Jungle Drums

10th July 2025

Gangs, popular culture and moral outrage collided spectacularly in mid-1950s Aotearoa.

By Scott Bainbridge

1955 had been a tumultuous year for Auckland bodgie gang, the Angels. Their Friday night run-ins with arch-rivals the Vultures were making regular front page news. The Vultures, with their penchant for roaring up and down Queen Street on their motorcycles were bringing unwanted attention from all sides.

Tensions had been simmering for weeks. The killing of bodgie Johnny McBride at Ye Olde Barn in July, his killer, Albert Black, in jail awaiting execution was the last straw.

Emotions spilled over on Friday night 4 November 1955. What started as a planned march by the gangs, united for the first time, resulted in an event some recall as the Civic Square Riot. The purpose of the march has been forgotten over time, but one remembers it being in protest of Black’s pending execution.

To provide background. In Patched: The History of Gangs in New Zealand, Dr. Jarrod Gilbert wrote the roots of the patched gangs we know today can be traced back to the youth gangs of the 1950s, comprising bodgies and milk bar cowboys. Although many confused the two, both sects were very different from each other. Bodgies wore long coats, black stovepipe tweeds, black crepe-soled shoes, white or coloured shirts, bootlaces worn around the neck, and DA (ducks arse) hairstyles with the Elvis quiff. This style was adopted by the Teddy Boys of London’s East End, many of whom worked as ship stewards and sold their wares at New Zealand ports to the young guys who wanted to stand out from the drab greys and browns. Despite their similarities, bodgies hated the comparison. During Black’s trial, Angel, Michael Sinclair explained “We do not like to be called Teddy Boys. We regard this an insult.”

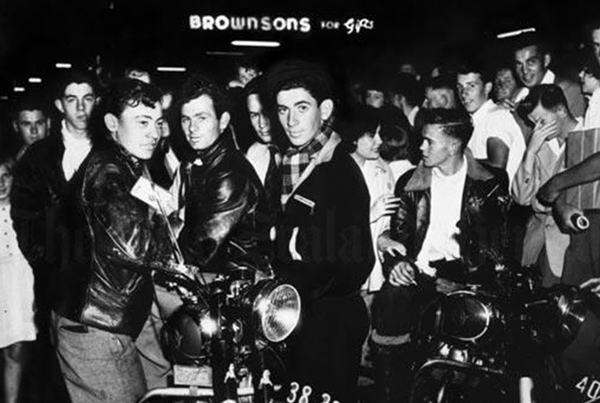

Queen Street 1955

By contrast, the Milk Bar Cowboys, like the Vultures, were rougher. They had motorcycles, dressed in army coats or leather jackets, peaked train-driver caps, collar-length hair tied with coloured bandanas, blue jeans (which were hard to get in 1955) rolled up to the shin, white socks and flying boots with steel-cap hobnails which would emit sparks when boots were dragged along the road when riding. They carried sheath knives in their belts and used sharpened bicycle chains as weapons in the rumbles they eagerly initiated.

“We were from a dangerous side of the tracks” laughed Lloyd Herewini when I interviewed him in 2014. “Every Friday night, we cruised around the city on our bikes and parked en masse outside Curries Milk Bar at 142 Queen Street. That was our hangout. The only thing we had in common with the Angels was that we liked the same music.”

The Angels membership was restricted to young men. Their girls, or ‘widgies,’ were considered ‘arm candy.’ The Vultures comprised 11 boys from working class backgrounds and had one full-fledged female member. Anna Hoffman recalled her best friend she had known from school. “Yvonne Skudder was a stunning brunette with a lovely face, but boy, you wouldn’t want to cross her. She was black belt in judo, years before martial arts became a thing. Von worked at the Picasso Café as a lounge jazz singer in the vein of Anita O’Day. When she left the stage, she hung around the door as security to throw out drunks. They would give her shit, but she always had the last laugh when she tossed them out into the street. She never lost a fight.”

