Four Corners

NELSON

The forgotten earthquake

Replanting a kelp forest, a quake detective’s surprising discoveries, why we can expect a subtle shift in our foreign policy, and more.

By Paul Gorman

Thursday 10 December 1925 is a day the collective memory of Nelson should, you might think, remember well.

Wednesday was an unremarkable summer’s day in Nelson — cloudy and mild, with temperatures reaching about 19 degrees, according to the Cawthron Institute’s weather station.

As dusk fell, the overcast veil of cloud and haze showed no sign of clearing and the warm northerly breeze continued into the night. Suddenly, at 1.15am on the 10th, the silence was shattered by the rumbling earth. As the ground started pitching and tossing, the noise of smashing glass and glassware and crockery, of chimneys collapsing and masonry falling, added to the din.

After more than half a minute of shaking in some places, the earth slowly settled, leaving residents dazed and scared, and picking through wreckage. A telegraph officer in Nelson reported the earthquake lasted “25 seconds. Violent portion about 5 secs … A rumbling noise before shock & continuous light tremors for 10 secs before & after the violent portion of the shock.”

It was not just Nelson rudely shaken from sleep. The earthquake was felt widely across central New Zealand, in fact from Auckland to Dunedin.

A roughly repaired Wellington headstone provided evidence for an earthquake investigator.

On the other side of Cook Strait, a similar report came from the Wellington wireless station: “23 seconds. A continuous rumble of nearly 15 seconds caused agitated swinging of suspended electric light shades and general rattling of the building, and immediately following this a heavy shake of 7 to 8 seconds’ duration causing creaking of the building. A cat asleep on the floor was very much startled during this.”

A 75-year-old widow in Taihape reportedly died of a heart attack during the earthquake. Chimneys fell throughout central regions, especially throughout Marlborough, and a war memorial in Cheviot, North Canterbury, was cracked. The lighthouse at Farewell Spit received minor damage and household contents were broken in Pātea, Collingwood, Eltham and Ohakune.

In Wellington, the early Thursday quake caused bells on the main post office to ring out, while the shafts of electric lifts in some buildings shifted by a couple of feet.

And the “handsome old Celtic cross, which was raised over the tomb of the late Rev Fr O’Reilly … came to grief. The cross broke from its pedestal, and in falling to the ground was broken into pieces,” The Dominion reported.

One enterprising Nelson brickie was very quick off the mark, with a front-page classified advertisement in Thursday’s Nelson Evening Mail: “EARTHQUAKE. Chimneys repaired at shortest notice. Phone 482. — A. Stratford. Bricklayer.”

There were also aftershocks, with a particularly strong one felt in the capital, Nelson, Havelock and Kaikōura at 3.18pm on Saturday 12 December. Pinpointing the details of earthquakes a century ago is not as easy as it is today, due to the advancements in science.

The best estimate is that the 10 December 1925 earthquake was of about magnitude 6.5 and occurred about 70km deep near French Pass in the Marlborough Sounds. It is bizarre that such a significant quake never made it into the history books. As a result, it largely disappeared from memory — until a young and intense earthquake enthusiast started piecing things together.

According to the plate on his coffin Fr Joseph Jeremiah Purcell O’Reilly, Wellington’s first resident Catholic priest “died a happy death” on 21 July 1880, aged 80.

