Lost in the Weeds

After a century of prohibition, it’s now legal to buy cannabis medications from pharmacies. But most doctors won’t prescribe it, the black market is still flourishing and despite local companies raising more than $100 million to grow it, it’s almost entirely imported from overseas. What’s gone wrong with what was meant to be a booming sector?

By George Driver

Photo courtesy: Rua Bioscience

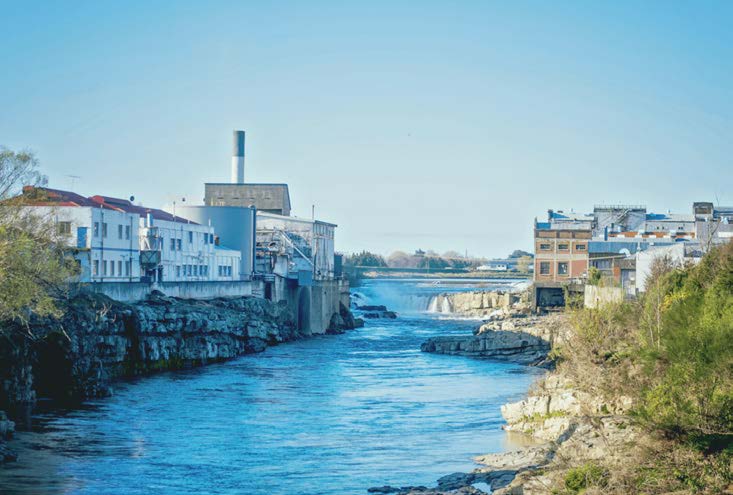

It was once one of the most controversial and dangerous buildings in the country. Now it’s filled with cannabis.

When the Mataura paper mill opened in the 1870s it was the first of its kind in New Zealand, offering new promise for a fledgling settlement on the Southland plains. At its peak, more than 200 people worked at the factory, beside a waterfall on the Mataura River, about 10 kilometres south of Gore. But when international competition caused the price of paper to plummet in the late 1990s, the mill finally closed. The last Mataura-made paper left the factory in 2000 and the enormous buildings sat vacant.

Then a new business came to town. A Bahrainiowned company called Taha Asia Pacific saw potential in Mataura. In 2015, it reached a commercial agreement with the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter to store about 10,000 tonnes of the smelter’s toxic waste in the old mill. It was meant to be temporary, but when Taha went into liquidation in 2016, the waste became Mataura’s problem. Eventually it drove the inhabitants from their homes. When the waste — Ouvea premix, a byproduct from aluminium dross — gets wet it releases toxic ammonia gas. In 2020, during a record flood, the Mataura River almost inundated the mill. The town was evacuated due to the threat of toxic gas and the country watched and wondered how such a potential environmental catastrophe was able to occur. The last of the dross was finally removed in 2021 after an agreement between government and the smelter and things looked to be returning to normal. Then another business arrived into Mataura.

When the government passed a law to legalise prescription cannabis, or “medical marijuana”, in December 2018, a new industry was seeded. The Misuse of Drugs (Medicinal Cannabis) Amendment Act gave the government the power to set standards for medicinal cannabis products and rules for the new industry. It also removed cannabidiol (CBD) as a controlled drug, instead making it a prescription-only medicine (often available as an oil). Unlike tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the cannabinoid largely responsible for the plant’s psychological effects — the “high” — CBD is considered non-psychoactive but is touted as a potential anti-anxiety and anti-inflammatory drug.

The law change also introduced a defence for palliative care patients using cannabis, effectively decriminalising the drug for the terminally ill (cannabis remains illegal for everyone else, unless they have a prescription).

In 2018, the first licences were granted for companies to cultivate medicinal cannabis for research purposes ahead of the new regime and dozens of companies gained licences around the country. By 2020, cannabis was finally able to be legally grown medicinally around the country and cannabis oils and even cannabis flowers (often colloquially known as “buds”) became available at pharmacies on prescription. A new industry based on a plant that had been outlawed for almost 100 years began to emerge. Southern Medicinal, now based in Mataura’s old mill is one of them.

In a sparsely furnished room in a prefab building that served as the mill’s testing lab, Southern Medicinal co-owner Greg Marshall explains how the industrial building will become a major employer once more. Marshall says when the business reaches full production there will be about 300 people employed in the factory, processing 250 tonnes of cannabis a year grown on 500 hectares of farmland around the country, and under lights inside the mill’s warehouses. A further 800 will be employed planting and harvesting the crop.

Marshall says that for Southern Medicinal, the main attraction in Mataura is power. The paper mill has its own hydro power station, and the biggest expense for an indoor cannabis operation is electricity. In 2019, Marshall started the company with the owner of the building and power station, Greg Paterson, brother of the late richlister Howard Paterson and one of the wealthiest landowners in the South Island, and Dunedin businessman Paul Chamberlain, who is CEO of the mental health charity, PACT Group. Marshall has a background in finance and cannabis. He was a founding director of North American cannabis company, Cannex, now trading as 4Front Ventures, all while based in Otago. He remains a shareholder of the company which operates in five states in the US, producing about 32 tonnes of cannabis a year. Marshall claims Southern Medicinal will be able to produce indoor-grown cannabis flower — where the highest concentrations of cannabinoids reside — at a cost of less than a dollar a gram, one-20th of the current street price. “We plan to be the first example of medicinal cannabis disrupting the black market on price,” Marshall says.

