Running Man

As hopes build for the latest crop of New Zealand athletes, one of the stars of a golden era for the black singlet is still running — and still has stories to tell.

By Dylan Cleaver

When he was four years old, Rodney Dixon snuck out the gate to his home and ran two kilometres to Stoke School to join his brother John.

He hasn’t stopped running.

“I was born to run,” says Rod Dixon from his home in Nelson. “I played rugby, cricket, hockey and soccer, but I never got the same feeling as I did when I was just running. On the day I turned 12 I joined my local running club and that was it.”

Dixon loved the purity of a running race: you turned up to the start line, somebody shouted “Go!” and you ran like the clappers to a fixed finishing point.

A fidgety, easily distracted kid, Dixon benefited from an understanding teacher, Graham Leversedge, at Tāhunanui School who recognised his pupil’s kinetic energy and would send him off on frequent, and possibly pointless, jobs delivering notes to classrooms on the other side of the school.

Dixon loved the portability of running: you just needed a pair of shoes to attach to a pair of legs (and sometimes, when you lived near the beach like he did, you didn’t even need shoes).

He grew to love the lineal aspects of New Zealand middle-distance running. Talk to Dixon — and when you sit down to talk with him you need to be prepared to do a lot of listening — and he delights in drawing straight lines between Jack Lovelock and Geordie Beamish, New Zealand’s latest track star. It’s a line that passes through, among others Harold Nelson, Murray Halberg, Peter Snell, John Davies, Marise Chamberlain, Dick Quax, Dick Tayler, John Walker, Anne Audain, Lorraine Moller and Nick Willis. Each name can divert him onto another branch of running’s family tree.

