Before Their Time

Fifty years after a groundbreaking New Zealand discovery that has saved the lives of thousands of premature babies around the world, doctors and scientists are still struggling to reduce inequities in pre-term birth prevention and care.

By Donna Chisholm

Photo: Vanessa Green

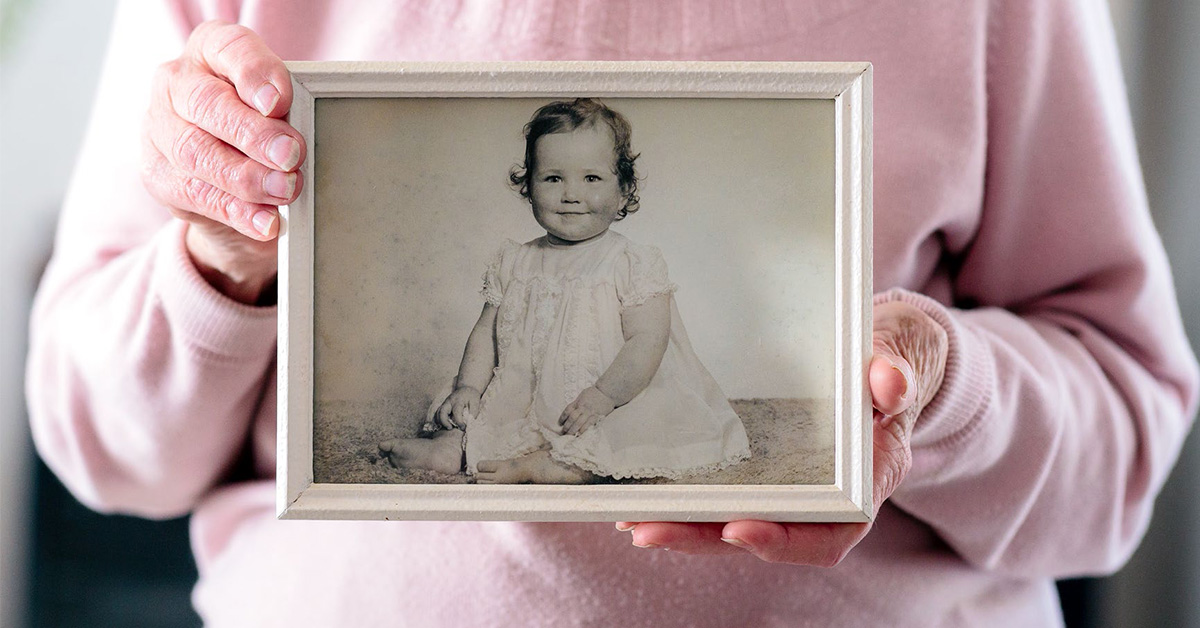

Jeannette Owler’s memories of the terrifying hours and days before her daughter’s birth, way too soon, return now in brief mental snapshots. White-coated doctors prodding her belly. Murmured discussions about slowing the labour . . . somehow. The words “touch and go”.

It was December 1970. Auckland’s National Women’s Hospital neonatal unit, where daughter Lesley was quickly taken after her birth seven weeks early, had just one ventilator. Not only was neonatal medicine in its infancy, but babies born very pre-term usually didn’t even make it to the unit. They died because their lungs were too immature for them to take their first breath.

But all this was about to change, as Lesley and 1200 other premature babies born around this time became part of the groundbreaking trial by Sir Graham “Mont” Liggins and paediatrician Dr Ross Howie to prove that corticosteroids given to the mother before birth could develop their unborn baby’s lungs and save their lives.

Liggins’ discovery, initially in sheep and borne out by the clinical trial, would ultimately change obstetric and neonatal practice globally, although it took many years for the rest of the world to catch on. Liggins and Howie published the results of their study in 1972, but steroid use did not become a mainstream treatment internationally until the late 1990s, apparently because of fears about potential adverse effects.

One of those white-coated doctors working in the neonatal unit when Lesley Owler was treated there was a young house surgeon called Peter Gluckman. Now Distinguished Professor Sir Peter Gluckman, he founded the Liggins Institute in 2001 to carry on that pioneering research, later becoming the inaugural Chief Science Adviser to the Prime Minister.

In the 1990s, he and a group of other influential scientists lobbied, unsuccessfully, to have Mont Liggins awarded the Nobel Prize. “He’s without a doubt our greatest medical scientist,” he says of Liggins, who died in 2010.

Steroids moved the bar for premature baby survival from 36 to 32 weeks. Since then, other techniques have reduced that still further, to around 23–24 weeks. “It opened up modern neonatology,” Gluckman says. “Until Liggins came along, modern neonatology was effectively oxygen and blood exchange transfusions and not much else.

