You’ve Seen Kris Sowersby’s Work Everywhere. You Just Don’t Know it.

The stunning global success of typeface designer Kris Sowersby of Klim Foundry.

By Ashleigh Young

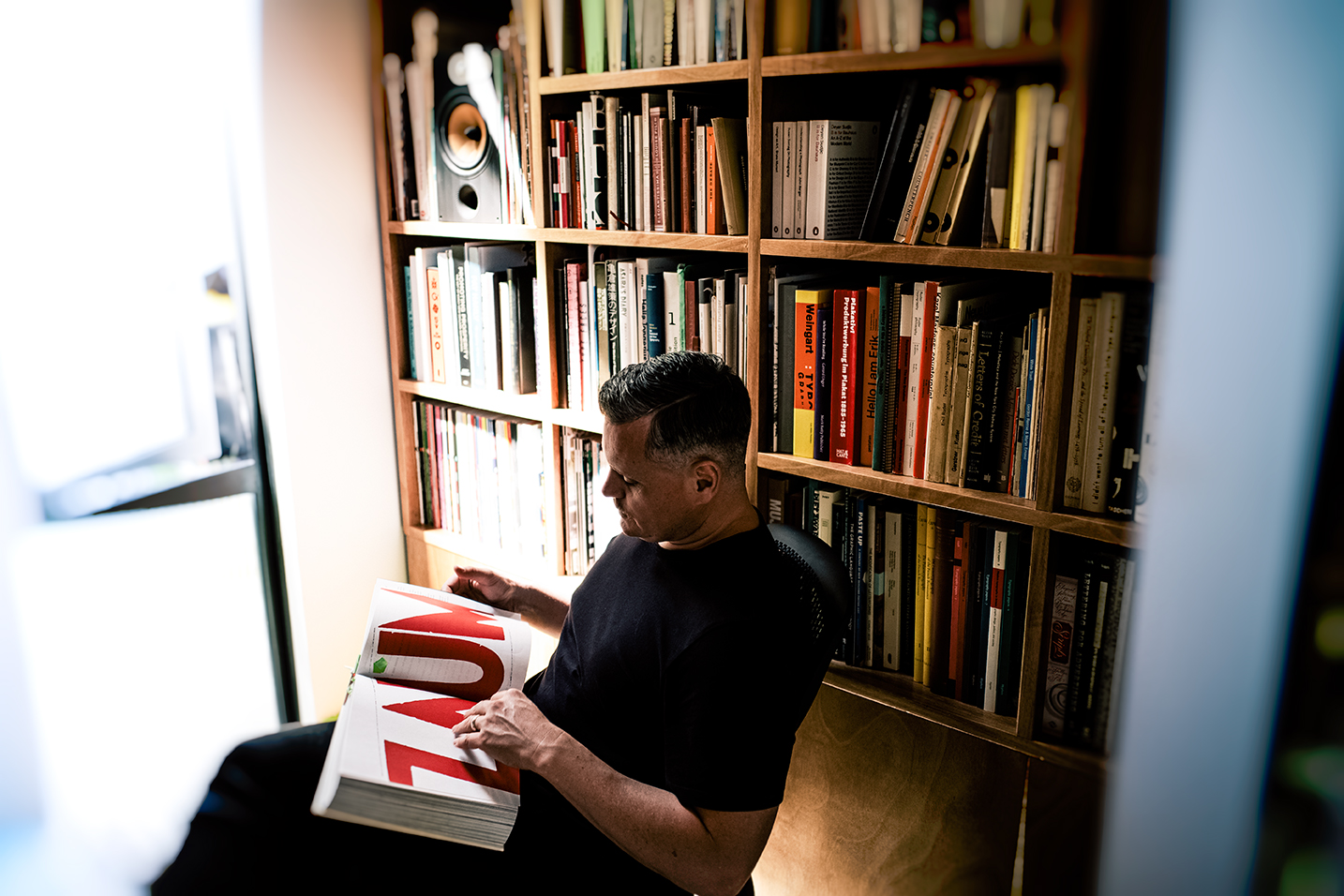

Photography by Cameron McLaren

It’s embarrassing to call anyone who isn’t a literal rock star the rock star of anything else. Unfortunately Kris Sowersby of Klim Type Foundry has been called the rock star of type design many times. It’s not his fault; it’s just that he’s formidably good at drawing letterforms, and when we think of virtuosity we always turn, lazily, to rock stars. A better analogy might be that he is the taxi driver of type design. He’s one of the drivers with an enlarged hippocampus from memorising the city, so he has ingenious ways of getting anywhere. Or maybe he’s the ecologist of type design, and he’s on a rewilding mission, out there with a spade, recreating habitats for native flora and fauna. “I don’t know,” he says. “Maybe it’s like being a farmer and supplying all the restaurants with your carrots.”