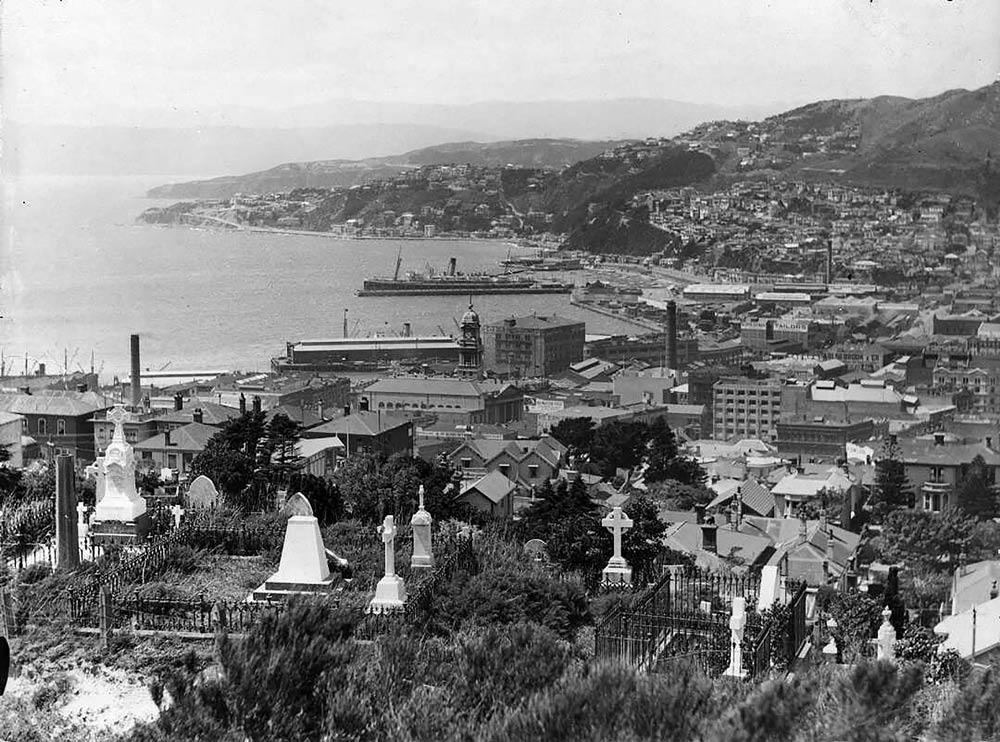

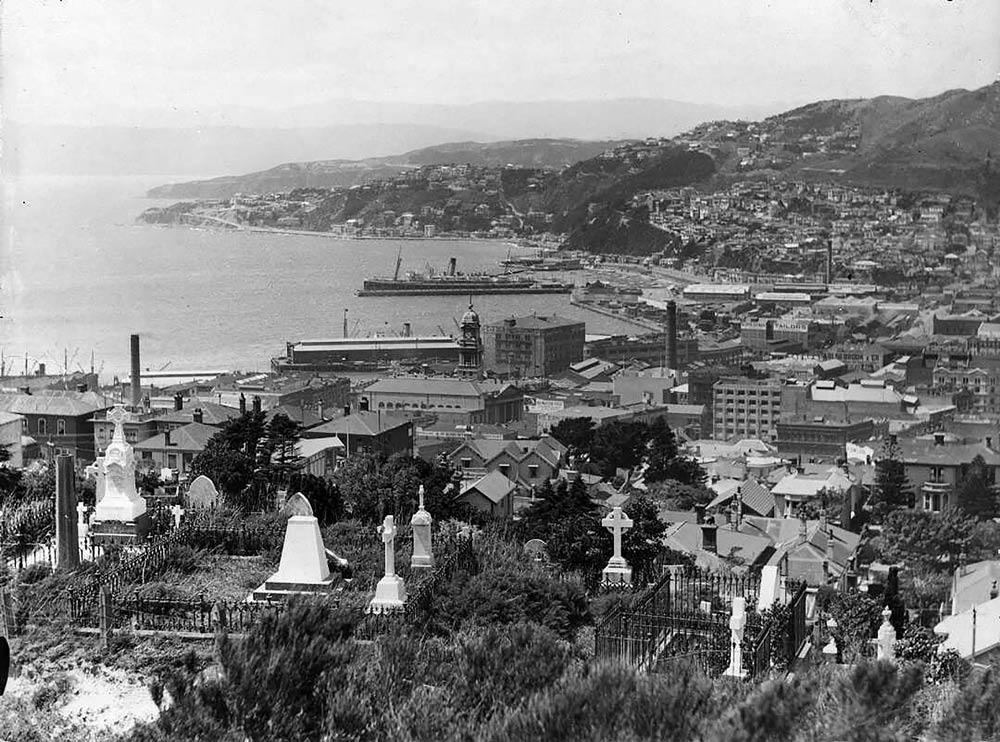

His crudely repaired headstone is believed to be the sole remaining piece of evidence of a damaging and forgotten earthquake accidentally rediscovered by a visiting English seismologist, Jamie Gurney.

“I don’t know precisely how long the cross was down for, somewhere up to about 14 years, but they did a terrible job patching it up with horrible concrete.”