He walks me outside, into the drizzle and brisk southerly of a southern spring, through a high-security gate in a barbed-wire fence and into a foyer of the old warehouse next door. Here we put on white overalls, booties and hairnets, then enter a low-ceilinged room which looks vaguely surgical — a white painted concrete floor, stainless steel implements on stainless steel tables and blinding lights. In five containers, dozens of cannabis plants stretch up towards LED lights, their nutrients carefully controlled via a hydroponic drip below. They are being grown to produce high concentrations of THC.

Through another door we enter the cold, cavernous warehouse of the paper mill, where about 40,000 cannabis plants carpet the floor, illuminated by bright lights in an otherwise gloomy room which was recently filled with toxic dross. These strains are low in THC but high in CBD. In a few weeks these plants will be travelling around the country, destined for 15 farms, including 10 in Southland, in what Marshall believes will be a major money-maker for farmers. In autumn, the plants will be harvested, processed back in Mataura and turned into a CBD concentrate both for export and for Kiwi patients.

But at the moment, that’s purely theoretical. So far, the business has had one outdoor cannabis harvest, processing 10,000 plants and several tonnes of cannabis flower. But almost all of it has then been shredded and composted. Inside a container in the mill sit sacks containing hundreds of kilos of high-THC cannabis flower. If it was sold in a pharmacy today it would be worth millions of dollars, but at the moment Marshall’s products have been unable to meet the government’s minimum quality standards and this too is destined for the compost heap. It’s currently the fate of almost all of the tonnes of cannabis grown by licensed companies around the country.”

When the government took the first steps to legalise medicinal cannabis in 2017, there was talk of it becoming the country’s next big export sector — that Kiwi-grown weed could be the next sauvignon blanc. Companies around the country raised over a hundred million dollars, often from mum-and-dad investors through crowd-funding platforms like PledgeMe, and the government has likewise poured millions of dollars into getting the sector established.”

But in the two and a half years since the medicinal cannabis scheme came into force, no locally grown cannabis flower has been approved for sale in New Zealand so far, and only two CBD oils made from Kiwi-grown cannabis, produced by a single company, have received the Medsafe tick. The rest of the more than 20 products available are imported, or made locally from imported cannabinoids.

While the companies wait for regulatory change, or innovations that will allow them to pass the stringent tests, they are spending millions keeping the high-tech lights glowing to grow thousands of cannabis plants that may be destroyed. “We’re bleeding out,” Marshall says.

Mataura’s economic fate has depended on its two main industries bordering the Mataura River — the meat works (left) and the paper mill (right). Photo courtesy: Southern Medical

Above, Greg Marshall’s business involves partnering with dozens farmers to grow tens of thousands of cannabis plants on farmland around the country. Photo: George Driver

A ROYAL CURE

While cannabis is the latest class of medicine available for prescription in New Zealand, it is one of the oldest medications in the world, and was available over the counter here until the 1920s.

Humans have been using cannabis medicinally for at least 5000 years, but possibly much longer. Its first recorded use is in a Chinese pharmacopoeia from 2800BC. In the West, hemp — a leggy cultivar of cannabis sativa that has low levels of THC — was widely grown as a source of fibre, but the plant’s medicinal use doesn’t appear to have been widespread. That changed in the 1800s. Irish physician Sir William Brooke O’Shaughnessy worked in hospitals in India in the 1830s and noted that locals used cannabis oil to treat pain and spasticity. He brought the higher THC “Indian hemp” back to England in the 1840s, where it appears to have gained widespread acclaim. It is claimed Queen Victoria used cannabis tea to relieve menstrual cramps and the Queen’s doctor, Sir John Russell Reynolds, later called the plant “one of the most valuable medicines we possess”.

Cannabis concoctions soon found their way to the colonies. In New Zealand, ads began appearing in newspapers for Chlorodyne in the 1860s. It contained a potent mixture of chloroform, morphine, laudanum and cannabis and was marketed as a wonder drug to treat everything from coughs and colds to cancer and cholera. An ad published in the New Zealander in 1861 includes an endorsement from a surgeon who was using “20-drop doses with marvellous good effects in allaying inveterate sickness in advanced pregnancy”.

Grimault and Co’s “Indian Cigarettes” were also advertised here, “prepared with the Essence of Canabis Indica” [sic] and used for “asthma, and other complaints of the respiratory organs”. In the 1880s, “Dr Douglas’ Maori Cigarettes” containing cannabis, hemlock and datura, were also promoted as a cure for bronchial conditions. According to the national encyclopaedia, Te Ara, cannabis cigarettes were sold as a treatment for asthma and bronchitis until the 1930s.

Cannabis wasn’t regulated in New Zealand until 1927, when it was scheduled in the Dangerous Drugs Act after an international convention called for its control. Cannabis could still be imported or manufactured under licence and was available by prescription. Medicinal cannabis use, however, was reportedly declining in any case as it was eclipsed by opiates and aspirin, which were more consistent and easier to dose.

