BLUFF

Great, white and very inquisitive

An encounter with a surprisingly gentle giant.

“Do not attempt to touch the shark.” You might think that it goes without saying — especially this summer, when coverage of attacks, encounters and even sightings has been at fever pitch. But after nearly 15 years of taking people cage-diving with great whites, Mike Haines knows better.

The message is repeated during the early-morning arrival at the Shark Experience office, harbourside in Bluff; in the first briefing onboard the Southern Isle as it charges into Foveaux Strait; and on signs everywhere you look that read: “Keep all body parts inside the cage.”

Most people get it, says Haines. “I’ve had one idiot. He stuck his head out, with his camera.” Haines hauled him out of the water, where he was less of a danger.

Some level of risk is inevitable when it comes to bringing together people and apex predators. Great whites are avoided even by other sharks. They can be 1.5 metres long at birth; fully-grown females often exceed 6 metres and weigh more than two tonnes.

The most great whites Haines has ever had circling the cage at one time is nine — very nearly two for every person inside. Yet the first challenge of setting up his business, he says, was figuring out how “not to hurt the shark”.

Born in Invercargill, Haines has been diving in New Zealand’s southernmost coastal waters since he was a teenager. A couple of times, when he was collecting crayfish, a great white emerged out of the blue, wanting its share. “It’s not a sight you want to see if you’re diving,” he says.

But they were just inquisitive, he says. “It’s the one you don’t see, that’s the issue.”

Haines was running his own dive shop in Invercargill when, in 2007, a documentary production company approached him about filming great whites around Stewart Island. Compared to those in South Africa and South Australia, they were a little-documented population.

Yet out on the water with the film crew, the sharks showed day after day, for weeks — and Haines saw a business opportunity.

To attract the sharks, Haines has experimented with heavy metal music and seal silhouettes cut out from carpet.

The learning curve was steep, informed by international best practice and shaped over the years by an increasingly restrictive regulatory environment. As one of only two cage-diving operators in New Zealand, Haines’s business has been the subject of a long-running legal battle. Stewart Island paua gatherers and swimmers argued that cage diving alters the animals’ behaviour, making them more aggressive. Subsequent research found no conclusive evidence for this, and in late 2019 the Supreme Court sided with Haines against an earlier decision that had ruled cage diving an offence under the Wildlife Act 1953. At least for now, he is able to take out groups of about 10 people most days from December to June.

Our destination is Motunui, one of the Titi (or Muttonbird) islands north-east of Stewart Island, where there is a resident seal colony, a key draw for great whites. Even more enticing is the potent mix of fish blood and guts known as berley that Haines releases into the water via the holding tank — creating a trail that leads to the boat.

The advantage of this approach is that “it’s clean”. “You don’t end up with a big mess.” The smell, unfortunately, is unavoidable. The use of any attractant is the subject of heavy external scrutiny: berley is permissible in that it gives the shark no tangible reward. In the past, Haines and his two-person crew have experimented with heavy metal music and seal silhouettes cut out from carpet (that last one being a bridge too far for the Department of Conservation).

Shark Experience makes customers no guarantee, but says that in the “rare event” no sharks are sighted, they will be offered a voucher for a return trip within the coming year. Today, Haines, his gaze trained off the back of the boat, sounds the triumphant alarm within a half-hour of dropping anchor.

“Shark! In front of the cage. Maaarvellous.” The first-time divers had only just descended inside, to get comfortable with breathing underwater.

It is a juvenile female, about 3.3 metres long with distinctive white markings across one eye. Ever since Haines first encountered her a few weeks ago, she has been a repeat visitor. “She likes us, you see.”

Initially, she keeps her distance, fairly deep beneath the surface. Watching from the boat, there is no telltale fin — only a passing shadow, sometimes a glimpse of white. You could easily not see it, even if you were looking.

