BOOKS

War breaks out, Pātea, Taranaki

21st August, 2025

Ninety-five-year-old Waiheke novelist and adventurer, Margaret Mills, has had a rich life. She threw snowballs at Ed Hillary, danced in the streets on VJ day, raised four children, crewed on the Rainbow Warrior (and escaped from the bomb with minutes to spare), and sailed to Greenland. Her life has been buffeted by tragedy and lifted by romance. In an extract from Anecdotage, War Breaks out, Pātea, Taranaki, 1939.

In 1939 my mother left my father in search of romance. In hindsight I can understand that. My father was a very good man, much liked as a teacher but, like his father, he was very unambitious. He never aspired to the headmaster’s job. He liked Taihape and because it was wartime he was able to defer promotion and stay there. He was popular for the voluntary work he did in the community and the children loved him. Down to earth yes, but romantic, not at all. His greatest fault in her eyes was that he was a very bad dancer, but she knew that before she married him. He was born in 1901, she in 1909. Later she described herself as a shy little country girl who had married a very much older man. A country girl, yes, but shy? Never! Decades later she told me she married him to get out of Ōhura.

We went to stay in Pātea with my aunt Marge and her husband Sam. My father said I was to ask her all the questions I used to ask him about history, politics or general knowledge and I would get a straight answer. Taranaki in 1939 was very racist. It was just 70 years since the end of the Land Wars and most long-established families had family members who had taken part. I didn’t understand why Pākehā kids didn’t play with Māori kids and sat in different rows of desks at school, and why they got the strap for speaking their own language. Pātea and Taihape were about the same size but there the similarity ended. In Taihape we all sat together and played together at each other’s houses. Auntie Marge told me to try to keep quiet about the differences but unfortunately I didn’t. That was the beginning of my life as a misfit. I was just one step above the Māori in the pecking order.

The local hall doubled as a movie theatre and halfway down there was a rope across it. Behind the rope were rows of chairs for Pākehā of all ages and in front the Māori of all ages sat on backless forms. There were two barbers in town, one for Pākehā and one for Māori. Only in the local public hospital was there no separation. At primary school we had a history text book called Our Country. Its opening sentence began ‘Our country’s history began in 1840’… Later it referred to the New Zealand Wars of 1845 to 1872 as ‘putting down rebellious Māoris’.

One day, in the school holidays in 1939, Marge asked Mum if she wanted to go to a patriotic parade; this was in the opening days of WWII. Mum said that she wasn’t interested and I wouldn’t want to go either. Wrong, of course I wanted to go! She said she didn’t want me to go, that sort of thing wasn’t suitable for little girls.

Marge said it was ‘history in the making’ and I made things worse by saying that Pop had wanted me to go to that sort of thing if Auntie Marge said so. I was still grieving the separation between my parents.

I had to kick up a huge fuss before I could go. Marge said it was very important and I should never forget it. As soon as we got home she made sure I sat down and wrote to Pop to tell him all about it. I did this and he wrote back thanking her for taking me. No matter how small a town was it always had a brass band, a pipe band and a park with a band rotunda. On Sunday afternoons either of the bands would put on a concert. There wasn’t a lot in the way of entertainment in small town New Zealand before the war. This day was different. The shops were closed, the whole town was out on the street and the mood was jubilant. The parade was led by the brass band. Next came Boer War veterans looking stately in their shabby uniforms and riding on their immaculately groomed horses. The crowd cheered. The men threw their hats in the air. They were followed by returned soldiers from the Great War, some of them marching in uniform. More of them were on crutches limping along. Some had only one leg, some were missing an arm or an eye or were hideously scarred. The crowd cheered and the men threw their hats in the air. Next came most of the young men of the town all laughing and cheering and throwing their hats in the air while the crowd cheered. I noticed that some of the women were crying. The young volunteers were followed by the Boy Scouts and the Wolf Cubs. The Pipe Band brought up the rear.

Exhausted by cheering, the crowd broke up and wandered off. Excited by what I understood to be the most important day of my life so far, I asked my aunt why so many of the women were crying when everyone else was so happy. She explained that war was a men’s thing. The women were crying because so many of them had lost a father, a husband or a son to war and were likely to lose someone to this new conflict. Most young men, she said, are desperate to find adventure and believe that they are invulnerable. She also said she thought this new war might be even worse than the last one. Sam snorted and said that wasn’t possible.

When I asked Sam why he hadn’t marched with the other returned soldiers he said that he had seen war firsthand and it had taught him that it was a total waste of time and a total waste of too many young lives. I was not to tell anyone he had said that because it would get him in trouble with his job. He worked in the Post Office and civil servants were not permitted to voice unpatriotic sentiments.

