How new AI soured my love for tech

5th June 2025

Ben Moore has always loved technology, the way it pushed boundaries. But AI is a bad actor, he writes, and the game has changed.

By Ben Moore

An unhealthy number of my core memories involve computers.

Christmas in the 90s; my dad calls my name 100 times and laughs at how absorbed I am in Donkey Kong Land 2 on my shiny new Game Boy.

Home sick with a cold; I’m sitting at the PC in the garage wrapped in a heavy blanket, my hands ice-cold on the keyboard and mouse.

Lunch time in the computer lab; a small group of us create Geocities websites trying to collect more Dragon Ball Z pixel sprite gifs than each other.

Pictures that move!?

My point is: I always loved technology.

An older millennial, I missed the birth of the internet but I grew up alongside it and watched it transform from a refuge for freaks and geeks into the very foundation of everything we do.

While cloud computing got its start in the mid-2000s, it was around the 2010s when we hit the accelerator hard and unintended consequences started falling out the boot.

Cloud data centres exploded in size and became power and water hungry beasts.

Email grew into instant messaging then into social media. Advertising moved in and the benefits of mining personal data for targeted ads was discovered, which soon begat trackers following your every move across the internet.

Apps brought us incredible convenience of service, but also exploitative gaming, price-gouging, subscription overload, and the “own nothing and be happy” mindset.

With all of those examples, it felt the same as fossil fuels or plastic: we found something incredible and pushed the boundaries to see what we could do, but didn’t see the negative side effects until it was too late.

While exploitation and greed made things worse, they were jumping onto established tech that was doing amazing things. As we saw the damage being done, social movements grew to try and combat them and businesses started talking a big game about being better.

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand in particular, with the Lord of the Rings at our backs, we sailed forth on the pillars of greenness and creativity (and rugby, I guess) and wrapped a good chunk of our national identity around pushing back on corruption, greed and exploitation.

While some places gave into smog and rubbish-laden waterways, rote learning and teaching to the test, lobbying and pseudo-bribery – we watched on, shaking our heads in quiet disapproval.

We were far from perfect but we wanted to be good.

While we had made a lot of mistakes in our pursuit of better tech, it seemed like we were at the head of a global movement trying to fix them. Slowly, incrementally, but always trying.

I felt deeply that when the next great tech came around, we would know how to think cleaner and kinder about advancement.

And then OpenAI launched ChatGPT and the rose tint turned red.

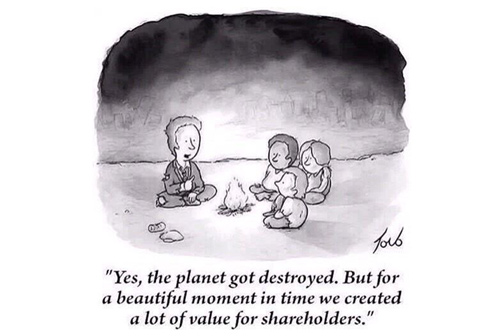

Generative artificial intelligence (AI that can generate text and imagery) and large language models (AI that is trained on extreme amounts of human language) were hurled into the world and I watched in horror as we arrogantly strode right into all those consequences as though we’d learned nothing.

And look: I do think LLMs are impressive have some really good and interesting applications. I also don’t think anyone who uses LLMs is morally wrong (see: The Good Place problem), although I do think there are morally wrong ways to use it.

My problem is not with the tech, but with the system that surrounds it.

I’ve realised that the negative consequences I thought were mistakes we were learning from were actually parts of a machine that has become finely tuned to make money and fuck everything up.

LLMs did more to wash away any big business veneer of empathy than anything I’ve seen in my lifetime.

In a recent article covering some telco-sponsored research about AI, the head of that telco is quoted saying both:

- these tools were “one of the single greatest opportunities” for fixing climate instability, and

- not to say thanks to an LLM because that will use a litre of water.

