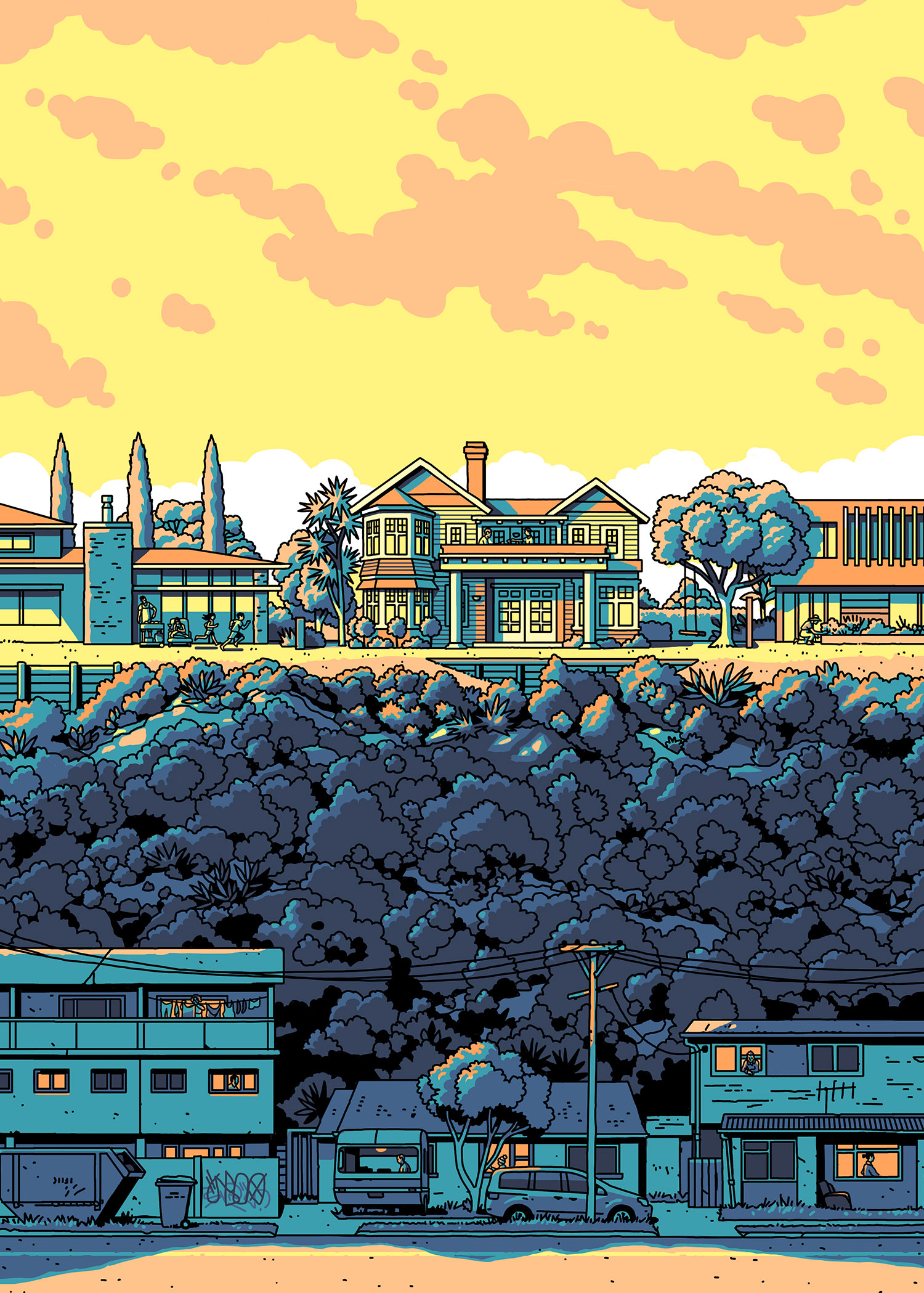

The Great Divide

Illustration: Ross Murray

In a single generation New Zealand has transformed itself from a home-owning democracy into a society fractured by property wealth — between those who have it, and those who do not. How did it happen and what is it doing to us?

By Rebecca Macfie

The year was 1988. New Zealand and all of its domain was newly and proudly nuclear-free. The prime minister, David Lange, had recently fallen out with his finance minister, Roger Douglas, after calling for a cup of tea. We were entranced by a new home-grown TV show called Gloss, about rich and glamorous people in Auckland. The sharemarket had crashed the previous October from a spectacular height, and once-glittering corporations were being revealed as mere houses of cards.

We worried a great deal about the cost of mortgages, even though interest rates were down to below 18 per cent. But — and this might seem incomprehensible from the vantage point of 2021 — social gatherings were not dominated by talk about houses. There were generally enough of them to go around, at a reasonable price.

That is not misty-eyed romanticism. For verification, consider the words of the National Housing Commission in a 1988 report: “New Zealand does not have the huge, insoluble problems of homelessness and substandard housing which confront many other nations.”

The commission was one cog in a sophisticated housing system that had built up over the 50 years since Michael Joseph Savage carried a dining table through the front door of New Zealand’s first state house in 1937. That system had been tweaked and refined through the post-war decades, but it was underpinned by a broad consensus that it was good for social wellbeing if families owned their homes, and that they should be supported by the government to do so where necessary. For those who couldn’t afford to own, there would be state houses at subsidised rent.

