ARCHIVE HIGHLIGHT

Coming Home – The Story of Life After Near Death On a Mountainside

In April 1986, Felicity Price’s cover story for North & South magazine is an epic tale of adventure and survival in the most harrowing circumstances with the most dire consequences.

23th October 2025

Photo: Mike Perry

PHIL DOOLE shudders with exhaustion and turmoil. Sweat dribbles from his brow into his eyes. He peers anxiously up at Mount Cook’s awesome eastern face and bends to the challenge. He swings his foot firmly and surely, into the next icy footprint in front of him.

HE AND three friends are on the Linda Glacier, one of a dozen or more climbing parties aiming for the top of this much-prized peak, this past summer.

DOOLE’S STRUGGLE, though, is on a different plane – far removed from the natural hazards, and inherent fears of the mountain climber. He has no legs. They were amputated just below the knee on Christmas Eve three years ago, after he spent 14 days trapped on this same mountainside.

HE’S BACK, making his third attempt to climb it. But it’s not going well. His movement is cumbersome, not the natural, fluent action of a tall, leggy mountaineer. That’s all just a memory. Plastic legs just won’t work like real ones. He’s getting agitated, annoyed with the mountain again, and himself. He wants so much to get up there, finally, but he feels it slipping away.

Most summertime ascents of Mount Cook start just after midnight. The climb takes 10 to 12 hours. The early start means that climbers reach the summit well before noon, when the summer sun melts the ice and snow, and climbing becomes difficult and icefalls are more likely.

Climbers, Mark Inglis, left, and Phil Doole. Photo: Lloyd Park

GOING BACK

HE PLANTS his ski poles in the snow, balances on them, and slowly, carefully follows the footsteps of his mate. Brian Weedon, of Christchurch, has scaled peaks overseas with an Englishman who lost both legs, and Doole sees no reason why he can’t keep climbing with his plastic limbs too. Weedon is himself following in the tracks of another climbing party who took the Linda route up Mount Cook earlier in the day. Following is much easier for Doole’s team. They don’t have to pack down the deep snow with each step, or waste time going up blind alleys in the maze of crevasses that criss-cross Linda.

Doole has the right people to help him get to the top, but is the time right? He knows the others have to be back at work on Monday, and he knows he’s holding them up. His concentration is necessarily intense as he measures the centimetres. His eyes bore into the snow where the next step will be, while his plastic feet make each step safe. His hands grip the ski poles, which are frustratingly long now that the terrain is steep. Every now and then, he has to let a pole go and haul his ice axe off his pack to secure the next step. The poles are necessary but they’re also a damned nuisance. And it’s so slow.

Is this his climb? He’s got to think of the other three. Two of them have never conquered Cook before. He can’t expect them to wait for him all the time. But the cool of the evening helps him keep going. With nightfall, the four make a bivouac in the snow, 3000 metres up Mount Cook. It’s not the highest Doole has been … Middle Peak Hotel, where he spent an icy fortnight three years back, was less than a thousand metres further up. Doole is back to better that. He sleeps on it though and by dawn he’s decided to stay put. Let the others go for the top. Today’s not the day to come to terms with this mountain. Phil Doole will still have unfinished business with Mount Cook … until next summer at least. For the third time, the summit has eluded him.

The other three leave at 6.30am and promise to “be back in a jiff’ – a quick up and down and they’ll be off down to Plateau again. But Doole has to wait eight hours for them. He watches them go… and for a while it’s nice, lying there having a rest, while they grunt in the sun, sweating, struggling their way up. For a while, Doole just enjoys being there, at peace, in the place he loves. It really feels good. In a way, it’s even better than coming home.

But time passes, and he can hear the others yahooing around on the top. They’ve made it, and they revel in it for a long, long time. As he dozes beside the bivvy, Doole’s dream loses the idyll. He’s starting to get pissed off… he’s angry that his mates are making such a mammoth expedition out of it, and he’s beginning to realise that he just might have made it too, given all this time.