“I was a gopher back then,” he says. “I remember having to ring Ross Howie and say, ‘You’ve got to come in to see this child because it’s in the trial.’”

Until the research was completed, doctors would not know which mothers received a dose of steroids — delivered via injection — and which would become part of the control group who received a placebo. “Somebody would give you an envelope and say this is what the woman will get.”

Indeed, Jeannette Owler found out only as this story was being researched that she was among those who received the steroids. “I was pretty amazed. I feel terribly fortunate and very grateful because it could have gone the other way. When you’re lying there and you have no idea what’s happening and people are prodding and poking at you and you feel sick, you just go with the flow really.”

Daughter Lesley, now Lesley Reeve, had mixed feelings about finally resolving what had been a lifelong mystery. “A part of me had wanted to know,” says Reeve, “but it had been a secret for so long that a childhood part of me wondered whether it should stay that way. Then I realised that knowing it answered a lot of questions and could be useful health information for the future.”

Fifty years after the trial, the Liggins steroid regime remains the gold-standard treatment for babies at risk of premature delivery. But Gluckman and other experts in fetal and neonatal research acknowledge that exactly what determines the timing of birth remains a mystery.

“We don’t know why it is that 280 days after conception, the baby pops out,” says Gluckman. “We don’t know how that clock is really set. There are suspicions it’s set very early in development, but we don’t actually know how that works.” Nor do they know what happens in many pregnancies to reset that clock, meaning babies are born weeks or months too soon. Some causes are recognised — including smoking, maternal high blood pressure and diabetes, problems with the uterus, placenta or cervix, and births in women who are very young or older than 35. Most, however, are not.

Pediatrician Ross Howie (left) and scientist Graham “Mont” Liggins!in the National Women’s Hospital neonatal unit in the early 1970s. It took nearly 30 years for their findings to be adopted globally. Photo courtesy of The Liggins Institute.

Queen Elizabeth met Sir Graham “Mont” Liggins and his wife, Cecelia, Lady Liggins — Auckland’s first female obstetrician and gynaecologist — at the o!cial opening of the Liggins Institute in 2002. The institute was founded by Sir Peter Gluckman and this year, Liggins researcher Dame Jane Harding and her team received the Prime Minister’s Science Prize for 20 years of research on premature babies. Photo courtesy of The Liggins Institute.

Since Liggins and Sir William Liley, who pioneered in-utero blood transfusions for rhesus babies (when the mother’s blood is Rh negative and the baby is Rh positive, maternal antibodies can harm the baby) in the 1960s, New Zealand has remained at the forefront of international neonatology through the work of Dame Jane Harding, the Liggins Institute expert on the treatment of abnormal blood-sugar levels in newborns, and former paediatrician Gluckman, internationally renowned for his research into how a baby’s environment in the womb determines life-long health. Now Liggins researchers are continuing their search for knowledge with those babies from the 1970s.

This year, Auckland mother-of-three Reeve joined more than 400 other participants in a follow-up study at the Liggins Institute to examine whether the babies whose mothers received the steroids are any different at the age of 50 to those who did not. At a 30-year follow-up, the steroid group showed a slightly higher rate of insulin resistance, which can be a pre-cursor to diabetes. The results from the current follow-up will not be known for at least a year.

The trial is part of a number of research projects at the institute which aim to improve outcomes for premature babies, increase consistency in practices at neonatal units nationally, and reduce inequities in access to the best care.

Part of the reason for the inconsistences and inequities, the researchers say, is that despite decades of advances in neonatology, doctors still don’t have the answers to many questions, some as basic as the best way to feed very prem babies.

What they do know is that better pregnancy care is key, pointing to disparate rates of premature births by ethnicity. There are 4500–5000 premature deliveries here annually, which is about 8 per cent of total births. The numbers have remained fairly static — a local win given that pre-term births are on the rise globally. The rate of early deliveries is higher for Maori (9 per cent), Indian (8.8) and Pacific (8.1) women, and lower for European (7.1) and Asian women excluding those of Indian descent (7.3).

“We’ve definitely got differences by ethnicity,” says maternal fetal medicine specialist Associate Professor Katie Groom, who leads several Liggins Institute research projects. “Our ethnic group is not our risk factor for pre-term birth, it’s all the things that ethnicity gives us or doesn’t give us. And that’s frustrating, because when I think, ‘What can we do from a medical perspective?’ Socioeconomic status, racism, and these types of things contribute way more than the actual medical stuff.”

One of the most basic steps is for women to book pregnancy care with a midwife or hospital in the first trimester, but again, rates vary by ethnicity, with around 60–65 per cent of Pacific women booking then compared with 85–90 per cent of European women.