My Aunt Marge had a habit of being right. I have never forgotten seeing this piece of history in the making nor have I forgotten what Uncle Sam said.

Margaret rides her first horse.

For a long time after the parade nothing much seemed to happen except that a lot of the town’s young men disappeared and came back for the odd weekend to strut around the town wearing khaki uniforms. They were at a place called ‘camp’ which Aunt Marge explained was at Waiouru. I knew where that was – it was near Mount Ruapehu. Aunt Marge and Uncle Sam laughed and laughed when I asked if they had gone there to ski. No, they were there to learn to be soldiers. Then they went to camp in Trentham which was near Wellington and then came back for final leave. There was another parade. The young soldiers strutted behind the band as they marched through the town in their stiff new ill-fitting uniforms proudly carrying their rifles. There was a general air of excitement. A lot of old men made boring speeches about our brave and gallant sons and a lot more women cried. Uncle Sam, who had been to the Great War, snorted and said ‘They’re cannon fodder. Heaven help them when they get to the trenches,’ Aunt Marge said, ‘Shut up, Sam’.

When we got home and were having tea they were discussing it and, as always, answered all my questions. They explained everything to me. Mum told them off and said I was far too young to have all this stuff put into my head. War and politics were for grown-ups and for men, and certainly not for little girls. I tried to shut her up by saying yet again that Pop had told me that if I had any questions about anything, especially about politics or anything at all, I was to ask my Auntie Marge because she had her head screwed on the right way. That made it worse because Marge and Sam laughed. A row started and Mum sent me to bed early for being cheeky to her. Not long after that we moved out and went to live in a shed. Then Mum got some men to come and look at where we were living. She cried and we moved into a state house. I missed Aunt Marge and often went to see her after school while Mum was at work.

Things changed slowly. The first big change in our lives came with rationing and the issue of ration cards. The basics of the standard New Zealand diet had its foundations stripped from it, meat, butter, sugar and tea. Meat was eaten at every meal. Butter was slathered on toast, hot scones and potatoes. How could we possibly manage now? The ration cards had to be presented to the butcher or the grocer. Groceries had always been measured out into paper bags. Plastic had yet to be invented and landfills were still called dumps. Very little went there, only stuff that couldn’t be composted or burnt. Poultry wasn’t considered to be meat and most backyards had a run. ‘Chickens’ were baby hens and we ate the adults which were called poultry. Similarly lambs were baby sheep and we ate hogget (a year-old sheep) or mutton. This, of course, was rationed. Fortunately Mum was a very good vegetable cook and her new boyfriend was a meat inspector at the freezing works so a few delicacies appeared on our table. I didn’t know Jim was her boyfriend. I did know he was her best friend’s husband.

The first time I met him was when we went to their place for Sunday dinner. It was a cold meal consisting of a rolled roast of beef, boiled potatoes and lettuce salad with condensed milk dressing (there was no other sort of salad or dressing in the New Zealand cuisine) and rice pudding. I don’t know when ‘rolled roast’ disappeared from our menus but not soon enough for me. It consisted of thin slices of prime beef layered with slices of fat. The whole thing was tightly rolled and held together with string and skewers then put in the oven and cooked until it was dark brown.

Meat fat made me sick. Glyn (an old boyfriend of Mum’s from her Ōhura days) had visited and taken us out for dinner. I ate roast pork for the first time. I probably pigged out on the crackling and the result was that I threw up in Glyn’s car on the way home. Mum was embarrassed and angry and Glyn told her not to fuss, it didn’t matter, I couldn’t help it. Then he lent me his nice big hankie. I decided that I loved him and I slept with that hankie under my pillow (after I had washed it, of course). From then on I carefully cut all the fat from my meat and put it on the side of my plate. Mum always cut most of the fat off the meat before she cooked it because she didn’t like it much either.

When we were at Jim’s for Sunday dinner he asked me what I thought I was doing cutting the fat off. I told him I had to cut it off because it made me sick. He ordered me to eat it and I tried again to tell him that it made me sick. He told me that when I was in his house I had to eat everything that was put on my plate. He added that I was an ugly, skinny, spoiled brat who needed a good hiding. I looked to Mum for help but she didn’t say a word and wouldn’t meet my eyes. When he stood up and put his hand on his belt I bolted for the door and cried all the way to Auntie Marge’s. It wasn’t a good beginning. I wonder if our relationship would have gotten off to a better start if I had eaten the fat and then thrown up all over him. You could get offal for your coupons, so kidney, liver, sweetbreads, heart and brains became a regular part of the diet. Sausages now had a lot more bread in them than pre-war. All our meat was sent to the Mother Country which most adults still called ‘home’ even if they had never been there or were third generation New Zealanders. Clothing was the next to be rationed as all our wool was going ‘home’. Then the wardens came round demanding all our aluminium pots to send ‘home’ to make Spitfires. Petrol was also rationed but very few workers had cars and it didn’t affect us. When I went to stay with Pop I went by train. He had sold the car when Mum left.

