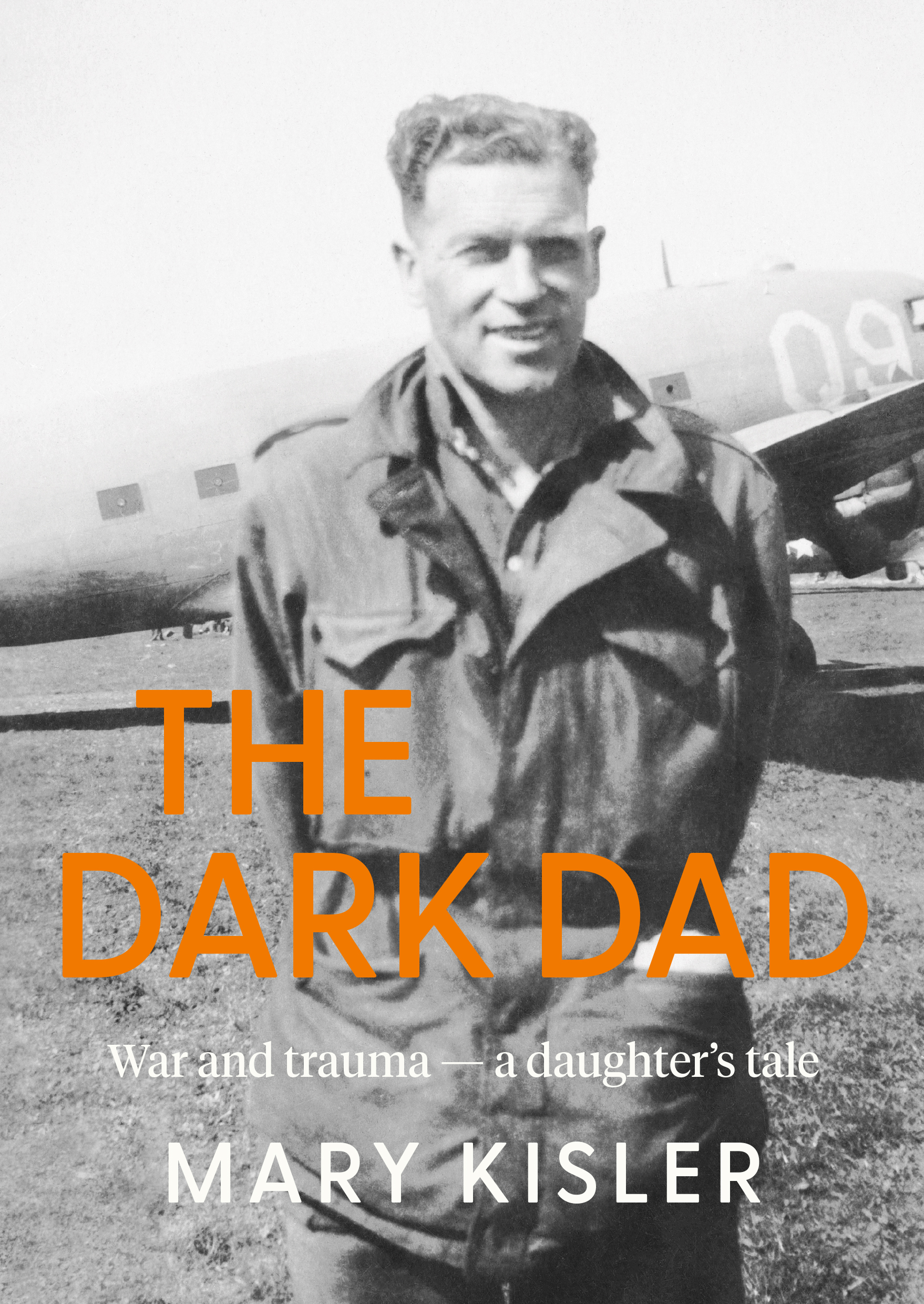

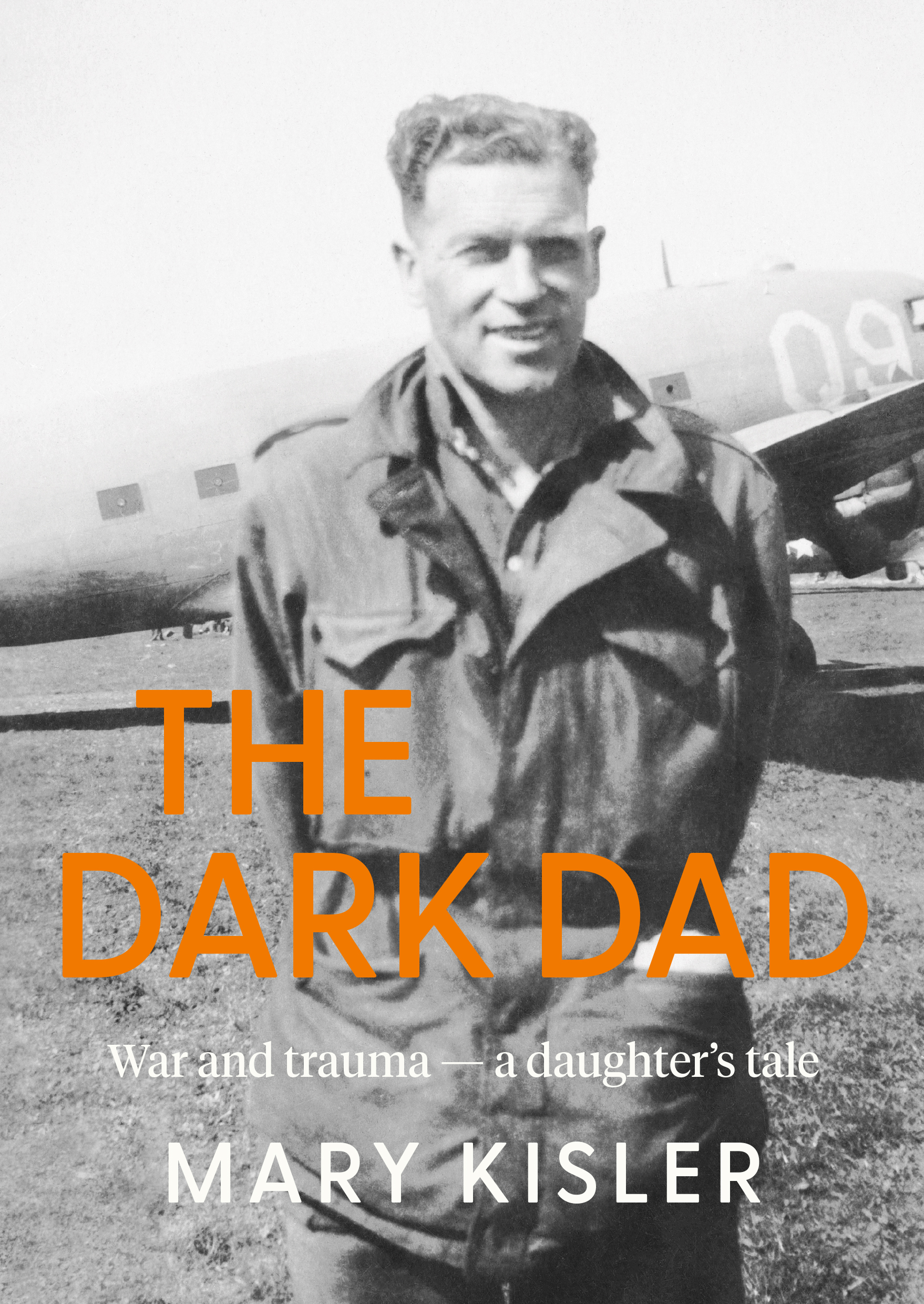

The Dark Dad

10th April 2025

Mary Kisler’s memoir about her father, who was taken POW in Italy during the Second World War and returned home with PTSD, is a powerful, redemptive story and also one of forgiveness. An edited extract recalls the profound consequences of war for the family, and for the man who left with one personality and returned with another.

I stand at the doorway, fists clenched, gazing up at the little painting that hangs on the narrow strip of wall above the telephone table. The young woman seems to be glancing in my direction, her hair covered by a blue and yellow turban, its fringed ends cascading down her back. I wonder if her hair is light or dark and I wish that she would unwrap the cloth for me to see. Her face is gentle, the large pearl earring shining so softly that I almost forget my fear. I want to reach up and touch the pearl, but know I will only touch the smooth, cool glass that protects her.

The dark frame of the doorway seems to close in on me as I turn to stare at the space beneath my narrow bed in the far corner. I take a deep breath, close my eyes tightly for a moment, and then run, leaping, sinking onto the complaining springs, rolling the bedding over my head. Slowly my breath calms. Quieter than a mouse, I peel back the sheet. The house is silent, apart from my younger brother’s soft breath in the other bed, and in the dim light from the hall I can just make out the pale-blue stripes of his flannel pyjamas.