He goes over in his mind how it could be done. Next time he’ll get retractable ski poles to make it easier, or a ski pole/ice axe combined to make it safer. He’s a mulish man, stroppy, cocky, and sometimes arrogant. But he’s got guts. He refuses to admit that deep down there is a searing, pointless anger at not making it. He swallows hard on the frustration that his friends made it, while he sat around and was forced to watch and listen to their joy… Instead he strokes and chides his ego: There’s no rush… There’s always next time… next summer. He’s going to climb this bitch of a mountain if it kills him.

Back down at Plateau Hut the next day the weather closes in. Doole and one of his friends decide to wait for it to clear, so they can fly out. The other two decide to ‘walk’ out.

INSIDE THE hut, it’s warm, friendly, a fine place to be. Doole feels at home again. He’s surrounded by climbers from New Zealand and all over the world, and it’s good to be one of them again. He’s happy. Three snowbound days later, it’s still coming down. Doole has thoroughly enjoyed himself but he and his friend decide they’d better walk out, or they’ll never get back to work. It’s a steep drop over the side from Plateau down to the Tasman Glacier below and a long haul back to base. Doole isn’t at all sure he can do it, but he does. After 10 hours of concentration and physical strain that takes him close to exhaustion he makes it to the end of the road where friends have left his car. He is ebullient, proud – another tough goal achieved, like walking the Milford Track over Christmas, six weeks back. He’d determined that he would finish it – and he did.

After the disappointment of not reaching the summit he can salvage something from this trip. He has managed the toughest bit of climbing he’s done since ‘the accident’ three summers ago.

NOVEMBER 15, 1982

DOOLE AND Mark Inglis, both members of the Mount Cook National Park mountain rescue team, start out on an early season training climb up the east ridge of Mount Cook, New Zealand’s highest mountain.

