BACKSTORY

A leaflet delivered to letterboxes around New Zealand in May this year.

Big lessons from smallpox

Long before Covid-19, people have been sceptical about life-saving vaccines.

By Scott Hamilton

Recently I walked into Glen Eden’s bookshop-cafe for my morning coffee and noticed a pile of magazines near the door. “A man just left them,” the café’s manager explained. “We didn’t want them, but he left them anyway.” The magazine had unflattering images of Bill Gates and Jacinda Ardern, and headlines like “The Covid-19 Vaccine Catastrophe” and “Your Government is Lying to You”. Thousands of copies were being distributed across Auckland by anti-vaccination activists, or anti-vaxxers.

Today the world is full of anti-vaxxers. A survey found that about a third of Americans say they will refuse vaccination against Covid-19. A study by the University of Auckland’s School of Population Health discovered that 20 per cent of Kiwis are also against getting vaccinated.

Anti-vaxxers are often considered a 21st-century phenomenon, a product of the conspiracy theories and paranoid memes that teem on social media. But opposition to vaccination is old. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, attempts to immunise children against smallpox prompted sustained controversy in Europe and in New Zealand.

In the 1700s, smallpox killed about half a million Europeans a year. The disease spread through fluids and through the air. The infected sweated, vomited, and felt boils grow on their skin. When the boils burst they left scabs and an incessant itch. If sufferers lived long enough, the scabs flaked off, leaving pitted scars. In his The History of England Thomas Macauley called smallpox “the most terrible of all the ministers of death”, because of the way it made the faces of loved ones into “objects of horror”.

One day in the 1790s, Edward Jenner, a Gloucester doctor, heard a milkmaid talking happily about how she had caught cowpox, a mild skin disease spread in cow milk. Cowpox, she said, would give her immunity to smallpox. Thanks to this unnamed milkmaid, Jenner made the groundbreaking discovery that cowpox and smallpox were caused by the same virus. He was soon taking pus from a milkmaid’s cowpox-infected arm, injecting it into a small boy, and then injecting the unwitting boy with smallpox. The boy did not sicken with smallpox. Jenner’s unethical experiment upset Britain’s medical establishment, but he got the support of King George III, and by 1820 widespread vaccination had slashed smallpox rates in London. Cowpox-infected lymph was taken directly from calves and injected into humans.

In 1840 Britain’s parliament made smallpox vaccination free, and in 1853 it made the immunisation of babies compulsory. New Zealand’s 1863 Vaccination Act was modelled on British laws. But vaccination was unpopular with many Britons and Pākehā New Zealanders. For some Christians, the notion of taking fluid from a “lower” animal like a calf and giving it to a “higher” creature like a human was blasphemous. Other critics blamed squalor and sinfulness, not a virus, for smallpox. Some parents resented the state’s “interference” in their children’s lives and feared the vaccine would spread other diseases. The doctor Ferdinand Stuart spoke for many when he called vaccination a “mighty and horrible monster”, with the “jaws of the Kraken”, the “horns of a bull”, and a belly filled with “plague, pestilence, and leprosy”.

Leicester became a stronghold of protest against vaccination. Residents refused the practice en masse, and in 1885, 80,000 of them marched behind an effigy of Edward Jenner. In the 1890s the British and New Zealand parliaments moved to soften their vaccination laws. Anti-vaxxer parents were allowed to refuse the procedure for their children. These “conscientious objectors” had to state a reason for their refusal and pay an exemption fee.

He took pus from a milkmaid’s cowpox-infected arm, injecting it into a small boy, and then injected the unwitting boy with smallpox.

In 1904, Auckland’s Registrar of Births explained that, out of 2375 babies born in the city the previous year, only 281 had been vaccinated against smallpox. The parents of 972 babies had paid for exemptions; others had not bothered to register their refusal.

When George Fowlds, a leftwing member of the Liberal Party and loud opponent of vaccination, became Health Minister in 1906, newspapers proclaimed the effective end of vaccination in New Zealand. Smallpox outbreaks had been rare; some settlers believed that geography or climate or morality made New Zealand immune to disease.

Māori seemed keener on than Pākehā on vaccination. An 1849 pamphlet about smallpox in te reo Māori prompted many requests for vaccination. At the beginning of the 20th century, Maui Pomare became Māori Medical Officer and encouraged his people to get immunised. But after Pomare left his job in 1911, efforts to vaccinate Māori faltered.

In 1913, Pākehā attitudes to vaccination changed abruptly. In the autumn of that year a Mormon missionary named Richard Shumway arrived in Auckland from Vancouver. Shumway had a fever and a rash. He thought he was suffering from measles; he had smallpox. Shumway was guest of honour at a hui in Northland attended by representatives of many iwi; his well-wishers took his disease back to their rohe.

New Zealand’s doctors, politicians, and journalists were as slow as Shumway to recognise his condition. In May 1913, Auckland’s District Health Officer acknowledged that some Māori were sick with rashes and fevers, but insisted that they had chickenpox. The boss of Whangarei hospital agreed, adding that Māori were more “susceptible” to chickenpox than other ethnic groups. The mayor of Cambridge said Māori in his district were suffering from “the old native trouble” of hakihaki, or irritable skin.