Herewini recalled; “Yvonne was with Mike Nepia. He was the one who started the Vultures along with Jake Kelliher. Then me, Mike Reizenstein and a few others joined. We were just a group of young fullas that worked hard during the week and rarked it up every weekend. You could say we were like Fonzie from Happy Days but rugged round the edges. It was the newspapers that hyped up the notoriety. It started with that fuss down Lower Hutt.”

In 1954, storm clouds gathered. The murder trial of Heavenly Creatures, Parker and Hulme referenced Pauline Parker’s diary entries, filled with American gangster-movie slang, startling authorities who believed these entries hinted at a link between the influence of American popular culture and its potentially corrupting effect on teenagers.

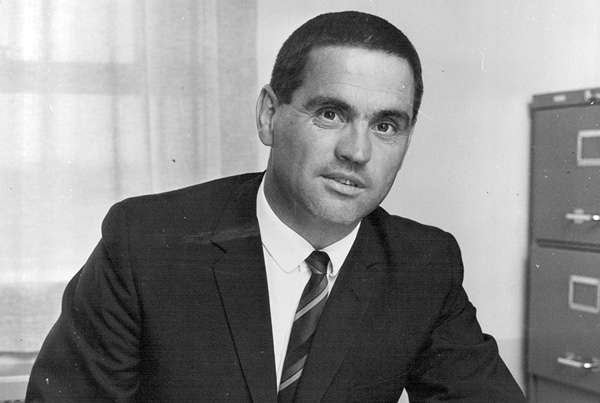

One night, around the same time, a concerned mother rang police reporting her 15-year-old daughter missing. Police found her at a house in Lower Hutt with about 12 motorcycles parked outside. The girl told police she hung out with the Milk Bar Cowboys at Elbe’s Milk Bar and admitted having sex with them to gain popularity. It was the tip of the iceberg and exposed similar teenage sex scandals elsewhere. These caused a national furore frightening conservative parents all over the country. In response, the government engaged retired lawyer, Dr Oswald Mazengarb, to chair a Special Committee on Moral Delinquency in Children and Adolescents. Among the many conclusions reached, Mazengarb blamed the influence of American popular culture, such as comics and violent ‘pulp’ novels, as undermining adolescent morality. In All Shook Up, author Redmer Yska wrote crime novels from Mickey Spillane and others were banned overnight, as were comics featuring characters like Dick Tracy, Buck Rogers and the Lone Ranger – because it was an offence to wear a mask in a public place in New Zealand. Attorney-General and moral crusader Jack Marshall instructed Justice Department clerks to purge the shelves of newsagents and bookstores in their lunch breaks.

Lloyd Herewini, “The government thought they knew what was good for you. If you read a Spillane book today, it is tame in comparison to the latest crime novels.”

Milk Bar Cowboys 1956

AG Jack Marshall 1955

The Vultures had been looking forward to watching the movie ‘The Wild One,’ about a motorbike gang starring Marlon Brando, but it was banned (finally lifted in 1977). Within a year, movies like ‘Rebel Without a Cause’ and ‘Blackboard Jungle’ with its rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack were heavily censored. In their books, Gilbert and Yska recalled the Cheers hit song ‘Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots’ suffered the censor’s fate as did other innocent songs whose titles or lyrics could be misconstrued.

Angel, Pooch Quintal agreed with Herewini that the actions by Jack Marshall’s lot were unreasonable. “The stupid thing was that jukeboxes played the songs the radio banned, and the seamen were bringing over all the crime books so they weren’t that hard to get.”

