There isn’t much to tell. All available police have searched streets, waterways, empty houses and vacant sections in the Maraenui area. On Saturday they are assisted by 600 local residents. For some this must have a feeling of deja vu. Four years earlier they were involved in similar fruitless searching for still missing Kirsa Jensen.

The Cormack case is set up from day one as a homicide investigation: “We hoped that she might have been picked up by some loopy lady. But it had all the hallmarks of a homicide,” says Cooper. “We had nothing – no bag or clothing – that would indicate a snatch.”

While searching goes on throughout the Sunday, Cooper discusses strategies with his 2-i-c, Detective Senior Sergeant Alan Aitken, the 35-year-old head of Hastings CIB.

Aitken – “AJ” to all – is a colorful foil to Cooper’s somewhat serious front. He has a penchant for wearing matching socks and knitted ties in shades of mauve, turquoise, and fire engine red.

On Monday, still without a hint of a break, Cooper and Aitken take to the street – “to sniff the air”.

Maraenui is a southern dormitory suburb bordering on farming and horticultural land. To say it is a trouble spot would be to exaggerate but it’s fair to say that most of the Napier police’s ‘clientele’ live in the area. It’s a large state housing development which has been labelled Napier’s Otara or Mangere, but that’s unkind. Here at least there are gum trees and some attempts at gardening around the rottweilers chained to old rusting V8 cars.

On their familiarisation walk, Cooper and Aitken decide that it’s logical to presume that if the child had been abducted she’d be taken south into the country. Another small girl had gone missing from Maraenui a year before, and had been driven south, but on that occasion a suspicious member of the public had called the police. As it turns out, such reasonable assumptions are 100 percent wrong.

By Tuesday, still with nothing to show, Cooper goes to make himself known to bewildered 22-year old mother Kelly. “It’s not something I have to do, but it’s a personal thing, we’re working for her. She was an amazingly together young lady. She impressed me. She didn’t cry and she didn’t believe that Teresa was dead, she wouldn’t let herself believe it. But she asked if we did. I told her to take her cue from us, that we hadn’t abandoned hope, despite media speculations.”

By Friday Cooper had joined the speculators and made a press release that he believed Teresa was now dead. “And bingo next morning her body was found. Talk about an unholy coincidence.”

“They rang me at the hotel at 8 to say a body had been found at Whirinaki Beach. I didn’t have a clue where it was – it turned out to be the opposite compass point to where we had been looking.

“It was a great sense of relief – for us, because it gave us something to work with. Before we had no scene, no body, no clues, nothing. And a relief for the family too. They could begin to grieve, instead of living on their nerves and false hope.”

WHIRINAKI BEACH has two moods. It can be an evil-feeling place – steely grey, wind ripped and violent – and it can be gentle, with ice-green wavelets tinkling on fine stone shores – a place where local fishermen come in search of a giant mullet.

It was a bitter day on June 27 when a local woman ‘walking her dog, saw ·what all Napier had dreaded finding all week, the body of a small child clearly visible under the heaving branches of a koromiko tree just above the high water mark.

From 20 metres away the woman knew the significance of what she could see. Sobbing, she turned and ran to the first house in the Whirinaki beachside settlement 400 metres away.

Four young detectives were sent speeding to the beach. They went just close enough to the body to confirm the woman’s fears, and then began cordoning off the area. The scene is the policeman’s treasure trove. If you want to put it crudely, it must be treated delicately. Here lies all the evidence he needs to get a conviction, and all he may ever get to help him solve the cringe. Minions aren’t allowed to touch, and on that bleak morning, the eager young policemen stood around in the 4C cold blowing on their hands, wiping the sea mist off their faces, waiting for Ron cooper to drive the 16kms, so he could be the first to turn his wily eye to the scene. They also had to deal with the irate local fishermen who weren’t prepared to listen to any reasons why they couldn’t go surf casting.

“Driving out there of course I was excited. We’d been chasing our tails for a week, trying to make sense out of little kids, looking for men in long coats, looking for Morrie Minors, swimming round in a bloody great ocean, with no sight of land. But if you’ve got a body you’ve got something to work on. I thought come on my boy, now’s our chance to get you…

“We expected she would have been raped… it’s not my first child murder… it’s never just another case… she was a poor little defenceless girl…. Of course you’d like to kill someone… but it’s all business, it’s got to be routine… you’ve got to put everything out of your head, all emotion, you’ve got to think about doing it right… you’ve got to work for her and her family… you’ve got to get the man who did this… it won’t bring her back, but you’ve got to get him – for her…”

“I always remember my first murdered body. That moment never leaves you. It was back in Upper Hutt in 70 or 71. I was doing CIB training. This guy had come home and found his wife in bed with another man and shot them both and then himself.

“The woman had been shot asleep, she never woke up, but her visitor had leapt up and been shot through the back. He still had a look of surprise on his face. Then the husband sat down in the corner, put the gun under his chin and blew half his head and face off. It was too hideous to take in – almost. But the crazy thing is, that the thing I remember, absolutely stark in my mind, is the fact that the guy had taken his shoes off and left them neatly placed beside the front door. And the other thing was that the place was so average. There were supper things still out on the table in the lounge. This was ordinary, everyday, ho hum life and then suddenly death had visited. It was a powerful feeling.