In 1941 when the Japanese entered the war, trenches had been dug under the macrocarpa hedges which were on three sides of the school grounds and we had air-raid drills two or three times a week. The kids were divided into groups of six according to where we lived, with the oldest in charge with the duty of shepherding the little ones home. If we heard an aircraft we were to jump into a ditch beside the road and we practised this regularly. The air raid drill had us running out of class and diving into the trenches.

Blackout curtains became compulsory and wardens walked around at night with their hooded torches. The smallest glint of light meant an instant fine. Blackout material was free. More and more black dresses were seen on the streets as the casualty lists in the daily paper grew longer. When the telegraph boy turned into a street collective breaths were held until he turned into a driveway. Then a huge feeling of relief was followed by pity and something almost like guilt. Cakes and casseroles were hastily prepared. The pink-covered which was published on Saturdays began carrying centrefold photographs of men who had been killed in action during the previous week but as the war rolled relentlessly on and on, more than the centrefold was needed.

Every Sunday morning from 8 am until 10 am greetings from the troops serving overseas were broadcast. Not everyone could afford a wireless (as radios were called then.) When a district was notified that their boys would be on, those who had a wireless borrowed large teapots and prepared for an avalanche of scones. You had to bring your own cup and butter or jam of course, but an increasing number of people had beehives and so there was plenty of honey. Marmite wasn’t rationed and was very good for you.

The calls were short and usually very similar and introduced by a frightfully English announcer reading out the caller’s name and rank. ‘Gidday Mum, Dad, Granny and Granddad. Charlie, here. Give Betty, Billy, Mary, Johnny and wee Annie a kiss from me. Is Annie walking yet? Give Buster a pat from me. How are you all? I am well and so is Peter. We are still lucky to be together. Thanks for the socks and cake and biscuits, Mum. I would love some more socks please because the issue socks are hard and too big. They give me blisters. I especially love getting your letters. Fancy Clem getting married! Where did he find a girl that would marry him? Probably some girl as ugly as he is. He’s too crippled to get called up and he gets better pay than we do, working in that office. I read your letters to pieces. Dad, how about writing to tell me about the farm and the footie? Peter and I are both in the team here and beat some Aussies easily, Good eh? I have to go now, Love to you all, don’t forget to give Buster his pat. Peter says “Hello”. Love to all from your son and brother, Charlie.’

Tears flowed freely. There was always the fear that this was the last time the beloved voice would be heard. On one terrible occasion the telegram came on Saturday morning and the wireless message came on Sunday morning, after the cakes and casseroles had been delivered to the bereaved.

Margaret’s father in the 1940s. A secret pacifist, he had to teach primary school-aged boys how to dismantle and clean guns. If he had revealed his opposition to war, Margaret says, he would have lost his job, even during the war-time teacher shortage.

Coal was now rationed. Clothes that weren’t on the rationed list became very hard to find. Old sheets and curtains became dresses and pillow cases. Flour came in cotton bags which, when the stiffening and the labels were washed out, were very fine cotton, perfect for making underclothes and baby clothes. Luckily Mum had learnt the necessary skills as a child on the farm, where money was always in short supply. Many women became experts at dyeing.

We kids had to play our part in the war effort, too. Paddocks with a boundary on a road were fenced by barbed wire or gorse hedges, both of which had sharp spikes which pulled wool out of any sheep that rubbed against them. We kids had to gather this wool and take it to school where we learnt to use a spindle to spin it. Then we knitted it into scarves or socks, depending on the knitter’s ability. We also learnt to make camouflage nets. A frame for this purpose was in every classroom and it took a very long time to make a net.

The worst job of all was picking ergot. This was fungus that grew on the grains of cocksfoot, a grass that grew plentifully along the roads and any waste spaces. It was slow and painstaking work best done by little fingers. The grains were small and we had to take a matchbox-ful to school on Monday mornings. Obviously this could spoil your weekend unless you were a very fast picker. Those who didn’t have a full matchbox had their names read out at assembly because they were letting our gallant soldiers down. What was it for? We were told it was processed into a substance that stopped bleeding and prevented infection. I have learnt recently that it is actually a hallucinogen and an abortifacient. I also learnt that the government was paying for the stuff. You have to ask who got that money? What did the government actually want it for?

