Culture Etc.

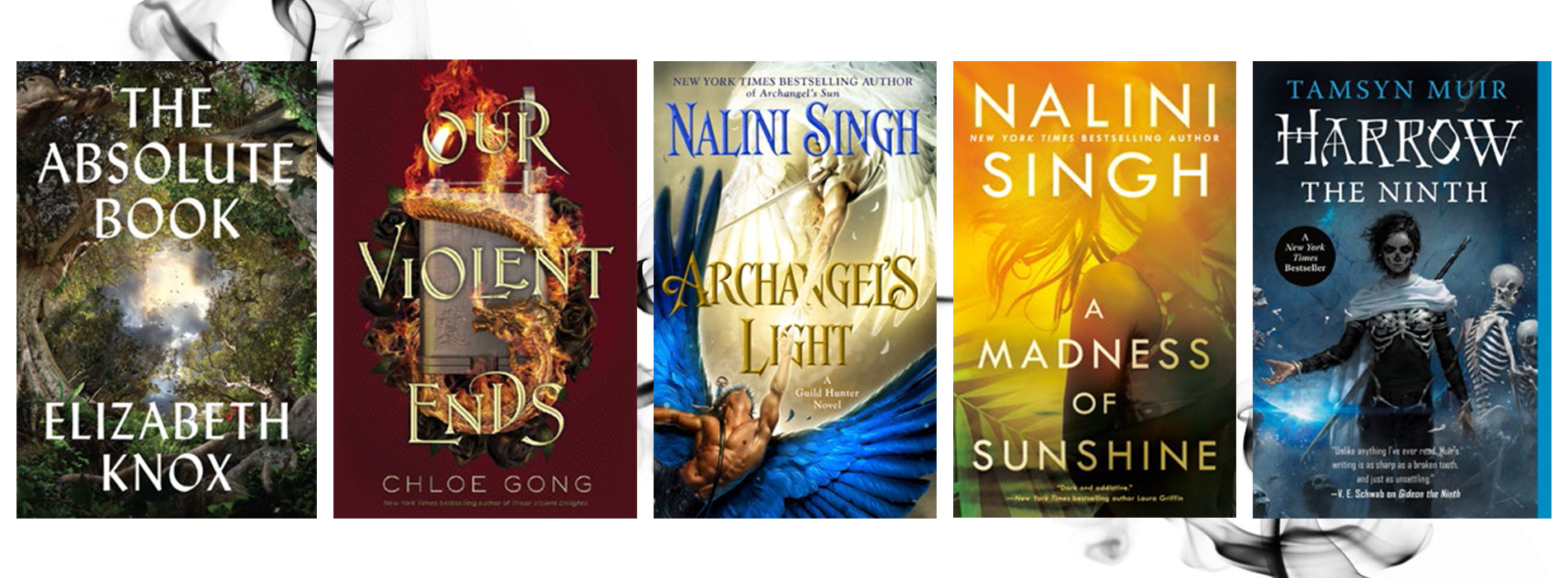

Above: Selected book covers.

Is This Just Fantasy?

Despite its immense popularity, genre writing like fantasy and romance struggles to be taken seriously by the literary establishment. Why?

By Tobias Buck

I once worked in a bookshop that flooded. Renovators upstairs had accidentally burst a pipe and water began pouring through the ceiling. Drips started to form in the crime section. As we rushed to protect tables of books a fire crew arrived — by chance they’d been walking by, seen us struggling and, convenient as a literary device, rushed in to help.

They had helmets. They had tarpaulins. It was all very surprising. Amid the watery chaos one asked, with some seriousness, “Should we move Fiction into Fantasy?” A tiny pause followed, a momentary hesitation among the assembled staff. Odd, under the circumstances. It felt like a philosophical query. Why not combine fiction and fantasy? Might this be the moment? As one well-known hobbit famously mused, rolling a golden ring between his fingers: “After all . . . why not?” Why shouldn’t I?

The separation between literary and genre fiction is paper thin yet persistent — from library shelves, award categories, writing workshops and prize money, to funding for writing and marketing. Fantasy is the undeniable mother of fiction, its ur-form, part of culture’s earliest storytelling. Every myth or creation story was a work of speculative fiction once. On ancient cave walls, in the ebook locations of the Epic of Gilgamesh or within the morality and fairy tales whose echoes appear in modern texts, fantasy precedes and informs literature, resonating through the ages.