In the 1960s, the world lurched further towards prohibiting the plant. The 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs made cannabis a schedule IV drug, reserved for the most dangerous drugs whose “liability is not offset by substantial therapeutic advantages”. In New Zealand, this eventually led to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 which classified the cannabis plant as a Class C drug, with a moderate risk of harm, along with codeine, Valium and ketamine. If you possess or supply these drugs you face a maximum of three months imprisonment (although judges are advised not to impose prison sentences for possession and supply unless there are exceptional circumstances or previous convictions).

Like other controlled drugs, since 1975 cannabis was illegal to possess, manufacture or supply, but it was still able to be prescribed. But unlike Valium and morphine, which have been approved by Medsafe, prescription cannabis required ministerial approval. In practice this wasn’t forthcoming. The first Medsafe-approved cannabis medicine, a THC mouth spray called Sativex, wasn’t available in New Zealand until 2010 and was only approved for multiple sclerosis patients when other treatments failed. The medicine was not funded by Pharmac and reportedly cost around $1000 a bottle.

CBD was even more tightly controlled. A CBD medicine was first approved in 2015 in a one-off exemption involving a teen in a coma who was suffering seizures and later died. The then-health minister Peter Dunne made clear this exemption would not set a precedent.

The following year, medicinal cannabis went mainstream as it was revealed a trifecta of famous and respected Kiwis — broadcaster Paul Holmes, cricketer Martin Crowe and union leader Helen Kelly — had all used cannabis medicinally while battling terminal cancer. Kelly, suffering lung cancer, applied to the Ministry of Health via her oncologist to use a cannabis oil medication for pain and nausea. Her application was denied. In 2017, even a Grey Power branch lobbied for the government to legalise medicinal cannabis and in June that year, Dunne announced CBD products would be able to be prescribed without ministerial approval.

The watershed moment, however, occurred during the 2017 election campaign. A month after becoming Labour leader, Jacinda Ardern was asked during a leaders debate whether the party would legalise medicinal cannabis if elected. Ardern told debate host Mike Hosking, “I don’t need 30 seconds, the answer is absolutely yes.””

Seven weeks later, Labour took office in coalition with New Zealand First, and within 100 days the Misuse of Drugs (Medicinal Cannabis) Amendment Bill was tabled in Parliament. A year later, it passed (National opposed it, calling it decriminalisation by stealth). It gave the government a year to develop minimum standards for products and rules around prescriptions. A transition period, however, meant CBD products could be imported and sold without approval until September 2021 and products soon became widely available. Cannabis vaporisers were also legalised if they had been approved overseas as a medical device. A new industry began to emerge.

GREEN FIELDS OF HOPE

In Ruatoria, on the East Coast, the winds of”change signalled hope. In 2018, the Hikurangi Cannabis Company became the first licensed cannabis company in the country.

Founded out of charitable trust, Hikurangi Enterprises, and run by locals Panapa Ehau and Manu Caddie, it quickly became the face of the medicinal cannabis industry.

Working with those who had grown cannabis illegally in the bush on the East Coast for decades, its founders said it aimed to offer well-paid jobs in a region where there were few opportunities beyond farming and forestry. They told the New York Times they wanted to generate 100 jobs within two years and ensure Maori were able to share in the economic gains of the nascent industry — particularly given they had disproportionately shouldered the burdens of prohibition.”

Their vision gained widespread buy-in on the coast. In 2018, the company raised more than $1 million during a roadshow in Tairāwhiti and later launched a campaign on crowd-funding site PledgeMe which crashed the website due to the level of interest, raising a further $2 million in a single day. In an accompanying investment memorandum, the company forecast a net profit of $4.8 million in 2020, the first year the medicinal cannabis scheme would be operational, paying a $3.18 million dividend to shareholders.”

The local tech institute, the Eastern Institute of Technology, got on board, starting a cannabis cultivation course which attracted hundreds of applicants. Prime-time TV got involved, covering the business’s rise in a six-part documentary, Growing Dope, which aired on Prime in 2021. In 2019, the company changed its name to Rua Bioscience and the following year it became the second cannabis company to list on the New Zealand stock exchange — and the only NZX listed company in Tairāwhiti — with an implied market capitalisation of $70 million.

The hype wasn’t limited to the East Coast. In South Auckland, a company called Helius started up and soon became the country’s largest cannabis company, eventually attracting more than $50 million in private investment, including $15 million from richlister Guy Haddleton. Founded by advertising executive Paul Manning and local entrepreneurs Gavin Pook and JP Schmidt in 2018, Helius presented the clean-shaven, besuited and pharmaceutical side of the industry — a contrast to Rua’s dreadlocked, flax-roots approach.

The government, meanwhile, has ploughed around $18 million into the industry. The largest grant occurred in April last year, when it gave $13 million to Marlborough cannabis company, Puro, to produce a handbook on growing organic cannabis and to develop unique cultivars — Puro also committed $19 million to the project. Agriculture minister Damien O’Connor said it was to support regional job growth in the Covid-19 recovery and that cannabis could become as successful as the wine industry.