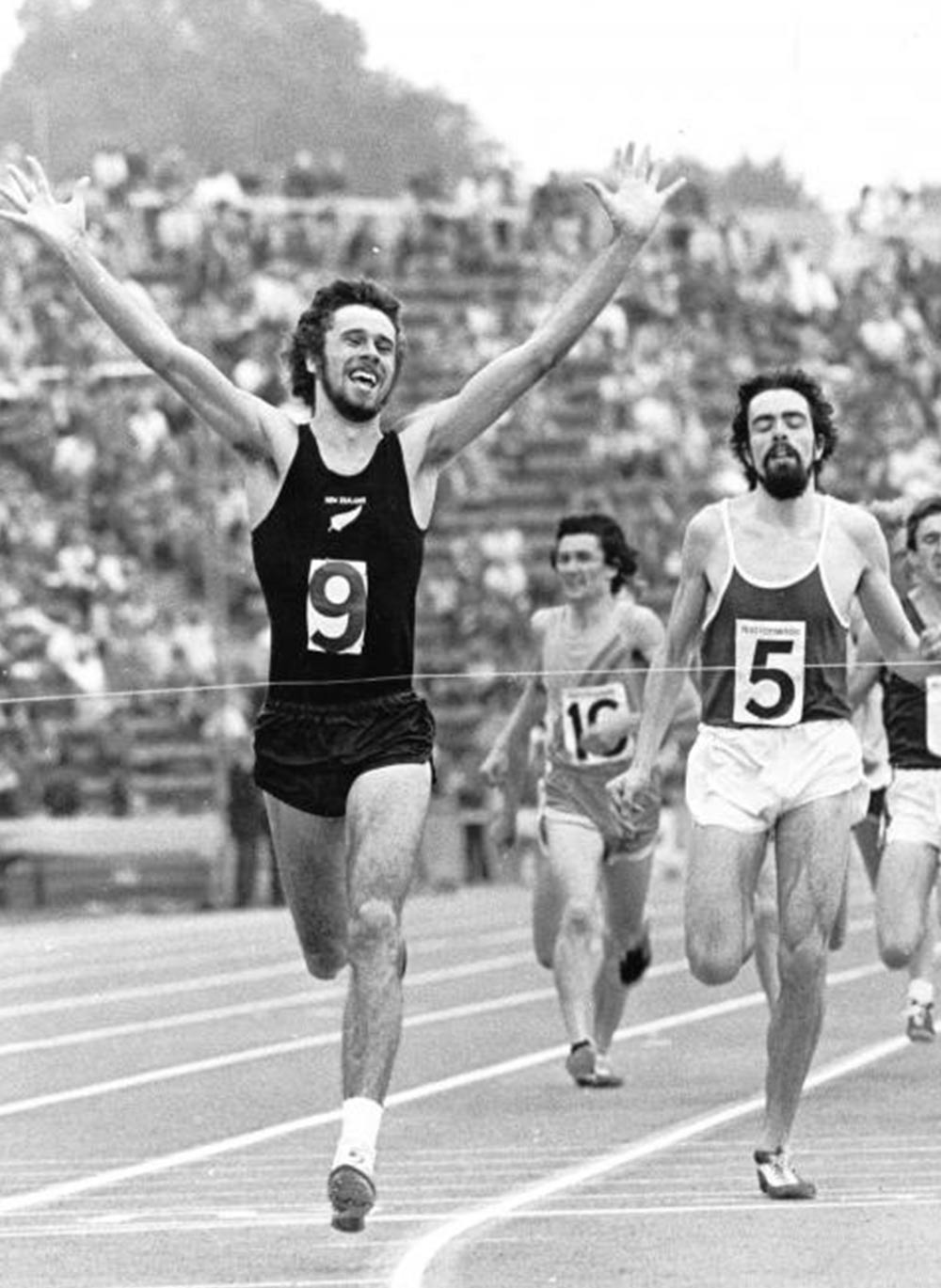

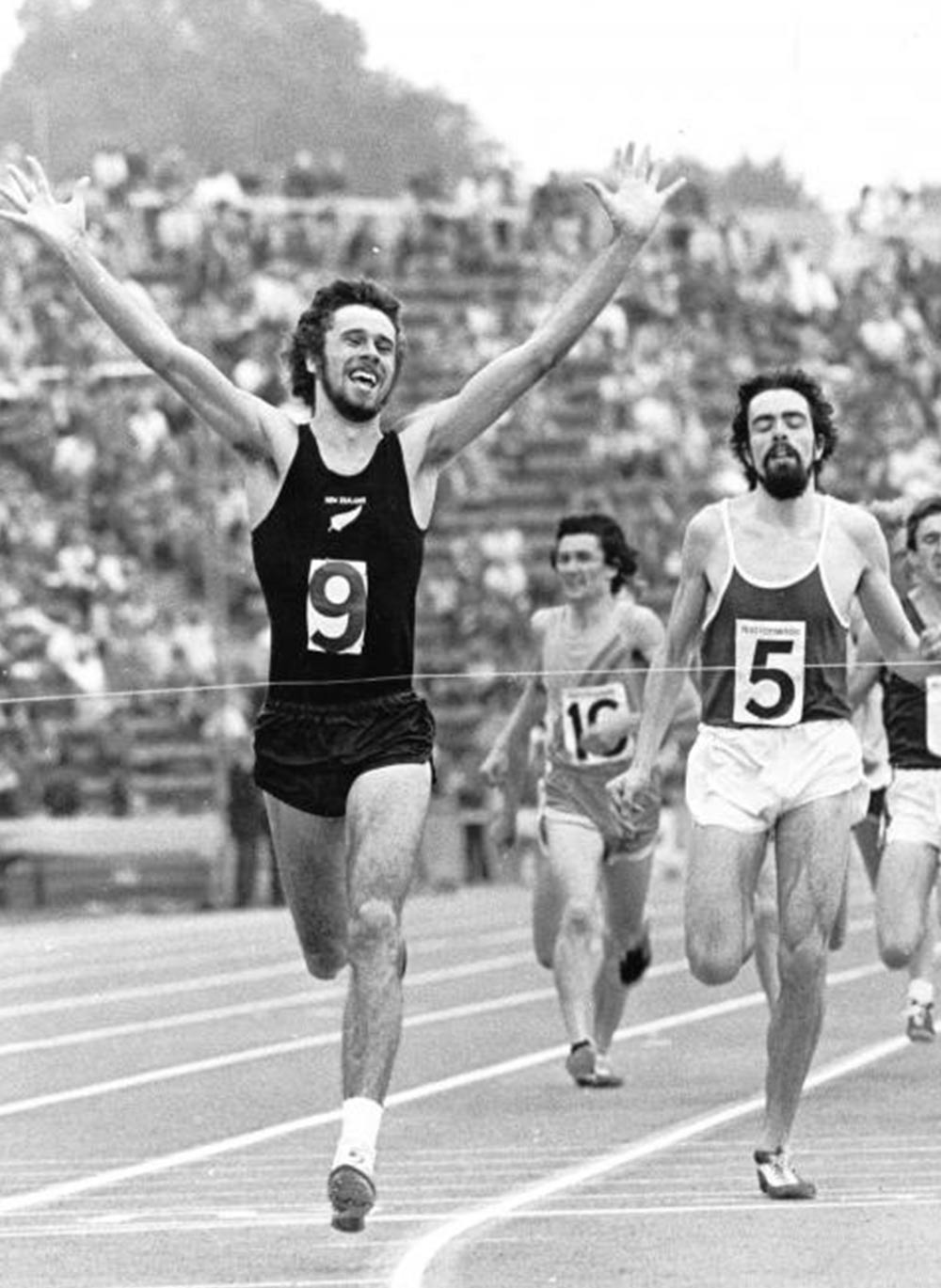

While he didn’t even care about the prizes when he was younger, once he started hitting that line first, he got a taste for winning. Yes, he loved that, too.