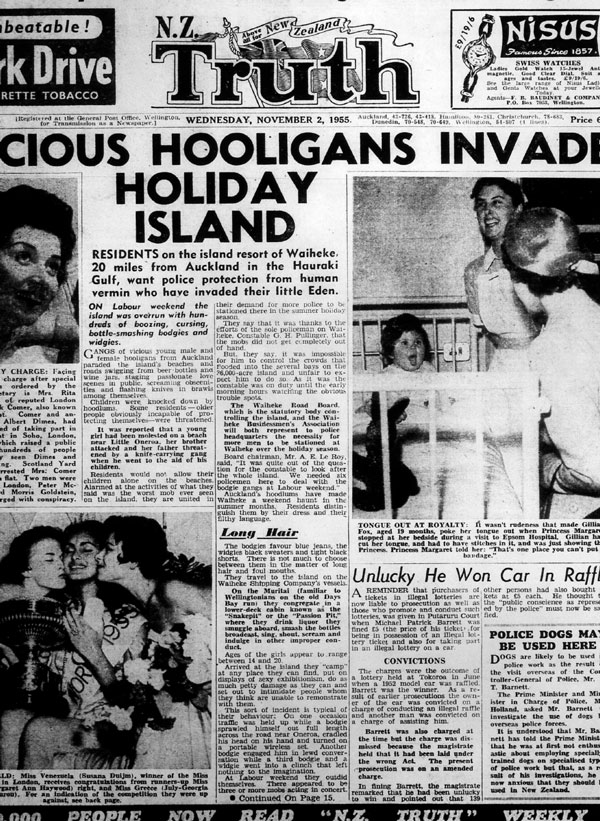

Herewini: “I can’t say American culture was influential. We were just a group of guys who liked motorbikes, and the media hyped up our antics to sell newspapers. Over Labour Weekend ’55, there was a dance on Waiheke Island, so we rented a bach. We all got on the piss and had a great time. Then next week’s Truth front page headline told how the Vultures ran amok, smashing the place up, beating up little old ladies and knocking down kids. I was like ‘who did all that?’ and then reading it was supposed to be us. We found out later there was another group called the Hi-Bars, and they were drunkenly hassling people on the beach, but we got the blame.”

That’s not to say the Vultures were saints. Late night shoppers would gather and watch in awe as they tore up and down the CBD and then line their bikes outside Curries Milk Bar. Up the road, the Angels held court at Ye Olde Barn at 366 Queen Street. Inevitably, there were run-ins, rumbles, usually petty differences, and provocations, insulting a girl or worse – one’s mother. If one guy got jumped, revenge would be swift. Fights involved fists, broken bottles, boots, bike chains and even stiletto heels. Both groups carried knives, but these were only used for show.

Pooch: “The fights were brutal, but it never got to the point anybody was seriously stabbed. Remember, we had capital punishment, so no-one wanted to hang. There were some bloody awful injuries though. I had deep bike chain marks across my back for months.”

‘Poogie’ hung out with the Angels and was slightly younger. “I idolised Pooch and the Angels and they tolerated me, I guess. I was told if I wanted to join, I’d have to do something to the Vultures. I was given a screwdriver and instructed to puncture some of their bike tyres outside Curries. I couldn’t bring myself to do it because I’d get caught and given a hiding. Some of the Vultures were close rellies, so I knew if word got out, I’d get another thrashing at home. Some nights later, I was with another mate in Ponsonby and saw two bikes parked up a side road. While my mate stood lookout, I punctured both their tyres and skedaddled out of there fast. I found out they weren’t Vulture bikes, so it still didn’t get me into the Angels.”

Marlon Brando

Truth

The regular weekend fracas was a nuisance for police as gangs outnumbered the beat constables. Tired of cleaning up and fixing broken windows every week, business owners implored police to do something drastic to curb the ‘guerilla warfare.’ Sub-Inspector Parker engaged the Army Department who agreed to augment patrols and deputise army servicemen from Papakura Military Camp to quell disturbances. While good in theory, it had the opposite effect. The servicemen hunted in packs, openly provoking the bodgies into scuffles. There was even a faction determined to grab hold of them and cut the ducks arse off the back of their hair. The army caused more headaches for police. It was the catalyst for an unlikely truce and call to arms.

In November 1955, Pooch Quintal was serving an 18-month stretch in borstal for car conversion. “Every week there was someone from Auckland being sent down, so I got my news updates from them. Paddy was about to be hanged and Marshall denied his appeal, just like he had refused those of Freddie Foster and Ted Te Whiu. Then those two young blokes, Ruka and Harris were stitched up by the Jacks [detectives]. We had such a burning hatred and disrespect for the authorities.”