He’s right, but in terms of versatility and earthy beauty his typefaces are probably more like potatoes. (I should mention that the words typeface and font are often used interchangeably, especially by non-designers like me, but that technically a typeface is a collection of fonts with a common design ethos — or “atmosphere”, as Sowersby says — each in specific weights, styles and sizes.) Sowersby’s influence is everywhere, though in many ways it is magnificently invisible. He’s created Geograph for National Geographic, Financier for the Financial Times, Pure Pākati for Tourism New Zealand. Other clients include PayPal, Apple, BNZ and Trade Me. His fonts are in ads and logos and political campaigns and all our bank notes. And books: I use them in my work at Victoria University Press. “Some people spend way longer with my fonts than I ever have, which is terrifying,” he says. “I feel a bit sorry for them. Well — no, not really.” He even typeset my brother’s CV when they were both living in Whanganui in the early 2000s, and my brother used it to get a job in London and then just never came back. He also has an idea for the cover of this magazine: him in roman (“me standing up all straight and proper”), italic (“me falling sideways”), and bold (“really fat”). “I’m not sure if they’d go for it.”

Sowersby is full of shouty laughs, swear words and strong opinions. In a recent Idealog interview his voice is described as a fusion of Jermaine Clement and Shayne Carter, which is right. It’s the slight raised eyebrow in the voice, the deadpan intellect. But he’s a bit more softly spoken, and also kneads his face a lot as he talks, as if trying to squash it into another shape.

Outside his home in Miramar, construction of the Font Bunker is underway, a small studio that will at last provide some kind of division between work and home. For three years he and his wife, Jess, have been working at home with their young daughter, Indy, and their needy griffon, Pickle. In that time, with Jess as studio manager, they’ve released a flurry of fonts, including Söhne, Heldane, the bonkers Maelstrom — a reversed-stress typeface that looks both forceful and fragile, like a robot writing a love letter, but which Sowersby describes hilariously as “kind of ugly and useless” — and the twin workhorses Untitled Sans and Serif, which came out of the question, “What if you just need to set text with something . . . utterly normal?”

“We crave new letterforms,” Sowersby has written, “finding them at once fascinating, repulsive and intoxicating.” I like how he describes typefaces as if they’re people in a Scorcese film.

Born in 1981 in Hastings, Sowersby remembers wanting to be a truck driver and arm wrestler, like Sylvester Stallone in Over the Top. Other career thoughts were orthopaedic surgeon (“I just really liked drawing skeletons”), sculptor (“I wanted to gross out my teacher by making really gory sculptures of people with their guts falling out, things like that”) and special-effects designer, though he consciously killed that dream, deciding he’d never be good enough. He remembers being impressed by The Lettering Book — the groundbreaking book full of letters and numbers that you could trace, elevating your social studies project from ham-fisted to masterful — but it wasn’t until studying at Whanganui School of Design that he became properly enamoured with letters.

He has now reached the level of fame within his field where anecdotes about his early days are repeatedly told; one of them is about a moment when he decided to try copying in pencil the inescapable old-style typeface Bembo, a bit like young poets emulating Frank O’Hara (we’ve all done it). Bembo has its origins in the Roma letters that were cut — their shapes laboriously carved from steel blocks — around 1495 by Francesco Griffo, a Venetian punchcutter, who’d made the letters for a book the scholar Pietro Bembo had written about visiting Mount Etna in Sicily. In 1928, Griffo’s letters were revived as Bembo by the British type designer Stanley Morison. Sowersby says, “I remember drawing the lowercase ‘n’ and realising that the right-hand leg was slightly curved.” He wrote “Cheeky Bembo!” next to his sketch. The exercise revealed to him how subtle details could create an impression of warmth in the letters. (A few years later he wrote a terrific polemic titled “Why Bembo Sucks” lamenting its careless overuse and its evolution from lovely metal typeface into an “insipid digital ghost”.)

