Culture Etc.

On The Gravy Train

Sick of being unable to find a decent pie anywhere in Europe, these Kiwi expats decided to start baking their own.

By Gregor Thompson

Every four months, Natasha Boyer drives to the Centre Comprendre et Parler (the Understanding and Speaking Centre), a non-profit organisation in eastern Brussels that helps hearing impaired children integrate into mainstream education. The centre is currently teaching 600 children to use sign language and how to lip read in both French and Dutch. Boyer, a Belgian native, has been taking her three-year-old daughter Anna, who has a rare hearing disorder, on the regular three-hour round trip since she was six months old.

There is a second important stop to make following each visit to the Comprendre et Parler. After Anna’s check-up, the two will stop for something special to eat on campus at the neighbouring University of Louvain. The last time she was there, an atypically sunny Belgian afternoon in January, Boyer opted for one tourte de berger, a tourte kiwi and two servings of soupe patate-douce. Or, to put it in more familiar terms, one potato-top pie, a mince-and-cheese and two bowls of kūmara soup.

A Belgian university campus sounds like an obscure place to find New Zealand’s favourite guilty pleasure — in fact, Scotty’s NZ Pies is the only place in Belgium where Boyer and her daughter can enjoy this exotic delicacy. When New Zealanders in Europe run into one another, be it by chance, because of a sporting event, or in pursuit of solidarity, the small talk is predictable. Initial pleasantries are routinely followed by impersonal personal questions like “Where are you from?” and “Do you know so-and-so?” Then, invariably, we discuss Europe’s notable absence of decent pies.

Fortunately for those of us who’ve made the 19,000-kilometre journey, pie-loving pioneers like Scotty Roughan have set out to correct the deficit. Roughan grew up in Lawrence on the eastern edge of Central Otago and 40 minutes’ drive from Roxburgh’s famous Jimmy’s Pies, which his family would frequently visit when driving through town. Roughan moved to Brussels 20 years ago and joined the local rugby club to make mates, learn French and integrate. He quickly learnt two lessons. First, Belgians are terrible at rugby. And second, cheese cubes served with mustard and celery salt make a dreadful post-match meal. “I used to see Jimmy’s Pies in my dreams,” he says.

He wasn’t the only one. Since about 2015, a small handful of Kiwi-style bakeries have been popping up in continental Europe. From Amsterdam and Brussels, up to Stockholm and as far east as Krakow, nostalgic antipodeans are finally able to get their hands on a taste of home — and locals like Boyer and Anna are being rewarded for their curiosity.

From Brussels, if you catch a two-hour flight northeast and look hard when you land, you’ll find the Wild Kiwi Pies café and bakery. In Valby, Copenhagen (the municipality home to the original Carlsberg Brewery), Stu Thrush stands at the counter of a small space filled with New Zealand artefacts and cultural references. Portraits of Daniel Carter and Richie McCaw hang from the ceiling; a door labelled “wharepaku” confuses busting Danes; and on the bookshelf Hairy Maclary from Donaldson’s Dairy sits beside Faehunden, a Danish edition of Footrot Flats.

Despite the New Zealand motifs, Tim Tams and L&P, the owner-founder of Wild Kiwi Pies thinks of his business as a Kiwi-run enterprise for Danish people. “The pie is too great for us to cling on to as our own,” Thrush says. His mission isn’t without its challenges. Convincing Europeans to give the pie a go can be tricky. Is it a snack or a meal? Can I eat it while I’m on the go? Should I eat one or two? What if it’s served with a salad? And can I freeze a pie and reheat it? While New Zealanders instinctively know the answers to these questions, until very recently the Danes had never asked them. Over the last six years, however, word-of-mouth recommendations turned Wild Kiwi Pies’ clientele from predominantly expat to majority Danish. “I’d like to think we’re part of the community now.”

