Japanese school lunch

The Japanese school lunch – and lessons for Aotearoa

19th June 2025

Kyushoku: the deep culture of the Japanese school lunch, and lessons for Aotearoa.

By Dr Renee Liang

Last Friday, if you’d been on the 18th floor of the Majestic Centre on Willis Street, in Pōneke Wellington, you would’ve been treated to an endearing sight: men and women in suits rolling tables into place, running to the bathroom to wash their hands, lining up like kids to receive a ‘real’ Japanese school lunch, then waiting ready at their tables to express appreciation before diving into yummy food.

The Embassy of Japan has entered the school lunch conversation in the most Japanese way possible: by graciously inviting everyone to a meal. MPs, media, school principals, health experts and business leaders were invited to a ‘classroom lesson’ followed by lunch created by Chef Yamaguchi, who cooks for Ambassador Osawa.

It was a perk I never expected when I agreed to write a health column, but in this job you learn to roll with tasty opportunities.

While embassy staff were at pains to point out that they did not want to criticise Aotearoa’s school lunch programme, or claim that their model should be replicated here, there were many lessons we could apply to the New Zealand context.

Our school lunch programme is just a few years old, whereas Japan’s has been running since the late 1800s and has changed and adapted with the times. Their modern school lunch programme is something to be proud of: although not compulsory, 99.1 percent of all schools in Japan take part. The programme is enshrined in law. Health, education, and agricultural ministries communicate and collaborate (fancy that) to support the different components that form a truly holistic programme, encompassing topics such as nutrition, child development, societal change, food science, sustainability, and environmental protection.

While the programme is not free (parents pay around 250 yen – NZ$2.90 – per day for kindy and primary school student lunches, and around 300-450 yen – NZ$3.50-$5.20 – for junior high and high school lunches) there are provisions in social welfare to support families so all kids get a hot meal regardless of their circumstances. It’s considered important that everyone eats the same food, together at tables in their classroom, and teachers eat with them too.

Schools are supported with local and nationally administered grants for infrastructure such as kitchens, and for many schools, meals are prepared on site by chefs, overseen by nutritionists, and emphasise locally sourced seasonal ingredients. To ensure food safety, all meals are cooked (sushi and sashimi are not on the menu). Nearly 90 percent of Japanese students claim to love their school lunches and some schools are famous for the quality of their food.

The universal school lunch programme in Japan has a moving origin story. While a private elementary school in Yamagata was the first to feed its poorer students lunch in 1889, it was in the ravages of post-Second World War Japan that the national school lunch programme was born. Ambassador Osawa said poor students, shamed by their meagre lunches, would hide behind makeshift screens of newspaper and slow down their chewing so they would ‘finish’ at the same time as other students who brought multiple courses (the norm for Japanese meals). Teachers hated watching this, and also saw that starving kids couldn’t focus on learning. At the same time, the government was becoming concerned about poor nutrition and health in the general population, so offering a standardised meal to every kid made good sense.

A tasty meat stew ladled over rice with a salad on the side and a glass of milk

By the time Japan’s economy started booming in the 1960s, the value of the school lunch programme was so evident that further laws cemented its role as a key educational tool.

In 1946, the universal school lunch programme was launched, becoming law in 1954. Subsequent Acts in 2003 and 2006 further entrenched the ideals of the programme – that lunch should also support good citizenship, teach societal responsibility, and that ‘shokuiku’(食育) or food education, should foster lifelong habits around healthy eating.

Shokuiku means much more than just nutrition – children are encouraged to think about the whole ecosystem and culture of food, and practise ‘mindfulness’ while eating. The expression ‘Itakadakimasu!’ (“I humbly receive“) for example, is said habitually by adults and children throughout Japan before every meal, and ‘Gochisousama deshita!’ (“it was a feast“) after a meal – akin to grace or karakia, but much briefer allowing us to get quickly to the eating part.

Parents take an essential role – regular communications from the school including a newsletter and a monthly menu, contain instructions for fostering shokuiku’s attitudes at home, including getting their kids to practise fiddly things such as eating around bones or peeling fruit (what my Cantonese mum would call ‘not being lazy’).