Poogie: “The Ruka-Harris case had a profound effect on every young guy [see next month’s North & South]. It was a culmination of all the shit that happened, that someone, it might have even been Ray [future strip club entrepreneur, Rainton] Hastie, said enough’s enough and suggested to the Vultures that we join forces and march from Ye Olde Barn to Curries Milk Bar as a kind of show of support for Paddy.”

Word got out something big was going down on Friday night 4 November. The bodgies were going to ‘raise merry hell.’ In a hastily convened police conference, it was decided everyone available would be out in force, including tough detectives Arnold Kyne and Edward Perry, the latter an ex-navy light-heavyweight boxing champion. Chief Detective Brady could only muster 21 police. Reluctantly, he reached out to the armed services again for backup, securing 30 servicemen and provosts from the army and Air Force. Perry managed to secure off-duty navy conscripts from the HMNZ Philomel eager to crack heads. The combined servicemen were only required if the situation got out of hand.

At 7.05pm, groups of young guys began gathering at Ye Olde Barn. Lloyd Herewini was one of those who turned up. When asked about the night, he was reluctant to share, but stated. “It was all a setup. The jacks were out in force. There were patrol cars opposite Ye Olde Barn. It was always going to be bloody.”

The servicemen assembled at Civic Square, not far from Ye Olde Barn. Late-night shoppers sensed something was about to happen and gathered on the footpath outside Atwaters Music Store jeering at the bodgies. The next day was Guy Fawkes, and some larrikins tossed firecrackers into the crowd.

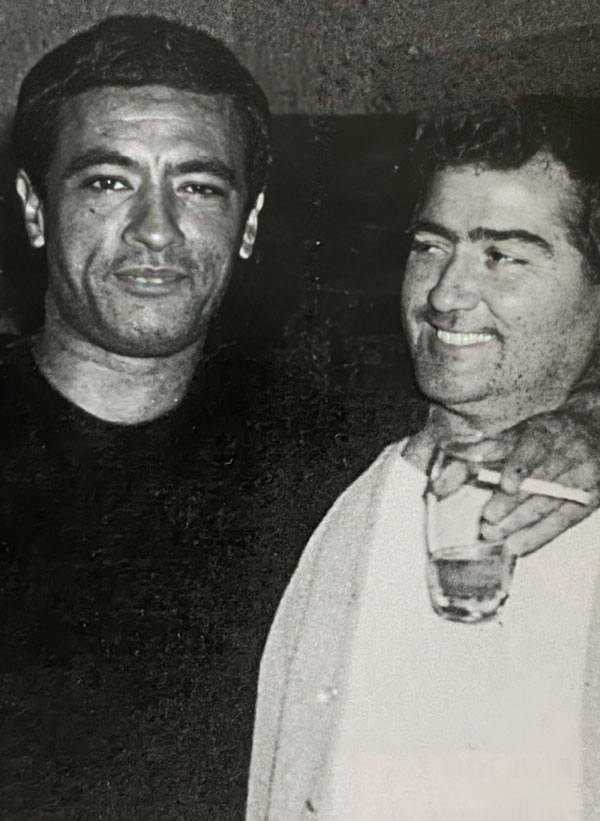

Lloyd (left), Pooch (right)

Stuff – Perry350

A small group of impatient soldiers and sailors broke rank and stormed into Ye Olde Barn, tipping the bodgies, widgies, and cowboys out into the street but they were outnumbered. Scuffles broke out. Police waited over the road. Across at the City Council carpark, the Airforce waited, vowing not to start anything unless something happens. They had been instructed not to do anything to disgrace the uniform.

Perhaps stirred by the intensity of the scene, fighting broke out among the bystanders, tying up police resources. At 8.30, the bodgies and cowboys set off from Ye Olde Barn and walked down Queen Street. At Civic Square, they were met head on by the servicemen. As the factions squared off, three bodgies broke off and ran across the Town Hall crossing but were chased and tackled. Police called for calm and urged onlookers to disperse. It is not known who threw the first punch, but a second later, it was all on.