It was the job of the commission to produce a detailed report every five years to keep the nation informed. As it turned out, the 1988 volume was its last: In a sign of the reforming times, it was in the process of being disbanded. Its final report noted rising stresses. There were families in South Auckland crowding into garages and relatives’ houses while they waited months for a state house. Some 17,500 households were in serious need, made worse by increasing unemployment due to radical economic restructuring. Private rents were rising, and Māori and Pasifika people faced widespread discrimination from landlords.

But there was much that was working well. Almost three-quarters of the population owned their homes, and 10,000 modest-income households a year were being financed to do so through government mortgages. Around 7000 new families a year found security and shelter in a state house. It was a rare and shocking sight to see a homeless person sleeping on the street.

The commission reminded the nation not to take this for granted. “In Great Britain there are large numbers of people living permanently in bed and breakfast establishments at public expense because of a shortage of more permanent affordable accommodation. In the United States night shelters can only admit a small proportion of those who wish to use them and the remainder must sleep rough. In both countries and in much of Europe, ‘handbag people’ abound in the streets of the cities. In all of these countries homelessness is part of a cycle of poverty very difficult to climb out of.”

Fortunately for New Zealand, “the legacy of our forebears in providing a relatively adequate housing stock gives us a better basis than in many countries in meeting these (consequently more limited) problems,” the commission noted. “[T]here are indications that adequate housing for all and the abhorrence of extremes of poverty remain central ideals of most New Zealanders.”

Within a few short years that legacy had been smashed.

We New Zealanders, who once abhorred poverty, now step around people sleeping in shop doorways on Queen Street, Courteney Place and Colombo Street, and are no longer shocked.

Within a generation New Zealand’s home-owning democracy has been transformed into a class society divided by property wealth. Those who have it effortlessly accrue more of it, and can transfer the benefits of it to their offspring. Those shut out from it are condemned by income, age, race and circumstance to pay a large proportion of their wages to property investors for somewhere to live.

We New Zealanders, who once abhorred poverty, now step around people sleeping in shop doorways on Queen Street, Courteney Place and Colombo Street, and are no longer shocked.

A time bomb of poverty among the elderly is coming down the line, as increasing numbers of people reach retirement without their own homes. Māori, excluded from their ancestral lands by war and theft, are being locked out from housing wealth: their rate of home ownership has plunged from over half in the 1980s to less than a third.

It is a catastrophe, but it is not an accident. It has been coming for three decades, and it is the product of deliberate choices.

Deep-rooted change can be hard to diagnose in the moment. It might be easy to see consequences — more people living on the street, more children without shoes and school lunches, more babies with avoidable third-world diseases turning up at ED. But identifying the mechanics needs decades of data.

When it comes to the tectonic shift in New Zealand’s housing system, we’re starting to get that data now. One of those forensically analysing it is researcher Kay Saville-Smith, a leading figure in the Building Better Homes Towns and Cities national science challenge. So stark was the picture unveiled in her latest study that even she, after three decades in the housing field, was so startled that she thought she may have made a mistake. But she hadn’t. Since the late 1980s, investors have increased the number of houses they own by 191 per cent, and owner-occupiers by only 37 per cent. Housing in New Zealand is no longer about homes, dignity and security. It is a financial commodity.

Poor households now commonly spend over half their incomes just keeping a roof over their heads. Over 40 per cent of our children live in rented houses, denied the stability they need to thrive. The population of people severely deprived of adequate housing is over 100,000 — bigger than the city of Whangarei.

Commentators routinely point the finger of blame for our housing crisis at hidebound councils, a rigid Resource Management Act, an inefficient construction sector and profligate millenials. There is truth in some of these things, but none explain how we have become a society cleaved by property wealth and the lack of it. Given that half of all adults own the home they live in and half do not, and that the wealth of those who own houses and land grew by $400 billion in the decade to 2019, surely we need to shift our gaze to the question of who holds all that wealth, and who is paying the price for it.

When Kay Saville-Smith arrived as a young sociologist and historian to work on policy at the Housing Corporation of New Zealand in 1988, she found it a vibrant, innovative place. She’d spent time in Hong Kong, at Massey University as a lecturer, and at Parliament as an advisor to Labour MP Fran Wilde. At HCNZ the work was challenging and concrete — literally — and anchored in the real needs of people. “ I just fell in love with it in a way,” she recalls.

“It was building houses, designing houses, working out who needed what where. You literally could drive around and see where the corporation was — sometimes for bad, where it had not done a great job — but you could see in the built environment the unfolding of housing policy since the 1930s. Sometimes the housing was absolutely at the cutting edge of good practice and good design for the period.”

The HCNZ was one of the biggest organisations in the country. It carried the kaupapa of Savage and the post-war consensus: it ran its own treasury operation which, in the late 1970s, accounted for 38 per cent of the New Zealand mortgage market through loans to low-income families. It issued affordable loans to modest households for essential repairs, and financed councils and welfare groups to build pensioner housing. On top of this, the Department of Māori Affairs issued hundreds of mortgages a year to Māori home buyers.