When the rules for the scheme were finally released in April 2020 — just a week into the country’s first Covid-19 lockdown — they included what have been called the toughest standards in the world. The regulations set a pharmaceutical standard for medicinal cannabis, requiring the rigour and consistency of a paracetamol tablet, but for a plant prone to natural variability. To manufacture medicinal cannabis — whether that’s drying cannabis flower or manufacturing THC or CBD oil — companies must get a Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) certification, the gold standard for producing pharmaceuticals. This requires extraordinarily thorough procedures and expensive equipment. Some in the industry claim it’s impossible to meet the standards without spending tens of millions. So far only four NZ cannabis companies have received GMP certification: Rua Bioscience, Helius, Katikati company Eqalis and Tauranga-based ZHM.

Once GMP certified, each product must then undergo thorough testing before it’s approved for prescription. Products must be shown to have consistent potency and shelf life and low microbial contamination to guard against mould. Many of the tests can’t be performed in New Zealand and can take many months and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. So far, the standards have proved insurmountable for most companies, who have found it almost impossible for a plant to achieve this pharmaceutical consistency. Only one locally grown product has been approved so far, a CBD oil produced by Helius from cannabis grown by Puro.

Rua Bioscience has an approved CBD oil, but this is manufactured using imported active ingredients, not from its locally grown cannabis. Ehau says using their own plants has proved too expensive and the process of getting approval is too challenging. “It takes anywhere up to 18 months to get one product verified, so our first priority has been about getting product out to New Zealanders and unfortunately the quickest way is by importing it,” Ehau says.

Panapa Ehau says the cannabis industry has failed to provide the economic boon that was hoped for, but has still created new jobs.

The regulatory barriers have hit the company’s share price. When Rua listed on the NZX in October 2020 — just a week after the recreational cannabis referendum failed — it reached 70 cents a share. It’s mostly been downhill since — as of November it was trading at $0.245. The company is yet to turn a profit. In the 2022 financial year it reported an $8.6 million loss, up from a $6.19 million loss the previous year. In fact none of the medicinal cannabis companies growing in New Zealand have been profitable yet and many are haemorrhaging millions a year, with revenue so far elusive.

GreenFern Industries in Taranaki claims to have achieved what no one else has, by growing a cannabis flower that passes the test regime, but it likely won’t be available to New Zealand patients — at least not for some time. The company doesn’t have a GMP licence and so plans to export its flower to Europe to be processed in facilities that do, and sell the product there. Managing Director Dan Casey says it has to focus on making revenue first and can’t afford to invest in getting GMP certification yet. “We’ve got investors breathing down our necks wanting results and at the moment the lowest hanging fruit is overseas markets.”

The company has raised $8 million and listed on the NZX in October 2021, peaking that day at a share price of $0.43, but has since declined to $0.094. In 2020, it forecast it would make $7.9 million in revenue in the 2022 financial year and $28.8 million in 2023. But as of June 2022, it recorded a $2 million loss for the year. Its main source of revenue has been buying CBD oil in Australia and repackaging it for sale there under the GreenFern brand.

Because of the high costs of setting up, all of New Zealand’s cannabis companies are dependent on exports — primarily to Australia and Germany. But despite many having lucrative supply agreements on paper, so far none have achieved this on a commercial scale. Even though the products won’t be consumed in New Zealand, they still have to meet our standards to get an export licence. The products then also have to meet the destination country’s standards, leading to costly double testing which can take many months. And most companies still can’t surmount the first hurdle of local approval.

Rua has now changed tack. In January last year, it bought Zalm Therapeutics, a cannabis company chaired by former Air New Zealand CEO Rob Fyfe, for $10 million. Zalm has an agreement with Cann Group, one of Australia’s largest cannabis companies which has a AUD$120 million growing and processing facility in Mildura, in Victoria, capable of producing 12,500 kilograms of cannabis a year. For the foreseeable future, Rua’s cannabis will be grown in Australia for export to Germany, although the company says there may be some locally grown products available soon.

Ehau explains that the Ruatoria site will remain a breeding programme for now, supplying the genetics to be grown in Australia. He says Australia’s regulations are less restrictive, while the industry has been established there for longer and is more developed. Medicinal cannabis was legalised there in 2016. Ehua says it might not be viable to export from New Zealand on a large commercial scale. “It’s really expensive to grow in New Zealand,” he says. “Our grower model was to enable people who have grown in the illicit market to come into the light and not have to look over their shoulders — the people who have carried the knowledge of the plant for decades in New Zealand and carried the negative implications of it being illegal. But the reality is it’s really expensive compared to other places in the world.”

Ehau says Rua may be able to produce small quantities for niche markets from New Zealand, but mostly its products available here will be grown in Australia: not quite the vision the company started with. It employs about 20 people locally, down from a peak of about 30. But Ehau still says the venture has been worthwhile.

“The cannabis company was never meant to be a shiny knight riding a white horse and saving the day,” he says. “It was only supposed to be one thing that contributed to increasing wellbeing and I know there have been wins. We’re still able to develop intergenerational knowledge and capacity and we have a number of people employed in pharmaceutical jobs that haven’t existed before.”

