Legacy & Loss / Vintner’s Luck

He’s spent a lifetime bringing good times and good wines to the New Zealand people, and played a pivotal role in developing our wine industry, yet a disastrous set of events has seen Sir George Fistonich lose the family business he built and left him feeling betrayed and bitter. Joanne Drayton tells his story.

By Joanne Drayton

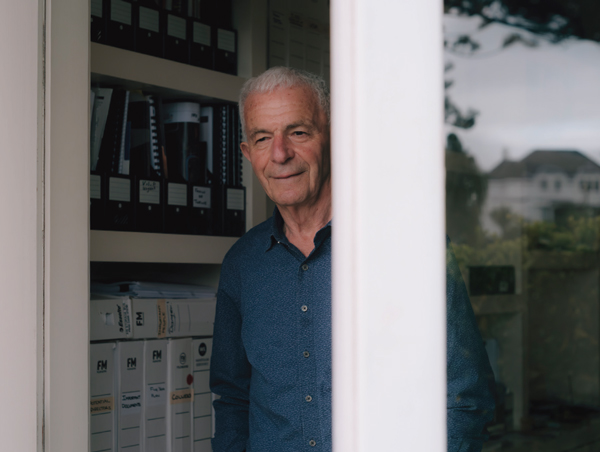

Stepping into Sir George Fistonich’s house looking out over Hobson Bay in Auckland’s Parnell is like walking into his mind. An amateur shrink himself, he has analysed people successfully for decades. Equally, his own head, and everything in it, is testimony to his granite will, toughened by time and pressure, his molten ambition and almost clairvoyant vision for the future.

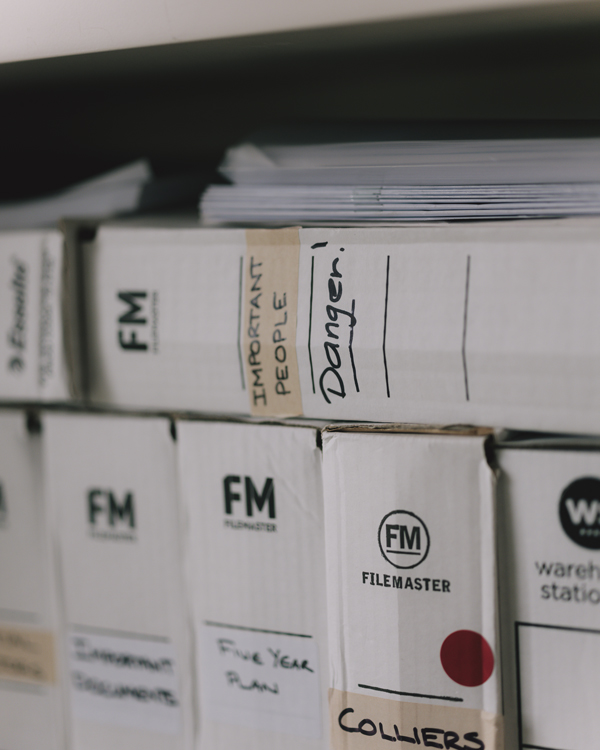

Aspects of Sir George’s psyche are everywhere in his home, which is now the central nervous system of his wine empire. Entry to its working heart is a meeting room dripping with awards: golden cups; gold medals enough to sink a Spanish galleon; certificates galore; and international prizes — all for winemaking excellence. Annexed to this is a smart little library, then down a small flight of stairs is his home office with an expansive desk, rows of plastic drawers full of stored archives, and bulging shelves of resource boxes. One of the boxes is labelled “Important People” and “Danger!”

These are the collected memories of Sir George’s lifetime. Put together, in his home, they tell a private story of stellar achievement. But each of Sir George’s golden moments intersects with a public event in the history of New Zealand’s wine industry. His story is our story of wine culture. His memories of the evolution of Villa Maria from a few vines in the backyard to a multi-million-dollar wine industry, are shared memories. Sir George’s choices changed Kiwi taste, access and patterns of wine consumption. He was maestro to our orchestra, so his pain at losing the Villa Maria brand in 2021 inevitably touches us.

Buried deep in that repository of Sir George’s home archive is his family’s DNA. Andrija Fistonich, his father, came to New Zealand in 1926, a Croatian immigrant from the bone-breakingly, breathtakingly poor village of Zastrazisce on the island of Hvar, off the coast of what was then Yugoslavia. Years later, in 2001, Sir George and his wife, Gail, travelled to meet a cousin in Croatia. The land there was barren, the living primitive, and cooking was done on an open fire in a stone shed separate from the cottage. In the 1920s, Andrija saw New Zealand’s potential. He worked at a quarry on Rangitoto; in the gumfields of Northland; labouring at a drainage scheme on the Hauraki Plain; as a freezing worker; and finally on the Auckland wharves.