By July, complacency had turned to panic. As reports emerged of a smallpox outbreak in Australia, and more Māori arrived at hospitals and health clinics, William Massey’s Reform government invoked the punitive Public Health Act. Health officers marched into kainga, raised yellow flags and ordered Māori not to travel without vaccination certificates. Improvised Pākehā militia blocked roads and bridges. At Cambridge, armed men stopped Māori from crossing the river bridge connecting the kainga of Maungatautari with the shops and doctors and vaccinator’s office of the Pākehā town. In Auckland, the Māori of Mangere were forbidden to cross the bridge across the Manukau harbour to Onehunga. Māori without certificates of vaccination were banned from trains and coaches. Pākehā without certificates were free to ride.

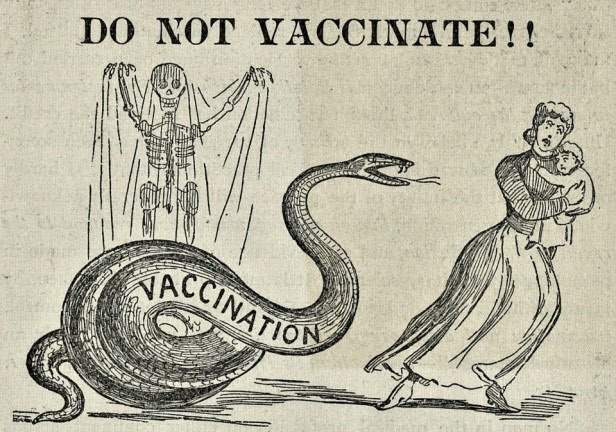

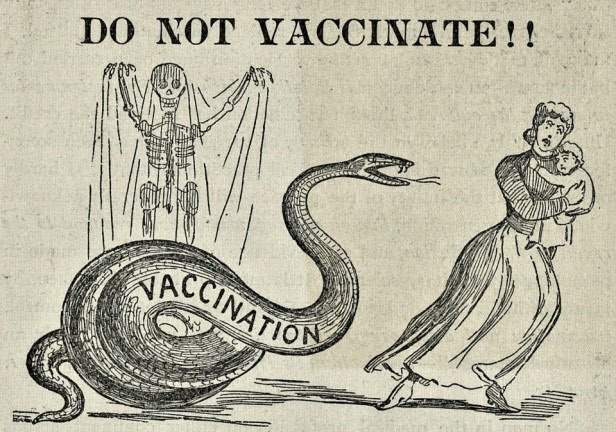

An anti-vaccination cartoon from the late 1800s.

Pākehā justified the isolation of Māori by blaming them for smallpox. The New Zealand Herald said that the disease was “born in the filth” of Māori. Hamilton’s borough council responded to complaints of hunger from nearby kainga by passing a motion calling for “more stringent controls… on Māoris”. “Let them starve,” said councillor John McKinnon during the discussion that preceded the motion. “It is not our funeral.”

As well as isolating Māori, Pākehā rushed to get vaccinated. Supplies of lymph ran low as anti-vaxxers abandoned their convictions. Gisborne, with a population of 12,000, was initially offered only 200 doses by the central government. After complaints from the mayor, another 400 doses reached the town and a crowd besieged the local vaccinator’s office. Some newspapers remarked on this sudden shift: the Evening Post noted that vaccination had become “fashionable”.

We do not know how many people died in the smallpox epidemic, because the disease was concentrated in Māori communities, and in 1913 the government did not bother to record Māori deaths. In 1914, National Health Officer Warren Frengley gave Parliament a report on the outbreak, concluding that the condition of Māori villages was irrelevant to the spread of the epidemic. “Natives living in comfortable homes” were as susceptible as those living in huts and shacks, Frengley said.

The epidemic of 1913 helped change Pākehā attitudes to immunisation. In 1922, a vaccine for diphtheria reached New Zealand; in 1949 a jab for tuberculosis became available; from 1956 a polio shot was given to children. Although some resisted the new vaccines, there was nothing like the mass refusal that made New Zealand vulnerable to smallpox. We should hope that today’s anti-vax movement does not have to learn the same hard lesson.

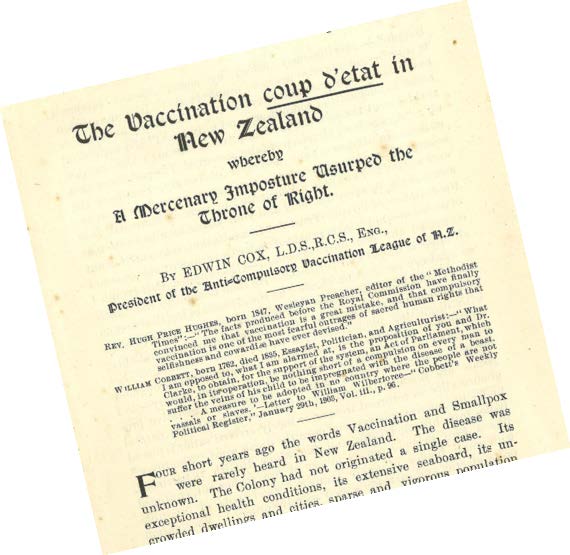

An anti-vaccination pamphlet of 1904 alleged a “Vaccination coup d’etat”. Photo: Courtesy Hocken Collections.

Scott Hamilton has published books about the Pacific slave trade, the Great South Road, and British socialism.

This story appeared in the July 2021 issue of North & South.