When New Zealanders in Europe run into one another the small talk is predictable. “Where are you from?” and “Do you know so-and-so?” Then, invariably, we discuss Europe’s notable absence of decent pies.

In that time, Thrush has stuck his proverbial finger into many pie opportunities. He has his hospitality business, he’s tried street food, he delivers locally, he does wholesale delivery to pubs and cafés, and he’s in the take-home-and-heat-up market. Prior to the pandemic and Covid-19 leaving planes idle in hangars, you could find Thrush’s pies on Norwegian Air flights. At one stage, he was even in talks with IKEA Denmark.

Before opening Wild Kiwi, Thrush had no experience in kitchens. He first moved to Denmark from New Zealand 11 years ago to work for Maersk, the Danish shipping giant. After a decade of climbing the corporate ladder, Thrush realised he’d had enough, “I saw the light. You get to a point when you realise you don’t want your boss’s job.” As a 15-year-old, Thrush had folded boxes for Dad’s Pies, the family operation started in Red Beach in 1981 by industry legend Eddie Grooten; it now supplies Wild Bean Cafes and petrol stations all over New Zealand. With no firm idea of what his next move might be, Thrush gave Grooten a call. The longtime pie entrepreneur told him that, above all, you have to maintain high quality and never cut corners. Thrush now dreams of expanding Wild Kiwi and supplying pies to Denmark’s service stations.

The market Roughan and Thrush have entered was already brimming with competition — Europe has plenty of pie-adjacent analogues. In France, for instance, you’ll find tourtes, which are at least a type of pie. A disappointing one. The meat is typically solid, like a pork pie, and they often come with a hard-boiled egg in the centre — essentially a flat, pastry-enveloped Scotch egg.

Further east again are Russian piroshki, hand-held diminutives of the larger pirog, a much-celebrated pie that comes in various shapes and flavours. The kurnik, for instance, is a dome-shaped pirog filled with chicken, eggs, onions and rice with stars baked on to the exterior. Travel south towards the Balkans and beyond and you’ll encounter pita zeljanica, various types of burek and Greek spanakopita — delicious in their own right but still not quite the same. Turn back west and the Sicilians might offer you sciachiatta, a deliciously literal “pizza-pie”.

Of course, it is the United Kingdom’s pie culture that bears the most resemblance to our own. However, modern British pie innovators have failed to transcend the boundaries that their New Zealand contemporaries have pushed past. Outside of East London, where mincemeat pies and jellied eel remain a working-class staple, the British pie has been restricted to a handful of flavours and is imprisoned in pubs with its partners in crime: peas, gravy and mash. Fish and chip shops in Wales and the north sometimes have pies drying out in their food warmers. Sausage rolls and Cornish pasties dominate the meat-in-pastry market.

Convincing Europeans to give the pie a go can be tricky. Is it a snack or a meal? Can I eat it while I’m on the go? Should I eat one or two? What if it’s served with a salad?