From the late 1950s until 1986, families were also able to capitalise the family benefit, a universal payment for each child. This meant that the future value of the benefit could be paid in advance towards a deposit on a first home. For families with no savings and low wages, it was the door to housing security.

By the time Saville-Smith joined the HCNZ, it had assets worth $6 billion, the bulk of which was state houses. Rents for these homes was fixed at no more than 25 per cent of the tenant’s income.

Over the decades there had been governments (mostly National) with a penchant for selling state houses, and governments (mostly Labour) with a penchant for building them. But over time the portfolio grew, and by 1991 the number reached almost 70,000. That’s 6000 more state rentals than New Zealand has today, even though our population is 46 per cent larger.

David and Mary McGregor standing outside 12 Fife Lane in 1978. They bought the house in 1952, when the National government was encouraging the sale of state houses to tenants. In the early 1980s it was repurchased by the Housing Corporation. Photo: Archives New Zealand/Te Whare Tohu Tuhituhinga O Aotearoa.

The HCNZ was loathed by those on the right of the then-Labour government, which was deregulating and corporatising swathes of the economy and government operations. They were itching to expose housing to the forces of competition, as was Treasury, which wanted to replace the bricks and mortar of state houses with housing vouchers for poor people. This pressure was resisted by those who believed that housing was a fundamental human right and that the state had a critical role to play in its provision, including Helen Clark, the minister responsible in the late 1980s. “Vouchers don’t build houses,” she told the frustrated reformers on taking the role in 1987.

A change of government cleared the way. In 1991, the newly elected National government, led by Jim Bolger, announced the most radical housing reforms since Savage launched the state-house building programme in the shadow of the Great Depression. The state would retreat, and the private sector would fill the gap. The forces of supply and demand would work their magic, and everything would be fairer and more efficient.

Government mortgages that had financed low-income families into houses were sold off in a $2.4 billion programme of privatisation. The state house portfolio was turned into a profit-making operation called Housing New Zealand. Income-related rents for state houses were replaced with market rents.

A single form of assistance was introduced for those who couldn’t afford market rents, along the lines of the voucher system Treasury wanted. The new accommodation supplement would cover 65 per cent of the cost that struggling families couldn’t afford; it was up to them to come up with the rest. National’s minister of housing, John Luxton, said this would be an incentive for families to keep their costs down.

The supplement would also be tenure-neutral — meaning that tenants of private landlords and state houses could qualify for it, and even those struggling to meet their mortgage payments.

There had been plenty of advice that the accommodation supplement was a bad idea. In 1988, the National Housing Commission had warned that such a system would “add little to the total housing supply while allowing private landlords and property speculators to make even higher charges for a non-expanding supply of housing”, which would in turn “raise the purchase price of land and rented property”.

John and Winnie Nysse and their children, Theresa, Joana and Sophia, outside the same Fife Lane house, now their home, in the late 1990s. Photo: New Zealand Herald. standing outside 12 Fife Lane in 1978. Photo: Archives New Zealand/Te Whare Tohu Tuhituhinga O Aotearoa.

The Salvation Army’s Major Campbell Roberts served on a working group set up by the new government to analyse the accommodation supplement proposal. It, too, concluded that the cost would be enormous and the scheme would do nothing to add to housing supply. The group was disbanded, its report sank without trace, and the government pushed ahead.

Luxton reasoned that the new system would give low-income tenants the flexibility to choose the house that suited them, whether it was rented from the state or a private landlord. No demands were made on landlords, who received subsidised rent regardless of whether the property was mouldy or healthy, frigid or warm.

With the government fulfilling its duty to poor households via the accommodation supplement, it started to sell off state houses. By the end of the 1990s there were fewer than 59,000, 16 per cent less than a decade earlier. Maintenance on those that remained fell away, not least because Housing New Zealand now had to pay dividends to the government.

The housing changes went hand-in-hand with the Bolger government’s headline reforms: deep cuts to welfare benefits and radical labour-market deregulation that forced down wages for many.

Roberts says the changes triggered “overwhelming need” in South Auckland, where he lived and worked as the Salvation Army’s director of community services. There was serious deprivation even before the reforms, and the army and other agencies provided emergency housing in state houses that they rented for $10 a year. Now they had to pay market rents. The Army had enough resources to continue providing shelter, but most community housing groups couldn’t.

Some people were quick to exploit families thrown into difficulty. Roberts recalls finding one family living in a six-by-four shed in a landlord’s backyard, paying rent yet barred from using the toilet and bathroom in the house.

Ioane Vaelei, Shelley Asesela and their six daughters. The family was living in a one-room motel. Photo: Dean Purcell, New Zealand Herald.

Prior to the reforms the Salvation Army had resisted the idea of food banks, instead giving needy families vouchers to local supermarkets. Afterwards, the level of hardship was such that food banks sprang up as essential social infrastructure.

Researchers at Lower Hutt’s Family Centre found some people were paying up to $2000 a year more in rent at the same time as their benefits had been slashed. Some state house tenants quit because they couldn’t afford the rent — in Cannon’s Creek, Porirua, the local school roll plummetted as a result. By 1997 the Catholic Office for Social Justice was reporting families living in tents, caravans, garages and emergency shelters while state houses sat empty. Schools in parts of Auckland saw a massive churn of pupils as families who couldn’t afford rent shifted continuously. Some went into debt to pay the rent.