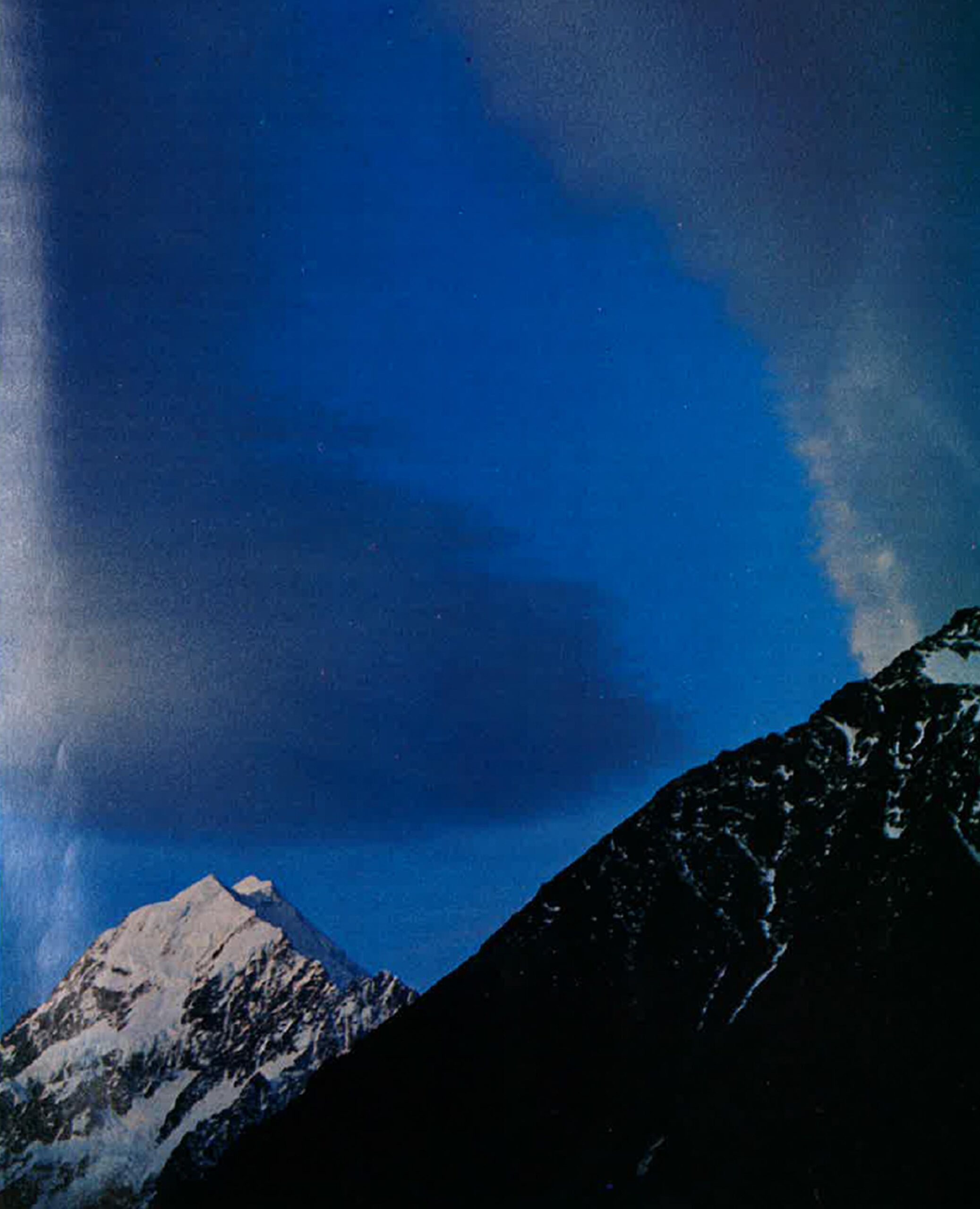

Called Aoraki, “the cloud piercer”, by Kāi Tahu, it is a moody mountain, isolated, dominating the South Island Main Divide and providing a constant challenge for mountaineers from all over the world. On a good day, Aoraki’s west side is smooth ice and snow; the east, jagged rocks and cliffs of ice stab the skyline.

Most summertime ascents of Aoraki start just after midnight, under moonlight. The climb usually takes 10 to 12 hours. The early start means that climbers reach the summit well before noon, before the summer sun melts the ice and snow, making climbing difficult, and icefalls are more likely.

Dawn comes at four, and they are off just after five. It is a long, slow climb. For both, it is the first climb of the season and takes some getting used to. “I suppose we should have tried something a bit easier and shorter for our first ascent,” says Doole, with hindsight.

As they inch their way up the East Ridge, they see the thick bank of grey-white clouds warning of nasty weather. They stop a couple of times to talk about it, but decide to keep going: “We were feeling good and had plenty of confidence,” says Doole. “We could see the front coming in, but we thought it would be a day or so before it arrived. Reaching the top of the ridge at 6pm, the force of the wind comes as a shock. No longer sheltered in the lee of the mountain, for the first time that day they are exposed to the full force of the wind, and they can’t hear each other shout above the roar. They start climbing down the other side.

Inglis: “Jeez it was cold, and when wind blows that hard, it takes on a personality all of its own.”

When Phil sees a schrund in front of him, it is too hard to resist. He goes in to get away from the relentless, pounding wind and Mark follows him. It is a haven, and it is tempting to stay. They discuss it: “We were pretty stuffed,” says Doole. “And once we got into the tunnel and out of the wind, it seemed pretty safe. We had a psychological barrier about going out in the wind again. It was silly really, we should have kept going.”

Outside, the sky darkens, the mountain becomes cold and threatening. Sleek, lenticular clouds indicate jetstream winds that lick the mountain’s contours at speeds over 100 kilometres an hour. Under such an onslaught, the pair dig deep into their tiny ice cave. They will remain there for two weeks.

They are unprepared for anything more than a couple of nights on the mountain. But they know all about snow survival. They are wearing typical cold-weather climbing clothes. Inglis has a layer of wool next to his skin, a cotton shirt, pile jacket, and a shell of Goretex, Doole has a few more layers of wool, and a duvet jacket.

Dawn the next day is much the same, howling gales lash the mountain. Inglis’s feet feel numb; he knows he is getting frostbite. He tries massaging his legs lightly and elevates his feet, but that is all he can do. Anything more energetic will sap his dwindling strength.

