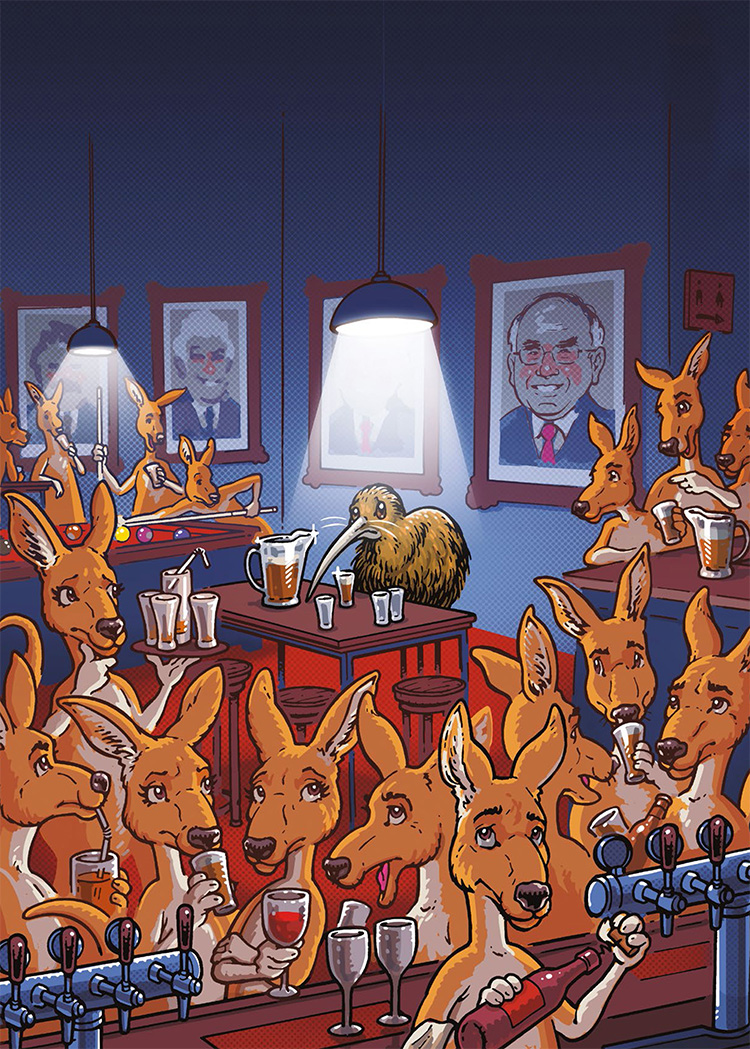

Once Were Mates

We’ve stood together in wartime, been long-time friendly neighbours and enjoyed our sporting rivalries. Many families span both sides of the Tasman Sea. So why did Australia turn sour on New Zealanders? And is there a way back to mateship?

By Pete McKenzie

Illustration by Blair Sayer

In the middle of the red-veined Australian outback, where nothing interrupts the border between sand and sky, a New Zealand journalist watched a snake shed its skin. The transformation appealed to him.

Bernard Lagan had joined Wellington newspaper The Dominion straight out of school. He proved a dogged reporter, moving from the news pages to the press gallery. In the early 1980s he won “Journalist of the Year” at New Zealand’s annual media awards, then moved to Sydney.

In those days the top Australian outlets had enough cash to send enterprising writers across the world. Upon arrival Lagan was offered a spot at the Sydney Morning Herald, which dispatched him to Papua New Guinea to report on rumours of civil war. This was a greater stage than New Zealand, with greater resources: irresistible to a young gun who wanted to prove himself.

Later, he went to Canberra as a political reporter. The capital’s wranglings were intoxicating and exhausting. One weekend, in search of mental and physical space he drove west. He sped past Wagga Wagga and Mungo and Broken Hill, stopping only where the world was silent and the land stretched uninterrupted in every direction.

It was there, sitting on a log, that he saw the snake. “It was such a beautiful thing,” Lagan says. “I just loved this, loved the interior.” When he first came to Australia, he planned to eventually return home to Wellington. As he watched the snake, he realised home was where he had arrived.

Lagan married an Australian journalist, raised two Australian children, and became a chronicler of the Australian experience: he works now as The Times of London’s Australia correspondent. He occasionally visits New Zealand but has no desire to live there. At some point he realised the snake wasn’t the only one that shed its skin. “I really consider myself an Australian more than anything else now,” he says.

“They knew the policy changes would cause hardship,” says longtime resident, journalist Bernard Lagan of welfare cuts. “But they thought, ‘If it’s too hard, go home.’”

Lagan’s experience is not unique. The Australian government estimates that 670,000 New Zealand citizens live in Australia: enough to fill Hobart three times over. Some arrived as children, others as adults. Most embrace an identity split across the Tasman. They include highly skilled professionals, lauded creatives, miners, office workers, menial labourers. They are a blessing to the Lucky Country.

And yet for decades they have been marginalised. Governments motivated by xenophobia and populism withdrew the social safety net, bricked off the path to citizenship, and tossed out thousands of misbehaving Kiwis — even when those deportees had lived all their life in Oz.

These governments knew that, despite ANZAC platitudes and the legendary “mateship” so valued by Aussies, Australians still considered Kiwis to be “others”. They also knew those “others” couldn’t punish them at the polls. So, they ignored New Zealand’s cries that their actions were corrosive to the trans-Tasman brotherhood.

Until July, that is, when Anthony Albanese met Jacinda Ardern in Sydney. Albanese, the freshly elected prime minister of a Labor government that intends to be a “source of pride” to Australians, promised flexibility on deportations, new pathways to citizenship, and an end to Kiwis’ “permanently temporary” status.

Ardern called it a “reset” of the trans-Tasman relationship. Behind it lay personal friendship, diplomatic manoeuvring and electoral calculation. But it is unclear whether the shift will stick. For it to do so, Albanese will need to do more than remain in power. He will need to transform Australian politics.