Raindrops trace their way down the window, illuminated by the street lamp beyond the front garden. My eyes grow heavier, and sleep wraps me softly in its arms.

Not every bedtime ends so well. Some nights I slide beneath the covers and weave my fingers through the wire-wove base under the mattress, the metal sharp against my skin. I have a choice — to hang on or to push my fingers into my ears. The sound of my brother’s tight breaths tells me that he, too, is listening. Will the ugly noises we hear through the wall come closer, or will they soften and cease?

At the sudden sound of running, I roll quickly across the mattress, my face pressed into the narrow gap where the bed meets the wall, waiting for my mother to leap in beside me and hold me tight. I can sense the dark dad standing in the doorway. In my mind, he roars like a bull, but my mother knows he will not come closer while her children are there to protect her. As her panting subsides, we nestle closer, and after some time we all slip into a wary sleep.

Only once does the dark dad cross the threshold, and in an instant we are out the narrow window, leaving the metal hasp dangling.

Mum has always been fleet, and we follow her like baby ducks in a line. Other times we leave by the front door. My older brother sleeps in the sunporch and must slip out the back and up the narrow path beside the house. What does he sense when my mother leaps into my bed? He must lie awake, too, listening for the slightest movement, but who will protect him if he is in the porch on his own?

Somehow or other, we find ourselves outside in the dark, our mother guiding us swiftly down the hill and across the road. Steep driveways lead down to a lower footpath, and we make our way to a low stone wall, a dense hedge rearing up to one side. Huddled together, we wait until dawn, when the dark dad leaves the house.

After we hear the truck driving away over the hill, Mum shepherds us home and back into bed. None of us will go to school that day, and Mum will write a note to our teachers saying we have all come down with a stomach bug or something similar.

Once, when Dad has pushed a lighted cigarette into the corner of Mum’s eye, we climb over the low fence to our neighbours’ house, and they tuck us into bed. We can hear Mum talking softly in their sitting room. Our neighbours are English, and even as a young child I recognise that their comfortable lives are very different from ours.

Another time, when we are a bit older, a car comes and we are whisked away to my uncle’s house in Remuera, where we lie in other people’s beds, exhausted by the evening’s events. I sense my uncle doesn’t approve, and that somehow it is my mother’s fault that things aren’t ordered in our household.

One night, as Mum races into our bedroom, my younger brother starts to scream, a high-pitched wailing, on and on, as if the stripes on his pyjamas have risen up to slither through the air like silver blue snakes. Sometimes at night I can’t get the sound of Mike’s distress out of my mind, and I am frightened that I, too, might start wailing, unable to stop, until the room fills with snakes and I can no longer breathe.

Aftermath

On 7 July 1945, the personal column of the Otago Daily Times referred to my father’s return to Otago:

Gunner Jack Arnott, of Palmerston, who returned to his home recently after being a prisoner-of-war in Germany for three and a half years, has been visiting Milton this week in company with his mother, Mrs W. Arnott. Gunner Arnott was a popular member of the Toko Football Club while resident in Milton, and he expressed thanks to the secretary of the club (Mr H. Wilkinson) for the club’s generous donation towards a parcel . . .

If Dad had a tūrangawaewae, Milton was it. However, after a brief spell with his family, he returned to Auckland and re-established contact with my mother. This suggests they had remained in touch, although she never mentioned writing to him while he was away. My instinct is that he would have sought her out, and she would have been glad he did. Jack Arnott seemed to offer a chance of happiness and the family she had always longed for.

When I asked my mother years later why she had married Dad, she answered, ‘Because he could fix things’. It brought to mind the story she told about how she and Dad went on an outing to Auckland’s west coast beaches with family and friends, and the vehicle they were travelling in broke down. While the other men in the party threw their hands in the air, my father set to and fixed the engine so that they could resume their journey.

During their two-month engagement they were photographed at 27 Landscape Road, sitting together in the sun. Glued to Dad’s side, my mother is holding a large tabby cat, which rests its head on Dad’s arm, while he in turn holds its paw. They were married at St Barnabas Anglican Church in Mount Eden on 29 September 1945. The wedding was simple, but despite ongoing restrictions on fabric, my mother wore a snappy tailored suit with a scalloped front, and a rakish hat with a rose in a style that was the rage at the time, and which may have been provided by her sister.