There is no defined path to becoming a typeface designer in New Zealand — or, not yet — and Sowersby is largely self-taught. He took the one module on typeface design at Whanganui, and after graduating spent three years teaching himself how to make typefaces. He tried to get a job in design but couldn’t, so ended up working at a signwriter’s in Nelson, where he had the deflating thought that “nobody gave a shit about design, they just wanted a sign”.

In 2005, he went out on a limb and founded Klim. It began its life as just him solitarily making typefaces, and although that is still the core of the business, Klim now encompasses a range of designers, developers and contractors and, crucially, his wife Jess, who early on saw the need for a business plan that would get the company properly off the ground. The name was partly inspired by seeing the word ‘ZAUM’ in the book The Art of Looking Sideways, which everyone had a copy of back then, and the futurist notion it represented of inventing words where the sound conveys meaning. “I started reversing words in my sketchbook, and ‘milk’ became ‘Klim’. It sounded vaguely European, and in the early 2000s we were cringey about New Zealand, in the design world particularly, so I thought, well that sounds good.” His work began to populate the landscape of text here and overseas, cutting vivid channels through the sea of American and European typefaces: Helvetica, Garamond, Times, Futura. It’s what he always set out to do — make typefaces here that are just as ubiquitous and useful as those from elsewhere. “We crave new letterforms,” he has written, “finding them at once fascinating, repulsive and intoxicating.” I like how Sowersby describes typefaces as if they’re people in a Scorcese film.

Fonts “have accents”, Sowersby says. “Bembo has this Italian-born but British-raised accent. Helvetica has a Swiss-German accent. I really wanted to make fonts with our accents, but it didn’t turn out like that.”

“They have accents,” he says now. “Like, Bembo has this Italian-born but British-raised accent. Times New Roman is very upright. Helvetica has a Swiss-German accent. And I really wanted to make fonts with our accents, but it didn’t really turn out like that. I wouldn’t say any of my typefaces look like New Zealanders. We don’t really have a culture of it here, where we can say — oh, yep, that’s a Kiwi letterform.” I say that I’ve often thought of his Untitled Serif and Sans as quite New Zealandy, in that they don’t look self-consciously designed: their ordinariness is the point, but they also have an elegant heft, an almost racehorse-like musculature. “I like meat on my bones. And I definitely have a style. I have a fist, as they say.” What? “Morse code operators, during the war, when they were trying to figure out who was sending what, could tell by a person’s fist — their specific way of tapping. Which is insane, when you think about it.”

One of my favourite Klim fonts is Heldane, a 2018 release which I recently used for Elizabeth Knox’s novel The Absolute Book. (Sowersby has read the book, and liked it. Yes, yes, but what about the typesetting? “It was lovely. It was almost like me speaking back to myself. It was nice to see it put through its paces, because I don’t often get to see that.” Thank God.) Heldane is a sharp yet sturdy serif, and it felt right for Knox’s book, an epic that reaches across both fantastical and familiar worlds. When choosing a font for a book, there are basic requirements — must be readable, must have a macron and all other necessary diacritics — but ultimately it’s an emotive and visceral choice, sort of like choosing a therapist. As Sowersby has pointed out, most typefaces have environments in which they shine (Caslon makes poetry look great); others in which they will always fail (Helvetica is too tiring for a novel); and a few work beautifully in absurd situations (Futura is on a plaque on the moon).

Sowersby likens the process of designing Heldane to that of recreating a Neanderthal face, where artists and scientists have only the ancient, crumbling skull to go by. “It is a hybrid, a bastard, a fabrication, ” he wrote upon its release. “I vultured my way through history picking the bones from old fonts I like to make something new.” This reminds me of what poets do — we’re scavengers. It’s fitting that the foundry accompanied Heldane’s release with a poem-as-specimen-book, Sincerity/Irony, by Hera Lindsay Bird.