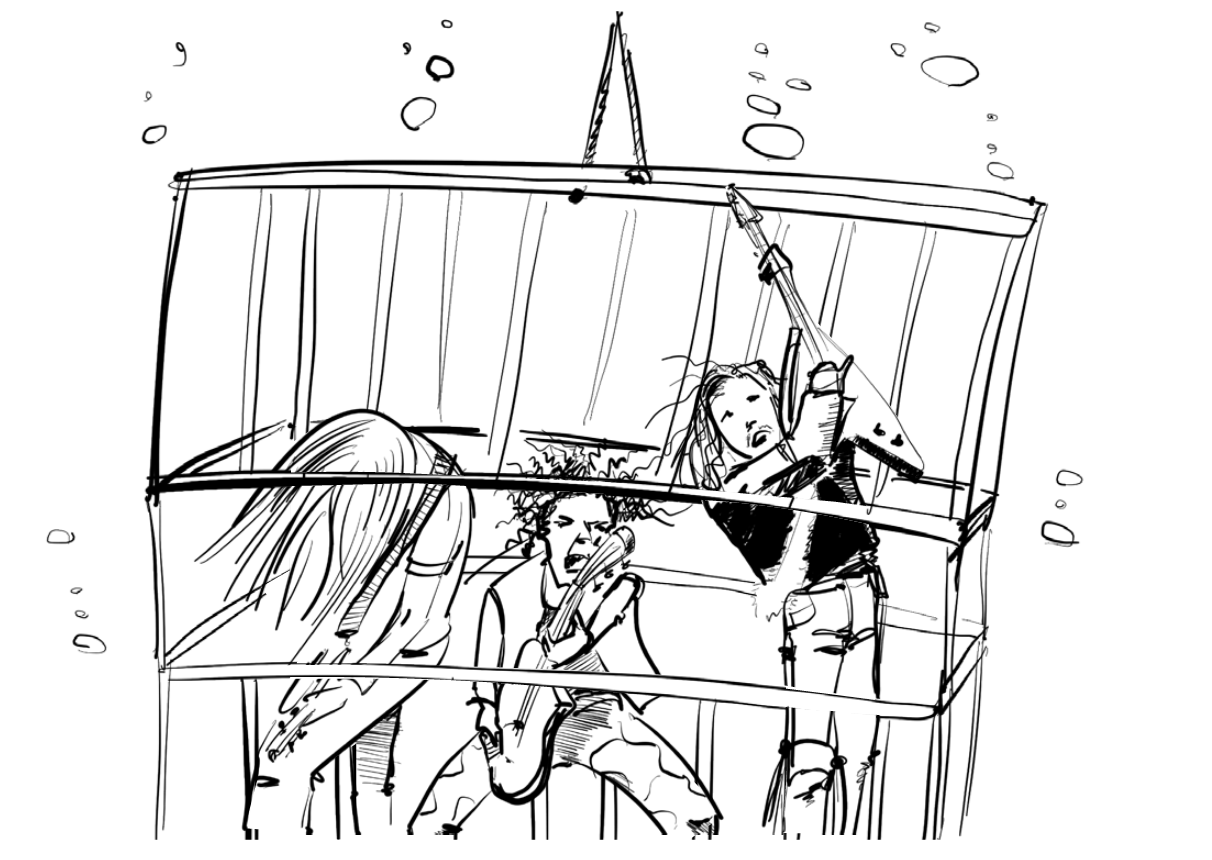

Illustration: Imogen Greenfield

“They’re all different,” says Haines. “Some are very standoffish, some are shy. Some have attitudes, some are cruisy, casual . . . You’ve got to allow them to do their thing.”

Dragging a hooked tuna head off the back of the boat to lure the shark closer is allowed, so long as she doesn’t get to bite it. But part of what keeps her circling the cage, for hours, is her curiosity about the divers inside. From that vantage point, she does not loom out of the darkness; she just appears.

The suddenness of it seems almost implausible considering both the shark’s girth, and its relaxed, slow-moving state. It bears little resemblance to the depictions of great whites in popular media, even documentaries, as teeth-baring, gurning monsters. “A lot of the occasions that you see them on TV, keep in mind that they are provoked to do that for the camera,” says Haines.

Pour enough berley into the water, and “yes, you would probably turn them into a vicious animal”. But the one we see before us seems inquisitive but not (at least at the moment) especially predatory. The absence of fear inside the cage is striking. Of course, we are a self-selected sample. But Haines says there are also people who sign up for cage diving to solve their phobia of sharks, and today’s experience just goes to show how that might be effective.

There is, inevitably, a bit of an adrenaline rush. But the key takeaway, many of us agree, is how different the animal we see before us is to the one we thought we knew. “At the end of the day, it is more about education,” says Haines.

Great whites have been protected in New Zealand waters since 2007. The aim is to help save a species in global decline and to support the health of ocean ecosystems. A recent study found that the global number of oceanic sharks and rays has declined by 70 per cent since 1970 and that those that endure face threats on several fronts.

Research published in February found that warming sea temperatures were pushing great whites into new waters, with a “dramatic increase” in juveniles recorded off California. In South Africa, numbers have mysteriously depleted to such an extent that cage-dive operations have gone out of business, possibly as a result of increased predation by orca.

The chief threat to Haines’ business is Covid-19, halting international tourism. Cage diving with sharks is a popular bucket-list item, and a great draw to Bluff, he says. “Our numbers have been less than a third of what they normally would be.”

He does not believe the Stewart Island sharks’ numbers or behaviour has changed over the decades that he has been diving and working with them. But what remains a constant, Haines says, is how little we know about them.

Even basic information about their migratory patterns, where they go when they leave Foveaux Strait, is a mystery — hindering efforts to save the species. Recently, Haines says, he saw a 15-year-old shark that apparently had never been documented before. It may be the promise of danger that brings people to his boat. But when they depart, Haines asks them for any photos that might help to expand understanding of the species. Those of tails, dorsal fins and identifying marks are especially useful. And, he tells them: “We’re not interested in teeth.”

Elle Hunt is a freelance writer based in London and Wellington. She writes mostly for the Guardian, where she was a reporter and editor for five years. She recently returned to New Zealand and is still adjusting to the freedom of a (mostly) Covid-free society.

This story appeared in the May 2021 issue of North & South.