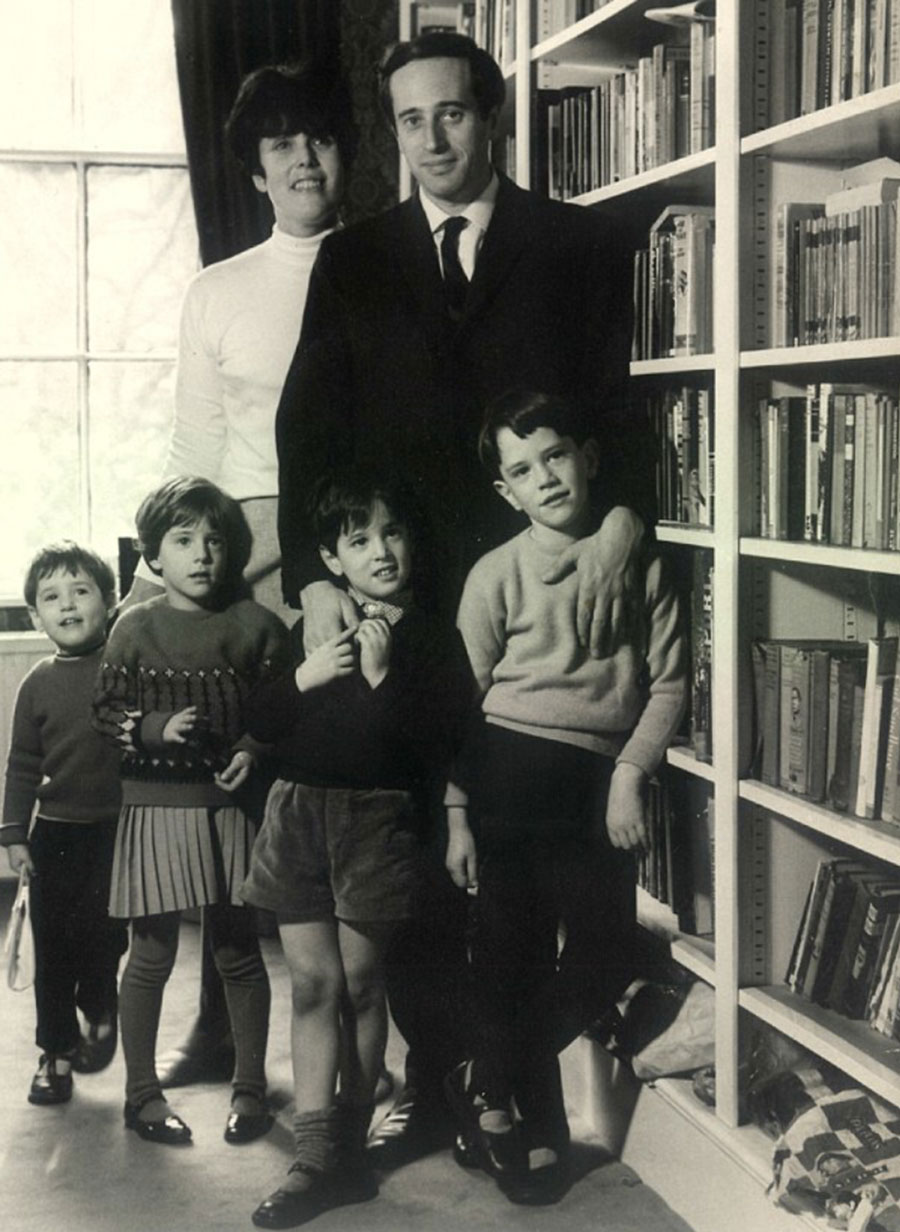

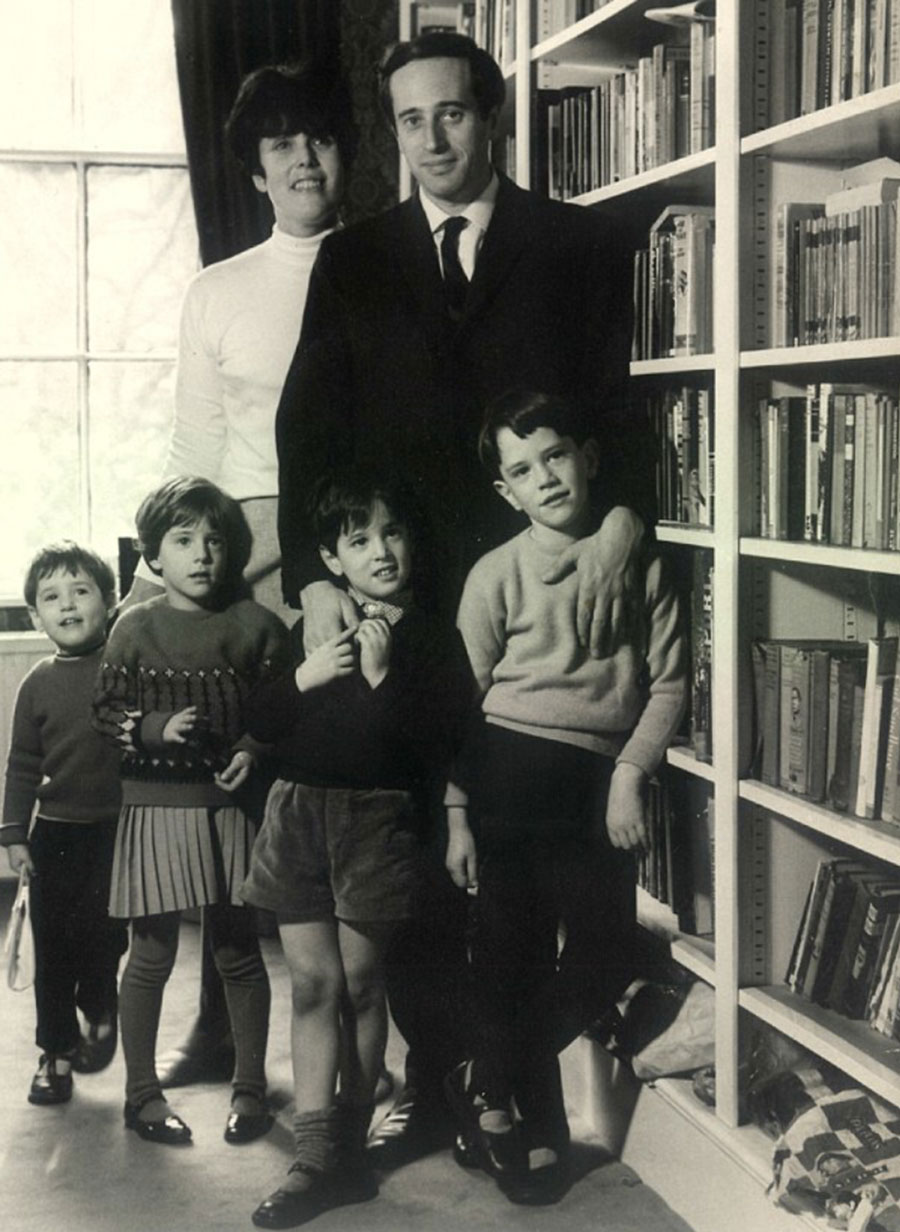

Brian Glanville with his wife, Pam, and four children.

The train to Holland Park

12th June 2025

Steve Braunais meets his literary hero, the ‘doyen’ of football writing, Brian Glanville

It was a dark and stormy afternoon. Rain blew in sideways off the Thames. It was hard to tell whether the thick piles of rags outside the Tube stations had homeless people inside them. I was looking for a house with a blue door in Holland Park. The neighbourhood seemed quite posh, with Russian nannies pushing expensively upholstered prams, and dressed pheasants hanging on hooks in butcher shop windows. I was very nervous, a wild colonial on my way to meet a distinguished man of letters, a legendary figure, a hero — why is it that we are forever being scolded to not meet our heroes? What do we expect, some boring paragon of virtue who only exists to please us? I loved every second of my appointment that afternoon, especially the weird and actually quite harrowing seconds.