When choosing a font for a book, there are basic requirements, but ultimately it’s an emotive and visceral choice, sort of like choosing a therapist.

This brings me to my ulterior motive for interviewing Sowersby. I want to talk him into writing a book. On my bike ride out to Miramar I devised a whole plan. He will write the book, I will edit the book, the book will be published and be a bestseller, and he will be famous. I got so excited about this idea that I kept forgetting that he is already famous. I am excited because the writing on his blog is a joy and a revelation. He describes one 19th-century typeface as having “strips of light sparkling through the black mass”. Sketching out a reversed-stress character set is like “reading upside down or talking backwards”. Of Signifier, he writes of an infinite sharpness that “is almost imaginary at small sizes”. It’s like reading about an underworld that is recognisable but also deeply strange.

“I mean, I have talked to a few people about a book,” he says, “just floating the idea of it.” Oh no. I do not tell him about the plan. “I would be writing for me — for the me of 20 years ago, when I was just starting out. It would be all the things I wanted to know then, demystified and given context. And it would have to be well-designed, but cheap. And I’d have to justify its existence.” Amidst the endless churn of newness, of making and consuming, this approach is unusual and exactly right.

I realised this while Sowersby was talking about Signifier, his “deathbed font”, which came out last year. “Hopefully, when I’m lying there reviewing my life, I’ll be glad I did that one,” he says. “I feel a massive creative weight has been lifted off my shoulders. I feel much freer.” Signifier is the typeface that he fell into a “philosophical rabbit hole” over. Designing it took him around 15 years. He’d been trying to figure out how to emulate the analogue printed forms of the 17th century — when fonts were made with materials like lead, tin and antimony — for our digital present. He figured out that he needed to stop working against the digital world, and work with it: consciously making the letters consistent rather than irregular, a process he likens to turning soundwaves to data or images to pixels.

Signifier is the typeface that that Sowersby fell into a “philosophical rabbit hole” over. Designing it took him around 15 years.

Designing any typeface begins with a lot of tentative sketching, after which he lets it sit for a while. “When I say a while, I mean months or years. Because, you know what it’s like when you first do something. You think, ‘God! I’m a genius.’ Then you come back a while later, and it’s: ‘This is shit.’ So there’s a lot of that.” Eventually the concept settles, and the production begins, which is mechanical and involves refining the weights, styles, and kerning (nudging the spaces between letters so they don’t crash into each other or drift too far apart). He has no beef with any particular letter. “Some are hard, like ornate lowercase ‘g’. Plain geometric ‘o’. But — it’s the process that’s the struggle. The classic saying is: a typeface is a beautiful collection of letters, not a collection of beautiful letters. If you’ve got one letter you’re really into, sometimes it has to be sacrificed to fit in with the whole.” What’s the hardest part? “The hardest bit is always finishing. Then the hardest bit is liking it.”

The essay that he wrote for the release of Signifier is intricate and unexpectedly moving. When he began working on the typeface, his mother was diagnosed with cancer. Last year, after she died, to help him in his grief, he read books that dealt with Buddhist notions of impermanence and temporality. He came to the realisation that Signifier, the very thing he had worked on for such a long time and into which he had poured so much of himself, was itself impermanent and immaterial. “We shape letters from numbers and draw curves with equations,” he wrote. “Letters are no longer things, but pictures of things transmitted by light.”

This completely upended my way of thinking about letters, and was a little unsettling — the realisation that when you sit down in front of your screen to write, every word is a picture of a word, every story a picture of a story. “There’s a kind of absurdity to drawing new shapes of letters on a screen,” he observes to me. “If you turn the power off, they don’t exist anymore. And it’s a relatively new phenomenon. People of our generation — we grew up with shit that existed.” He’s at peace with the ultimate transience of his work and legacy, which is unusual for a youngish artist. Most of us, if we’re honest, hope our books will never go out of print and our art will never decompose in someone’s garage. “My fonts aren’t going to be used forever. It’s kind of nice to think that they’ll be used for a while, and then . . .” he shrugs. “There’ll be something else.”

Ashleigh Young is a poet, essayist and editor. She received the Windham-Campbell Literature Prize in 2017 for her second book, Can You Tolerate This?

This story appeared in the January 2021 issue of North & South.