The family album

Interdisciplinary artist Stella Brennan remixes archival objects into anti-nostalgic meditations on progress and history. Thread Between Darkness & Light is Brennan’s most personal artwork, and one of her most beautiful.

By Theo Macdonald

“How can we know what (or who) we do not know?” This lofty challenge begins The Aotearoa Digital Arts Reader, artist Stella Brennan and writer Susan Ballard’s prescient 2008 anthology on digital artmaking. Fleshed out a bit, we could translate Brennan and Ballard’s question to mean, “How can an artwork create opportunities for its audience to reconcile unreconcilable gaps of knowledge and experience?” Sixteen years on, knowing not knowing remains an instigating challenge throughout Brennan’s eclectic cross-disciplinary output.

Her 2007 video South Pacific asked how an early process of ultrasound technology might explore the time-space compressions of World War Two. 2018’s Object Permanence probed current-day techno-optimism by filming a sweep of land in Kaipara Harbour once mooted as the site for New Zealand’s first nuclear power plant. And Thread Between Darkness & Light, Brennan’s new photo book published through Rim Books, exhumes her great-great-aunt Louise Laurent’s collection of century-old glass plate photographs to confront the impossibility of truly understanding the long-dead ancestors to whom we owe our present-day existence.

Brennan’s home studio is a churchy space bunkered in the Te Henga bush. The sturdy structure mirrors Brennan’s matter-of-fact artmaking. Seemingly without self-doubt or uncertainty, her projects are robust alloys of historical research and material experimentation. On jammed bookshelves, texts like IBM and the Holocaust, and a catalogue on German artist Hans Haacke, foreground Brennan’s interests in industrialism, tech, histories of violence and the limit of representation.