Brian Glanville died in May. It did not exactly come as a shock — he was 93 — but his death came with a rare and special kind of sadness, likely for tens of thousands of people in various corners around the world. I read tributes from admirers in India, Singapore, the US, someone in Russia. His last paid newspaper work was writing obituaries of football players. I had often imagined him these past few years sitting in the splendid mess of newspapers and books in that dark London home with the blue door, tinkering on the typewriter keys to compose his own obituary. It was the sort of thing he might have done for fun. He had a very intense sense of humour. I wonder if he was kind of mad.

Steve Braunias

We met when I won a fellowship to Green College in Oxford to write a research paper on the history of football literature. Every dinner in the dining hall at Green was a torment; Dons of great distinction would sit next to me, and over our mash and peas and pale fish, they’d eagerly ask what academic work I was pursuing. They loved meeting new people, loved the sharing of ideas. They hated my answer. They found it as revolting as the fish. Football was for idiots and football literature was oxymoronic. “But,” I would simper, “have you ever read Brian Glanville?”

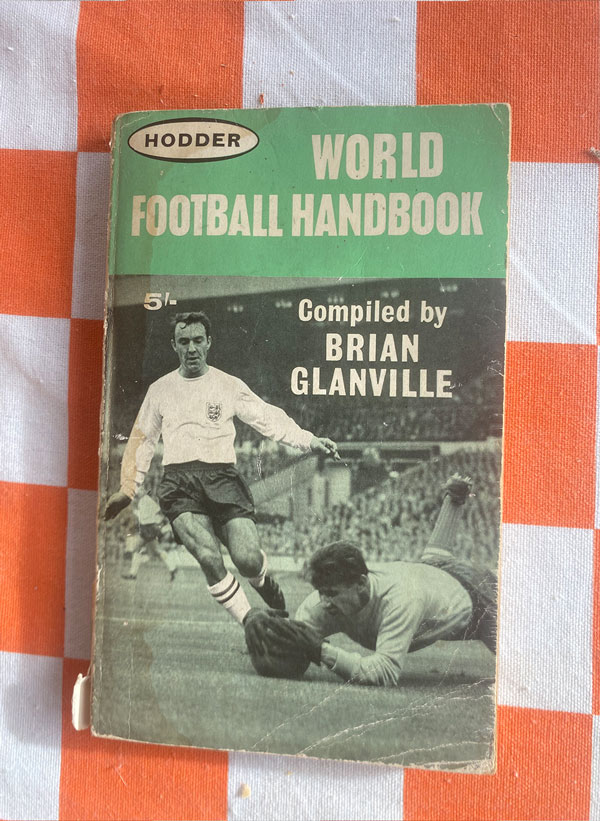

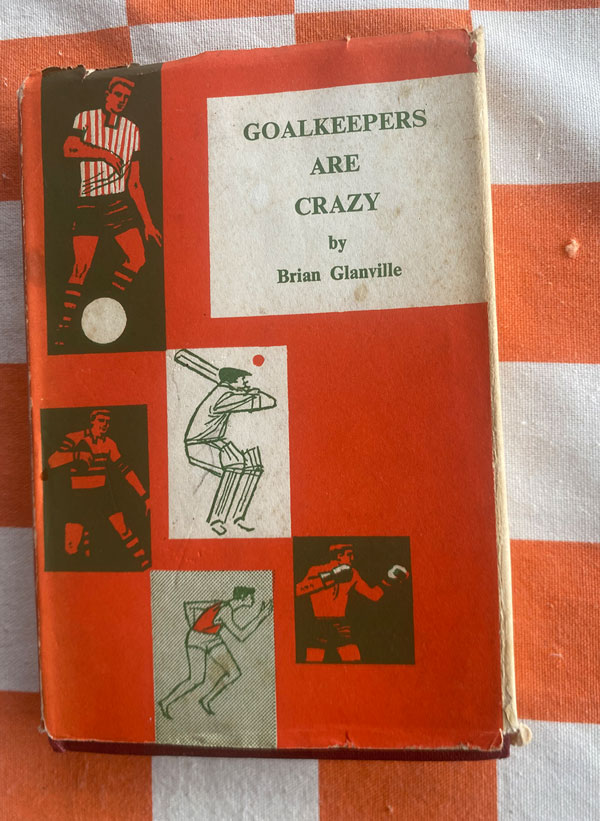

As early as 1961, Glanville sighed in the Introduction to his anthology of soccer writing, The Footballer’s Companion, “We have been told, ad nauseum, that football is a game without a literature.” It wasn’t true then and his own contribution in the following years provided a massive corrective. Glanville was the dean of football writing, its most elegant correspondent, a moody, sometimes grave conductor of artful and eccentric prose who would very often burst into Latin, make obscure literary allusions, quote from Groucho Marx, tell everyone to get fucked and run his thoughts in long, long sentences like train carriages rattling around bends and through tunnels. No one wrote like Glanville. He was a newspaper man with the Sunday Times and he also wrote a monthly column for World Soccer magazine, which I tore open every month growing up in Mt Maunganui to read the latest experiments in malice and wit from Glanville — his audience formed the international community of the tens of thousands who have mourned his passing, many of them acknowledging he was the reason they decided on a career in journalism. I am in the exact same boat. His thrilling prose deceived me into thinking it was a noble profession, and I owe 45 years of artistic failure and working for idiots to Glanville. He, too, was familiar with the disappointments of the trade. He put it very passionately and eloquently towards the end of our encounter in Holland Park.