The monthly menu – which covers international dishes such as pasta and burgers as well as Japanese standards – contains caloric information and crucially, ingredients so that allergies can be avoided.

The translated copy of a real newsletter we were given included instructions such as, ‘Sit with good posture. Take appropriately sized bites and chew thoroughly. Engage in conversation appropriate for mealtime. Handle tableware with care.’

Renee Liang

Although homilies might fall a little flat with some of our feistier kids, my tablemates – among them a Rotorua business leader, journalists, the Deputy Ambassador and a nutrition researcher – agreed that the general principles of shokuiku would resonate in our culture too. After all, most New Zealanders come from collectivist cultures that embrace eating together and respecting the labour of the producers and preparers of our food.

My friend Jon Walsh, born and bred in Bayswater, Tāmaki Makaurau, moved to Japan for love and now teaches urban farming at international schools in Tokyo. The school lunch programme extends to a much wider curriculum around food, including gardening, cooking, and field trips to food preparation facilities. Natural disasters in both his home countries got Jon thinking about food security. Since then, his company Business Grow has trained thousands of students at 17 schools over the last 14 years.

Back in 2010, he said he had no interest – or experience – in growing food.

“All that suddenly changed when the Tohoku earthquake/tsunami disaster hit in March 2011 and killed around 20,000 people. That shock hit about two weeks after a deadly quake hit the city of Christchurch in my native New Zealand.

“These two quakes had a huge effect on me and made me think: If a quake that size hit Tokyo and lots of roads get blocked and food stores are destroyed, where would we get food from? I had no answer, which was very scary.

“Many people who have emergency supplies would run out within days and these supplies would quite quickly become a pile of empty cans, boxes, and bottles. We can’t eat these. I wondered, then what?”

Jon works hard: before he starts a programme (which lasts months as children grow food from seeds before harvesting and making their own salad ‘lunch’), he discusses with teachers how to integrate relevant aspects of the school’s curriculum into his programmes. International schools don’t run the national school lunch programme so funds are needed to include it. Jon often does extras such as free workshops and demonstrations, helping stoke schools’ interest so they can raise money for more equipment such as planter boxes and soil.

“So far, four international schools in Tokyo have integrated my urban farming programmes into their curriculums, something I am incredibly proud of. None of these schools had urban farming programmes before I offered them one.”

Almost all elementary (primary) schools in Japan teach students how to grow tomatoes, sunflowers, and Morning Glory flowers.

“If you go to any classroom in Japan, you’ll see containers and pots of seedlings outside the rooms. But after elementary school, their gardening training stops.

“I specialise in teaching students how to grow vegetables, herbs, and flowers. I also encourage schools to donate a portion of the food students grow to local food banks as part of the Food Havens strategy I launched in 2013. In contrast to most food donated to food banks, which is processed and packaged, Food Havens provides fresh food to supplement the diets of those with lower food security.”

All in … Serving a Japanese school lunch is a community affair (Left)

Deputy Ambassador Oshima, far right, and other guests are served a Japanese school lunch (Right)

The seven main goals of ‘shokuiku’ are: to maintain and promote health, to respect nature and protect the environment; to understand the role of food producers, to understand how food is distributed and prepared; to appreciate food traditions; to eat healthily; and to learn social norms by eating together.

At my table, when I said I’d been taught to eat every last grain of rice on my bowl, one of the journalists shared how as a child in Japan she harvested three grains of rice from her plant and insisted these were cooked and eaten. The Deputy Ambassador Oshima who sat across from me smiled ruefully and admitted that in his own school days, he was one of the slower eaters and was often one of those still eating when classes started again after lunch. But, he knew the teacher would be angry if he didn’t respect the food. “The food is much tastier these days,” he said.

In Japan, kids as young as 6 take turns as lunch monitors, donning white jackets and caps to fetch the catering trolleys from the onsite kitchen and then rolling these to classrooms where others set up tables. Jon’s daughter Serena, now 17, grew up with this model.

“Lunchtime, which involves serving and eating, is about 40 minutes. All students take turns at being Kyushokutouban (lunch monitors) – four to six people for a week, then they rotate. It’s a fun role.

