A Country Practice

As the number of general practitioners dwindles thanks to low numbers of new graduates and an ageing workforce, New Zealand faces a major medical crisis — a crisis which has already arrived in high-needs rural areas like the Hokianga, where a lack of doctors has seen vital services closed for months. How did we get here — and what can we do to fix it?

By Findlay Buchanan

Photos by Nina Oxley Wood

Out in the grassy back section of Rawene Hospital in Hokianga, old patient documents have been shredded and turned into mulch. Jessie McVeagh, the hospital’s gardener, picks mint, parsley, kale and green beans from the garden’s raised beds, which have been banged together using recycled timber from the old hospital building (work on a 25-year-long upgrade was completed in 2019). The crops help feed patients at the 26-bed hospital. “Bare grass does nothing for anyone,” McVeagh says.

Opened in 1928, this hospital in Rawene is the heart of the Māori health provider Hauora Hokianga, a not-for- profit, community-owned and governed network of health services delivered across the Hokianga in Northland. It is run by the Hokianga Enterprise Trust, the majority of whose 20-odd members are elected by the community it serves.

In old photographs the hospital’s sprawling grounds are shown primly mowed, with tall Australian oaks framing the edges. Today, native bush is being restored across the grounds, and the Trust has plans to extend the initial plantings of their ara rongoā hikoi whakaora (a literal “healing pathway”) as part of the hospital’s Taumata Rongoā service. This traditional Māori health practice, the first of its kind in Aotearoa, has been rolling out in stages at the hospital since its launch in 2020. It will serve a population which is 80 per cent Māori.

In some way, growing food and restoring nature are small acts of resilience against the pressures staff at the hospital face, not least of which is the shortage of medical professionals including doctors, nurses and St John emergency volunteers willing to come and work in this remote district of Northland. The shortage is a national issue — currently, the country is experiencing a scarcity of general practitioners so severe that some patients are travelling for hours to see a doctor for a 15-minute appointment — but it’s felt particularly keenly in rural areas: one Kaikohe GP interviewed last year about the problem said he had 2000 patients on his books. We have roughly 74 GPs for every 100,000 people — nearly half the rate of Australia, which has 122 GPs for 100,000 people. In November last year, a government-commissioned review into the sector estimated that high-need general practices would require a funding increase of 231 per cent to function properly.

To maintain a homegrown general practice workforce, at least half of each year’s medical graduates would need to become a GP — far more than the roughly 30 per cent who currently choose to do so. Dr Kyle Eggleton, associate dean of rural health and medicine at the University of Auckland’s School of Medicine, says of that group, only a tiny proportion decide to work in rural areas.

Hokianga’s vast beauty runs parallel to a population suffering some of the worst levels of poverty and social deprivation in the country: 96 per cent Hauora Haukianga’s registered patients are considered “high needs” when it comes to primary healthcare. With fewer doctors willing to take posts in rural areas, medical services are being reduced in a town that desperately needs them. In August last year, Rawene Hospital paused its after-hours emergency service as it didn’t have enough doctors to fill its rosters overnight. This means that outside the hours of 8am to 5pm, patients are forced to travel at least an hour further, to either Kawakawa or Kaitaia, to reach after-hours healthcare.”

The impact of this has been severe — in one case North & South was told about by locals and hospital staff, a young child who had become trapped beneath the wheels of a moving trailer arrived at the hospital after 5pm. With no doctor on site, nurses kept the child alive, coordinating with a doctor in a main city hospital via Telehealth while waiting almost four hours for the Westpac helicopter to arrive.

Jessie McVeagh tends to the Hauora Hokianga Hospital gardens at Rawene Hospital. In the background her sister Hebe can be seen weed-eating the lawn.

Hauora Hokianga chief executive and former chief nursing officer at the Ministry of Health Margareth Broodkoorn (Ngāpuhi, Dutch) was born in Rawene Hospital 55 years ago. She says the decision to temporarily reduce the after-hours emergency service was a long time coming, with both doctors and nurses working an unsustainable amount of overtime. “There is a balance of wanting the continuity of service, but not wanting to burn the candle. I had to say to the staff, ‘I don’t want this place to be the end of you’.”

