…

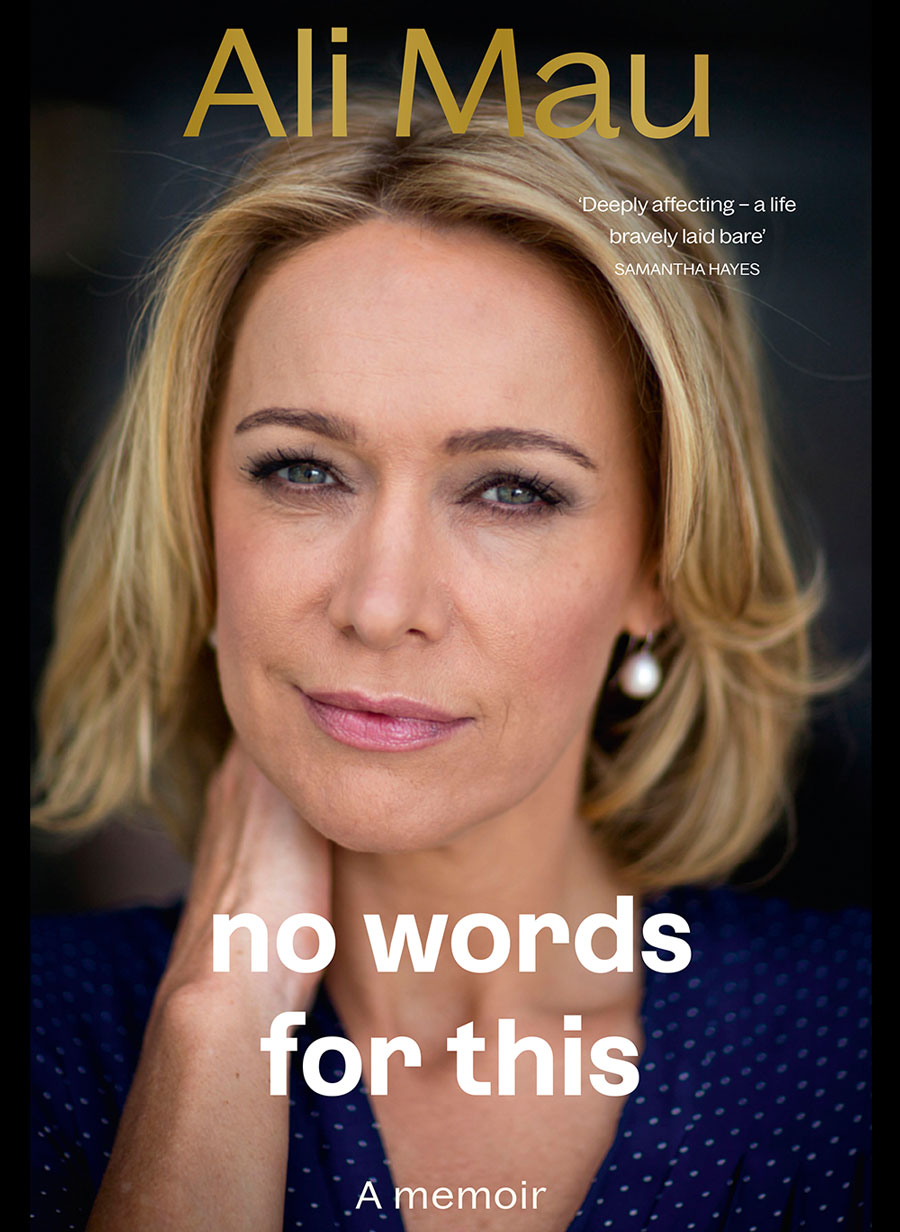

Mau, No Words for This.

In Conversation with Ali Mau

31st July 2025

Ali Mau has never been one to stay silent. In her searing new memoir No Words For This, the award-winning journalist, broadcaster and advocate lays bare a childhood marked by trauma — and the strength that emerged from it. In an unflinching conversation with Sarah Daniell, Mau opens up about the sex abuse revelations that redefined her purpose, the painful regret she carries over her colleague, the late Greg Boyed, sexism that still grips the media, and why the Gloriavale trial hits so close to home.SD: You’ve just turned 60. Grace Jones said in her memoir that “my age is the least interesting thing about me.” How do you feel about it?