Police and the airforce group mobilised quickly, moving between the groups trying to separate them, but were soon caught up in the melee themselves. Taking advantage of the mayhem, some bodgies shuffled through and carried on down to Curries Milk bar but found a group of navy conscripts barred the door refusing them entry. As it was their hangout, the rougher Vultures saw red and turned the tables. Sailors tumbled onto the street. Another group had marched back up Queen Street to Rendezvous Café closely followed by a contingent of servicemen. This fight blew out onto the street blocking the flow of traffic; drivers stopping to watch which blocked patrol cars.

Skirmishes quickly spread along the side streets. The Orange Hall, then the Polynesian Club in Pitt Street. The police worked tirelessly to stop the fighting, but the restless crowd following them vented their frustration by throwing firecrackers at them for spoiling the entertainment. It was all over by 10pm, with the bodgies having vamoosed leaving the police mopping up the dregs.

Despite the servicemen being the aggressors, the bodgies were blamed for the ruckus and the servicemen considered heroes. Ex-Kiwi, 24th Battalion wrote in the Herald’s ‘Letters to the Editor’ the following day.

‘It is high time some positive action was taken to stamp out this childish but dangerous cult. To condemn servicemen for their retaliation against the continued and studied insults of ‘Teddy Boys is rank injustice. Rather let us thank them for ridding our city, even for one night, of these uncontrolled, bird-brained louts.’