As well as managing the emergency care service and the holistic Taumata Rongoā programme, Hauora Hokianga looks after the primary care of more than 7500 registered patients and runs outpatient clinics and home visits, offers rest-home care and serves as the base for district nursing services. Rawene Hospital provides accident and urgent care for the whole of the Hokianga (including x-rays and resetting broken bones, and a 10-bed acute care service). The hospital also has a maternity unit. For difficult births or intensive surgery, patients must be taken about two hours by road to Whangārei Hospital.”The hospital also serves as a marae, a place for pōwhiri and hui, an education facility and a meeting place for the community. Hauora Hokianga is easily the largest employer in the Hokianga, with some 200 staff on its books.”

Access to emergency healthcare is already a challenge in Hokianga, a region sliced through by rivers and metal roads, where slips and tidal floods often shut off entire settlements, ambulances get bogged in swampy farmland and houses are often without a legible street address. As one nurse puts it: “By the time emergency services arrive it is often too late.”

Hauora Hokianga has been advertising for a general practitioner since early last year, offering competitive pay and free accommodation, but despite entreaties to “come and live in paradise ”, in January the town was still waiting.

Dr Clare Ward notes that times have changed since she arrived in the Hokianga as a locum back in the 1990s. “It wasn’t always easy to get doctors, but we didn’t have real shortages like we have experienced in the last 10 years. It’s definitely the worst it has been.”

Ward, like others who trickled in during the 90s, came to work in the Hokianga to be part of a caring community. Ward wears her hair in a silver bob and has a contemplative smile. People know her as “Dr Clare”, and as we talk people often stop to chat. When she first arrived, Ward recalls being put up on her own board and batten house with sabbatical leave and paid holiday time — real perks compared to what she’d experienced in the city. “I thought it was amazing when I first came here. It was a perfect job and in many ways it still is.”

She recalls being attracted to the style of medical practice offered at the hospital, an approach which can be traced back to the 1940s, when Hokianga was designated a “Special Medical Area” by government. This initiative sought to improve access to healthcare in Aotearoa’s poorest, most remote communities, such as Tairāwhiti and parts of the South Island’s West Coast.

Today, members of the community enrolled with Hauora Hokianga get their healthcare and prescriptions without paying extra fees. It’s what another Rawene doctor, Stephen Main, hails as “the crucible of social medicine”. The free health service is not a luxury, but the only way many people in this high-needs community are able to access healthcare. With patients who suffer disproportionately from complex illnesses like rheumatic fever, meningitis and gout, consultations are typically longer than the standard 15 minutes allocated to GP appointments. Follow-ups are frequent and the relationship between doctor and patient is deep, Ward says. “You get one person who comes in with a splinter in their finger, then after a quarter of an hour, the real questions start to happen.”

Like many of New Zealand’s rural doctors, Ward hovers at the edge of retirement. She’d planned to finish up last year, but was persuaded to stay on part time until vacancies are filled. With the hospital having a slim roster of only seven doctors, when someone goes on leave or retires the loss can be enough to destabilise an entire service. “When I went on extended leave, everyone was already stretched. I do feel responsible, but the service can’t rely on people like me.” The challenge is to attract young doctors in search of a different kind of life, Ward reckons. “Something rural, something challenging, something fun.”