We met at 2. Winter was coming. Autumn had barely got a look-in that year. The street lamps were lit, and shone on Glanville’s blue door. He opened it and stood there as a legend of my childhood made real with his long face, his sharp nose, his dark eyes, a man as thin as a broom who swept me inside and into the front room. We sat across from each other in old armchairs. Weak daylight crept past the lace curtains. He was flattered to receive a fan from New Zealand and bemused that Oxford was indulging my project about football literature, but he had got used to praise, worship, stuttering adulation. Of course he knew he was widely regarded as the sport’s best writer, and not merely as a columnist or match reporter. He had written essays, documentaries, also short stories and novels about football. The fiction had a mordant tone. His characters were tragics and worriers, lost and neglected, like his little masterpiece ‘The Man Behind the Goal’, a 1963 short story about a transient who goes to a park to kick the ball back to players when it goes out. He ends up in a familiar place in Glanville’s fiction, somewhere he had spent some of his formative years: a hospital bed.

“Pam, this young man is from New Zealand,” he said. “Can you make us a cup of tea, love?” His wife said yes of course, and returned with tea and a plate of three biscuits about an hour later. By then the pale light in the room was very dim indeed.

”His thrilling prose deceived me into thinking it was a noble profession, and I owe 45 years of artistic failure and working for idiots to Glanville - Steve Braunias

Brian Glanville

On the day I learned of his death, I mooched into the front shed on my Herne Bay estate and picked out copies of World Soccer that I have kept all those years. There was Glanville sounding off, remembering obscure games he had seen at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, busting out Italian riddles (“Se faveca cappeli, nascomo senza teste” – something about heads and hats); and there he was in the December 1972 issue, making the rare compound of football and the Bloomsbury set: “Bertrand Russell and Clive Bell were envisaging, several decades ago, a world better than one in which people went off to watch football matches rather than cultivating one of Mr Bell’s vague but beloved ‘good states of mind’.”

I have a row of Glanville books in the shed and another row inside my house. There was his remarkable New Journalism experiment, plainly influenced by the great American writer Gay Talese, in his 1961 profile of Stanley Matthews, in Glanville’s Selected Writings (1999). There was his The Rise of Gerry Logan (1963), the first football novel ever written, a close portrait of the chancers and dreamers inside the sanctums of professional football: “He reached out slowly for his gin and tonic. His fat, white hand, shaking, made the journey with enormous caution, closing at last around the glass, and bringing it back in careful triumph.” The character is a drunk sports writer. Glanville mocks his florid prose, his manic energy, and wonders, “What worm was it that gnawed at him, drove him to self-destruction? Disappointment?” They were very good questions.