As the concept of genre evolved and became formalised by the publishing world, its storytelling conventions were agreed upon by authors and readers alike. By and large, a genre writer today falls into a category by adhering to some pattern.

Modern fantasy authors, for instance, are advised to create the parameters of their fantasy world in advance, and stick to them. (One now-defunct publisher of time-travel romances even explicitly stated: “No time machines, please.” Those are strictly for science fiction). Romance novels usually end satisfyingly, with a happily-ever- after, and are often written from the heroine’s perspective. A mystery or crime novel focuses on plot after an early murder or misdeed creates a puzzle with Hansel-and-Gretel-type clues for the readers to follow. By contrast, while literary fiction tends to favour ambiguity and interiority, it’s a free-roam area.

Genre writing’s parameters are firm — one now-defunct publisher of time-travel romances even explicitly stated: “No time machines, please.” Those are strictly for science fiction.

Perhaps the defining difference between the two categories is that genre writing, which includes romance, mystery and sci fi, but also historical drama and others besides, generally gets less attention from those who decide what “serious” writing should consist of. The powers that be in the literary world don’t really count the categories shorthanded to “Swords and Sandals” or “Wizards and Dragons” (terms used to describe genre fiction as well as to deride it). The Booker Prize, the Western publishing world’s highest honour, is for books with a capital B. Here the literary equals the worthy. Each year the longlist is stacked with character-driven novels focused on some grand aspect of the human condition — the same type found on reading lists in high-school English classes. In New Zealand, the Ockham Book Awards are our highest literary honours. As with the Booker, the winning novels are usually grounded in the real world (bar a few highbrow experiments with form). They’ll be considered a runaway success if they sell more than a few thousand copies.

On the bookshop floor a single customer might slowly browse the large general fiction section while multiple crime or fantasy readers bee-line in and out of a smaller, and completely separate, part of the store. Though done for organisation’s sake, this siloing of writing styles reinforces a belittling attitude towards genre that ignores the quality and popularity of the work produced. Genre authors’ names are not unknown to their many thousands of readers and fans around the world, but they are curiously absent in discussions of our local literary scene.

Chloe Gong is 22 years old and one of the youngest authors on the New York Times’ bestseller lists. Nalini Singh has sold millions of books printed in more than 20 languages. Tamsyn Muir published her debut science fantasy novel, Gideon the Ninth, in 2019 and it was named one of the best books of the year by NPR, the New York Public Library and Amazon. All three are highly accomplished New Zealand authors whose books’ many successes have not garnered even close to the amount of attention of their literary and nonfiction counterparts.

Gong’s first novel, These Violent Delights, spent 19 weeks on the New York Times’ “young adult hardcover” bestseller list after being published last year. While Gong believes it’s important to give young-adult literature its own category, in order to let the reader know what they will find inside, she believes condescending treatment of YA contributes to its reputation as a fundamentally unserious form. The fact that YA is largely written for teenage girls, and with “teenage girls getting the short end of the stick from society at large”, means there are plenty of people out there who think YA isn’t real writing, Gong says. “Adults love sneering down at what teens love. I love writing for the teen audience, and . . . writing the sort of books I would have wanted to see on the shelves when I was 16.”

Having said that, like a lot of recent YA novels (a genre that has provided many lucrative hits for the publishing industry in the past two decades), the audience for Gong’s work extends well beyond teenagers. These Violent Delights is a sprawling historical novel set in 1920s Shanghai, a reworking of Romeo and Juliet as vivid as any other piece of fiction you might pick up.

Born in Shanghai, raised in Auckland and now based in New York, Gong wrote this bestseller at age 19. If that isn’t enough to make you feel like you’re not eating enough Weet-Bix, Gong is releasing her follow up, Our Violent Ends, this November, and has just graduated university with an English and international relations double-major in the United States. “I’m quite disconnected with the New Zealand literary scene,” she says, in part because she deliberately chose to publish in the US market. A search for Gong’s name yields a smattering of New Zealand coverage, about four stories, versus pages of headlines from news websites all over the United States. She’s not too bothered by this disparity, but does say she’d like to feel more connected with New Zealand’s literary scene — though you get the sense that should be on Gong’s terms. “Once I wrote the manuscript that was going to be my debut novel, I’d spent long enough on my own process that it had become ingrained in me to write what I knew I wanted to see, and to care very little about the rules that professional gatekeepers might try to set,” she says.