“From the get-go, Pacific women are behind, because we’re not finding out what’s going on, what are their health conditions, how can we optimise their health?” says Groom. “It’s easy to say, ‘I don’t know what the right dose of steroid is.’ But I think we’re tinkering at the top end. We really need to look at all the pregnancy care we provide, and how we can do better.”

Improving equity and consistency in pre-term care is one of the aims of the Carosika Project — Taonga Tuku Iho which Groom established in 2019 and co-chairs with South Auckland mother Tina Allen- Mokaraka, the mother of baby Carosika, who died an hour after her birth in 2014, at 23 weeks and six days gestation, when Allen-Mokaraka was 20 and her partner Tasi Wilson was 18.

“The Carosika Project’s overarching principle is achieving equity in a culturally responsive way,” says Groom. “We want the research and the work we do to be consumer-led and consumer-focused. For Maori and Pacific it’s not to do with their ethnicity, it is all the confounders associated with that. Poorer health, socioeconomic factors, poor diet, lack of engagement with a midwife in the first trimester . . . it’s a spiral and we want to look at the inequities of it and see how we can support change in pregnancy.”

According to statistics from the Perinatal Maternal Mortality Review Committee report, Maori, Pacific and Indian women are more likely to have their babies born extremely early and less likely to have their babies resuscitated when they’re born.

The potential impact of the critical midwifery shortage is “a ticking time bomb,” says Groom. “It’s just a bit scary to be honest.”

Tina Allen-Mokaraka and Tasi Wilson’s daughter, Carosika died shortly after her premature birth. They now help with research as part of the Carosika Project. Photo: Jason Oxenham, NZME.

Tina Allen-Mokaraka, who now has two school-aged children, contacted Groom in 2018 after reading the story of another woman’s premature birth at about the same gestation. Her baby survived after the mother was given treatment to slow her contractions, steroids to mature the baby’s lungs and delayed clamping of the umbilical cord to allow the baby to receive more stem cell-rich blood from the placenta.

Allen-Mokaraka arrived at hospital too late in labour to delay the delivery. Carosika was born just over an hour after they were taken to hospital by ambulance and Allen-Mokaraka chose for her not to be actively resuscitated after doctors told her the baby would probably not survive and risked being brain-damaged. She had also been traumatised by the death of her own older sister in an intensive care unit two years earlier.

Her involvement with the Carosika Project has eased much of the guilt surrounding her decisions, Allen-Mokaraka says. “I had thought I had made the wrong decision not to give her a chance and that she had deserved that chance.”

In the Carosika Project, representatives of 55 groups nationwide, including midwives, obstetricians and gynaecologists and the Ministry of Health are joining forces to produce a best-practice guide covering all aspects of pre-term birth care. They have reviewed current guidelines which were adopted ad hoc by the now defunct district health boards. It will, says Groom, bring the best of them together to provide a resource aimed at improving consistency and equity in care “wherever you live and whoever you are”. It will specifically consider ethnic, geographical and other social needs.

Groom is leading a New Zealand and Australian study investigating whether the Liggins steroid regime could also benefit the babies of women who have later-pre-term births, after 35 weeks, and before a caesarean section birth.

“It’s the next big question in the use of corticosteroids,” says Groom. It’s early days — so far only 370 babies have been enrolled in the “C*STEROID Trial”, which aims to study 2500 — and progress has been hampered by Covid and a shortage of clinical staff able to support the research.

Because the chances of a baby having breathing problems reduces with each week it remains in the womb, the issue after 35 weeks is more focused on risk and benefit.

Also vitally important in the care of prem babies — indeed all newborns — are blood-sugar levels. Dame Jane Harding and her team were”this year awarded the Prime Minister’s Science Prize for 20 years of work investigating blood-glucose levels in babies: How should they be monitored, how do they affect a child’s development and what should be done if they’re abnormal? About 30 per cent of newborns have low blood-sugar levels, which can cause brain damage and have also been linked with cot death. Babies who are small or large for their gestational age are also at higher risk of low blood sugars.

In the womb, babies have had a constant supply of the glucose that their brain needs for energy, but once the umbilical cord is clamped, the sugar levels drop and premature babies have more trouble getting them back to normal.

From left to right, Katie Groom, Frank Bloomfield, Stuart Dalziel. Photos courtesy of The Liggins Institute.

In 2013, Harding’s team showed that a $2 sugar gel rubbed inside the baby’s cheek effectively treats low blood sugar levels and helps to keep babies out of intensive care. Conversely, she says, four out of five very premature babies (those born at less than 28 weeks), particularly the smallest and sickest, have high blood-glucose levels, which are associated with infection, brain haemorrhage, poor growth and death. “But all these things are also associated with being very small and very sick, so it’s difficult to work out which is actually the cause.”