I also consulted Glanville’s memoir, Football Memories (1999). It’s barely a memoir. He writes well about his childhood, and his admission as a young man to a sanatorium to treat his TB. He later got sent back to hospital to have a bone graft in his back. He also brings the reader with him, when he was 18, to a flat above a trucker’s café on the North Circular Road around London, where he interviews a deaf ex-footballer (“He had no humour to speak of”) to ghostwrite his autobiography. “His wife made us mugs of strong tea, and thick cheese sandwiches.” There’s an exciting sense of Glanville making his way in the world, and realising he had a gift for language.

But he gives the rest of his personal life the slip. There is an occasional stray line remembering he has a wife called Pam and that they have four children, two boys and two girls. His eldest son Mark Glanville became an opera singer. He also wrote a memoir and as if to make up for his father’s reticence, he shares intimate details of his sex life, at one point confessing he repeatedly had anal sex with one of his girlfriends out of ignorance — he thought it was her vagina. Is this a common mistake? Glanville junior is a strange guy; the core of his book The Goldberg Variations (2003) is another confession, that he became a full-on football hooligan, violent and adrenalised, every Saturday a life-or-death thrill. He put on a Cockney accent, and when he won a place at Pembroke College at Oxford, he explained to his yob mates that he was about to go to prison to serve a four-year sentence for murder.

Glanville junior also takes readers behind the blue door at Holland Park. He presents his father as hilarious, performing stand-up routines every night around the dinner table, but also full of rage and buried sensitivities — and desires. Pam (“Poor Mum,” weeps his sister Liz) confides in him “about Dad’s womanising”. Then he tells a story like something out of his father’s short story collections. English rain, all the lonely people lost in London … He writes, “I was standing under a bus shelter on Finchley Road trying to gain some protection from the pouring rain when I noticed a woman with short black hair and heavy mascara, umbrella in one hand and in the other — I could scarcely believe it — a copy of one of Dad’s novels. I’d never seen anyone reading his books in public before. It made me proud. But just as I prepared to step forward to tell her who I was she glanced at me, and I instinctively realised it was the wrong thing to do.”

He squints through the rain. “On closer examination I noticed she was only at the start of the book. Perhaps it was only the beginning of the affair. She seemed tense and unhappy. I wondered who she was and how he’d met her.”

I was given Brian Glanville’s phone number by another football writer in England. He didn’t speak very well of him. He described him as a dark spirit, and a penny-pincher; he told the story of seeing Glanville stopped over at Tube stations, looking on the floor for dropped railway tickets that he could pick up and use. I felt very defensive about these comments. I loved Glanville for his writing, but also for the brave, intellectual, more than slightly crazed character that it revealed. There was so much to him. He was a complicated man and interviewing him that afternoon was like a tour through some of the doors of his personality. The doors swung open and slammed shut; he was so moody, hostile one second and considerate the next, always opinionated, always on edge.

Pam seemed nice. The tea was weak and Glanville wolfed all three biscuits. I could barely see him as the light packed up and took its leave from the small dark front room. It was getting onto just past 4 when he finally turned on a lamp. It had also got quite cold but there wasn’t a hope in the world he would turn on the heater. “They rob you, the electricity companies,” he said.

It’s entirely possible he was wanting to get rid of me and decided on a tactic of literally freezing me out. He never spoke personally; he deflected any invitation to examine his life. He preferred to tell stories in a range of accents — Geordie, Cockney, Scots, Chinese, Italian — and laughed loudly at these farces, these skits; he was often in high spirits, but there were times when his mood fell, and it really descended when he flung a hand towards his desk, with its piles of papers and quite a few copies of his books (I left with a stack of them, all signed in his neat hand), and announced, almost shrieking, “What has it all been for? What has it added up to? What is the sum of all this writing which you, a Kiwi is it?, have come from New Zealand to speak of?”

He leaned closer, that long face whitened by the one solitary lamp in the darkness of dusk, and shared the answer. “Nothing. Nothing!”

I left not long after. He closed the blue door. There were no lights on in any of the other windows — where was Pam? Night had fallen. I had spent the afternoon with the writer who meant more to me than any other author, and I was happy, almost ecstatic. His dramatic and nihilistic verdict about himself was quite wrong. His writing added up to something immeasurably good. I think he knew that, too.