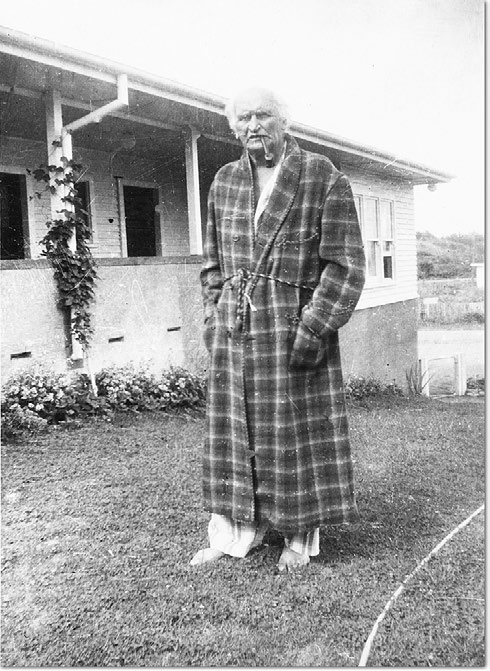

There is no one more illustrative of the attitudes required for rural general practice than the legendary (in some ways notorious) medical superintendent Dr George McCall Smith, who arrived on the shores of Hokianga in 1914. Having left his wife and four children back in Scotland, Smith was travelling to rural Aotearoa with one of his patients, a woman named Lucy Margaret Scott, whom he later married (he also trained her to work as his anaesthetist).”

Smith, who had gained his medical qualifications in Edinburgh, strolled sandal-shod above political convention to fashion his own brand of country medicine. A tall and striking man, he was often pictured with a pipe hanging out of his mouth and was known for his informal manner of dress.

He used cod-liver oil and Vaseline to treat wounds, constructed a homemade anaesthesia device by attaching a modified mask to a rubber bladder, and pioneered “twilight sleep” — alternatively known as “painless childbirth” — by spooning handsome doses of Nembutal (a sedative which is also used for assisted suicide and capital punishment by lethal injection) into the mouths of women giving birth.!While we might look askance at some of these measures today, Smith wasn’t a total renegade and much of his medical knowledge was sound. During the 1918 outbreak of Spanish flu, he imposed a type of lockdown in the Hokianga, closing shops and posting armed men at crossroads, as well as organising teams to feed the sick — measures which proved effective at reducing the spread of the epidemic. He was also progressive for the time in promoting the importance of nurses, and earned the respect of Māori despite some suspicion at the time about Pākehā medicine. He died in 1958 at the age of 76.

While the archetypal “backblocks doctor” might be a distant memory now, in 2008 rural medicine became its own specialty in Aotearoa. Since then, both the Auckland and Otago medical schools have offered a variety of placement programmes to seed a new crop of rural GPs. The initiatives have had varying levels of success.

Dr George Marshall McCall Smith, pictured here in later life, was a legendary backblocks doctor who, despite behaving in some ways like a bit of a renegade, was nevertheless a well-respected and highly capable medical practitioner.

In the case of the Hokianga, the Pūkawakawa programme in coordination with Whangārei Hospital offers fifth-year medical students a seven-week opportunity to live in Rawene and work at Hauora Hokianga. Though many students value the experience and gain valuable skills, a gap of at least three years follows for further study and hospital placements before they can begin to train as a rural GP.

In that time attitudes toward rural life may blur into memory, dimmed by eight years of student debt, families to wrangle and the attraction of higher-decile schools and the perception of more attractive amenities in the cities (at least one doctor interested in the Hauora Hokianga GP role pulled out because they weren’t happy with the childcare options available in the region).

Eggleton says the placements offered to medical students are helping, but the full effects of their impact aren’t being felt yet.!“It will take 15 years before we start to see the benefits of these programmes,” he says. “Unfortunately, we signalled 15 years ago this will be a problem, but successive governments haven’t done anything to try and improve the issue.”

Increased specialisation, which has become more common in New Zealand in recent decades, has also had an impact on the number of medical students interested in pursuing work as a GP. At medical school, the more vocational work of general practice is always seen as the “poor brother”, Ward says. “It’s always seen as an inferior branch of medicine where only women who want to have families or people who didn’t have much ambition or ability would go into general practice.”

Certainly, the shift from the do-it-yourself medical generalism of Smith’s era to the situation today in which nearly all surgical practice is reserved for centralised hospitals has contributed to rural hospitals being left without the resources or skills to offer their communities local specialist care.

Of course, one surgeon booting around the Hokianga with a leather doctor’s bag is not nearly as safe or efficient for the patient as travelling to the nearest orthopaedic surgeon for a knee replacement, or cardiologist to deal with heart problems, but in many ways working at Hauora Hokianga still demands a certain dose of Smith’s medical philosophy. This is particularly true for Hauora Hokianga’s district nurses, who travel great lengths to care for their 7500 registered patients on home visits. (Not to mention unregistered patients — one old poem speaks of a Hokianga nurse “Plunketing a new born pig” with teat and bottle as part of her community rounds.)