To an extent, romance novelist Nalini Singh also rejects arbitrary literary rules. “We don’t all have to be part of one literary group,” she says. “Such a goal is an impossibility. But by that same token any pronouncements about ‘the state of New Zealand fiction’ have to be taken with a grain of salt. The people making such pronouncements never give much thought to genre fiction — including the work of many local writers who quietly and regularly sell thousands of copies, paying their mortgages while never engaging with the ‘serious’ literary scene.”

Singh’s first novel, Desert Warrior, was published in 2003. In the nearly 20 years since, Singh says she’s come to understand that her joy as an author comes from her work reaching its intended audience. “That realisation has given me a deep sense of peace,” she says. “As a result, I rarely get up in arms on such matters on my own behalf.”

Many local genre writers “quietly and regularly sell thousands of copies, paying their mortgages while never engaging with the ‘serious’ literary scene”.

Romance is still, around the world, the most popular and most profitable genre of fiction. Despite this, Singh asks, when was the last time you saw a major article on a debut romance novelist? And, on the slim chance you remember seeing one, “was the article fair and professional, or did it make snide asides about romance?” Romance has always been the target of professional disrespect, Singh says. “We explore the myriad journeys of the human heart, telling the stories of the countless different ways in which people find their way to one another.” Some are dark and intense, others funny, others gritty and real. “Yet someone somewhere in the ‘literary scene’ has decided that the work of these writers, work that reaches millions across the globe, has no value.”

Singh has received emails and letters from readers across the world thanking her for putting people who look like them on the page. “People from marginalised communities especially, shouldn’t be subtly told that, to be worth sharing, their stories must be biographical, showcase tales of struggle, or be heavily based in exploring their culture,” Singh says. “If a writer who, for example, came to New Zealand as a refugee decides they would rather write romances or mysteries, why not support them? Their voice in the genre space will have an incredible amount of power — it could even reach into corners literary fiction never will.”

Both she and Gong raise questions about the gendered way we assign value to form. Most romance novelists are women, and so are their audiences. It seems that wider society has a propensity to treat work created for women or girls as less worthy of merit, even with scorn.

Tamsyn Muir writes beautifully vivid stories that pull the reader in; it’s almost as if she knows what you want to read next. Her books are pure captivation. Now based in the United Kingdom, Muir comes out with lines that pack more punch than most of what’s on Netflix, even in casual emails to journalists. “When you cut me I bleed L&P,” she writes to me, describing her New Zealand identity. “At night I dream of Cockle Bay Beach.” Muir is the author of the incredibly popular Locked Tomb series, the first instalment of which, Gideon the Ninth, spent weeks on US bestseller lists in 2019.

Like Gong, Muir feels a sense of disconnect to her home country’s literary scene, which she says is “pretty devastating”. “As a teenager I always loved the sense that Kiwis could wander far from home and they’d never be forgotten — Anna Paquin can live in LA and put on a Southern US accent for True Blood but we all know she’s still a Kiwi — and it’s been upsetting over the last couple of years to feel like that rule isn’t as reliable as I thought. I can’t even convince my old high school to put me on their ‘notable alumni’ page.”

Muir says that like most genre writers, she’s “nettled and defensive” at the idea that genre is somehow “lesser” than literary fiction — but is willing to admit that the latter can allow for more “gonzo” experimentalism. “There’s a point where a mystery novel simply isn’t a mystery novel any more, whereas you can’t have a literary novel that’s like, ‘This is so weird, it’s not literary.’” She thinks genre writers are more hesitant to risk playing with form because they have to “serve two masters that don’t get on very well” — art and comfort. More than literary fiction, genre is about escapism, ease of reading.

“Good books have life to them. Lots of it. Heyer, Chandler, Tolkien, Elmore Leonard Westerns. That’s why they’re great, why they last.”

“The biggest problem with genre is that we do feel the divisions very keenly and are aware that science fiction, fantasy and mystery is, by and large, intelligent, thoughtful, far-seeing, and prizes inventiveness and knowledge — but that people generally rate it by its lowest value: orcs, elves, aliens and ray guns.”