Single mothers, Māori and Pasifika families suffered disproportionately. By 1998, the National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability was linking increased incidence of tuberculosis and meningitis with overcrowding caused by market rents. The minister of housing at the time, National’s Murray McCully, responded to reports of severe distress from social service agencies by accusing them of headline-hunting and scaremongering.

Through the 1990s, the government also largely stopped providing discounted home mortgages. Commercial banks piled into the market. By then inflation had been tamed and mortgage rates were mostly down to single figures. Despite that, home ownership rates began a long decline: by 2001, just over two-thirds of New Zealanders owned their home, compared with three-quarters a decade earlier. The rate of decline was steepest for Māori and Pasifika households.

The reforms had collapsed a once multi-pronged housing system into a single blunt tool — the accommodation supplement. As predicted, not only did it fail to stimulate new housing supply, the cost blew out, doubling to almost $800 million between 1994 and 1998. By 2020 that cost was budgeted at $2.4 billion.

The accommodation supplement remains a central plank of our housing policy, despite failing for 30 years to live up to Luxton’s promise of fairness and efficiency. Recent research by Saville-Smith and Ian Mitchell shows 350,000 households who receive it still pay more than 30 per cent of their income on rent — the benchmark for housing stress — and 130,000 pay more than half.

As for the question of efficiency, the accommodation supplement is best thought of as a high-pressure pipeline of government cash that ends up mostly in the pockets of private landlords. It is New Zealand’s second biggest item of welfare spending after National Superannuation. And each year the pipeline must pump harder and faster to match what has become a self-reinforcing cycle of falling home ownership, rising rents and increasing housing stress.

The story of Mark Gosche’s family is the story of a system that once shared housing wealth relatively equitably. His father came from Samoa in the early 1950s; his mother was brought up by her mother in Otahuhu, and left school before she was 15. They lived with his grandmother, saved a deposit, and got a 3 per cent loan from the State Advances Corporation, a precursor to the HCNZ. The house cost $5000, in a Papatoetoe street full of houses mortgaged to the State Advances. Gosche’s father worked variously as a baker, steel worker and meat worker, and often had a second job as a pub bouncer. His mother cared for the children at home. As the family expanded they capitalised the family benefit to add another room to the house.

“That was the way many families got into home ownership. There were seven of us [children], and six of us are homeowners now,” says Gosche, who is the chairman of Kāinga Ora, the modern iteration of Housing New Zealand. “That is really the thing that’s missing now.”

Saville-Smith’s latest research goes some way to explaining why that is. Back in 1986, 14 per cent of our houses were rentals. By 2018, 27 per cent were. Of the almost 576,000 occupied dwellings added to New Zealand’s housing stock over those years, around half are in the hands of investors. In recent years, this trend has intensified. Between 2013 and 2018, the housing stock increased by over 100,000 occupied dwellings, of which 81 per cent were owned by private landlords.

Furthermore, investors have not increased their portfolios by building new homes. Instead, they have done so by buying up existing houses, says Saville- Smith. “This is a profound transformation by which the housing market has, in reality, become a property market.”

She identifes three key causes. First, after the 1991 reforms, landlords quickly realised that the accommodation supplement was a massive new subsidy that would benefit them, and that the move to market rents in state houses would push more tenants into private rentals. Second, investors had fled the sharemarket after the 1987 crash, and residential property looked like a safe bet by comparison. Third, commercial banks that had been liberated from stifling regulation by Roger Douglas were eager to pour credit into the market.

Mark Gosche (back left) in front of the home his parents purchased on a modest income with the help of a state-backed loan. Photo: Supplied.

Using the word “investor” to describe people who have bought all these houses is something of a misnomer, however. In all likelihood the great majority are more accurately called speculators. The evidence for this lies in recent research by Michael Rehm, a University of Auckland property lecturer, and PhD student Yang Yang. They looked at 117,000 rental property purchases in Auckland between 2002 and 2016 to see if these deals stacked up in any conventional investment sense — that is, whether after paying interest and other costs and receiving the rent, there was a fair rate of return. They found that more than 99 per cent of purchases would not have met that threshold, and that therefore the buyers were speculating in the expectation of tax-free capital gains. Auckland’s market, they concluded, “is a politically condoned, finance-fuelled casino.”

Consider now what kind of houses have been built over these last 30 years. Before the 1990s, governments of both parties had financed the construction of modest houses for ordinary people — building state homes, funding granny flats, writing concessionary first-home mortgages. After the 1991 reforms this source of capital almost vanished.

A research team including Saville-Smith and Charles Waldegrave of the Family Centre research agency has revealed the consequences. Before the early 1990s, around third of all new house construction was low-cost homes, in the bottom quartile of value. A very small proportion were high-end luxury houses. After the reforms, the proportion of low-cost construction collapsed. By 1996 it was down to about 15 per cent, and by 2014 it was barely 5 per cent.