Shortly afterwards, my parents moved to Dunedin. My father longed to be nearer his mother, in a community where he was known, and where he had earned respect before the war. They moved into a small flat in York Place, up from the Octagon, but it wasn’t long before Ethelwyn found Dunedin difficult — she was lonely, knew no one, and apparently their landlady was a terror. Worse, there were already signs that her marriage was not going to be easy.

Like so many returned POWs, Dad had recurring nightmares, and she would wake at night to find him gone, striding the streets of Dunedin in the dark, unable to cope with being confined. She conceived almost immediately, in spite of earlier warnings from doctors that she might be unable to have children, and she finally persuaded my father that they should return to Auckland where she would have the support of her family. They moved back to live with Win at 27 Landscape Road.

My brother John was born on 11 August 1946. His birth was very difficult, for my mother was tiny, and she was bedridden for three months. Dad briefly hired a nurse to look after her until Win generously agreed to leave the army in September to take on the role of carer — a duty still expected of unmarried women at the time. A year later my parents bought number 37, the bungalow in which my great-grandmother had lived, three doors down the hill, taking on a mortgage that was paid out only 10 years before my father’s retirement.

No doubt my mother took comfort that many of the neighbours she had known from childhood were still living nearby, some in the elegant and very substantial houses that sat atop the hill, and number 37 and its large garden, although not her childhood home, were full of family memories. The two-bedroom bungalow was small, and my mother later claimed that it was saved from falling down because the borer were holding hands.

On 16 August 1947, two months before I was born, my father was permanently discharged from the army (NZ822 Certificate of Discharge 39503). I arrived the day they moved into number 37, and when my mother said she needed to get to the hospital, my father, thinking she was fussing, asked her to wait until he had finished hanging the curtains. It was Labour Day; they got caught up in race-day traffic, and only just made it in time. At birth I weighed 4 pounds 10 ounces (under 2 kilograms); when they took me home, Dad put me in a shoe box to see if I would fit.

***

I could have been no more than five or six years old when my father borrowed money from one of my mother’s aunts to buy the lease on a quarry at Whatawhata, outside Hamilton, on the banks of the Waipā River. Like many other ex-POWs, he was happiest when he was on his own, and he would spend the next few years there, apart from brief visits home. I remember visiting there once, more excited about a baby lamb he had borrowed from a neighbouring farmer for me to play with than paying attention to the tiny hut in which he lived. It was fairly primitive, by all accounts (I remember only a dark, unpainted wooden interior), but it was his to do with as he pleased.

In 1954, after a flood, he was forced to abandon the quarry and return to Auckland. He was never able to repay my great-aunt, who accepted that the debt would have to be cancelled. Her own husband had been badly injured before being captured in the First World War, and perhaps she had some insight into the troubled mind of an ex-POW.

Two of Mum’s siblings owned baches at Murrays Bay on Auckland’s North Shore, where they spent their summer holidays. They knew the area well because the family had had a hut by the stream on Mairangi Bay until the Labour government confiscated it for the homeless after the war. Wanting to give us seaside summer holidays in the company of our cousins, most years my mother managed to save enough money for us to rent accommodation of our own.

The first I remember was a primitive little bach that she rented one year when I was about five. It had the advantage of being next to the substantial fibrolite bach built by her younger brother Howard when he came back from the war, and we were in awe of its large sitting room and modern cane furniture with coloured bands of green and red, as well as of its large windows looking out over the sea, so different from the dark stained wood and somewhat gloomy interior of Landscape Road.

That year, my father travelled up from Whatawhata, arriving at the bach late on Christmas Eve, long after my mother had tucked us into bed. He had been given a bottle of whisky as a Christmas present — a gift we all came to fear — and the inevitable row ensued. On Christmas morning I discovered that my presents had been damaged. Dad had wrenched the blonde wig off a little doll my mother had saved up to buy, and a miniature tin cooking set had been crushed. Mum said he only did it to hurt her, but I was heartbroken.

Yet there were also many happy times at Murrays Bay. We roamed the local beaches, and in a photograph showing a mob of cousins and parents sitting on the sand Dad is in the front row beside me, his hand resting on my ankle. That was the year Dad encouraged me to jump with him off the long wooden wharf that stretched out into the bay. He hadn’t considered our different body weights, and I was dragged down deeper and deeper, my hand clutched firmly by his, struggling to hold my breath.

Dark Dad: War and Trauma – a Daughter’s Tale. By Mary Kisler. Published by Massey University Press, $37. Available April 10.