In Mataura, Greg Marshall wants to export cannabis flower to GMP facilities in Australia and the US, but the products haven’t passed the loss-on-drying test, designed to ensure the plant material is dried sufficiently so it won’t encourage mould growth. He says the standard is impossible to meet and is calling for a different testing regime to be used, but Medsafe says this will require Cabinet approval which hasn’t been forthcoming.

Southern Medicinal’s ultimate goal is to produce a product called rosin, a cannabis extract created without solvents by using pressure and heat — what he says will be the Central Otago pinot noir of New Zealand cannabis. However, currently he is required to have a GMP certification to do this and he says the cost would make the operation unviable. Marshall says in Australia he would be able to produce the rosin and sell it without GMP, provided the final stage of production was carried out in a GMP facility. But in New Zealand GMP is required at each stage of production, which he says is prohibitively expensive. “All this does is add costs without improving patient safety,” Marshall says. “It fundamentally impacts the viability of the industry.”

Article continues after..

WHERE THERE’S SMOKE . . .

There’s grey area in New Zealand’s drug laws when it comes to cannabis. It is illegal to possess or grow cannabis: it has effectively only been decriminalised for the terminally ill and is legal for those with a prescription. But generally, small amounts for personal consumption may evade the long arm of the law. Since 2019, the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 states “prosecution should not be brought unless it is required in the public interest . . . [and] consideration should be given to whether a health-centred or therapeutic approach would be more beneficial”. The act also advises judges not to impose prison sentences for possession and supply unless there are exceptional circumstances or previous convictions. These changes have sometimes been interpreted as decriminalisation, however cannabis remains both a Class C and Class B drug, depending on how the plant is used.

Cannabis preparations including hashish (the resin of the plant, rich in THC) and cannabis oils, and technically covering cannabis cookies and other edible forms of cannabis, are classified as Class B, with a “high risk”. Other Class B drugs include MDMA (ecstasy), amphetamine (speed), morphine and fentanyl (a drug associated with more than 50,000 overdose deaths in the US in 2020 alone). Making or supplying these drugs attracts a maximum 14 years imprisonment and three months for possession. However, cannabis is a Class C drug when it’s in basic plant form (cannabis flower or “buds”), the same classification as codeine, Valium and ketamine. Possessing these drugs attracts a three month maximum prison sentence and eight years for dealing. Cultivating cannabis is a separate offence with a maximum seven-year sentence.

It’s also illegal to possess drug utensils for consuming cannabis, including a bong, pipe or “roach clip” used for holding a joint — the latter is defined as a device with “a pincer or tweezer action” that “depicts cannabis fruit, cannabis seed, or any part of the cannabis plant”. Possession of one of these tweezers carries a maximum sentence of one year in prison. Cannabis vaporisers are now legal, though, provided they’ve been approved overseas as a medical device.

Cannabis prosecutions continue. In 2021, 2578 people were charged for cannabis offences, half of which were for possession or utensils and eight per cent of those charged with cannabis-only offences were sentenced to prison. Only 13 per cent of those convicted were for possession-only offences, and prosecutions are declining.

Article continues…

A couple of companies have already failed. Last year, Rotorua cannabis company MedGreen Pharmaceutical, one of the country’s first, went out of business after it reportedly ran into cash flow problems. The owners attempted to sell the business as a going concern, but there were no takers and it was later sold out of administration . Another, Medicann based in Tauranga, went under in 2020 after shareholders voted to liquidate the company when one of its founders allegedly misled investors.

Ali Seyfoddin, an associate professor in pharmacy at the Auckland University of Technology, started a postgraduate course on the science of cannabis in 2020, attracting 100 students in its first semester. He says the high cost of producing pharmaceutical-grade cannabis means most companies might not be viable long-term.

“You’ve created an exclusive market where only big players with millions of dollars of investment can survive,” Seyfoddin says. “I really don’t see this industry going forward if they keep the current legislation. In two years’ time there might be two companies left, the rest will be bankrupt.”

Six years ago, Mark Dye had a small business importing “fish hooks and lip balm”. Now he imports kilos of cannabis. Photo courtesy: Mark Dye

LICENSED TO SELL

The only cannabis companies that appear to be making money are the importers. Mark Dye founded NUBU Pharmaceuticals after a life-changing four hours at his day job, hosting afternoons at radio station, Newstalk ZB. It was shortly after the death of Paul Holmes and Martin Crowe when the topic turned to medicinal cannabis and something remarkable happened. “We had four hours of positive talkback,” Dye recalls. The station’s largely conservative listenership was unanimously calling for legalising weed. “I thought, if the older generation are calling out for this then the politicians are behind.”

He began working on a business plan while hosting reality TV show, Heartbreak Island. Initially, Dye planned to start a cannabis growing company like the others, but after looking at businesses overseas he changed tack and focused on importing cannabis. “We realised there were thousands of people building these facilities globally and New Zealand was too late to the party.”