The state had been shunted out of the way and the private sector unleashed, but it turned out that the market wasn’t interested in building houses for poor people and those on moderate wages. Instead, the building industry followed the money up-market — by 2014, around 60 per cent of new houses were in the most expensive quartile.

Covid contact tracers doorknock at houses in Auckland to find as many as 27 people living under one roof.

Although the Labour-led government of Helen Clark elected in 1999 rolled back major parts of the 1991 reforms, it wasn’t enough to repair what had become an impoverished housing system. Income-related rents for state house tenants were restored, and state house sales were stopped and new ones built. By the time Clark’s government lost the 2008 election there were 67,600 state houses — fewer than in 1991, and in the meantime the population had grown by nearly 800,000. In the early 2000s, mortgage wars broke out between the banks, pumping more and more credit into housing. There was a vibrant industry in property seminars, teaching aspiring landlords how to leverage against the family home to buy rentals, maximise the tax write-offs, and enjoy watching their capital gains accumulate (tax free) as house prices doubled in seven years.

After the Global Financial Crisis, central banks everywhere made it exceptionally cheap to borrow money. House prices went nuts, especially in Auckland, and loan-to-value ratios were brought in to protect the banks and a bright-line test to crimp the most brazen speculators.

The National-led government of John Key sold thousands of state houses, including to community housing providers. According to economist Shamubeel Eaqub, by 2017 the ratio of state houses per 1000 people was lower than at any time since the 1940s.

During this period, New Zealand started importing huge numbers of people. We went from losing more than we gained through migration in the summer of 2013, to a net increase of nearly 65,000 in the winter of 2016. All of these people needed somewhere to live.

In 2018, April Cohen and her children were sleeping in the lounge due to the damp conditions of their Housing New Zealand flat. This caused Riley, aged 8, to have repeated asthma attacks. Photo: Ross Giblin/Stuff.

It was about this time that the tsunami of housing poverty hit with force. Social agencies reckoned over 40,000 people were homeless. Reporters and activists recorded the stories of children who were going to school and adults to work from dacron sleeping bags in the back seats of parked-up vehicles. Key insisted there was no crisis, that there had always been homeless people. But the pressure built to the point that his government started shifting people from cars to motels.

And now here we are in the winter of 2021. New Zealand is awash with cheap credit printed to stave off the economic impact of the pandemic, and house buyers are borrowing record volumes of it. Prices soared by a third in 12 months, on top of the 234 per cent increase in the two decades before Covid. Analysis by Stuff journalist Charlie Mitchell shows that on any number of measures our housing is the most overpriced in the OECD. Across the whole country the average house costs $890,000. Those able to buy their first home are taking on a debt millstone of more than half a million dollars on average. Those who can’t must pay rents that have ramped up at twice the rate of wages over the last decade. Having poured petrol onto the housing conflagration, the Reserve Bank is now looking to stem the flow of credit through tighter loan-to-value ratios and the threat of debt-to-income ratios. A large programme of state house building is underway, yet we still have 6000 fewer than we did in 1991. More than 24,000 households are in a social housing queue that is finely graded according to need; only the most utterly desperate get a house. In the first three months of the year more than 8000 households (4000 of them families with children) were warehoused in motels, camping grounds, hostels and other emergency housing.

Anecdotally, Covid contact tracers doorknock at houses in Auckland to find as many as 27 people living under one roof. About 38,000 children a year end up in hospital with diseases like rheumatic fever, cellulitis and pneumonia, caused or inflamed by cold, mouldy, crowded homes, according to an upcoming report by the Royal Society Te Apārangi. These kids are 3.6 times more likely than others to be re-hospitalised, and 10 times more likely to die in the next 10 years.

Leilani Farha, the United Nations’ special rapporteur on housing, has declared New Zealand’s situation a human rights crisis — one that would have been avoided if housing had been treated as a “human right and a social good, rather than as an asset for wealth accumulation”. New Zealand’s chief human right’s commissioner, Paul Hunt, accuses successive governments of failing on a “massive scale to deliver on the right to decent housing”, and is planning an inquiry.

Those of us who own houses are richer by the day. Homeowners and property investors had a windfall $217 billion boost to their housing wealth in a year dominated by the pandemic. And banks, for whom mortgages now make up over 60 per cent of all loans issued, are profiting more than ever.

We know New Zealand ceased being an egalitarian society some time ago, yet the figures are no less striking. The richest 1 per cent own 20 per cent of household wealth (including houses, trusts, shares and business assets); the top 10 per cent own 59 per cent; and the poorest 50 per cent — 1.4 million adults — just 1.7 per cent, according to recent analysis by Max and Geoff Rashbrooke and Albert Chin.

With wealth comes opportunity — to take a holiday, go to the dentist, eat well, pay for the kids’ extra maths tuition, take out private health insurance. Wealth brings the ability to plan for the future, knowing you have the resources to ride out the rough times. The ownership of houses sits at the core of New Zealanders’ wealth.

But even those lucky enough to land on the winning side of our fractured society are not immune to anxiety about where all this is heading. National’s housing spokeswoman Nicola Willis rejects the proposition that those of us who have houses don’t care about the plight of those who have not. When she talks to core National supporters she hears “huge” concern from current homeowners, who say “‘I’m really worried for my kids because they’ve given up on the idea of home ownership’, or ‘My kids might be able to buy, but what about the teachers, the nurses, the police who have given up on that aspiration.’”