The Hauora Hokianga network extends beyond the hospital to the hills and valleys around the harbour, with 10 community clinics spread from the southern blocks of Taheke to the northern shores of Pawarenga. The clinics, generally former housing for nurses in timber or brick, are carefully placed across settlements to ensure fair access to them. Now the patients can visit their nurse or doctor once or twice a week at these sites, surrounded by bright flowers, ramshackle gardens and wandering animals.

Like the district nurses who operate them, the clinics do not have a strictly medical, institutional vibe. They feel like community centres — a warm and humane place for whānau to access healthcare, pick up prescriptions, kōrero and collect kai. Most importantly, though, they are often the only operational medical buildings for miles.

“Without them, people wouldn’t get healthcare,” says Hauora Hokianga district nurse Donna Leef-Dunn (Te Rarawa). “It’s as simple as that. Even with the clinics, it can be hard to access patients in need.” Dunn, who has worked in the Hokianga as a rural nurse for more than 10 years, divides her time between the Broadwood and Pawarenga clinics.

The role of district nurse here is all-encompassing. When needed, Leef-Dunn acts as a Plunket nurse, a palliative care nurse, a temporary doctor (in the case of emergencies when no trained doctor is available), a social worker who advocates for better housing in the community, a counsellor to patients with various degrees of trauma and a health promoter at schools and educational facilities. She’s also a bloody good driver.

When Leef-Dunn isn’t at the clinic, she criss-crosses the district visiting patients. The roads are gravel, the hills foreboding and the corners notoriously blind and sharp. A home visit could include a tide-dependent trip to Rangi Point, a shoulder-high river crossing on the stretch out to Pawarenga, or a backcountry climb up the western ridges of Panguru.

Leef-Dunn remembers when she misjudged a river crossing and her car began to float downstream.“I was ready to jump out the window and swim, water was coming in through the windows. All the stuff in the back seat was floating.” Leef-Dunn laughs and points to a rock to show how far she had drifted — at least 50 metres away — before her car hit something hard and she managed to surge out just in time.

Another night, Leef-Dunn received a call from her husband, who farms in Panguru, about a colleague who needed CPR but was isolated on 4000 acres of rolling hills. “It was a rough and stormy night,” she recalls. “We called a helicopter but it couldn’t come due to the weather. They sent an ambulance, but the ambulance couldn’t get to them, so I had to horse ride up to the top of the hill to help assist.”

By the time Leef-Dunn found her patient, she says, it was too late. “They were in the middle of nowhere. Horses were thigh-deep in mud. It was horrible for everyone. People do die.”

During a typical day, Leef-Dunn may visit only three or four homes, but the impact of her work is immense. She drives down a main road where dogs run across the gravel edges and a wash of high tide slides in through the mangroves. “We’re dropping off some drugs,” she tells me as the car turns into the driveway of a home chequered with dogs, toys and rusting cars. After she’s made the delivery, Dunn points out the windows and doors she recently secured for the family in coordination with an iwi organisation in Kaitaia, which assesses substandard living conditions in Northland and help to provide people with basic amenities like water tanks and windows.

Dunn knows the roads, the people and the environment, and the way she draws on this knowledge in her work strengthens the fibre of the health service, in which social welfare, housing and health are interwoven. Most critical to her job as a district nurse is the trust she builds over time by visiting people in their homes, under all conditions and circumstances. It goes beyond health, she says, it’s about relationships. People don’t always welcome a nurse showing up at the door — Dunn recalls one family telling her to “fuck off and get the fuck away”.“Then you’d see them in other community settings and they’d get used to you. Next thing you know you’d see them at the clinic, then you might be allowed in their house — sometimes that can take a few years. But it’s what you have to do.”