It took 15 months to get the first product approved, a cannabis flower grown by Australian Natural Therapeutics Group (ANTG) in a small town in New South Wales. Last year it became the first cannabis flower to be legally sold in New Zealand in a century. The cannabis flower from Australia has been able to meet New Zealand’s regulations by irradiating the product to kill microbes — the microbial limit test is one of the main barriers to getting products approved here. But the irradiating equipment costs millions of dollars. New Zealand growers have said they’re reluctant to irradiate their product and are exploring alternatives.

Having jumped the hurdles, Dye is supportive of the stringent regulations. “As frustrating as the process was and the amount of sleepless nights it caused, I understand it. This is a medicine that is going to be ingested by people and needs to be safe.”

Medleaf Therapeutics also started importing cannabis flower from Canada and Australia and has two products approved. The company was founded by Courtney Letica, who began illegally growing cannabis in his garage in 2016 to help his uncle who had terminal cancer and had been denied legal access. “I made him an oil and it helped him sincerely,” Letica says.

The company’s sole employee, Shane Le Brun, has been a patient advocate for medicinal cannabis for more than a decade. He also grew the plant illegally to help his wife who suffered from chronic pain from a spinal injury. Le Brun went on to become coordinator of Medical Cannabis Awareness, a charity helping patients navigate legal access.

Le Brun and Letica say other countries are able to grow cannabis at a far cheaper price, making the medicine more affordable for New Zealand patients. The company is currently seeking approval to import from a Columbian grower.

“New Zealand patients aren’t wealthy,” Le Brun says. “They are often on a sickness benefit, so there’s no room to have a premium price for a premium product. It’s a medicine. Would people pay more for a packet of paracetamol because it’s made in New Zealand?”

Overseas companies are also playing a greater role in the New Zealand market. Australian cannabis company MedReleaf now has three cannabis flower products approved while American pharmaceutical company Tilray has five approved products.

Ali Seyfoddin agrees that there’s little opportunity for New Zealand exports. “There’s nothing unique about New Zealand cannabis,” he says. “It’s mostly from imported seeds grown in controlled environments, so there is no export market. As soon as America federally legalises cannabis they will be exporting it. Colombia and Mexico are exporting and Thailand is coming up too. We’ve missed the train.”

Unlike sauvignon blanc, it is difficult to market pharmaceutical products based on New Zealand’s brand. Because cannabis is an unapproved medicine, it is illegal for companies to advertise and in practice that has prevented them from providing any information about their products here. They can only provide information once a doctor or pharmacist requests it directly. Companies also can’t export to recreational markets as a UN convention bans this. But the cannabis companies say they do have a competitive advantage and a future.

Carmen Doran took over as CEO of Helius in 2021 after working for 10 years in senior positions at the global pharmaceutical giant, Novartis. She says New Zealand is viewed as a country with trusted institutions and regulations, which is important when selling medicine, particularly in a global industry where many companies aren’t used to pharmaceutical regulations. “We can’t compete on price, but we can on innovation and quality.” She says the future will be around developing cannabis strains and products designed to target specific medical conditions by using precision growing techniques and innovative delivery systems.

Despite the stringent regulations, most companies North & South spoke to were supportive of the pharmaceutical standard. “It’s medicine, it’s got to be something that’s not going to make people sicker,” Doran says. Germany already requires GMP-grade cannabis, while Australia is moving to GMP regulations, so relaxing restrictions might make exports unattainable, and New Zealand companies can’t survive on domestic sales alone. But many in the industry claim New Zealand follows a stricter interpretation of the rules than anyone else. They all want tweaks, particularly around enabling local testing and relaxing rules to allow for exports to be allowed without meeting local standards. “Some restrictions can be changed without impacting patient safety,” Doran says.

The industry would also like to see low-dose CBD products available over-the-counter, as is the case in the United Kingdom and parts of Europe, and for government subsidies for medicinal cannabis products to make them cheaper for patients. Greg Marshall, however, is threatening to take the government to court if the regulations aren’t amended to harmonise with Australia’s rules.

Medsafe declined an interview request but is consulting on changes to the scheme, with submissions due by the end of January. Changes could include allowing cannabis to be exported without meeting New Zealand’s minimum standards and no longer requiring cannabis used in manufacturing oils to be processed in a GMP facility.

MEDICAL BARRIERS

While the cannabis industry is struggling with new regulations, many in the medical establishment are calling for tougher standards.

Product standards are strict, but New Zealand’s cannabis prescription rules are among the most liberal in the world. When the medicinal cannabis amendment was passed, politicians were eager to frame it as being about helping the terminally ill and those with chronic pain. But when the details of the scheme were released they allowed any doctor to prescribe cannabis for any condition.

General practitioners, however, have been hesitant to prescribe the drug because cannabis is unlike any other prescription medicine in the country. Beyond the fact that it’s a plant and many people chose to smoke this medicine, cannabis also hasn’t been approved by Medsafe because there’s not yet enough evidence from clinical trials that it actually works. There is also limited clinical information on the impact of different doses, delivery methods and drug interactions.