And many homeowning parents struggle with the need to help their children buy houses while also protecting the family’s wealth. According to one estimate, 70 per cent of first-home buyers need the Bank of Mum and Dad to help with a deposit — which can be well over $200,000 on an average house in Auckland. Banks often refuse to allow that debt to be secured as a mortgage, and so parents end up gifting the money. But what if the son or daughter is in a relationship that fails and half of that money leaves with the estranged partner? Lawyers recommend pre-nuptials to deal with this risk — resulting in the awkwardness of planning for the possibility of separation when a young couple is just starting out.

And what if there are younger children? By the time they go to the Bank of Mum and Dad, the required deposit will — assuming ongoing house price inflation — be much greater. How to treat all siblings fairly? What if the money given to the first child has to be recalled in order to give equivalent help to the second? Lawyers say even in the most loving families, these situations are causing huge strains. Yet if the parents are not able to help, they’re likely to see their children destined to a life of renting.

As Mark Gosche notes, there has always been housing stress, “but the cancer has grown from the people at the bottom of the heap, the working classes, and it’s moved into middle class New Zealand, which is why everyone is so upset about it”.

Pretty Blenheim comfortable town with easy access to mountains and the magnificent Marlborough Sounds. The median house in the region costs $705,000, up 56 per cent on a year ago. A relatively healthy 72.5 per cent of households own their homes.

What is less visible is that the region also has the seventh highest rate of severe housing deprivation in the country. At last count, 421 people were either lacking any shelter at all, or in temporary accommodation, or living in dilapidated or overcrowded buildings.

In that winter of 2016, when families and workers were living in cars in Auckland, things got much worse in Blenhiem too. More people started turning up at John’s Kitchen, a service of the Crossroads Marlborough Charitable Trust which provides meals and support services. At that stage there were 38 households in the queue for social housing in the area; by the winter of 2017 that had doubled. Rents were going up like crazy, and migrant workers brought in to labour on the vineyards added to the competition for low-cost accommodation.

The government — then led by Bill English — pressed a motel complex, the Brydan, into service as short-term transitional housing (although not before a legal battle with neighbours, who said it would damage their house values). The Christchurch Methodist Mission was commissioned to run it, along with nine units in another motel complex and 19 houses.

Jill Hawkey, executive director of the mission, says that 800 people have been through the service since it started, mostly families. “That’s 3 per cent of the population in a rich little town.”

Just over 70 per cent of Blenheim’s residents own their homes. Photo: Andrew Macdonald.

She reaches for a thick, narrow scroll of white paper, tied with a ribbon. On it is printed the first names of those 800 girls and boys, women and men. She unfurls it across the floor of her Christchurch office, and it runs off in a tangle; it seems an apt metaphor for a system that can leave people stranded in motels for years at a time.

“It’s just appalling, isn’t it?” says Hawkey. “Think about it in terms of people’s lives, and the impact on each one of those kids who hasn’t had a home.”

Another version of this problem is playing out in Wairoa, a town that sits in a bend in its namesake river in northern Hawke’s Bay. It’s never been a prosperous town, more likely in recent years to make the headlines for industrial strife at the Affco meat plant, its major employer, than for real-estate news. Yet last year, house prices grew faster than anywhere else in the country — the median was up by more than $100,000, a rise of 63 per cent.

The increase is not because the meatworkers suddenly negotiated a fabulous wage increase. According to Shamubeel Eaqub, it’s because houses there are cheaper than regional centres like Gisborne, Napier and Hastings — not to mention Auckland. The rush of interest in Wairoa’s housing market has come from investors, who find they can earn a good yield here, homeowners freeing up equity in more expensive centres and moving to the area, and a few locals buying their first home.

In the winter of 2016, there were six households in the district waiting for social housing; now there are 84. Ten percent of the population lives in crowded homes.

It’s not just Blenheim and Wairoa, of course. Eaqub has constructed maps and graphs that convey the spread of what he calls the “infection” from the metropolitan centres to the towns. In the Far North, for instance, the median house price ramped up 38 per cent in the last year to $730,000, and 348 households are waiting for social housing; in Taupo, prices are up 32 per cent to $730,000, while 129 wait desperately; and Masterton, up 35 per cent to $602,000 with 132 household waiting for social housing.

“Our cities have become so hostile to their citizens we are exporting our people to places that have few job opportunities,” says Eaqub.

Jordan King is a 33-year-old sociologist whose area of study is ideas, and who controls them. The idea that the state ought to play a central role in building a society based on home ownership prevailed for decades, until in 1991 it was deemed heretical.

The idea that private capital should look after the provision of housing has been given a good run, and after 30 years the outcome is a humanitarian disaster. It has created what King calls a “two-track society” of owners and non-owners.

“Increasingly, your security and access to opportunity and your ability to put down roots and flourish as a member of our society will be determined by access to housing wealth,” says King. On the owners’ track there will be stability, children who can stay at the same school and therefore do well, better health (because home-owners’ houses are in better repair than rentals), and the wealth stored in owners’ properties will compound. On the non-owners’ track, there will be no accumulating housing wealth and the disadvantages of housing poverty — in terms of education, health, community ties — will compound.