Normally, the winds wane at dawn. But these gales are so fierce they won’t let anyone move in the mountains for days. A series of westerly fronts are moving in from the Tasman and across the South Island. The first two fronts are so close together, there’s no calm between.

Along the Main Divide, the westerly storm clouds gather, dumping sleet and two metres of snow. The wind gusts to 80 knots blowing the wind recorder off the Tasman Saddle. In the next few days, it will reach over 100 knots.

THE DAYS tick by and tempers fray. Local medical expert Dr Dick Price is consulted: How long can they last up there without food? He puts a 10-day time limit on their survival.

No-one knows for sure where the two stranded climbers are, but the park staff know the mountain well, and they guess correctly — the schrund formed by the east ridge meeting the summit ridge, 300 metres below the middle of Cook’s three peaks.

Rescue operations for the two lost climbers are based at Mount Cook National Park headquarters – a big, woodstained, alpine-framed building in the centre of Mount Cook village. For two weeks, it became a news centre of New Zealand, with a steadily growing group of reporters, clamouring for information.

The fifth day on the mountain is probably the worst. The climbers realise they haven’t the strength to make it down, and they know they might be here for many more days. The schrund is 10 metres long, and narrow. Their shelter is not much bigger than a single bed. They have made a shelf to lie on, and have blocked up some of the gaps. They wish they had shored up snow over the end of the schrund, to stop the wind and spindrift blowing through. But it is too late now. They haven’t the energy.

On the evening of the eighth day, around seven, the wind subsides a little. Helicopter pilot Ron Small is able to fly up to the summit of Aoraki for the first time passing the schrund. Phil wakes from a dream and leaps out, waving frantically as the helicopter flies away. But one of the rescue team on board sees the tiny dot in the snow. They return but the strong updraught makes it impossible to hover. Ron tries to work out how to ride the draught, a bit like going up in a speeding elevator. On the way up past the schrund, Digger Joyce throws out a drop-bag, containing rations and warm gear. It teeters on the edge, and plunges down the mountain side. They return to the village for three more dropbags, and try again: Ron rides the up draught past the schrund, putting just enough bite on his blades to prevent them windmilling past the safety limit, the engine barely idling. They do it three times – each bag landing right on target, and one even falling on Phil. The bags are packed with radio transmitters, food, sleeping bags, and a vital gas burner.

“We were like kids at Christmas,” says Inglis. “We opened up the bags like they were presents.” An hour later, the radio base at rescue headquarters crackled into action: “This is Middle Peak Hotel… ” The schrund is named, and the whole country learns that the pair are alive and well, if not kicking.

RADIO CONTACT is made several times over 24 hours and the batteries, struggling to cope with sub-zero temperatures, give out. “I think there was a lot of pressure on the rescue people to find out as much as they could, for our relatives and the media,” says Doole. The media file reports that Search and Rescue fear for the climbers’ safety when radio contact is lost. They seize on straws for stories. For six days, there is silence from Middle Peak, and papers have to print something.

In the village, rescue operations are run by Chief Ranger Bert Youngman. His deputy, Martin Heine, in charge for the first eight days, remembers the mounting tension, the total absorption in the situation.

He recalls the joy at locating the climbers, “There was an incredible feeling of elation, but it was tinged with worry, because then we had the problem of what can we do now?”