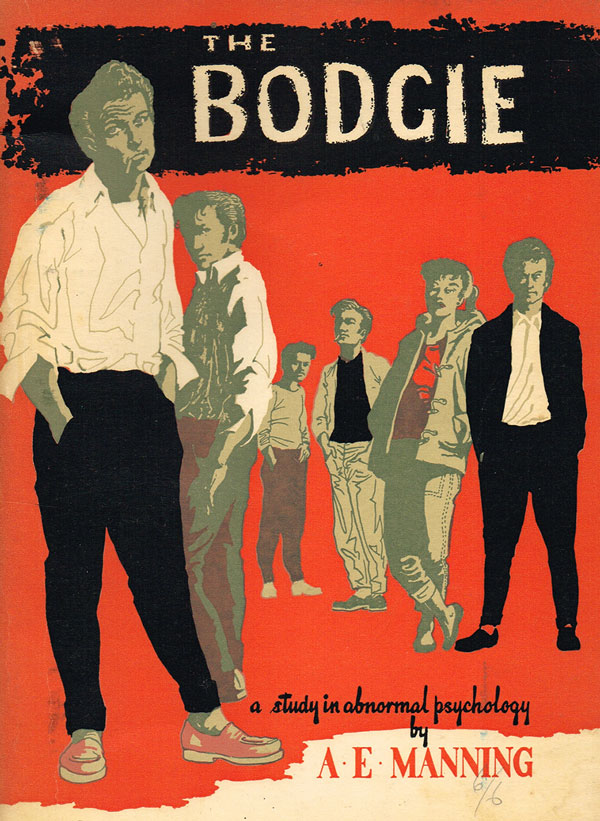

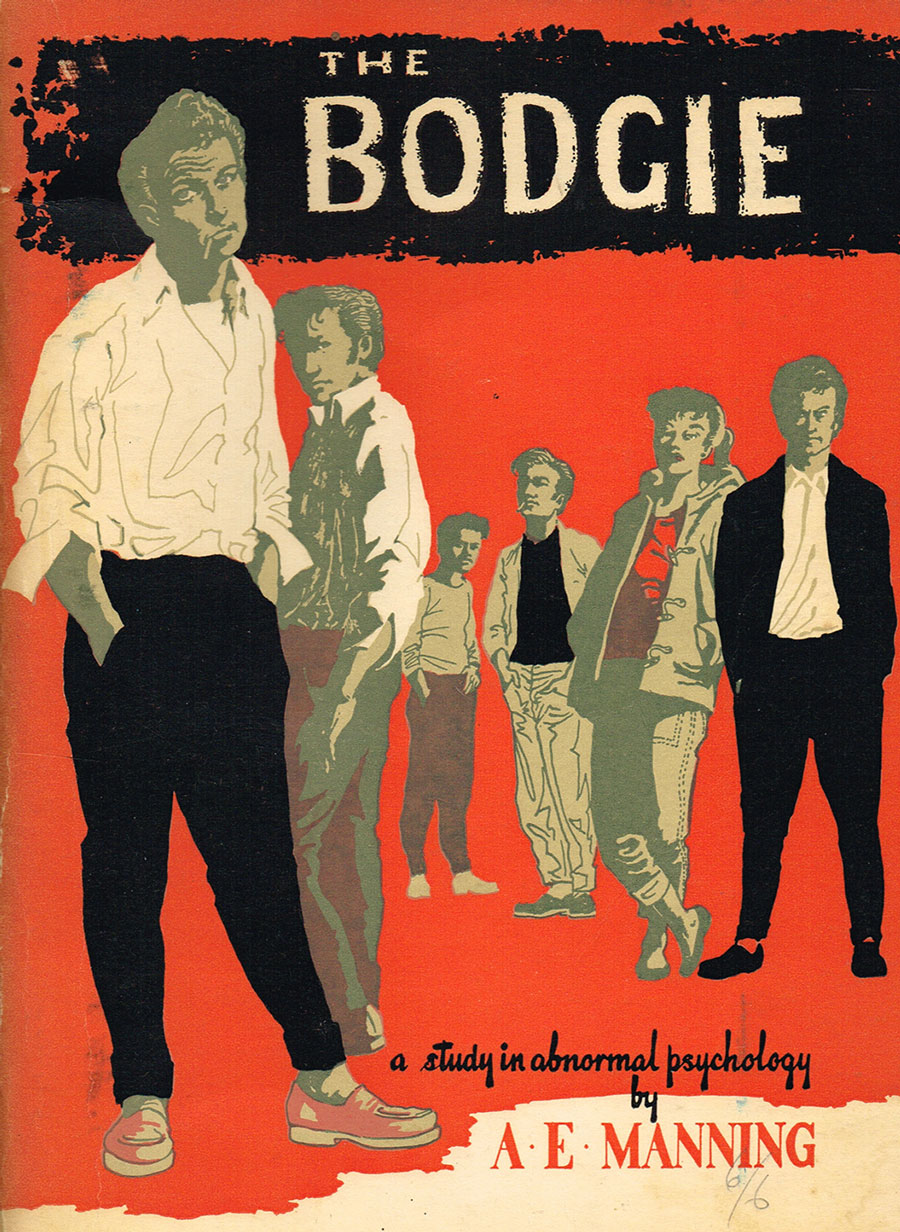

The Civic Square Riot was the first and last time the gangs united for such an event. One month later, Albert Black was hanged for the jukebox murder. Bodgies and milk bar cowboys continued to be an all-round menace and yet still fascinated. In 1958, Auckland Psychologist, Professor, A.E Manning authored The bodgie: a study in abnormal psychology was sympathetic but concluded them as juvenile delinquents.

By the 1960s, most of the gangs disbanded. Fearing he might land in further trouble, the alleged initiator of the march, Rainton Hastie, left for London on his OE. He found work in Paul Raymond’s Revuebar, a strip club, in Soho, inspiring a vision which would change his life. Within several years, Hastie returned and became a pioneer of the K-Road Strip Club scene.

Some members of the Vultures joined the early patched gangs which sprung up in the 1960s.

Herewini: “We drifted into jobs. Some stayed in Auckland and some left. You could say we grew up.” Despite being on opposite sides Pooch and Lloyd became close friends. “We had 6 o’clock closing, so I’d run into him at the beerhouses. There was never any animosity over the blues we used to have.” Yet both readily admitted they regularly fell out.

When Pooch agreed to contact Lloyd on my behalf, he rang back saying; “Ah, that silly bugger isn’t talking to me now. He doesn’t want to revisit those days.” When I contacted Lloyd directly a month later, he agreed to talk but was guarded.

In 2014, Herewini was well-respected in the Whangārei community as a naturopath and osteopath. He died in March 2016, one day after his old friend Pooch.