Celtic harps on the bottom of two sides of the marble cross where it joins the plinth were also wrecked in the repair work. “There’s a picture from 1930 in the National Library archives and it shows, looking down from what’s now Vic Uni, the pedestal just standing on its own, and you can see the cross down on the ground behind it when you know what you’re looking for.”

Gurney, 27, is in New Zealand researching historical earthquakes with GNS Science in Wellington. He fell in love with New Zealand on a family holiday early in 2010 and studied the two Clarence earthquakes of 30 April 1925 for his University of Portsmouth MSc degree in geological and environmental hazards.

As @UKEQ_Bulletin, he tweets frequently about old and new quakes, and is highly knowledgeable about Aotearoa’s shaky ground. Gurney stumbled across the 1925 Nelson quake while writing his MSc thesis.

“While looking at the 1925 Clarence quake, I checked the GeoNet search for the same year and found the 28 November Marlborough quake and the 10 December Nelson quake — classified as ‘Motueka, M5.5, 25km depth’ — on there.

“Once I’d found Nelson on GeoNet, I used Papers Past to check it out, and then the ‘felt-report’ cards. When I saw a felt report from Dunedin for the ‘Motueka’ quake, I knew it could never be magnitude 5.5, 25km deep near Motueka, and shook my head in disbelief.”

GNS Science had provided Gurney with a batch of felt-report cards for 1925, which in those days were handwritten by postmasters, schoolmasters, lighthouse keepers and weather observers after earthquakes, before being sent to the Dominion Observatory in Wellington for analysis and filing.

“I had a look through the whole of 1925 and, as I kept looking, I discovered there were actually eight damaging earthquakes that year. That really struck me, as I don’t know if there’s any other year in colonial history where there were so many damaging earthquakes, all largely unrelated.

It seemed the December 1925 earthquake had been lost in the noise of the larger 17 June 1929 Murchison/Buller quake, of around magnitude 7.7-7.8, which killed 17 people and caused huge damage across the top of the South Island, triggering landslides, destroying homes, roads and bridges.

“1925 was a very active year and the top of the South Island in particular got shaken a lot, five times, not including some of the aftershocks as well.

Mount St Cemetery and Wellington Harbour, around 1930.

Museum research assistant Jeanette Ware dug out what she could find on the December 1925 quake for North & South, as she had done for Gurney two years earlier. She found mention of the earthquake, and of others that year and the following, in the diary of high-profile Nelson College schoolmaster Frederick Gibbs. He was an advisor to well-known botanist Thomas Cawthron, and was heavily involved with the Royal Society of New Zealand’s astronomical branch and the Nelson Observatory. But apart from Gibbs’ records there was very little other evidence the earthquakes had occurred.

The largest earthquakes are burnt into the memory of New Zealanders from school history lessons. But Gurney says the lack of comprehensive and robust earthquake reports, and the rudimentary nature of seismographs and their recordings, has made it difficult to accurately determine the magnitude, depth and location of earthquakes which occurred close to and more than 100 years ago.

At the time of writing, Gurney had never felt an earthquake, but says he wants to before heading home later in the year, “as long as it isn’t too large and scary”. While at GNS Science, Gurney is investigating six earthquakes of between magnitude 4.5 and 6.0, which shook Taranaki in 1882, 1902, 1903, 1925, 1927 and 1928. The most recent damaging quakes in the region were about magnitude 5.0 in 1938 and magnitude 4.5 in 1942.

It seems a harsh question to ask, but what’s the point of researching old earthquakes?

Gurney is quick to answer: “It improves the completeness of our historical record. New Plymouth is regarded as quite low seismic hazard, compared to places like Wellington and Napier. So for Taranaki, adding another five damaging quakes to the record will improve the seismic hazard estimates for the area, and improve the building codes.”

Similarly, the extra knowledge about the December 1925 Nelson quake will help with the understanding of earthquake risk in that region.

Gurney hopes his work has put the Nelson quake in its rightful place among the larger events in New Zealand’s seismological history. “It’s pretty strange really for a magnitude 6.0-plus earthquake to have been flying below the radar.”

By Paul Gorman

This story appeared in the June 2023 issue of North & South.