I learnt about men called profiteers. They were wicked men who had somehow managed to avoid being called up and who made money from the war. There was something called the ‘black market’. On the black market you could buy stuff that was rationed, especially petrol, but all sorts of other stuff as well. Of course, black market goods were very expensive, often twice the price you would pay if they were legal. Nearly everybody in town knew who the black marketeers were, probably even the police, but they were never arrested. Nobody would dob them in because you never knew when you might need them. Sometimes practicality has to rule over conscience.

Uncle Mick was training to be a pilot at Bell Block, an airfield near New Plymouth. He was having trouble with his maths. And Pop was coaching him. When Mick could get weekend leave he would come to stay with Marge, and Pop would come from Taihape and stay there too. I loved the Sunday dinners listening to the type of conversation that I never heard anywhere else. Mum wasn’t there. By now she and Marge were not speaking. Mum said Marge should be loyal to her and not have anything to do with Pop. Marge disapproved of Mum having an affair with a married man, so they had become estranged. And we know where Mum went for Sunday dinner.

No one ever told Mum that Pop and I sometimes went to Ōhura and stayed on the farm. The conversation there was good, too, especially when Mick (who had finally mastered maths) was there on final leave before being shipped to Canada for further training. He was 27, a ripe old age for a fighter pilot when most of them were only 19. Mick’s nickname was ‘Grandpa.’

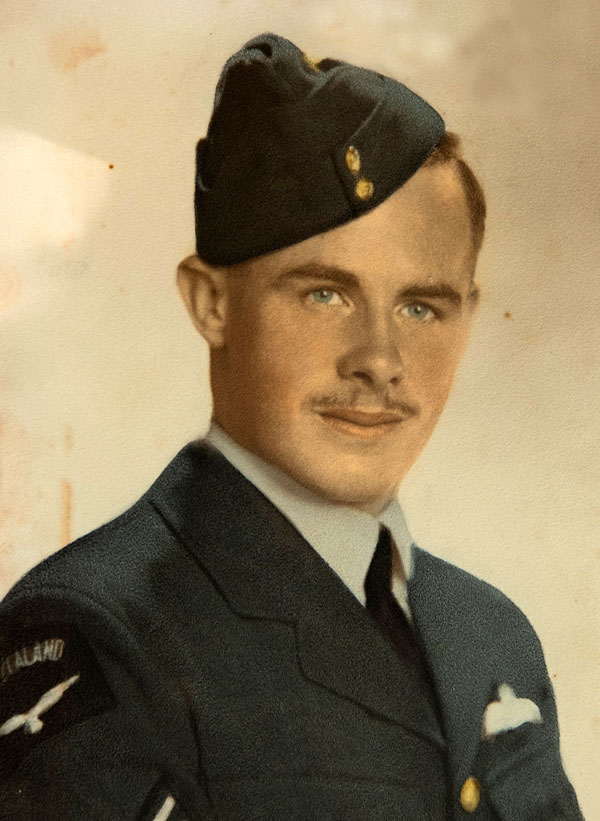

Uncle Mick photographed early in the warm before he was an officer. By 25, he was a Spitfire pilot. His nickname was ‘Grandpa’, because the average age of those killed was 22. Just 24 percent of Allied pilots survived the war unscathed. One of them was Uncle Mick.

By now households were expected to donate sheets for bandages. The teachers tore them into strips and we girls had to roll those strips up. When we had a roll of a certain diameter we had to tie it up with string so that it couldn’t unroll. I didn’t know what the boys were doing while we exercised our female skills until Pop was over for a weekend and told me that the younger ones were taught marching and those in standard six (our last year at primary school) were taught to take a rifle to bits, clean it and put it back together again. When they got to high school they would go into the school cadets and learn more military skills. When I asked him when the war would be over, he sighed and said that when this one finished there would be other wars unless humanity came to its senses. And then he said ‘Don’t tell anyone that I said that.’ I answered, ‘Auntie Marge says the same thing.’ He sighed again more deeply.

Years later I learnt that Pop had met Marge before he met Mum and it had progressed to the point where she invited him home for Sunday dinner. My grandparents liked him very much but the younger, prettier sister moved in and captivated him. Decades later I asked Mum why she had married him when she said she had never loved him. She said he was quite good-looking, he dressed well and had a good job — and she desperately wanted to get out of Ōhura.

Pop never stopped loving her and didn’t really give up on her until his sister got a private detective on the job and told him about the boyfriend. Their marriage had lasted for nine and a half years.

An extract from Anecdotage, War Breaks out, Pātea, Taranaki, 1939.

Anecdotage, by Margaret Mills, $39.95, pub Pukerakau Press, incproductions.co.nz