Dixon, who will turn 74 just in time for the lighting of the flame for the Games of the XXXIII Olympiad in Paris, won races at a high level over distances from 800m to the marathon, on the track and road and in cross-country. He is widely regarded as the country’s most versatile runner and, arguably, the most talented.

He was also one of the most cursed, although he would never think to put it that way.

When he nestles in to watch New Zealand’s track-and-field contingent in Paris, a talented team that is hopeful of four medals (and, on the flipside, fearful of none), he would be forgiven for thinking of what might have been.

In 1972, nobody expected much out of Dixon except his coach, John Dixon.

“I had a lot of inspirations — Sir Edmund Hillary, our athletics club president Harold Nelson, who won gold and silver at the 1950 Empire Games, Peter Snell, John Davies. But my hero was my brother,” Dixon says. “John told me to believe in myself, that I could achieve things I put my mind to. Whatever John did, I wanted to do it and wanted to be half as good as him.”

John was an excellent, championshiplevel runner, who just missed out on the New Zealand team for the 1971 International Cross Country Championships in San Sebastián. (He would later be part of the 1975 world championship-winning team in Morocco.) Rod made the team and, just 20, finished in the top 10.

“John looked at that and said, ‘We should be thinking about the Olympics, the 5000m.’ I didn’t want to run the 5000m. I wanted to be like Jack Lovelock, Peter Snell and John Davies and run the mile.

“Not many people thought that was a good idea. I hadn’t broken the four-minute mile, I hadn’t been to the nationals, but John thought it was a good idea so that was enough.”

Dixon needed to win the Olympic trials and go under the qualifying time to join national 1500m champion Tony Polhill in Munich. “John paced it for a qualifying time and with 200m to go he moved out of the way, gave me a tap on the bum and said, ‘Move your arse’.” Dixon’s time of 3:41.7 was a fraction of a second under the qualifying time — John’s on-track admonishment turned into a joyous, disbelieving hug in the Mt Smart infield. When, days later, the selectors included Dixon in the team he did the only thing that felt natural to him: he went for a run, barefoot, along Tāhunanui Beach, a grin fixed on his face like it was when he’d deliver Mr Leversedge’s very important notes.

Only the younger Dixon made it to Munich. The New Zealand Amateur Athletics Association — “the only ‘A’ in that title that was accurate was Amateur,” says Dixon — and Olympic Committee were never ones to make life easy for coaches, who they viewed as professionals and, in keeping with the sensibilities of the times, a little distasteful. It’s no exaggeration to say Dixon shocked many by just making the final, especially as the brutal heats accounted for the likes of US star Jim Ryun, the silver medallist from Mexico City in 1968. To then finish third behind Finn Pekka Vasala and legendary Kenyan Kip Keino, while holding off another, Mike Boit, was mind-boggling. Dixon looked every bit as starstruck as the “Dixon in Wonderland” headline suggested.

He, like most of his countrymen, would have assumed it was the first throes of an Olympic love affair, not the start of a long, messy break-up.

It’s hard to imagine now, but there was a time when our best athletes commanded the sort of attention we normally reserved for All Blacks.

While Beamish — who earlier this year surprised by winning the world indoor championships over 1500m — and two-time Olympic medallist Willis went through the US collegiate system to make a mark, the likes of Quax, Dixon and Walker all dominated a thriving local scene before taking their considerable talents to Europe for the New Zealand winter.

One of those annual trips was covered in Kiwis Can Fly.

The very fact a journalist and publisher saw merit in following the fortunes of New Zealand’s best middle-distance runners through the ups and downs of a European season tells you a story in itself.

The book covers the 1975 summer and culminates in Walker shattering the world record for the mile in Gothenburg, Sweden, on August 12.

Dixon smiles at the memory of both.

If Quax, who died of cancer in 2018, was their immediate forerunner and the most self-assured, and Dixon the most versatile and talented, then Walker, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease in 1996, was the strongest.

“The three of us were very close and sometimes very competitive.” There were times they didn’t see eye to eye, sometimes for extended periods, “but our friendship endured and we shared a lot of communication over the years,” he says.

“To me, John Walker was the greatest athlete I ever met,” Dixon says. “I first met him at the Olympic trials in 72. Bruce Hunter, the All Black wing, beat him in the 800m after John had a good season and the selectors didn’t pick either of them for Munich. I remember watching John run on grass at Tauranga and thinking to myself, ‘This kid is really good.