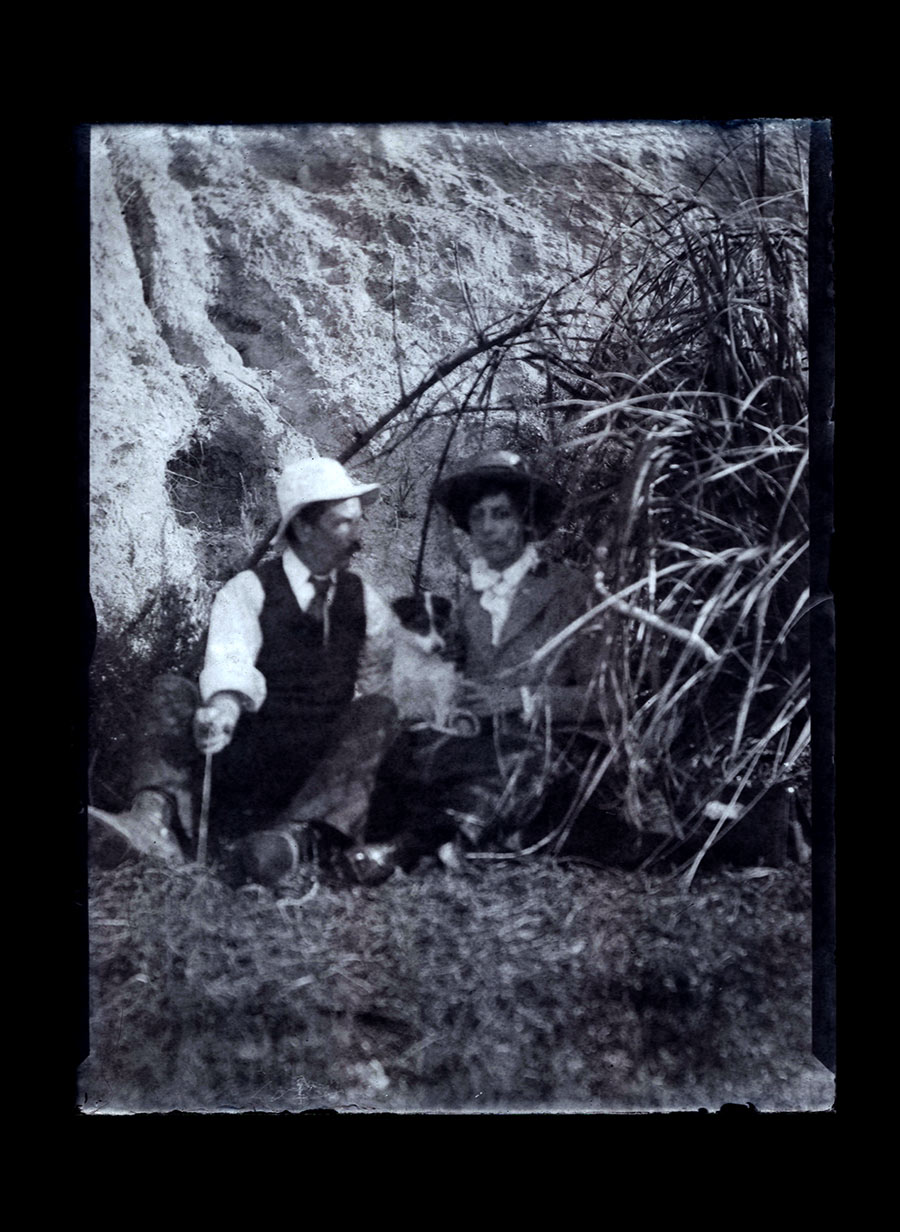

The studio’s wooden walls catch the soft morning light; Brennan tells me this interview was the much-needed catalyst for a proper cleanup. On one wall hangs a large silk print. In the image, a man and woman, Laurent and her husband William Winn, sit on scraggy grass beside an unruly clump of flax. Winn, in a waistcoat and sun hat, has his head turned to Laurent, who stares down the camera. Both are out of focus, meaning you could easily miss the terrier perched between them. The glass edges of this spectral family portrait are chipped and serrated like the teeth of a great white shark. A blossom of mould advances north.

It wasn’t until Brennan had been living with this print hung on her studio wall for weeks that she realised it was a selfie. The out-of-focus man is pulling an out-of-focus cable to set off their camera’s shutter.

Standing at a long desk opposite, Brennan opens a grey archival box and removes one by one, from cotton-y tissue paper, a series of gelatine bromide dry-plate negatives. Each one is the size of a Pop-Tart and was made more than fifty years before Pop-Tarts were invented. Brennan handles these fragile, often cracked family heirlooms with the delicate familiarity of a chef dividing albumen from yolk.

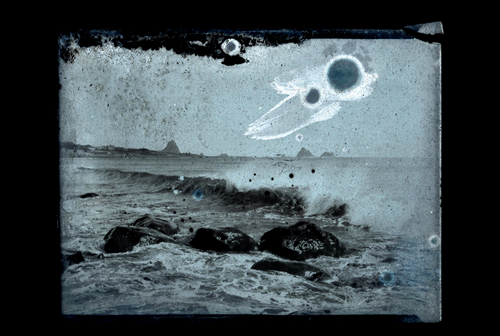

In Thread Between Darkness & Light, images of spectral landscapes and phantom children are rendered in abyssal blacks, tropical indigos, arctic whites and hydrangea blues. On the glass negatives, on the other hand, the photographs are faint, ghostly white.

Brennan scanned each glass plate on a consumer scanner — she compares seeing each scan materialise on her computer screen to the darkroom magic of watching a latent photographic image emerge on light-sensitive paper — and hasn’t attempted to “restore” the images by digitally painting over cracks in the glass, scratches in the emulsion, or big beautiful blurs of mould.

Why? Because these marks of time denote Brennan’s bridging of the known present and the unknowable past; because it is in the interaction between glass and fungus that Aotearoa’s whenua becomes visible; because deteriorated, decomposed photographs, in the words of artist Hito Steyerl, “testify to the violent dislocation, transferrals, and displacement of images.” By overtly emphasising the decay of these objects, Brennan impugns the authority granted to high-resolution imagery in our visual culture.

The survival of Laurent’s fragile glass plates to the present day is a miracle. Today, cameras are embedded in everything from phones to fridges, with photographic data produced by consumers at an incomprehensible rate. But just because we are generating these files does not mean they will exist even twenty years from now. Digital information is vulnerable to hardware obsolescence and corporate dissolution. In 2019, in a botched server migration, Myspace lost all the music uploaded to its service before 2015 — some 50 million songs.