How best to feed premature babies once they reach the neonatal unit is still not well understood, with a study led by Liggins director Professor Frank Bloomfield in 2020 finding variations in practice around neonatal units both here and in Australia.

“This is the most basic, simple thing you can do — feeding — and we don’t know how to do it correctly for these babies,” says Bloomfield. “The burning question for me is should we be using additives in nutrition to try to promote growth or does that not have any benefit and just causes adverse effects?” Attempting to boost protein intake, for example, can cause serious metabolic abnormalities known as “refeeding syndrome”.

“Different feeding is related to different outcomes but what we can’t say yet is whether there’s a causal link between the two. Different hospitals have different rates of metabolic disturbance linked to the way the babies are fed. We know metabolic disturbance is linked to poor outcome and that poor outcomes differ around the country. Because there is little good-quality evidence about what the standard way to feed pre-term babies should be, everyone does what they think is best.”

Poor nutrition in mothers is associated with an increased risk of premature birth. “The evidence we have – again, it’s not the strongest evidence — suggests women who are dieting around the time they conceive, that that might lead to an increased risk of pre-term birth.”

Japan, for example, is the only high-income developed country in the world where birth weight is decreasing rather than increasing, and pre-term birth is also increasing. “It’s also one of the only countries in the world where a woman’s BMI around late adolescence and early 20s doesn’t increase as it would normally with the hormonal changes that take place. It’s a societal thing. They are dieting.”

And being even a few weeks’ early, while not life-threatening, has ramifications. “The brain of a baby born at 35 weeks, only five weeks early, is only two-thirds the size it is at term so there is a massive amount of growth in that last five weeks.”

Growing recognition of the importance of those last few weeks is one of the reasons why truly elective caesarean deliveries at 38 weeks — once so common they were known colloquially as being “too posh to push” — have practically disappeared.

For University of Auckland Cure Kids Professor of Child Health Stuart Dalziel, a member of the steering group on the 50-year follow-up of the Liggins babies, the latest study is a compelling conclusion to the research he began 20 years ago as a PhD student. He was one of five people who tracked down 700 of the by then 30-somethings — mainly through electoral rolls.

“In the basement at National Women’s they had an index card record, with mother’s name and when the baby was delivered and we could match that up. It took about 10 hours for each baby, but some took far more than that. A massive, massive effort.” He says a few of the 30-somethings who’d moved overseas even came home to take part — at the behest of their mums.

“You’d go to mothers who had no idea if they received the placebo or the steroid and they’d say, ‘Yes, Mont Liggins and Ross Howie saved your life, so you’re coming home to New Zealand for 10 days and you’re going to go and see these people.’ We didn’t pay to get them back but there was an awful lot of goodwill. That’s why we got such an incredibly good response rate.”

Today, Jeannette Owler, 84, and her husband Clifford, 91, still live in the same Howick home they were in when Lesley was born. Jeannette can’t recall consenting to take part in the Liggins trial — “I was in too much of a state” — but Dalziel says the records of the day show the trial received ethics committee approval and mothers gave verbal consent which is recorded in their notes.

Harding says it’s unsurprising that women might not remember giving their consent. Not only were women stressed and anxious, but Harding says for the first few years of the trial, which ran from 1969, the drug used to try to slow labour was actually intravenous alcohol. “It was the best they had at the time.”

It was a harrowing time for the anxious father, too. Clifford Owler remembers holding 4lb baby Lesley in the palm of one hand. She had, he says, “a body similar to a seriously underweight rabbit”.

“I saw mum through the glass and she looked as if she’d been in a road accident. I fainted and the nurse got me a cup of tea.”

Fifty years on, Lesley Reeve is excited to be still involved in the ongoing research. It seems deeply ironic that two of her three children were delivered after their due dates, in one case by emergency caesarean.

Reeve, says until this year, when she took part in the 50-year study, she hadn’t fully grasped the enduring impact of Liggins’ work — and didn’t know about the research institute that had been named in his honour. But she’d always been proud of her involvement in the trial. “I nearly died. They told my father that I might not live. I’ve been really excited about being part of this trial all my life. It was my cool thing.”

But, she says, it’s also bittersweet. “I’m so grateful I was one of the babies whose mother received the steroids. But I also wonder about the babies who were possibly lost because their mums did not.”

Lesley Reeve, pictured with her parents Cli!ord and Jeannette, is now 52, and says the chance to be involved throughout her life with the Liggins research has been “my cool thing”. Photo by Vanessa Green.

Donna Chisholm is an award-winning journalist based in Auckland.

This story appeared in the December 2022 issue of North & South.