The trolley from the school kitchen contains a large container of rice, another of soup, plus milk, salad, and fruit, and plates and chopsticks.

“This is joined to a trolley that lives in the classroom and this makes a serving surface. Kyushokutouban line up on one side of the trolleys and serve food to their classmates who line up with trays. When you first start out, you have to work out how big a portion to serve to everyone so that the food doesn’t run out before the last student. But if a girl likes a boy, she might secretly give him a bigger portion. Afterwards, everyone is expected to clear away their plates and clean up.”

Unlike school canteen offerings in NZ, there’s no ‘junk food’ like pizza or cake. This makes mealtimes at home easier, too, and it’s such a great way to mould the palates of an entire country. Maybe the famously excellent cuisine and the longevity of the Japanese owes something to Kyushoku.

When I dig into my meal – a tasty meat stew ladled over rice with a salad on the side and a glass of milk – I notice how lightly flavoured the food is. It’s tasty, just not as spiced or salted as I’ve become accustomed to in New Zealand. My new Japanese friends shake their heads when I ask if seasonings are provided on the communal school tables. I realise later that is probably because of the careful matching of the meals to nutritional standards, which also means limiting salt intake and ensuring micronutrients are covered. It also means that kids try things they might not think they like – Ambassador Osawa admits he learnt to enjoy eating carrots at school.

An interview with a Japanese school student about lunch

Would such a structured school lunch programme work in a NZ context? I asked an expert – Jon’s daughter Serena, who has attended school in both countries.

What’s your favourite lunch?

Kinako agepan (fried bread with kinako (finely ground powder made from roasted soybeans), because it’s sweet.

Has the school lunch programme set you up well for looking after yourself as a young adult?

Yes. We learn how to serve food efficiently, and serve it with and to others: we have to think what to do next and about the roles we are asked to perform as Kyushokutouban. If someone drops their plates or chopsticks, we learn to help others by giving them another pair of chopsticks or cleaning up.

I grew rice and other vegetables in the school garden, and the food we grew was served for our lunches. Once a month, students were served lunches from different countries, Thailand, Indonesia. I think New Zealand schools serving foods from different cultures is a great way for students to learn about different cultures’ lunches. Bringing lunch from home limits the students’ ability to try other foods. Though New Zealand is different, it’s normal to be from many other countries while in Japanese schools students are 98.5 percent Japanese. So new foods might be one of the ways we learn to be more accepting of other cultures.

Apart from expressing crushes, what are some of the other surprising, possibly unintended, effects of the school lunch programme?

Every boy who tries to make other kids laugh while they are drinking milk (served with every lunch) will probably be hated. Some kids do “okawari” (taking a second helping, or refill) too many times, and even try to get leftover food from other classes.

When a homeroom teacher doesn’t like a food, like bananas, but still has to eat the food they hate to set a good example, students might troll them. I’ve seen students hold a “banalympic” [banana Olympics] and some kids will hold bananas like a microphone and commentate on the teacher eating the banana: “And now she is peeling her banana”, “Now she is taking the first bite!” or ask the teacher questions like “How is the flavour?”

Since you’ve attended school in both New Zealand and Japan, do you think the Japanese school lunch programme would transplant well to NZ?

Yes, but there might be some problems. It might be a bit difficult to move the catering trolleys from the kitchen to classrooms because the corridors [at Bayswater Primary] are narrow. Also, classes have carpets unlike wood or lino floors in Japanese classrooms, so it might be difficult to clean up any food. But I think in terms of having students take on responsibilities for serving and cleaning up, there would be no difference.

While it’s clear that Japan’s model wouldn’t be able to be replicated easily in NZ – their programme has evolved over many decades and been incorporated into school and industry infrastructure – there are many takeaways we could learn from. The community values of respect and even elevation for farmers and others making our food are the same here, and we also value good food and healthy active lifestyles.

Investing in similar philosophies with locally sourced, seasonal produce would go a long way to countering the altered palates inflicted on us by corporate marketing campaigns and international chains, and would at its heart be a very ‘Kiwi’ way of declaring independence and affirming our identity.

As I walk away from the Embassy with a full tummy I have an actual takeaway as well – the serving ladies allowed me to take an extra parcel of rice, which was mummed up by my kids that night. Itakadakimasu!