“You have to look past the blood. I remember a detective sergeant early on telling me not to do anything for 10 minutes. Just stand there and look, take time to have a really good look, absorb, before you move, then make your decisions.

“It’s always been very good advice”

TODAY, a cairn of stones, a driftwood cross laced together with seaweed and a sprinkling of spiral seashells mark the place where the child lay. It was an ideal spot for an offender. Whirinaki Beach streams out for a mile in either direction. You can see the length of the beach from where she lay, but you can’t be seen. There’s a child’s swing in a Macrocarpa tree nearby and wild flowers and blackberry finger their way up the clay bank to the road only five metres away.

Now that there was a body, there followed a number of set police moves, executed as in a chess game.

“Nobody had touched her when I got there. I went with Dr Pedlow, the local pathologist and we looked at the body in situ. He gave me an opinion on the length of time it had been there. Initially he thought that was not very long, but later after the post mortem he was able to say that the situation was consistent with her being abducted on the 19th and being killed and placed there shortly afterwards.”

The beach is probably the worst murder “scene”; it’s so sparse. Normally, you’ve got blood, furniture, you can build up a picture of people’s movements by the scene you find, but the Pacific Ocean had operated like a great floor cleaner. That week there’d been sweeping tides, washing the beach clean twice a day. “It was a toughie, it certainly wasn’t a gift,” says Cooper laconically.

At this point the precise policeman becomes non-committal about exactly what it was he found at the beach: “There are some things in any case that only the police and the offender know. We like to try and keep it that way.”

Although Cooper won’t say how exactly the body was found, it seems likely that Teresa was left clothed, exactly where she’d been murdered. She wasn’t buried, although very high tides on the day before she was found, may have uncovered sand that had been loosely sprinkled on her body. The woman who found the body was a daily beach user and had passed the area several times without noticing anything amiss.

Teresa wasn’t tied or gagged and had no visible external injuries. She looked, in the words of one of the young detectives sent to guard the body, as if she was quietly sleeping.

The pathologist’s initial miscalculation about the time of the offence it seems came because where she lay, under overhanging heavy branches and foliage, acted like a natural refrigerator, because of extremely low overnight temperatures. The body had been perfectly preserved for eight days.

For the rest of the day, 10 detectives, rugged up in heavy jerseys and police jackets against the buffeting wind, crawled on their hands and knees, inch by inch, sifting sand looking for something – anything. No one touched the body, they just worked meticulously round it, chopping back the old tree to give a clear scene and recovering all foreign matter – old shoes, leftover food, lolly wrappers, glass, paper, corn cobs. It was all bagged, marked and taken away for further examination.

Ron Cooper won’t come right out and say it, but the specimen sampling of later suspects suggests that there was blood (not Teresa’s) and semen at the scene and a ginger pubic hair on Teresa’s body.

After six hours of clearing the site and directing 21 years of police knowledge onto the scene, Cooper allowed the body to be removed to the mortuary.

Next he attended a 3½ hour post mortem and insisted that his assistant Alan Aitken did too. “I didn’t want to go,”says Aitken, “It was very distasteful and upsetting, but it’s got to be done. There’s different ways of looking at things. We can ask the pathologist questions as he goes through, and it might just put a slightly different face on what he finds if we ask the right questions on the way through.

“It was bloody hard, it’s only the second post mortem of a child that I’ve ever been to. She looked like a little doll. It was very hard to believe she was dead. You had to keep saying to yourself this child has died at the hands of someone else. It made me very angry and I wanted to harness that.”

There is no pride, no dignity in a post mortem examination. After an extensive external examination, and photography of the body, taking an hour, it is opened from the throat to pubic regions. The chest and stomach cavity are opened and all internal organs removed. Everything is examined piece by piece, photographed if significant and pieces of internal organs are taken as exhibits. That takes another two hours.

Then the top of the skull is removed, the brain is taken out, weighed and sampled, and returned to the body with the rest of the organs. The head cavity is then stuffed with cotton wool, restitched, and after sympathetic make-up, the lifelike appearance of the body can often be disturbing.

“After that I just wanted to go home, hold my kids and never let them go,” says Aitken.

Again the findings of the pathologist are not for public consumption – not yet anyway – but they indicated to both Cooper and Aitken that Teresa was dead by lunchtime of the day of her abduction (because of the state of undigested food in her stomach) and that she had died at the beach of “manual asphyxiation” (not strangulation). She had also been “sexually assaulted”.

Ron Cooper had to tell Kelly Cormack how her daughter had died – he didn’t want her to hear it from any other source. And she cried then for the first and only time since he’d known her. He tried to get Kelly to view Teresa before she was buried, but friends had told Kelly to remember her daughter alive and happy.

“I tried to get her to say goodbye. I told her that Teresa looked beautiful. I wanted to show Kelly that she was peaceful. She wouldn’t listen and that saddened me. I wanted to try and make her feel that somehow it was all right.”

Cooper was sick and saddened and coldly angry. So where on earth did he begin?

ON TELEVISION detectives in leather jackets speed around in fast cars, asking pointed questions of suspects – sometimes with great menace. They always have the case cracked within the hour. The reality is so far removed from that as to be laughable.