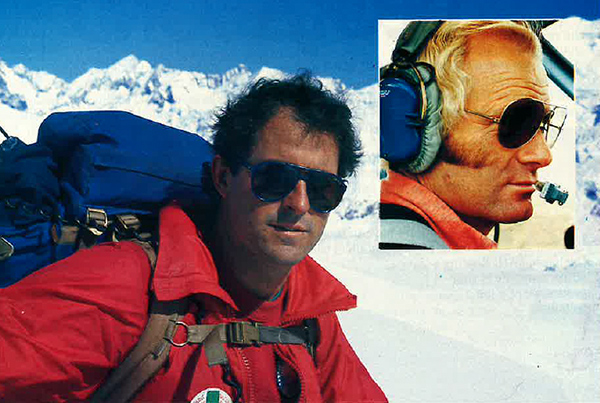

Helicopter pilot Ron Small is in the midst of what he will later describe as “the loneliest two weeks of my life”. He is known throughout the region as the best rescue helicopter pilot available. This is his 50th rescue in seven years, half of them off Aoraki. He has been flying for 14 years – seven in helicopters, normally dropping heliskiers and skitourers high in the mountains, landing in snow 10 or 20 times a day. For his part in this and other rescues Small will later be awarded an MBE. But right now, waiting for the weather to clear, he is under tremendous pressure: “I’ve never been involved in a rescue operation that took so long or involved so much pressure. I was beginning to doubt if I was being too conservative in my decisions as to whether or not a rescue was possible.” Small logged up no more than 10-and-a-half hours flying time throughout the rescue operation, but he was on standby from day light to dark for 14 days. For all that time, he was pestered by the large news team in the village. He says he “squirmed with embarrassment”.

THREE THOUSAND metres above, Inglis and Doole are beginning to feel pretty low. They haven’t talked much all week, to conserve energy.

Prolonged exposure to the cold has made them exhausted. Their diet of biscuits, chocolate, raisins and barley sugar is only just keeping them going. Both have frostbitten feet and they have enough experience in the mountains to know exactly what that means. Slowly, their toes are dying. And the longer it goes on, the further the frostbite travels up the foot towards the ankle. Apart from initial pain, the frostbite doesn’t hurt. Their feet are numb. If they dare look, they will see they are white and hard. Although Inglis has taken off his boots he has not taken off his socks. Doole, on doctor’s advice over the R.T. removes his boots, knowing as he does that he won’t be able to get them on again. He is now helpless, unable to move further than just outside the cave and totally dependent on helicopter rescue.

Both men realise they are in danger of losing their toes. That doesn’t worry them. They don’t know they will lose their feet as well. But frostbite is not preoccupying their thoughts. What they are worried about is life and death; are they ever going to get out of this hell-hole alive? Most of the time, they are optimistic. They have complete faith in the mountain Search and Rescue system – of which they are part. But now, after days with no contact and no let-up in the wind, they start to have doubts.

This mountain, after all, has claimed many lives. Aoraki was first climbed on Christmas Day, 1894. Since then, around 850 men and women have scaled its peaks and 40 have died. Park rangers say that’s not a bad average for such a popular peak, hardly a killer mountain compared with some.

The highest mountain in Australasia, Aoraki lures climbers from all over the world. The Park’s log book is as full of foreign names – from Japan, Europe and America – as it is with New Zealanders. It is regarded by many as the cream of climbing in the Pacific, drawing the same climbers back again and again.

Search and Rescue at Mount Cook is run by professional mountaineers – men like Inglis and Doole, who form a 12-man summer rescue team. Doole is one of six seasonal workers just taken on to help out over the summer climbing season. He has only been there a fortnight, and this is ironically his first climb as a rescue team member.

MARK INGLIS

INGLIS IS HIS team leader, and this is their first climb together as well as the first of the season. Ingis is on the permanent, year-round staff at the park – employed, like all other park staff, by the Lands and Survey Department. Both are experienced mountaineers. Inglis has climbed Aoraki several times. Climbing has been his passion since he was a boy.

Mark Inglis has a lot to live for as he sits in his icy prison waiting to be rescued. He and his young wife, Anne, have a baby daughter Lucy, aged 10 months. He has a happy home life, likes his job, and enjoys life at Mount Cook. The son of the Strathallan County grader driver, he grew up and went to school in the friendly farming town of Geraldine. He left school to work on a local farm for a year, then moved to Christchurch, where he was accepted for a three-year Park Rangers’ course at Lincoln College. Disillusioned with what he felt was an administrative emphasis in the course, Mark dropped out after a year. Although short and slight, he has always been a keen climber and skier, and decided to return to his old haunts – to drive his ice pick into the mountainside, instead of reading about others doing it.

He got a job as one of the mountaineers at Aoraki and before long was promoted to rescue team leader, ski patrolling on the Tasman Glacier – and doing mountain rescues. The rest of the time, he worked on the park’s 17 climbing huts – around the village keeping the Park lands trim, and looking after track and bridge maintenance on the region’s many tourist walks.