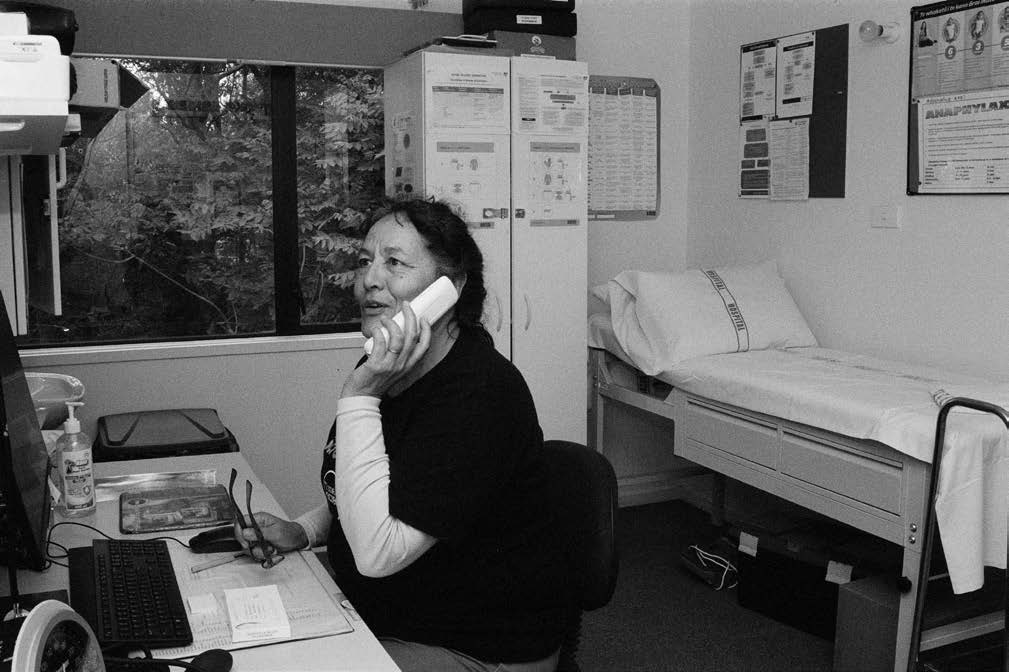

Community nurse Donna Leef-Dunn makes a follow-up call to a patient in the Pawarenga Clinic.

Nurses like Leef-Dunn are in as short a supply as GPs; shortages permeate the entire workforce, including aged-care workers. If the country has a metaphorical national noticeboard for job vacancies, next to the “help wanted” ads for rural GPs are desperate pleas for nurse practitioners.

In the face of this struggle, the government plans to spend $14 million dollars on a recruitment service to help attract international nurses and doctors to the sector — international workers already make up 40 per cent of Aotearoa’s medical workforce.

While many international health workers successfully embed into their communities, Auckland med school’s Kyle Eggleton notes, for every three international graduates, two will leave after just one year, typically to Australia where the pay is higher.

Eggleton says change needs to happen locally by increasing the number of medical school students; Auckland currently admits about 257 domestic students a year and Otago 282. “We need to increase graduation numbers. For next year, universities could increase their intake of medical students by 50 total.” Eggleton also cites an Australian model where student placements are tagged to rural training, delivered across independent rural clinic schools, to provide better pathways into rural health. Sixty per cent of those students go on to work rurally.

For the community of Hokianga, as the days drift on without their 24/7 emergency service, many in the community fear for themselves, their whānau and the health of their community hospital. Rob Shadbolt, who lives in Kohukohu and volunteers on Fridays at the St Mary’s op shop, says like many in the community he was saddened when he learnt about the hospital suspending its 24/7 emergency service. It’s such a vital service to lose, he says. “It’s obvious everybody is going flat out at the hospital. Everybody is putting 110 per cent into their jobs, they are really busting their gut, but they do such an incredible job.”

Meanwhile, with the consolidation of district health boards into Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand and the Māori Health Authority, many of Hauora Hokianga’s health contracts are up in the air. The organisation stood at a similar crossroad back in 1991 when a new National government prepared to slash health funding and disband area health boards.