The vast majority of Māori and Pasifika people are already well down the non-owners track, their rate of home ownership having fallen to 31 per cent and 21 percent respectively, leaving them highly dependent on the private rental market and massively overrepresented in the homelessness data.

“Then there are the political impacts,” continues King. “Those who can afford to participate in politics have always had a greater advantage, because it’s a question of time and resources. Politics revolves around the median voter . . . and on their side will be the interests of those who do really well out of the system — banks, the real-estate industry, landlords, property managers.”

A few years ago, King and others got together in one of their flats and formed Renters United to lean against these forces. They helped build the case for the recent tightening of tenancy laws, which mean that landlords can no longer evict without cause, are barred from raising the rent more than once a year (albeit without any effective limit on how much it can be jacked up), and must permit tenants to make small alterations, like hanging pictures on the wall, to make their rental a home.

A time bomb of poverty among the elderly is coming, as increasing numbers reach retirement without their own home.

Landlords are now also obliged to insulate their rentals, install heating and bog up the gaps around the doors and windows (requirements that have so far met with widespread non-compliance, according to the New Zealand Herald). But even allowing for these changes, New Zealand tenancy laws remain weaker than in many other countries. A tenant can still be booted out because someone in the landlord’s family wants the house or if the landlord decides to sell. There is no law preventing a family being evicted into homelessness. Compare this with Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Japan, which have high security of tenure — for example, having restricted “just cause” grounds for terminating a lease, or requiring a court to ensure eviction is reasonable given the competing interests of the tenant and landlord, says Mark Bennett, of Victoria University of Wellington’s Law Faculty.

Renters United is pushing for rent controls, a proposition dismissed by the likes of the pro-market New Zealand Initiative, which says this would drive landlords out, making the crisis worse. But 13 of the 26 OECD countries have some form of rent control. In the Netherlands, rents are subject to maximum increases; in Sweden, they are collectively bargained with the Swedish Tenants’ Union; in stressed rental markets in France, city governments can impose controls.

And the precarity of renting is no longer the preserve of young adults or even young families. The coming years will see more and more old people renting from private landlords. National superannuation was designed on the assumption of mortgage-free home ownership, with retirees therefore able to live modestly on their pension. In the early 90s this assumption seemed sound, with close to 90 per cent of people reaching retirement as homeowners.

But by 2013 almost a fifth of those over 65 were renters, an increase of 44 per cent since 1986. In 20 years we can expect fewer than 50 per cent of people turning 65 to be homeowners. Think about what this means in terms of current superannuation rates and average rents: a single retiree renting a modest one-bedroom flat in, for example, Wellington’s Miramar or Auckland’s Avondale would be forking out around $350 a week from their $437 pension. The accommodation supplement would help, assuming they qualified for that modest assistance, but even so it points to a difficult life.

“It’s somewhat hidden now but it’s only going to get worse,” says Bev James, a housing researcher in the Building Better Homes Towns and Cities national science challenge and previously with the Ageing Well science challenge. Older people forced to pay a large chunk of their income on rent will cut back on food, clothing, heating and visits to the doctor, she says. If their landlord terminates their lease, they’re forced out into the market with everyone else — traipsing around viewings, finding thousands of dollars to cover bonds and advance rent and to move their belongings. They may even have to shift to a cheaper area. “Bang, there go your social connections,” says James.

Invercargill City Council housing unit tenants’ association members (from left) Nehua Henare, Norman Agnew, Ken McNaught and Leisha Kennedy want to have a collective voice when discussing issues with the council. Photo: Luisa Girao.

Seniors rarely get on the Ministry of Social Development’s priority waiting list for social housing, she says. “And who is building affordable rentals for older people?” Councils once did, but now most are not.

In Auckland, the New Zealand Housing Foundation sees the looming crisis of housing poverty among older people and is considering a scheme that could help. The foundation was set up in 2001, with backing from The Warehouse founder Sir Stephen Tindall, to assist low-income working families move into home ownership, via shared equity and rent-to-own schemes. It has lifted 400 households out of the rental market over the years. In a typical situation, a family will have enough money in KiwiSaver for a deposit on, say, a 60 per cent share of a modest new house and enough income to sustain a mortgage for that share. The foundation holds the remaining 40 per cent, funded through a combination of reinvestment and new funds, including from the government’s Progressive Home Ownership fund.

The foundation’s chief executive, Dominic Foote, thinks this concept could also work for people who reach retirement with some equity in their home, but with outstanding mortgage debt. While the concept is still to be tested, the thinking is that the equity could be invested as a share in a modestly priced apartment, with the balance owned by the foundation which may need to charge some rent to cover costs. The benefits for the retiree would be secure tenure, a share of capital gain on the property, and freedom from the vagaries of the private rental market.

Researchers, activists, community housing organisations — there is so much intelligence, dedication and drive being applied to this crisis. But it can seem like a drop in the ocean of misery. Their resources are a pittance compared with the monumental scale of the 30-year housing deficit, and their energy is up against the dedicated inertia of those who benefit from the status quo.