While he was living in the village, he met Anne, a housemaid at the luxurious THC Hermitage Hotel. They married, settled down in their low-rental Park Board house and started a family. Mark spent some of his spare time climbing, and skiing. Anne, neither a climber nor a skier, stayed in the village with baby Lucy.

PHIL DOOLE

TALL, SANDY haired, Phil Doole is two years older than Mark and comes from quite a different background. He grew up in the city – Wellington mostly, where he went to St Pat’s College, followed by a year at Victoria University. Accepted for surveying school at Otago University the following year, Phil shifted away from his family, to Dunedin. After completing a surveying degree in 1978, he got a job with the Forest Service aiming to become a registered surveyor. His plans were postponed for six months though, when he fell down a crevasse and broke his leg while climbing the Linda Glacier route of Aoraki.

Phil and a companion had just abandoned their attempt on Aoraki and were climbing down the Linda when they encountered two other climbers who had been hit by an avalanche. One was dead, and the other was in bad shape. Phil was pretty upset: “It was an ice avalanche, and the guy was badly knocked about. I think our minds weren’t really 100 per cent on what we were doing after that.”

On the way down the mountain to get help, the pair slipped into a crevasse. Phil’s companion managed to climb out – and in a whiteout made it to the Plateau Hut where he radioed for help. The helicopters came in the next day when the weather cleared, but it was too late for the injured climber, who had died overnight. Phil was rescued from the crevasse and taken to Timaru Hospital with a badly broken leg.

He was in hospital for 99 days – followed by three months of intensive physiotherapy before he could go back to work with the Forest Service.

Based on the West Coast, he joined the face rescue team, did a lot of tramping and climbing, learned to fly, and generally had a good time. He was not at all pleased when the Forest Service transferred him to Rotorua. The move meant he could get his surveyor’s ticket, but it also meant losing his girlfriend and leaving a lot of friends behind. He stuck it out for six months – became a registered surveyor, and then a staff surveyor – but he was forever hankering to get back to the mountains and the people he loved.

When he realised a transfer south wasn’t forthcoming, he resigned and took a job for the summer at Mount Cook. He moved into an old Ministry of Works house in Desolation Row in the most popular part of the village – away from the Hermitage and the park headquarters on the shingle fan and started to enjoy himself. It seemed a single man’s paradise, the summer promised to be exciting.

The rescuers: mountaineer Don Bogie, left, and helicopter pilot Ron Small (inset).

RESCUE

DOWN IN the village on the 13th night, there is an interdenominational church service at the Park headquarters to pray for a speedy rescue. Two hours later, the thick cloud that has been hanging over the village all day lifts and the western slopes of Aoraki are visible at last, burning bright orange in the setting sun. Hopes are high. THC shouts the rescue team a late meal in the Hermitage, and pent-up tension is temporarily relieved in manic merriment.

The weather forecaster is up at 3.30am as usual the next day – to be greeted by thick cloud.

By 7.30am the cloud cover is a little higher and the decision is made to go for it. Ron Small and Bill Black, both flying Squirrels, head up Tasman River towards Lake Pukaki to find a gap in the clouds. They climb up and break through to see Aoraki sparkling in the sunlight. Down in the village, straining ears can hear the distant sound of choppers overhead and they know the rescue is on. A radio is dropped onto the schrund, and soon Doole’s voice comes through loud and clear. He can be lifted off in his harness, but Inglis is not so good, and will need a stretcher. As well as frostbite, Inglis has developed a chest infection from prolonged exposure.

Small flies down to the Empress Ice Shelf where mountaineer Don Bogie attaches himself to the strop underneath the chopper. Within minutes, Bogie finds himself dangling above Middle Peak Hotel. With six ascents of Aoraki to his credit, Bogie knows it well. He’s been stuck for two days near the summit himself in a big storm. He knows the schrund and he knows the two men trapped inside – he has climbed with Inglis, and Bogie’s first day at work at Aoraki saw him rescuing Phil Doole off the Linda Glacier.