Getting your ‘man’ is a long, laborious process, often tedious and always frustrating. It’s a process of going down an awful lot of dead-end roads, checking out what’s at the end and coming back to the point from which you started, often none the wiser. But every avenue has to be checked out. The most absurd and scatterbrained sounding tip-offs have to be investigated, because the detective never knows what information is important. It’s a job that could send you mad.

By the time Teresa’s body was found, the first of three area canvases was well underway. A growing band of detectives which would number 62 by the end of July was going door to door, covering a square mile area round the route the child was known to have taken on her last walk to school. But it’s not as simple as a quick chat to the person who answers the door. Each household has to be profiled: how many people live there, how many males in particular, were there any visitors to the house on June 19? What were the male members of the household doing between 8 and 11 on June 19 and can they prove it?

On that first series of visits 6,000 to 7,000 people were canvassed, and those that couldn’t account for their movements with alibis, went on a suspect list along with all known sex offenders in the Hawke’s Bay area and those who had ever been even questioned on child abuse matters.

On a second visit detectives had a list of suspect vehicles and showed residents a dozen photos of possible offenders, to try and jog their memories.

And on a third canvas which began in mid August, the focus was narrowed to 140 houses in the area Teresa was last seen alive. With an average two males aged from puberty to 83 per household, police took six weeks to ask each man 35 key questions, and identified eight “prospective offenders” who couldn’t be alibied.

Consider though the work involved in trying to trace just one suspect who has subsequently left the country. The man has been interviewed twice in recent years for allegedly interfering with young children – so he can’t be overlooked. Detectives interviewed his father, the Housing Corporation, Air New Zealand and the Auckland airport police (to check he did actually board the plane), his bank manager, a neighbour, the woman he sold his car to, the motor vehicle registry office, the Power Board, Telecom (for a disconnection date) and finally the Post Office for a possible forwarding address. There was one, but inquiries by Interpol have so far drawn a blank. Hours and months of work later that file still remains open.

At the same time blue Morris Minors were put under a scrupulous check. A car squad of up to six men spent four weeks checking out the owners of every blue Morris Minor from 1952 onwards registered in Hawke’s Bay – all 110 of them.

The 200 to 300 children at Richmond School and similarly-sized Maraenui School nearby were questioned – as much as you can question five to nine years-olds about the death of a fellow pupil; factories and business houses in Awatoto, Onekawa and Pandora, the main employers of the local workforce, particularly from central Napier were scrutinised for details of those who didn’t go to work on that day or those who started late; all taxi movements were checked on the morning.

Detectives were after not just suspects, but anybody who might have seen Teresa, or seen “anything” that was unusual on that day in that area.

In a joint attack another group of police interviewed all occupants of the 200 or so houses adjacent to Whirinaki Beach.

Whirinaki Beach is on the Napier to Gisborne road – a reasonably busy highway. Standing just above the spot where Teresa’s body was found, I counted 11 cars in five minutes at 11 on a Wednesday morning. There’s no reason to presume that it’d be any different on a Friday – so somebody must have seen something you’d think.

Police soon got to hear about the post office van that had stopped for smoko not far from the tree on June 19, the MOW road gang who were working at the other end of the stretch of road, and a couple who had stopped their car within metres of the scene, ate their lunch, and then went down on the beach.

Detectives got “very hot and bothered” about a man in a blue car seen acting strangely in the quarry opposite where Teresa’s body was found. He turned out to be collecting rocks for his rock garden and had walked right past the body. None of them saw a thing.

“In every inquiry there’s got to be an element of luck,” says Ron Cooper. “You’ve got to have your team organized 100 per cent, you’ve got to cover all angles and do the leg work, but there’s 10 percent of it that’s pure luck, that lucky break that suddenly makes all the pieces fall into place. We’ve waited and waited and it just hasn’t happened yet.

“I won’t give up on it, mind. In this business you’ve got to have infinite patience. And that piece of luck can come at any time.”

“On my last murder, in Wellington in 1986, we went for six straight days getting nothing on a guy who’d been strangled and thrown into the sea. It broke on day seven in a completely unexpected direction. We’d been right up the wrong alley, dealing with a street kid who reckoned she’d seen the offence. She was only having us on, but all these things had to be taken seriously at the time.

“Anyway on the seventh day two people came forward independently within half an hour of each other… One had seen the murderer leave with the victim and the other was a work mate who the offender had turned to for help. Those people had hung back either because they hoped we’d solve it without them, or their friends and families had told them not to get involved.

“Those are the sort of things you have to rely on. You have to hope that sooner or later you’ll get that lucky break. You only need one.”

A week after finding the body Cooper was feeling steady about his inquiry: “This one was never going to be simple, it wasn’t littered with clues. But I did hope we’d have it cracked within three weeks. If you’re practical, methodical, and thorough it should come.

“YOU’VE GOT to try and think your way into the head of your offender,” Cooper explains. “Putting all emotion aside – remember this is business – you’ve got to say why the hell was he there? What do we know about paedophiles, do they fit into a near, circumscribed format? Can you build a cubby hole for him?

“There’s a dearth of research in New Zealand, so we got the police in Australia to provide us with information on this type of offence in their country. We got some help from America and Dr Ian Miller, the coordinator of Psychological Services at Police Headquarters, Wellington, projected a profile for us.”

Teresa Cormack.

The following is a tentative offender profile drawn up after careful consultation between Ron Cooper and Ian Miller.