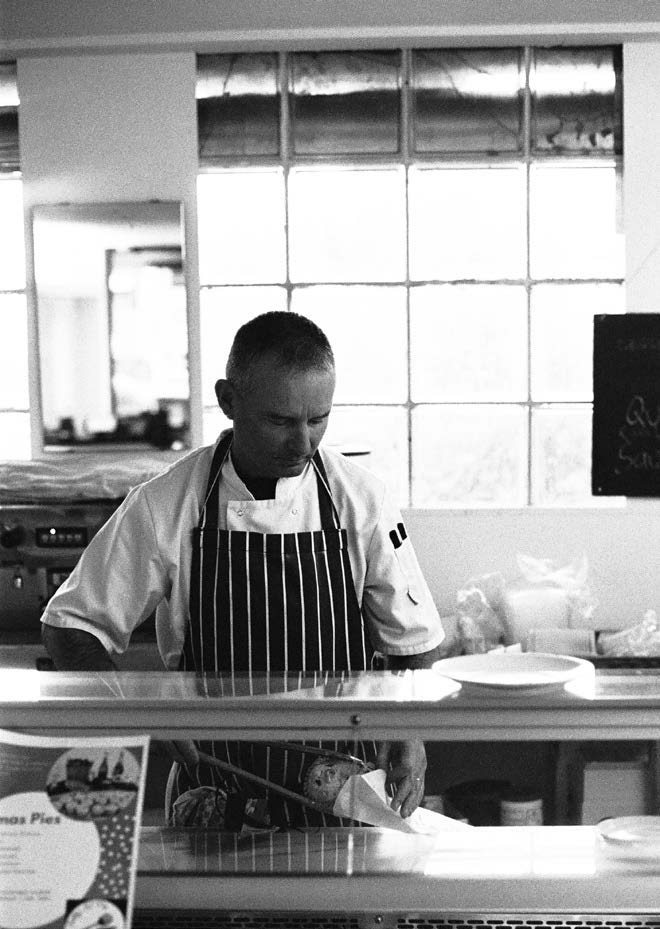

Scotty Roughan started Scotty’s NZ Pies not long after moving to Belgium. Photo: Gregor Thompson.

This is what really sets our pie culture apart: the ubiquitous nature of pies in New Zealand. Not only are bakeries almost as common as dairies, but pie warmers — an appliance scarcely seen in Europe — have turned the dairies themselves into pie dispensaries. Household-name operations like Mrs Mac’s and Irvines are in every freezer in every supermarket in every town large enough to have a Four Square. Pies are in service stations, school canteens and cafés, at birthday parties, in golf clubrooms, aboard aeroplanes and at all major sports events.

This ubiquity is not lost on Tom Simpson, who moved to Sweden in 2011. Like Roughan and Thrush, Simpson felt something missing in his new life abroad. In 2015, he and his wife Victoria started NZ Pies, a retail operation based out of Katrineholm, a town about the size of Levin located 140 kilometres west of Stockholm. Simpson began by subleasing a commercial kitchen and going straight for wholesale, seeing more potential for long-term growth in that market.

Today, NZ Pies has grown from being a local pie business to a national and international one. The little kitchen was soon replaced with a factory. You can buy the Simpsons’ fresh and frozen pies in supermarkets all over Sweden as well as various locations in France, Germany and Finland. Simpson estimates that they and their five full-time employees bake a couple thousand pies every day, seven days a week. “Not going to say we’re Irvines,” he says. “But we’re trying our best to be as big as we can.”

Trying to link Roughan, Thrush and Simpson together in order to make some poetic and humbling observation about Europe and the antipodes isn’t as easy as you might think. They’re three different people, with three different stories. The key similarity is that they were all born in New Zealand, and they all love pies. Perhaps that’s the point. Whether it’s a Tokomaru Bay paua pie, a Roxburgh Jimmy’s mince and cheese, a daily lunch, an embarrassing hangover cure or a gluten-free, vegan pumpkin, mushroom and kale, the New Zealand pie doesn’t discriminate.

The pie is an unglamorous national emblem, one that burns the roof of your mouth and leaves stains on your t-shirt. It might also be the most appropriate. Foreigners know us for The Lord of the Rings, our landscape, our indigenous culture, the All Blacks and our bare feet. We know ourselves for pies.

Back in Brussels, Scotty’s NZ Pies has been hit hard by Covid-19. The university students who were supposed to be his customers are stuck at their respective homes studying from a distance. Inside, to the exasperation of her mother, little Anna spills the soupe patate-douce all over her lap. As she wipes sweet potato off her child’s jeans, Boyer mentions she used to attend the university here before Anna was born. “This was a sandwich shop I used to frequent — I actually first came in here by accident.” She’s pleased with the change, though. “We always eat well here.”

Stu Thrush of Wild Kiwi Pies in Copenhagen. Photo: Gregor Thompson.

Gregor Thompson is a New Zealand writer living in Paris. He likes good food and interesting people.