Although it’s unlikely Hauora Hokianga will foot a hīkoi to Parliament like locals threatened to in 1991, few are excited about climbing aboard one big ship. “I’m still waiting for Mr Little to come and visit,” quips Broodkoorn about the then-health minister. “It was great when the prime minister came last year to visit. Jacinda put her gumboots on and brought her entourage — it was great to be able to show her what we do in Hokianga.” Now, perhaps, they may need to invite the new Prime Minister Chris Hipkins and Little’s replacement, Dr Ayesha Verrall.

Broodkoorn says the key is for rural areas like Hokianga, Tairāwhiti and the West Coast to be higher up the agenda. “Funding needs to be allocated according to rural health. All contracts need to take into account not just the salary but the overheads which are inclusive of a rural adjuster, such as a nurse going on a 1.5 hour home visit, or the need for nurses to have a four-wheel-drive vehicle.”

As part of the health system reforms, between 60 and 80 local health networks are being set up across the country to replace the local input of the old DHBs. These “localities” aim to connect community voices with both Health NZ and the Māori Health Authority. Yet, despite it having a very high needs population, it remains unclear whether Hokianga will be a “locality” or not.

Broodkoorn says she is excited about the stated intent of listening to the specific needs of the local community, but reiterates that conversations should be driven by that same community rather than dictated from above. “Localities are about how we bring in all the social determinants of health and work together to determine what we need,” she says. “It’s not for providers to determine, it’s about working with the community to determine the priorities.”

Her message is not dissimilar to a call from Smith in the 1945 pamphlet Plans, Plots and Appraisals from the Backblocks (later republished in a 2010 history of health in the Hokianga): “What do we want? — what we need, what is ours. That’s all! We want to use our own share by our own social security contributions, for our own social security needs, and in our own way.”

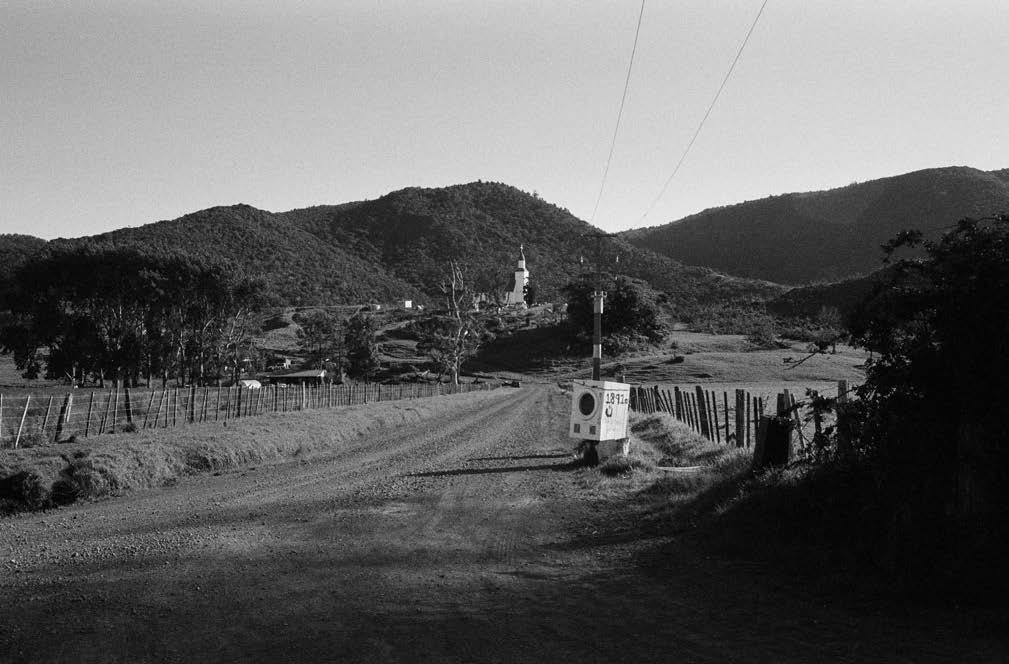

An innovative letterbox on the Pawarenga main road, heading towards St Gabriel’s Church.

Findlay Buchanan is a freelance writer, currently based between the Hokianga and Auckland.

This story appeared in the March 2023 issue of North & South.