University of Otago pharmacology professor Michelle Glass has been studying cannabinoids for 25 years. She says the lack of research is partly due to the years of prohibition. Of the trials that have been completed, she says many are poor quality, with small sample sizes and weak design. Many variables are involved: different doses, the range of cannabinoids (more than 100 have been identified), and different forms and delivery methods. “It makes it very hard to get a clear picture on whether it’s effective.”

The Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand (BPAC), a not-for-profit that gives advice to health professionals, has put out a guide on medicinal cannabis. It says: “There is currently insufficient clinical trial evidence to support medicinal cannabis products being used first-line for any indication.” But it says there may be a case for prescribing for some conditions when conventional treatments have failed.”

Because of the lack of trials showing efficacy, cannabis products are still officially “unapproved” by Medsafe but are available under an exemption created for political reasons due to the high level of public support for legal access — some surveys have found 81 per cent in favour.”

It’s a position the medical establishment has opposed. Both the now defunct New Zealand Medical Association and the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP) called for cannabis products to only be approved if they met the same Medsafe standards as any other medicine. RNZCGP medical director Dr Bryan Betty says because the drug doesn’t have Medsafe approval, many GPs are concerned they may be liable for any adverse reactions. The Medical Council’s Good Prescribing Practice code states prescribers must be familiar with adverse effects, drug interaction, doses and effectiveness of the medicines they prescribe. But for medicinal cannabis, this information is lacking. “If issues were to emerge down the track then there could be legal implications with that,” Betty says. “There’s no doubt that potentially there could be benefit shown for certain medical conditions. But there is a need for good quality trial evidence and good monitoring of potential problems arising.” At a minimum, the college would like to see information recorded on cannabis prescriptions and the demographic of those accessing the drug.

The lack of trial evidence also places the onus on GPs to educate themselves on the risks and benefits of cannabis and Betty says for many — during a pandemic with unprecedented pressure on the sector — it’s been put in the too-hard basket. The RNZCGP is developing a position statement on medicinal cannabis, but Betty says it’s challenging as there is a wide range of opinion among the college’s 5500 members.

Green Doctors owner Dr Mark Hotu says cannabis isn’t a silver bullet, but many people experience significant benefits, especially when conventional treatments fail. Photo courtesy: Mark Hotu

Massey University drug-policy researcher Marta Rychert has led a project evaluating the medicinal cannabis scheme, and has conducted surveys which found patients were being turned down for cannabis prescriptions two-thirds of the time. The biggest reason for doctors denying a prescription was the lack of evidence, but also concerns about their professional reputation and the financial impact on patients. While opiates may be subsidised and cost only a few dollars for a prescription, medicinal cannabis typically costs over $200 depending on the product.

But that hasn’t stopped people accessing cannabis medicinally, albeit in a form that’s completely unregulated. Analysis by the Drug Foundation found an estimated 266,700 New Zealanders used cannabis medicinally, but only six per cent had accessed it under the medicinal cannabis scheme in 2020. While prescription numbers have increased since then, the overwhelming majority appear to still use the black market.

As of September, 76,897 medicinal cannabis products have been supplied under the scheme since January 2021. Of those, 70 per cent were CBD-only products and eight per cent were THC-only, with the remainder being “mixed”. The figures have been variable but slowly increasing, from 2053 in January 2021 to 3632 in September 2021, and a high of 6415 products distributed in August 2022.

Because of the hesitance from some GPs, a number of specialty cannabis clinics have sprung up around the country. People can even get a consultation online and have their prescription delivered to them.”

Dr Mark Hotu started Green Doctors in Ponsonby in 2019 after working as a GP in Auckland and discovering a lot of his patients were using cannabis to treat chronic pain. He began researching the drug and decided to open the clinic, which has grown to have five doctors seeing about 120 patients a week. “The last few months has been the biggest growth in three years,” Hotu says. “There’s been a real explosion.”

Anecdotally, people have also been using cannabis clinics to access cannabis recreationally. Hotu says it is no different to people lying to get other prescription medications. Prescribing cannabis at least gives a level of oversight. “We’re here to help people with their symptoms, not get people high,” Hotu says. “I guess if someone wanted to pull the wool over your eyes they could, but they could do the same thing with sleeping tablets or morphine.”

Other advocates in the profession have said the relatively low risk from cannabis and the potential benefits warrant an experimental approach to prescribing. There has never been a reported fatal overdose from cannabis, making it technically less toxic than paracetamol (although not necessarily less harmful). By contrast, between 2017 and 2021, prescription medicines were involved in 321 overdose deaths, including 97 involving diazepam (Valium) and 72 involving the sleeping pill, zopiclone. In 2021 alone there were 75 opioid overdose deaths and 25 from benzodiazepines.

Hotu says there needs to be more information to educate GPs and he disagrees with the BPAC guidelines. “I don’t think any of them [BPAC] have worked as a physician in a medicinal cannabis clinic. They’re just a bunch of scientists that have read a bunch of articles with no consideration of anecdotal evidence.”

However, Michelle Glass says anecdotal evidence is not science, given that about a quarter of patients in clinical trials report an effect from placebos. “I think we owe it to patients to do proper clinical trials with standardised products and establish whether there is a benefit or not.”