GENERAL: The literature on the subject of paedophilia (the act or fantasy of engaging in sexual activity with prepubertal children as a repeatedly preferred or exclusive method of achieving sexual excitement) notes that the condition is an overwhelmingly male phenomenon, and that it may afflict a significant number of persons in the general population. One authority considers 1 percent of the population to have a paedophilic orientation, but also commented that the vast majority of such persons never express these feelings in any overt form whatsoever, with their orientation remaining solely at the fantasy level alone. Of those who express their sexual orientation in physical acts, the greater majority restrict their activities to the touching or fondling of the sexual areas of their victims. A smaller group encourage their victims to touch them, or to masturbate them. Those who attempt to engage in actual sexual penetration, or close simulation are less common. The paedophilic offender who also commits homicide is the rare case, and has to be considered on an individual basis.

RACE: Most likely to be Caucasian.

AGE: Between 25 and 55 years.

RESIDENCE: Most likely local.

OCCUPATION: Semi-skilled employment with an adequate work record.

EDUCATION: Most likely to have left high school in the fourth or fifth form. Likely to have been in the lower to mid-stream.

RELIGION: Any religious affiliation will be motivated by his desire to alleviate his feelings of worthlessness and guilt to present a socially acceptable image of himself.

INTELLIGENCE: Average to below average.

MARITAL STATUS: It is quite likely that the offender is married or in a de facto relationship or is separated/divorced. He may have children of his own or step-children.

SEXUAL ORIENTATION: Heterosexual. He would be able to sustain adult sexual contacts but his interest would also be directed to children. Most likely to be a “regressed” type of paedophile. The regressed paedophile prefers adult partners, and becomes involved with a child when there is “some challenge to his sexual adequacy or threat to his sense of competency as a man”. His behaviour is atypical and as a result he is likely to be prone to guilt, remorse, and depression following the offence.

CLINICAL ASPECTS: A chronic paedophile, likely to have offended previously on several occasions. May also have minor sexual convictions for exhibitionism, voyeurism, obscene phone calls. He will show an inability to handle any stress in his life including physical problems and illness. His offending is most likely to be correlated to his reactions to stress, which would imply that he has recently undergone some disruption in his life, including such possibilities as a breakdown in his marriage or relationship, separation from a source of security, loss of employment, or some form of illness of a more chronic nature.

SOCIAL PRESENTATION: Inept and unskilled. Likely to show poor skills in interaction with adults.

INTERESTS AND HOBBIES: Because of its solitary nature, is likely to have self-centered interests involving a degree of solitude. He may take an active interest and involvement in activities with children.

PROBABILITY OF FUTURE OFFENDING: The offender’s paedophilic behaviour is likely to cease in the immediate short term, due to his feelings of shame, guilt, and the need to avoid drawing attention to himself. However, it is most likely that he will commit further offences of this type in the future, especially after the publicity surrounding this case dissipates. Also of concern is the knowledge that he committed the homicide in this instance, probably in response to the victim’s distress and desire to escape, and therefore in a future occasion he may well react in a similar manner, to the peril of his victim.

EARLY ON, Cooper found an ally in Ken Hawker, editor of the local evening paper, the Napier Daily Telegraph for 20-plus years.

Hawker knew the effect the Kirsa Jensen case had had on his city back in 1983, and he’d watched Napier’s 50,000 citizens go into “deep shock” in the days after the finding of Teresa’s body. He describes the public march down Emerson Street when 25,000 residents walked in total silence under a single placard “Protect Our Children” as “probably one of the most eerie moments of life.”

Hawker is a man who’s passionately keen on promoting Napier which he describes as “reeling a little like other rural centres, but we’ve got a good future.”

Realising that Cooper didn’t appear to be getting anywhere fast, Hawker went to him offering any help he could give. Within days the Telegraph had printed and distributed free of charge a four colour poster of a mannequin dressed to look like Teresa on the day she disappeared. These posters still stare down oppressively from lampposts and shop fronts around town.

And two weeks later the Telegraph ran a full page Teresa “checklist” full of maps and diagrams, trying to prompt the public memory. To that Hawker also added the paper’s editorial support instructing his staff to keep the story alive on the front page as long as possible. That’s when the information – some of it promising, some of it totally bizarre – began flooding in.

Going public for information on a crime opens the floodgates for every amateur detective, self-proclaimed psychic and those who are just plain “out to lunch” to quote the police vernacular. Buried in there among it all though might just be a relevant clue. “You put yourself in a Catch 22 situation where you look damned silly if you follow up some of these tips, but then you’re damned if you don’t,” says Cooper.

There’s a box of anonymous letters a foot deep in his office. Many of the letters are prefaced: “I don’t want to be considered a crank but . . .”They go on to list car registration numbers seen in dreams, suggesting looking in green sheds. There are lots of pencil drawings of suspects and, from one woman that regularly hears voices, the message “I’m in the boot Daddy, I’m in the boot.”

Other well-meaning citizens prior to the finding of the body had urged Cooper to “don’t forget they’re loading an Arab ship at the port, they’re well known for this type of abduction” and “consider that she was so pretty, someone might have taken her instead of waiting for an adoption.”