As a wise person once said to me: “you can’t consume your way out of a consumption problem.” In other words, a product contributing to a problem probably won’t be the solution to that problem.

To be clear, it’s not that it couldn’t be because it doesn’t have to be so terrible.

AI companies could focus on efficiency over speed, commit to only using renewable-powered data centres, offer the latest models to climate academics for free, direct efforts at training and tuning for solving these problems, stop saying “move fast and break things” every five seconds, and if they did those things maybe I would have some small faith that it could happen.

But they won’t.

They’ll keep on burning everything in their path in the pursuit of profit, wearing a cloak of false beneficence to dazzle all but the most ardent critics.

And speaking of false cloaks, let’s talk about the incredible marketing behind these technologies.

In the early 20th century, Edward Bernays mastered the art of twisting negative press to become a positive, downplaying the studies showing the distinct harms that tobacco caused and convincing women it would make them skinny feminists.

Nearly 100 years later, Bernays’ methods are now ingrained in marketing practice but perhaps the most masterful use I’ve seen in recent times was when OpenAI founder Sam Altman claimed he was making artificial intelligence that might destroy the world.

To be clear, based on my understanding of the technology’s limitations and strengths, I am certain that LLMs alone will never be able to replicate human intelligence – they may form the language layer on top of another technology, but they are not capable of becoming the core of any so-called “artificial general intelligence” or “super intelligence”.

On top of that, I don’t see why a super intelligence would just kill everyone. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: it seems just as likely it would force us all to go vegan.

But saying it will destroy the universe is really good marketing.

To quote a piece by US tech journalist Brian Merchant: “Scaring off customers isn’t a concern when what you’re selling is the fearsome power that your service promises.”

Bernays aligned smoking cigarettes with feminine ideals and a century later rich tech CEOs are aligning their glitchy language-based automation tools with dystopian sci-fi.

But it doesn’t stop there.

Creepy, flirty celebrity sound-alikes, soulless impersonations of the most soulful animation studio in the world, the constant assertions it will cure the loneliness pandemic, these tech companies will see any hint of interest and throw hype-gasoline on it without a single care for any kind of ramifications.

And then there’s the wholesale ingestion and regurgitation of intellectual property, from fine arts to journalism to whole novels.

Even one of our most precious cultural touchstones isn’t safe:

From Google’s Gemini with the prompt: “Give me an image of Gollum as close to the version from Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings as possible.” It cost me nothing and wasn’t even hard.

Not only did AI vendors not bother to ask for permission to take people’s work, but when anyone asks for an apology they raise a metaphorical middle finger.

Unless it’s their intellectual property of course, because they’re the saviours who must be protected at all costs, and while I’m being facetious it’s pretty blatant that those CEOs see themselves and their companies that way.

It’s a “for the greater good” attitude that wizard Nazis used as a slogan in the Harry Potter books, and if even noted bigot J K Rowling considers it a poor justification for bad behaviour, you need to have a long hard look in the mirror.

In my heart, Aotearoa New Zealand is the champion of creatives, protecting people’s right to get what they’re due from their good ideas.

AI is the antithesis of that and few here seem to care.

Again, it’s not the tools I have a problem with, it’s the systems. OpenAI says it simply had to steal to move fast enough, but move fast enough to give us what? Half-baked cash furnaces?

To quote someone I don’t want to name for privacy reasons: “AI companies have normalised production products simply not working.”

After all the environmental damage they’ve done, the mistrust they’ve sown, the creators they’ve trampled on, the false claims they’ve made, the promises they’ve broken, the money they’ve burned, the questionable politics they’ve become involved in, and the arrogance they’ve embodied – after all that, what do we have to show for it?

Bland first drafts, untrustworthy advice, a few useful summaries, and a lot of wishful thinking.

I love technology. I don’t think I’ll ever get over the thrill of seeing something I’ve known my whole life being done in a new, faster and better way.

And while I’m legitimately impressed by some of the things LLMs and GenAI can do… I just can’t get this sour taste out of my mouth.