Glass has also been concerned about the proliferation of cannabis clinics, particularly due to the fact that a cannabis company has now opened one. The Pain Clinic, which opened in Nelson in July, is a subsidiary of Medical Kiwi, a Nelson-based cannabis company. Its website says it was established “to meet the growing need for CBD oil and medicinal marijuana in New Zealand”. Other cannabis companies are also opening clinics. “If we had opioid manufacturers setting up doctors to prescribe opiates sponsored by opioid companies we’d be outraged,” Glass says.

A PATIENT WAITING GAME

Five years ago, Pearl Schomburg made a suicide pact. Suffering pain from arthritis and a range of other health conditions, she had been on a concoction of opioids and antidepressants for years when she decided she would either have a life without pharmaceuticals or no life at all. She threw her medications out and started using cannabis butter to treat her arthritis and pain.

“Within 24 hours I felt the fog in my brain lifting and knew I’d made the right decision.”

She has been using cannabis medicinally ever since, sourced from a trusted “green fairy” who goes by “Gandalf”. The well-spoken great-grandmother became a vocal advocate for legalising medicinal cannabis, leading the Auckland Patients Group which marched down Queen Street calling for legalisation in 2017, and has become a facilitator, connecting green fairies with patients in the city.

“My quality of life now is so much improved,” she says. “It’s not that I don’t have pain and discomfort but I can manage it and I know which way I’ll continue for the rest of my life. I have quite a distrust of pharmaceuticals because of my journey.”

Last year, however, she went back to the pharmacy. In February, she became the first person in New Zealand to be legally prescribed cannabis flower. But since then she’s reverted to the black market, or what she calls the “local cannabis market”. She says the imported legal cannabis flower is lower quality and more expensive than what Gandalf supplies.

Cannabis companies are unable to advertise the prices of their products, but information collated by patients online shows the price of cannabis flower ranging from $450 for 35 grams ($12.85 a gram) up to $415 for 10 grams ($41.50 a gram) for a high THC flower. By contrast, Schomburg says the price for an ounce of cannabis in Auckland is $350 to $400 ($12.36 to $14.13 a gram), while a gram of cannabis, sold as a “tinny”, is typically $20. Legal CBD oil ranges from $80 up to $490 depending on the strength and volume and is usually less than $4 for a 50 milligram dose, while THC oil costs around $200 a bottle equating to about $2 for a 5 milligram dose. Because it is difficult for patients to shop around due to the ban on advertising, there is also a huge difference in prices between different pharmacies, with some charging $150 more for the same product.

There are other costs accessing legal cannabis, too. Because most GPs won’t prescribe it, many patients choose to go to cannabis clinics where consultations aren’t subsidised and can cost between $49 and $290. “These can be insurmountable hurdles for people on low incomes and most prefer to grow their own and make what they need,” Schomburg says.

The lack of information available on the legal products makes it difficult for patients to choose different cannabis strains, which Schomburg says can have vastly different effects.

Pearl Schomburg says many cannabis patients have become disillusioned with the legal scheme and prefer to use the black market.

There are, of course, quality issues in the “local market” as well. In 2021, Crown research institute Environmental Science and Research (ESR) tested 100 cannabis products from green fairies and the results were hugely variable. One CBD oil contained more THC than CBD, making it potentially dangerous for some users, and in general products touted as being high in CBD often were not. It found few of the CBD oils and tinctures would provide an effective dose as they had such low levels of CBD.

Schomburg, however, says a legal and regulated “local market” would solve these problems.!She wants food-grade medicinal cannabis to be approved, which would allow green fairies to be registered and provide tested products, without requiring!millions of dollars to meet pharmaceutical standards. She also wants medicinal cannabis decriminalised, allowing patients to grow their own but with a legal testing scheme. “We believe we are the biggest stakeholders in this area but the narrative has been taken over by these corporates and we’re not being listened to.”

Back in Mataura, the cannabis seedlings grown in the mill have now been planted in farms around the country. But Greg Marshall’s not sure whether it will be the last harvest processed in the town, or if the cannabis is destined for pharmacies or the compost heap. He says the company can survive until the second half of the year, when he hopes new regulations will be introduced. “It will be a close run,” he says.

Up the road in Milton, Mike Breeze owns the small cannabis company, Pure Isolation, run out of a converted farm shed. He’s more upbeat. He says for an industry that was outlawed for a century and is operating under regulations that were developed within a year, things are going alright. Breeze got into growing cannabis after growing peonies commercially on his lifestyle block and says the two industries aren’t so different.

“It’s the same as the peony game here,” Breeze says. “We can’t compete on the world stage, but we can together. We collaborate and can fulfil a 30,000 flower order into Holland in a way we can’t do individually and we’re seeing that spirit in medicinal cannabis already and it’s incredibly encouraging.

“I’ve never been poorer or worked harder. We’re all struggling as a nascent industry during a pandemic, but there’s an amazing collaborative spirit that feels uniquely New Zealand. Some interesting approaches and partnerships are emerging and that’s how we’ll win.”

George Driver is North & South’s South Island correspondent. This role is made possible by support from NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.

This story appeared in the February 2023 issue of North & South.