There’s been the vindictive element, of course, rushing to nominate suspects: ex-wives wanting a good property settlement or the upper hand in custody battles; and the kinky: one woman who nominated her 74-year-old boyfriend for being oversexed, another woman whose boyfriend continually dressed up in her clothing and another whose husband had suddenly started asking her to wear school uniforms.

Such well-meaning nonsense can be ignored, but anonymous notes like the one that arrived on July 21 reading simply: “Check all those on leave from Ohakea for the murder in Napier “can’t be. It took a dozen men nearly four weeks to alibi the 120 people on leave from Ohakea on June 19. “We check absolutely everything that has a chance of turning up the offender,” says Cooper stoically.

The most frustrating “dead end” was a phone caller from Palmerston North who diverted the investigation for three weeks. “He turned out to be someone who had an irrational suspicion of another person and wouldn’t deal with the police directly,” says Cooper. Finding that out was a mammoth task.

“A phone call was made by an anonymous woman to Richmond School in which she said she knew of a Maraenui mother who knew the offender. We put this in the media and put out a plea for the woman to come forward. Next a man called Palmerston North police saying that it was his sister who knew the murderer and that she was in danger – but he wouldn’t be identified. He said that there had been more than one offender and that a video had been made of the crime. He seemed to know things that he shouldn’t.

“It had the hallmarks of something we couldn’t leave”

Napier police finally managed to locate the caller – but it wasn’t easy. He’d told detectives that he’d recently been phoned by his sister and had called back again to check that she was all right.

Police seized all records of phone calls between Hawke’s Bay and Palmerston North – and using a team member’s home computer, called up any phone numbers where there had been reciprocal ring-back factors within a certain time frame. The computer made 750,000 comparisons and took 35 minutes to come up with the answer.

“In the end the guy was just a bloody dreamer and we lost three valuable weeks. I could have ripped his ears off, but you’ve got to go that far, you’ve got to see it through.”

Six weeks into the inquiry Ron Cooper got the one and only “break” he’s had and the key he believes will solve the case – eventually.

At that time the DSIR came back with a forensic report on material taken from the body and other exhibits found at the scene. Immediately he instructed his men to stop questioning Maoris. He becomes frustratingly vague again when asked what exactly the forensic evidence showed, but it seems likely that the light ginger colouring of the pubic hair found on or near the body would rule out the offender being Polynesian

From this point on all suspects who couldn’t be alibied by other means were requested to give pubic hair and blood samples – “plucking and sucking” in police parlance. Of 200 requests to the end of 1987, only three men refused to comply, although these three can’t be considered any more likely suspects than any of the others – despite “beaten up” stories to the contrary in the daily media, which have annoyed Ron Cooper no end.

Using the forensic evidence – whatever exactly it is – Cooper has managed to narrow those 200 down to 23 suspects who still can’t be positively ruled out. Scientific techniques in this country are only accurate to the degree that scientists can give a “comparable with” evaluation rather than an absolute yes or no on a specific suspect.

IN 90 percent of crimes where the offender hasn’t left some clearly identifying evidence at the scene, police can usually, relatively quickly, paste together a picture of both victim and offender’s movements from snippets of information provided by the public. The Cormack inquiry is significant for an almost total lack of such information. There’s still an hour and a half that can’t be accounted for.

“Once we’d completed the initial area canvas, which was an active inquiry, we were really in the hands of the public,” says Cooper. “At that point we just become passive recipients of information that we hope we can develop. We went to the papers and the television and whoever else would listen and said this is what we need to know, come and tell us. In this sort of case where initially we’ve turned up nothing, we’re totally dependent on the public and what they saw.”

The public had seen depressingly little. The Whirinaki woman who found the body remembered seeing “a man” on the beach sometime earlier in the week, but was unable to provide a single other detail of time or description. Two witnesses came forward to report driving past the beach on the 19th. One man in the car noticed what he thought was a man and a girl on the beach while the other reposted seeing an “old model, English-looking cut down truck with a home-made canopy on the back.”

Police became excited, fed the information to the national media and sat back while 330 such vehicles from Invercargill to Auckland were nominated as “possibles” by the public.

Cooper and his men regarded the trucks as their strongest lead and tore into trying to track it down, but after two months of checking by police all around the country, they had to concede that they may have actually been looking for a vehicle that didn’t exist.

A week later another motorist came forward and reported seeing a girl and a man on the beach at the right time, but this description was at odds with the first. More frustration.

Then came the Datsun Sunny. At 10am on June 19 a woman driving from the south into Napier stopped at the Wairoa Road intersection (which is a major turn off from the Napier Road to the Whirinaki Beach Road). While waiting to turn, she noticed an early model, light blue Datsun Sunny pass in front of her. She noticed a child, not restrained, in the front seat, and was angered, but she didn’t see the driver. She did, however, notice the car had a special badge on the front grill.

This meant another month’s work tracking down all the 79 to 83 Datsun Sunnys in Hawkes Bay (85 in Napier/Hastings and 55 from Gisborne to Dannevirke). An exasperating search – also to no avail. “God we’ve been so unlucky on this one,” laments a young detective on the car’s file. “If the woman could remember the model of the car, if she could get hot and bothered about the kid being unrestrained and she could notice the badge on the car, why oh why couldn’t she have cast her eyes over the driver. It makes you want to weep…”

Along with the cars and the very few reported sightings, come the public “nominations” of possible offenders – nearly 800 of them by the end of last year.