Some think New Zealand is on a cusp and things could go either way: an accelerating concentration of power and wealth in the hands of property owners and rentiers; or a reassertion of the notion of housing as a human right rather than a tool of speculation, and the development of deep partnerships between government, community housing groups, iwi, civil society, and ethical investors to turn things around.

At central government level there is more action on housing than there has been since the 1980s. Kāinga Ora has a huge building programme and is aiming to bring the number of state houses up to 81,000 by 2024; $3.8 billion in government money is tagged for housing infrastructure (water pipes, sewers, roads) and Māori housing projects, and there’s the $400 million progressive home ownership fund. The RMA is to be replaced, and there’s a new national policy statement on urban development that directs councils to plan for high-density housing.

But there is also great frustration, particularly among community-housing providers (of which there are around 80, including the Salvation Army and the Christchurch Methodist Mission). They already provide social housing for around 25,000 people who qualify for the government’s income-related rent subsidy. Housing minister Megan Woods says she is building a “partnership” with the community sector, and that they’ve been able to build more houses in the last year than ever. But they point out that even if Kāinga Ora manages to deliver on its building targets, the number of houses will still fall thousands short of the current social-housing waiting list. They argue they could do far more to add to the supply of affordable housing if they were able to draw on the government’s balance sheet through a guarantee or underwrite.

In the absence of that, an innovative financing organisation has emerged to tap into private investment capital for the construction of social housing. Community Finance was set up two years ago by James Palmer, a lawyer and formerly chief executive of Christian Savings, and Paul Gilberd, who was previously head of strategy and development at the Housing Foundation.

Gilberd thinks Covid has brought a new understanding of the housing emergency, which has been borne out in the early success of Community Finance. Its first venture was a $40 million Salvation Army community bond to finance the construction of 118 well-designed energy-efficient homes for people on the social-housing waiting list. Philanthropic foundations were among the early investors, but Gilberd says the breakthrough was getting the first KiwiSaver fund — Generate KiwiSaver — on board. As well as getting a competitive rate of return on their money, the investors had the comfort of knowing that, because of the income-related rent subsidy, the tenants’ rents would be paid.

Since then Community Finance has raised a $10 million bond for CORT Community Housing, and recently launched a bid to raise $100 million for social housing. Over $70 million has already been pledged from investors including the ANZ, three KiwiSaver providers and philanthropists. They have also set up Positive Property, which will enable churches to invest blocks of land suitable for affordable housing developments in exchange for shares, with private investors then tapped for the finance required to build houses on that land.

It pales in comparison to the wealth that’s being accumulated by private landlords, who as Gilberd puts it, are “asset-stripping poor people who could be paying a mortgage and thereby, by definition, digging themselves out of poverty”.

But he speaks with the energy of a man who’s just getting going. Community Finance falls under the “impact investment” heading — investing for social and environmental good, while making a decent return for shareholders. He thinks there’s a powerful case for other KiwiSaver providers to follow early adopters like Generate and put a portion of their funds to work on helping to solve the housing catastrophe.

“There’s $82 billion in KiwiSaver funds, and even 10 per cent of that is enough to start seriously moving the dial on the housing crisis,” he says. “We’d be solving New Zealand problems with New Zealand solutions and New Zealand money.”

What $1.8 million will get you in Avondale, Auckland, in 2021. Photo: Supplied.

Indeed, there is plenty of money. In their research on the accommodation supplement, Kay Saville-Smith and Ian Mitchell calculated that if the $186 million a year going to tenants with household incomes of over $100,000 was channelled for those families into progressive home ownership, in three years it could stimulate the construction of $1.6 billion of low-cost housing, lift these households into independence and relieve stress on the rental market.

Perhaps it can be done; perhaps it is possible to rebuild the wrecked home-owning democracy, bridge the social and economic chasm between owners and non-owners, and reverse the enormous harm being inflicted on children through housing poverty. It all depends on what we choose to do, and how urgently. In 1991 a catastrophic path was chosen and we are still stuck on it, at vast humanitarian and fiscal cost.

It is hard to go past Major Campbell Roberts for a last uncertain word on this. He has been out there for decades, serving the poor with shelter and care, fighting complacency, and trying to reason with ideologues and fantasists. He’s 74 now and still serving, including on the board of Kāinga Ora.

Does he think our housing catastrophe can be fixed? “There are more hopeful things happening at the moment than I have seen in a long time. But the answer is I don’t know. I am hopeful in the sense that I am prepared to put all of my remaining energy into trying to bring about some change . . . But we are so deep into this, the results are going to be long term.”

Secure housing is at the centre of wealth accumulation and wellbeing, and the lack of it is at the heart of our chronic poverty. There is no fixing the scourge of third-world diseases, childhood deprivation and educational under-achievement without fixing housing.

Thirty-three years ago the National Housing Commission noted that our collective abhorrence of poverty was a key defence against housing failure. As we stand now at the cusp, the question for those of us on the winning side of the class divide is whether we can rediscover that abhorrence of poverty, or if we are content to watch our wealth accumulate while the emergency compounds into a calamitous future of exclusion, desperation and discontent.

Disclosure: Rebecca Macfie and her husband own a mortgage-free family home in Christchurch and a small bach in Arthur’s Pass.

This story appeared in the September 2021 issue of North & South.