That the object Brennan works from could survive until today, bearing their scars as evidence of a century, is a destiny our digital photographs simply do not have. The thousands of happy snaps on our phones and laptops will all vanish in one data loss or another.

But Thread Between Darkness & Light didn’t begin with photography, digital or analogue. The project began with a painting on the wall of Brennan’s uncle’s house, a gold-hued landscape with Waitematā Harbour and Rangitoto in the background, and an ivy-covered church in front.

Brennan’s elderly uncle told her he believed his aunt, Louise Laurent, was responsible for the painting. Brennan Googled the unfamiliar name and found an 1897 class photo from Elam School of Arts, the same institution Brennan attended nearly one hundred years later. Intrigued, she went through her late father Mervyn’s papers and uncovered a distant cousin, Maurice Winn, who she met and who gave her a stack of glass plate negatives he had found under bags of fertiliser and kept when his grandmother passed away in the 1960s.

The 300 glass plates, stored inside Blue PVC folders, portrayed, in Brennan’s words, “dogs, boats, kids, gardens, sunsets” — namely, the material of all amateur photography. More than that, however, these indiscriminately preserved negatives depicted tantalising subjects far more abstract: family, friendship, fashion and modernity.

We are obliged to know how we came to be here, Brennan tells me. Pākehā should know the pathways that brought their ancestors to this land, lest they/we presume their/our place here is an entitlement rather than a privilege.

At first, Brennan felt “like an imposter” working with these relics of her distant relatives. It was a familiar feeling. In 2007, she had made an artwork, White Wall / Black Hole, using scant archival film shot aboard Air New Zealand Flight 901 shortly before it crashed into Mount Erebus. The extreme sensitivity of this project permanently altered her attitude toward “appropriate” use of archival materials. She showed White Wall / Black Hole to the chair of the Airline Pilots Association, a representative of the Erebus families, who asked tough questions before ultimately coming to agree that her work was sufficiently respectful.

Reviewing Louise Laurent’s glass plates, Brennan felt uneasy about interpreting these images of unknown relatives. Then, early in the scanning process, she found a portrait of her grandmother Doris with Doris’ adopted mother Adele, the older sister of Louise Laurent. Pieces of her messy family history began falling into place. That she only came into possession of these family heirlooms recently, Brennan credits to a schism in her family, tied to the insolvency of her grandfather, a carpenter. In the national archive, she read his testimony to bankruptcy court. He wrote, “I am left with only my tools.”

In the past, I have been challenged by how Stella Brennan seems to halt each project one step short of an answer. Curator Robert Leonard calls her refusal of resolution “ambivalence”. Media theorist Sean Cubitt prefers the term “numb”.

In Brennan’s 2006 Walters Prize-nominated artwork Wet Social Sculpture, Brennan layers humpback whale song, abstract footage appropriated from 80s horror film Altered States, and a functioning spa pool attendees were encouraged to enter. The project chewed over themes of suburban psychedelia and heterotopia (crudely put, actual spaces which reflect, counter and model the larger society they are within, such as prisons or swimming pools). Curator Natasha Conland wrote of the work, “You might ask to what extent is utopia now achievable”, a question for which Brennan’s reply — Wet Social Sculpture — is complex and ambiguous.

Of course, artists are not supposed to correct society’s ills with taglines or policy documents. Marshall McLuhan believed the arts act as “an early alarm system”, enabling society to anticipate future crises and learn to cope with them. Brennan’s Digital Arts Reader anticipated the demise of print culture. Thread Between Darkness & Light reintroduces material photography to a future that will have very little.

This not-knowing is Brennan’s practice’s most enduring quality. She turns over political realities, like nuclear power and colonial expansion, without reaching easy conclusions. It allows each project to remain generative after she has moved on. Thread Between Darkness & Light does not claim Louise Laurent and William Winn are the missing authors of our national history. Brennan does not promise that these photographs can confer total (or any) insight into the lives of the long-dead. And because we don’t need to hold our breath while sliding between epiphanies, we can look at these images as what they are: the photochemically fixed surfaces of objects that testify to the continued residue of experiences we cannot possibly know.

Thread Between Darkness & Light is available from rimbooks.com