First there are the possibilities plucked from police files because of previous convictions or suspect behaviour, then there are those the Social Welfare Department suggests may be worth a look – and then there are the 70 to 75 percent who have been nominated by Joe or Jean Person.

“There have been a lot of skeletons rattled in the cupboard on this one” says Cooper. “We’ve had teachers, businessmen, painters, plumbers, ministers of religion nominated. We’ve had mothers suggesting their sons, sisters nominating brothers, platoons of wives suggesting former husbands, some women even nominating present husbands. It’s remarkable too how many times one man is nominated by a number of people who don’t know each other – and we invariably find there’s no smoke without fire.”

A lot of Cooper’s time has been spent behind a desk directing and dispatching his troops. At all times he has a file at hand reading over and over the paperwork on suspects. “The things that these people have done to their own would make you sick.

“I’ve certainly changed my awareness to the depth of the problem of sexual abuse of children. abuse of children. Initially I was quite sceptical about some of the facts and figures that are put about on incest and child sexual abuse. It was not my experience as a policeman, father or citizen. But the more I read the files the more you realise that children can be lifelong victims. When you extract this information and put it in one place it’s truly frightening. In Napier there are only 50,000 people but there are dozens of men with previous convictions for incest and sexual assault. It’s not often that you look at that part of the community. We’ve taken the lid off Napier in search of one type of man, and what we’ve found is hideous.”

He’s referring to a large number of women who have come forward detailing incidents of incest on themselves or their children by fathers, husbands, brothers or friends of the family, incidents which have never been reported because of shame and the prospect of public stigma.

“Enough of these women have come forward to convince me that they’re not lying and that this problem is much bigger that I could ever have imagined. We’ve had to overlook an awful lot of crime and nastiness on the way through.”

Nastiness like the six-year-old Napier girl who turned up at a Gisborne health camp with vaginal and anal injuries so bad that she had lost control of her bowels.

“She’d been hideously abused and we did charge a friend of her family on that one. But most of that you have to put aside. It’s important in a big inquiry to keep your mind fixed on just one offender.”

ENTERING RON Cooper’s office in the latter part of the inquiry, now relocated to Napier’s main police building, is to realise how poorly the police treat their workers in terms of their working environment.

It’s a depressing place with tatty brown carpet squares on the floor, maps tacked roughly to the wall and files stacked dozen upon dozen climbing the walls. There’s also a photocopier, a computer terminal link with Wanganui, and three policemen and one woman clerk sharing the same space. Ron Cooper earns $48,000 a year but for all that he may as well be working in a factory.

To the left of his desk is sufficient space for a small placard which could be his motto. It reads: “Age and treachery will always overcome youth and skill.”

Smiling down upon this scene of organised chaos is a large framed portrait of Teresa. “She’s not there to intimidate,” says Cooper, “She’s there to inspire: She’s our client. We’re doing all this for her.”

Inspiration is something that Cooper has had to work hard at as the months have rolled by without breaks. A few of his men have suffered crises of confidence but he’s full of praise for the teamwork that’s gone in so far. The admiration is reciprocal. Cooper’s workers say he’s a top man. “We’d go to hell and back for him,” is how one young detective puts it.

The inquiry though is only as sound as its weakest link. Some of “the boys” are from out of town – pulled in from Hamilton, Tauranga, Rotorua, Auckland and Wellington. They’re missing wives and girlfriends. Even the single ones who’ve been getting drunk and creating havoc down at the Masonic Hotel (renamed during this inquiry the Caravan of Love after a current hit record) are thinking about going home, wondering when it’ll all be over. They’ve been chasing dead ends for five months now. It must be hard.

Daily Cooper strokes, chivvies and cajoles them in a 45 minute round table conference, going over and over and over the same ground. He’s quietly severe with his·men. He doesn’t yell. He doesn’t have to. They know when he’s not pleased. But he has to keep their spirits up. If they let up, go easy, cut corners just once, then Cooper can kiss it goodbye forever and that may mean another child will die. The offender profile suggests this man will sooner or later re-offend – he can’t help himself.

The collation and storing of the information gleaned in the thousands of hours of work put in by these detectives, is crucial. So it’s astounding to find that the computer age hasn’t come to the police yet – or at least not to this inquiry.

Across the corridor from Ron Cooper’s rabbit warren is a five by three metre room lined entirely with large ring binder files with “Cormack Inquiry” scrawled across their spines. This is the information centre manned by Alan Aitken and a clerk, Constable John Dean.

Here in three wooden boxes filled with 6,000 pieces of card is the inquiry. Drop the box and you’re dead. Every man, woman and child of any importance who’s been talked to, has a card file and they’re all cross referenced. The card index system has been used for most major crimes in this country for the past 30 years and it works, says John Dean, but it’s often slow and cumbersome – a system belonging to the Dark Ages.

He should know. Dean – “Dino” to all involved in the inquiry – has another identity outside the force. He owns a company Solid State Electronics which designs and manufactures control systems for small stand alone computers. At the moment he earns around $25,000 a year as a policeman and his company turns over $30,000 annually.

When he got to his 2000th piece of card and the suspect list was nearing 300, Dean brought in his own $15,000 home-built computer and began feeding the suspect profiles into that.