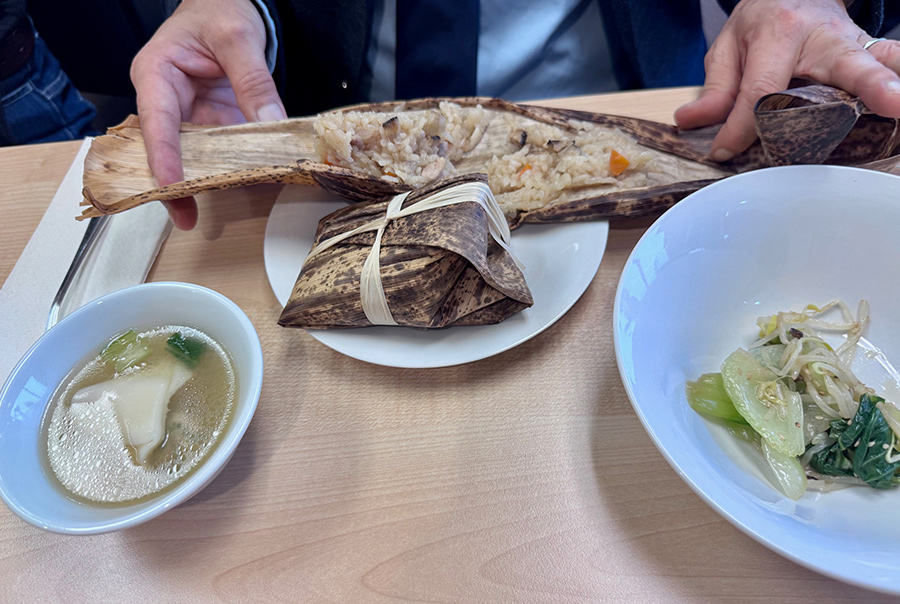

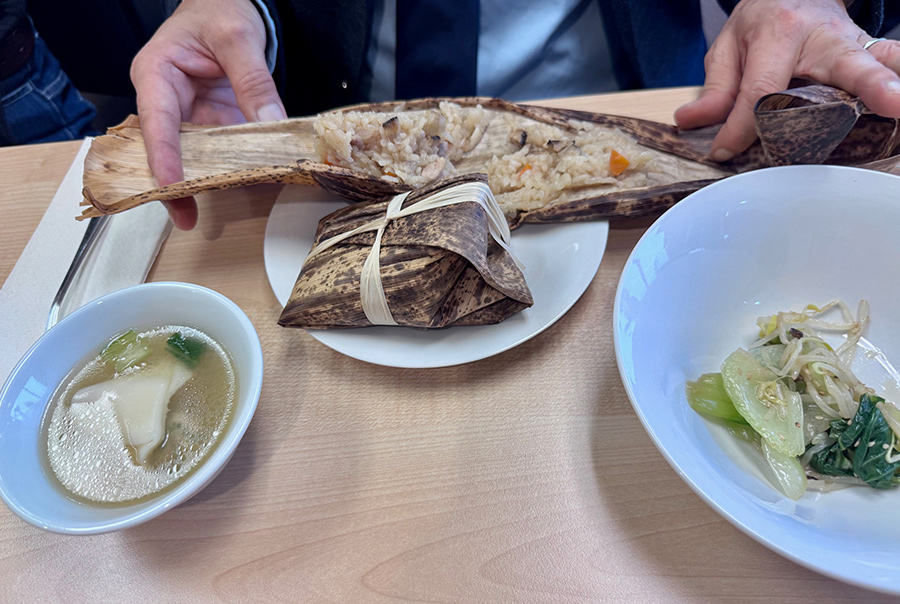

Our meal choices:

• Tea Day Menu: Edamame Soboro (minced) on rice, Kenchin (vege) soup, seaweed salad, matcha kanten (jelly).

• Children’s festival menu: Chimaki (rice with dusted mushroom and chicken wrapped in bamboo leaf), wonton soup, sesame salad.

• Hayahsi (beef stew) on rice, konjac salad, mandarin.

Jon Walsh’s Business Grow website.