Masses of business files, awards and medals, along with cuttings of news stories and magazine profiles document Sir George’s lifetime in the wine industry.

In 1935, he married Mandica Banovich, and they had four children, Elsie, Ivan, George and Peter. Like many Croatian families they toiled tirelessly to own their own land. Money was hard earnt and always short. Holidays were few. Reading was frowned on. Sport was considered frivolous. Work fuelled the engine of the immigrant dream. Croatian austerity was punctuated by exuberant community get-togethers. Families feasted at luncheons and dinners, drank their own homemade wines and spirits, and argued over card games late into the night. Men shouted heatedly in mostly raucous fun, and women served at the table.

One of the inexhaustible topics of conversation was who had the best vintage, and the best advice on how to achieve it. Croatians saw wine as being intrinsic to the meal. Wine for sale to others was a natural extension of catering for their own needs.

When Andrija and Mandica Fistonich finally saved the 500 pounds needed to buy five acres on Kirkbridge Road, in Māngere, the block was quickly converted to produce a modest income. The Fistoniches ran cows, planted fruit trees and a market garden, and kept an acre aside to grow grapes. Things were lean, still, and the children were sent out to forage for wild mushrooms to sell. And their labour — weeding, planting and pruning — was crucial to keeping the family business afloat.

Patriarchs traditionally dominated Croatian families. The imposition of strict hierarchies of gender and primogeniture were an extension of culture and chauvinistic control. Elsie, the Fistoniches’ only daughter, was destined to marry, and Ivan, their eldest son, to go to university and become a lawyer. George, the second son, was marked for a trade, which he began at 15 years old, when he left De La Salle College in Auckland. There was angst for the young George in the predestination of Andrija’s customary, yet also financially expedient, decision. He envied the education his brother was automatically given, but more than that he wanted — not a trade — but to own his own land and to cultivate grapes.

So, the challenge was laid down, and George finished his five-year builder’s apprenticeship at H J Short & Company in the record time of just three years and 10 months. He was free now to realise his dream of becoming a viticulturist. Andrija was again resistant. Once more young George’s smouldering ambition pitched him against his father’s will. He worked part-time at the Fistonich vineyard, and for Montana, a fledgling wine company owned by his sister, Elsie, and her husband, Frank Yukich. To build funds and supplement his vineyard work, George laboured on building sites and on-sold cars and motorbikes.

His memories of the evolution of Villa Maria from a few vines in the backyard to a multimillion-dollar wine industry, are shared memories. Sir George’s choices changed Kiwi taste, access and patterns of wine consumption.

After losing Villa Maria, decades of office files have come to be stored in Sir George’s family home.

George’s threat to buy his own acreage at Clevedon was circumvented by his father’s early death. Ultimately, George and his young wife, Gail, moved into the property on Kirkbridge Road and George’s life in the wine industry became a reality. He always liked the idea of Villa Maria as the name for a label. It would resonate in people’s minds, he believed, with things European, and therefore feel exotic.

Wine itself was a foreign concept to most New Zealanders in the 1940s, 50s and 60s. Women, on the whole, drank modest quantities of sweet, sticky, fortified ports and sherries, which were largely imported and very expensive. Real men, on the other hand, drank beer. Drinking was generally done in the public house between the end of work and the last drinks served before the bar closed at 6pm. Men stumbled home in varying states of intoxication. Draconian liquor laws inspired by the temperance movement were still in place and used by large aggressive breweries to dictate what, where and when you could drink.

Regulations around the consumption of alcohol and food overflowed into the world of public dining. As late as the 1960s, restaurants in New Zealand were unable to serve liquor with food. So, Kiwi restaurants remained dry zones and the pleasurable link between food and wine was not established. Eating out was rare and the majority of it was done at the nearest pie-cart or around Formica tables, seated on tubular steel chairs with vinyl-covered seats in the sit-in section of the local fish and chip shop. Atmospheric extras such as a fly eradicator, white neon strip light, faded poster of New Zealand coastal fish, and a dusty vase of pop-together plastic flowers were common.

Any change in the pattern of Kiwi alcohol and food consumption would have to be systemic — legal, as well as corporate and cultural — and this was Sir George’s biggest challenge yet.