“It made so much more sense to have the suspects on the computer,” says Dean. “I’d have people coming to me asking ‘what was the name of that guy we talked to at such and such an address?’ It’s the sort of thing that could take two to three hours manually – if your memory serves you well – and three seconds on the computer.”

Dean isn’t being paid any extra for his computer expertise or for the use of his machinery. It’s a labour of love. The inquiry, it transpires, was offered free of charge a complete computer system similar to one that had been devised in England for the Yorkshire Ripper murders inquiry, and had to tum it down. The reason: Although Headquarters is fully computerised, they wouldn’t loan Napier a computer or allow them to take up the offer because the computer offered was a different brand from those purchased and approved by HQ. Small wonder then that Wellington head office is referred to widely as “bullshit castle”.

IN MID-NOVEMBER after an out-of-town detective inspector has gone through the file to check that Cooper has done everything possible with the leads he’s got, and after consultation with Wellington, the decision is made to scale down the inquiry, to return Cooper to Wellington and to leave Aitken supervising tail-end investigations. Nobody will say it, but this is the turning point, the time to acknowledge that this may remain an unsolved crime.

Flying into Napier in his last week there is a gaunt tiredness about Ron Cooper. He’s given it his best shot and so far he’s failed. Lines etch his face and although he celebrated his 38th birthday just weeks ago, right now he looks like he could be 48.

As the Friendship banks steeply over the aerodrome the Awatoto fertiliser works and bridge flicker momentarily across our view. Those are the landmarks of Napier’s other police shame – the still unsolved Kirsa Jensen case.

They work on Cooper like a theatre prompt: “It’s so frustrating to know that I’m going away from daily contact (with the case). It’s much less likely to crack then… It’s always nice to win. You have to look at it as failure tempered with the realisation that you can only do so much. But you always wonder if there was something more that could have been done, something you could have done better.”

In this week Cooper will do book work, write final reports and spend his last nights in the Edgewater Motel, a pleasant but impersonal two storey concrete block edifice down on the waterfront. He even manages to squeeze in a night of deer stalking – sitting in the hills until lam when cold defeats potential loss of face – and he has to concede that the much talked about venison for dinner is not going to eventuate – not on this inquiry anyway.

This will also be the last week he’ll have to do his own washing and prepare his own dinners – the police allowance of $53 a day for out of town assignments doesn’t stretch to restaurant meals.

When it comes to writing down what Ron Cooper actually knows about the offender, it’s a slim book “We know 23 people who it might be and 800 that it isn’t, so we must be further ahead,” he says with a wan smile.

On a more serious note Cooper reckons that there are people in New Zealand other than the offender himself who are either withholding information, don’t realise the value of what they know or don’t want to harm someone. His gut reaction tells him that despite five months of work the inquiry hasn’t come to the offender yet – “and I don’t think we’ve gone past him without recognising him. I also believe in my heart of hearts that he’s a local. If you put a pin in Teresa’s house, the offender will live within 500 yards to a kilometre. That’s my bet.”

So how does he feel about spending so much time and still to be hypothesising. “Disappointment. A feeling of extreme disappointment. First because we haven’t solved it for the victim and her family, second because the investigation team have given their all and third, of course, for myself. We all like to be winners,” he says matter-of-factly. After several days spent close to Ron Cooper and a number of weeks following up on his inquiry, I’ve come to the conclusion that he’s not a man anyone is ever going to know very well. His replies to probing questions are as clipped and in order as his walrus moustache and dark hair, now liberally sprinkled with grey.

Policemen, it seems, work hard at keeping their feelings in check – and Ron Cooper has had 21 years of practice. His wife Colleen says there’s only one time she’s seen him crack. That was on Christmas day 1976 when his youngest brother shot himself with his father’s hunting rifle, over a marriage gone wrong. After that it seems Cooper has been determined that nothing will ever hurt him again.

On my last day in Napier I visited the Wharerangi cemetery, a peaceful valley sloping down a pine and gum-covered hillside to the west of the city. Cooper was ill at ease as we inspected the grave without a headstone where the grass still hasn’t come out of the clay. I asked if he came here often as some sort of inspiration. “No, I hate cemeteries. She’s dead, she’s in the ground and she shouldn’t be. That’s all I’ve got to remember – and then get on with the business.”

Do policemen ever cry, I wondered out loud? “Yeah,” he said, escaping to the police car, “but they’d never admit it.”

ON NOVEMBER 27, after 12 weeks of driving to and from Napier after weekends with his family, and another eight of flying in every Monday morning on Flight 806, Cooper hands over the inquiry to Aitken and after speeches, and a “bit of a bun fight” in the police bar, he farewells Napier.

He’ll miss Aitken. “Your 2-i-c is your right hand man. You enter into a relationship similar to a marriage. There’s a deep commitment there. For the past five months neither of us has made a move or come to a decision without consulting the other.”

So what not? Chief Inspector Bruce Scott, district commander for Hastings and Napier is one man who knows intimately what Cooper and Aitken will go through in the next few months. He was an Auckland detective inspector in charge of the unresolved inquiry into the Henderson murder of schoolgirl Tracy Ann Patient. “That feeling of failure lasts for a long time, they’ve got my sympathy,” he says.