The desire for “intellectual hygiene” comes from both sides, says Elizabeth Knox. Knox is perhaps New Zealand’s best-known genre writer, as well as a deeply respected author in the wider literary scene. She’s also one of the most fun people I know to talk about books with. “I’ve come to think of it as a ridiculous mutual exclusion,” she says of the divide between genre and literary fiction. Arguments from both sides can feel like excuses for being lazy. “Literature can appear anywhere,” she says. “In any genre. Good books have life to them. Lots of it. Heyer, Chandler, Tolkien, Elmore Leonard Westerns. That’s why they’re great, why they last.” Knox’s first great success was The Vintner’s Luck, which sold 40,000 copies worldwide in its first year. Her most recent novel, The Absolute Book, has also enjoyed international success, and her style is highly regarded for balancing literary and genre modes. “I’m right in the middle. What they like to call ‘interstitial fiction’,” Knox says. “I wanted to walk that line.” She mentions the thriller writer Lee Child. His Jack Reacher series is looked down on by some, but Knox and I have both read plenty. The protagonist is a great contemporary creation, an incredibly popular character written in an intentionally unaffected way. There’s the bones of Hemingway there, something of Wilbur Smith, a dash of Atticus Finch in Reacher himself, elements of pulp Westerns and slowly unfolding Sherlock Holmes detective stories. “It’s obvious Lee Child loves Reacher,” Knox says. “There’s a weird magic between his know-how and flair which couldn’t be done cold-bloodedly.”

Talking about the writers who move between literary and genre forms (Nabokov, Updike, Le Guin, Iain Banks, Bulgakov, Atwood, Dickens and many, many more) feels like a breath of fresh air, a kind of literary permission. If everyone’s interior mind is a kind of private reality, perhaps speculative fiction is the most appropriate way to question that reality. As Knox says, “being a grown up might just mean changing your mind”.

She mentions a speech she gave at the Aotearoa New Zealand Festival of the Arts in Wellington in 2020, just before the first Covid-19 lockdown. Entitled “Useless Grasses: On Imagination”, it ends: “once again, I come up against the idea that non-realist fiction is childish because it somehow doesn’t represent the world as it is. That idea, that there’s a world as it is — a given, agreed upon, nonnegotiable world. As it is. But what if that world were to disappear? What if it is disappearing? Hastening to change — to turn its spiny, scaled and un-scalable back on us, until it isn’t a world we can climb on and fly away to another world, it won’t let us, it won’t forgive how we failed to imagine it.”

In today’s culture “high” and “low” forms of art are often intentionally mixed, an evolution in mainstream tastes. On white linen, high-end restaurants serve their best fried chicken. Bob Dylan is awarded the Nobel Prize for literature (and doesn’t turn up for the ceremony). Beyonc and Jay-Z film their latest music video in the Louvre, in front of the Mona Lisa. Yet there’s still some lingering reserve over giving genre writing its due.

As a bookseller I’ve sold every shade, original and sequels, of the Fifty Shades of Grey series. Many times over, and usually in discreet paper bags. But this guilty-pleasure-type transaction belies a greater truth. Genre is vastly popular. Its tropes populate almost all modern art, across every medium, from Marvel superhero movies (which let’s not forget started their long life as comic books) to Game of Thrones, Avatar, Dune, Netflix’s recent monster-hit Squid Game and every episode of Inspector Morse. Seen in this light, the idea that genre could be a limit to quality holds little water. It seems short-sighted, even arbitrary.

Perhaps what’s most important is recognising that genre deserves respect on its own terms. That the medium is not the message. Nor is it an index of insight or value. What the many recent genre hits tell us, from Harry Potter to The Hunger Games, is that these books are capable of reflecting society back to us in unique ways while also striking a chord with an enormous number of readers. Their popularity is no accident. Katniss’ sacrifice for her beloved sister, Harry’s bravery in his quest to do good, to vanquish evil — these are stories which reflect back to us how we hope we would act in the face of terrifying adversity. During the years-long run of the TV series Game of Thrones, we could all note the striking parallels between the short-sighted bickering of the various power factions as a much greater menace, the white walkers, threatened to destroy them, and our own global leaders’ seeming inability to face up to climate change. Genre can be doubly innovative in how it employs the rules of its own forms, while still offering the value and messaging of conventionally recognised highbrow art. It should take something less biblical than a flood to acknowledge that a genre writer can explore as widely in the depths and complexities of humanity as any other artist.

Tobias Buck is a contributing writer for North & South. He lives in the Netherlands.