Scott remembers January 29, 1976 like yesterday. “You never give an unsolved inquiry away, especially if you’re the guy carrying the can.” To prove a point he reaches for his bottom drawer and removes a large hardback file book. Within, there are pictures of Tracy, pages of notes and diagrams of a key clue, a broken signet ring. Smiling he adds. “You can’t let your failures get to you. And Ron Cooper should take heart, that black mark doesn’t seem to have hindered my career.”

For Alan Aitken life will proceed pretty much as it has for the past five months. He’s owed 105 days of holiday (the police don’t pay overtime, they just give their men a day off for every extra day worked) and he’ll take 10 days between Christmas and New Year. And throughout that break he’ll continue to wake in the middle of the night tossing the case around in his head – mental gymnastics he calls it.

In the days after Cooper leaves there’s a steady trickle of suspect nominations as the inquiry rolls on.

In mid-December he gets “quite excited” about a man living in Opotiki who was a Napier resident at the time of the offence: “He looked really impressive on paper, so we went and shook him out, but it came to nothing.”

In the weeks up to Christmas, Dr Graham Dick from the chemistry division of the DSIR in Wellington returns from England, where he has taken forensic examples from Teresa’s body and the murder scene. Complex DNA testing on these samples, police hope, will be able to, finally, eliminate the 23 suspects who have not been able to be alibied.

This highly accurate chemical identification system, which has recently been accepted in England for the first time as irrefutable evidence in a murder trial, should also give the police the scientific evidence needed to convict the killer if and when he is located and blood tested.

Also as Christmas looms, Aitken starts to go through history books. From Wellington he gets a computer print-out on every person ever convicted of a sex-related offence in New Zealand since 1910 – that’s 695 pages plus an extra 399 pages of rapists or attempted rapists. He gets 260 prospects by selecting from the last 20 years the men living in Napier and Hastings. Ten have already been nominated but that leaves 250 new possibilities. He says it’s not clutching at straws – just being thorough.

In March or April, Aitken thinks he’ll probably have to return to his post as head of Hastings CIB. The inquiry will be scaled right down, the box of cards will go in a side drawer. “It’ll be out of sight, but never out of mind. If it goes unsolved it will always be on my mind. It could become an obsession…”

WIth hindsight he believes the Cormack inquiry will probably be the biggest “highlight” of his career, and the biggest “smear” on his record.

BACK AT the Lower Hutt house with the neatly trimmed lawns, the board fence and a new police-trained Alsatian dog called Chad, Ron Cooper slops around in blue shorts, hot pink tee shirt and jandals, working on putting his life back together.

At 8am, on the morning after his arrival back from Napier he began ripping the kitchen to pieces and rebuilding it – a promise he’d been making to Colleen since the early days of winter.

But redesigning the house and restructuring a family are two different things. There’s a lot that’s changed since that Saturday night call. Colleen, who’s always put her husband’s career first, has a new found independence. “I’ve done my fair share of head breaking on this inquiry. I’ve yelled ‘what about me?’ a few times”

“But she’s also learned to make the best of the loneliness and the absence. Around her part-time job as a teller at the ANZ Petone, she’s fitted interclub badminton, regular jazzercise and several real estate exams. She’s learnt a lot about herself in the past five months. Now Ron Cooper has to find out those things too.

Daughter Ellen has been the easiest to please. She follows her father like a shadow, pleased to have him home for a cuddle every night. Son Daniel has taken the first steps from boy to man while his Dad’s been away. He’s been the one Colleen has turned to when things went bump in the night, he organised the collection of the winter’s firewood from the banks of the Hutt River and he’s negotiated School Certificate without Ron’s guiding hand. Now he must begin re-establishing that tenuous relationship with his father.

There’ve been good sides of the separation. It’s made the whole family realise just what close friends they are.

It’s also meant for Ron Cooper, for the first time in 17 years of marriage, has started buying his wife gifts. “They’re so macho in the police force,” Colleen mocks. “I was amazed one weekend when he came home bearing French perfume. This is the same man who when I sent him flowers for our 15th wedding anniversary gave them to the typist he was so embarrassed.”

After Christmas spent in Nelson with the family and his parents, Ron now looks forward to returning to work in mid-February, and also to getting back to fitness.

After Christmas spent in Nelson with the family and his parents, Ron now looks forward to returning to work in mid-February, and also to getting back to fitness.

Carrot juice and yoghurt for lunch and 80 miles a week will be the new regime as the Rotorua marathon looms on April 30. It’ll be his fourth crack at New Zealand’s toughest marathon. His best time is three hours 23 minutes finishing just seconds in front of Napier’s Barry Hunter.

Professionally though, Cooper doesn’t know where he’s going this year. He’ll return as detective inspector in charge of general and fraud squads to Waring Taylor Street, Wellington, but he’d like a change. He’d like the challenge of being detective inspector in charge of a provincial city somewhere – and there’s a possibility such a post will come vacant soon in Rotorua.

“I’d like a North Island post. We’re after lifestyle really. A chance to consolidate as a family and enjoy life. I’m eligible to retire at 50. I’d like to get settled somewhere, so Colleen can get into some sort of business. And then who knows…”

Wherever he is, there’s little hope of Teresa Cormack being far from his mind. “Every day’s a new day, but she’s always there, never far from my thoughts.

“It haunts me, it’ll always be with me. It goes on your record, you know. There’s a list of unsolved murders. But I’ve told them to put my name down in pencil…”