Culture Etc.

Above: John Buck overseeing barrel work in the cellar, Te Mata Estate.

The Hunt for Big Red

More than 200 years since we grew our first grape vines, New Zealand is most famous for its sauvignon blancs. But around the country, winemakers are tinkering away, creating silken and symphonic red wines they’re quietly confident could challenge some of the Old World’s best.

By Tobias Buck

Photos by Richard Brimer

For the last four decades, intrepid Kiwi winemakers, viticulturists and vignerons have been stalking the country, soil maps in one hand and tasting glasses in the other. They’ve settled in Northland and the Bay of Islands, in Cromwell and beyond, to the edge of where you can grow grapes on the planet. They’ve followed their noses through frosts and hail, droughts, earthquakes and several lockdowns. Searching among vines and early-morning mists.

They’ve been on the hunt for a fantastic beast, spectacular and rare. It could take a lifetime, but if they catch it they might just change the world’s idea of what can be made here, on a handful of islands in the South Pacific famed for sauvignon blanc. They’re hunting for New Zealand’s “Big Red”.

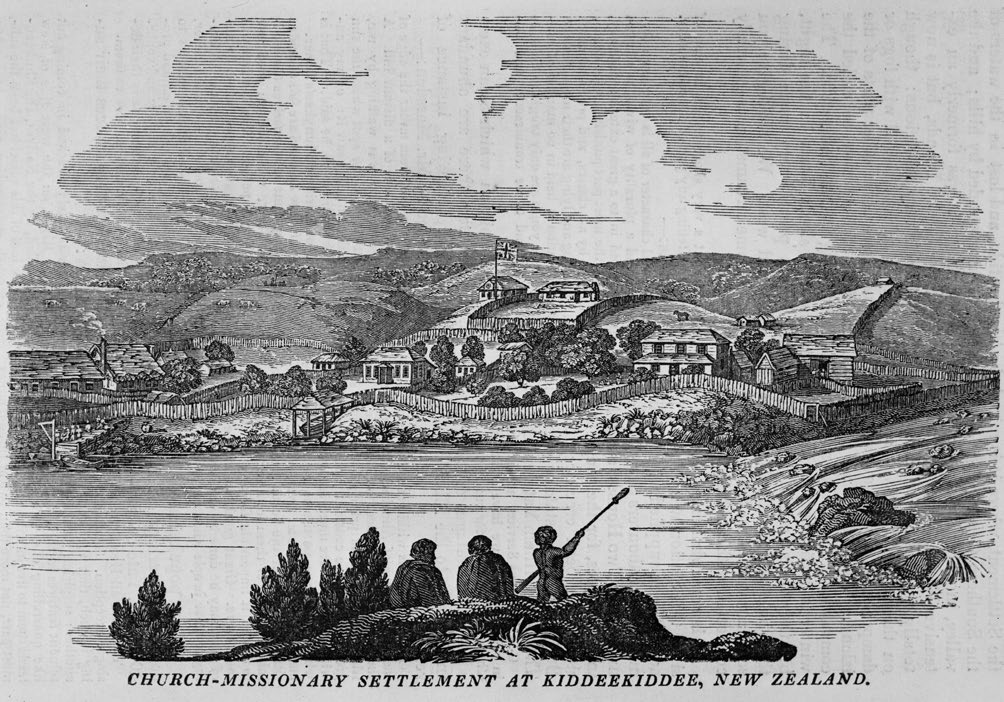

Two hundred years ago, missionary Samuel Marsden planted a hundred different grape vines at a church station in Kerikeri. Records indicate most were destroyed by goats.

On the other side of the globe, in London, a bottle of Pétrus merlot is up for sale. Bids start at £1 million. It’s a French-made red that spent a year cellared on the International Space Station, and its selection for this journey was no accident. On the other side of the globe, in London, a bottle of Pétrus merlot is up for sale. Bids start at £1 million. It’s a French-made red that spent a year cellared on the International Space Station, and its selection for this journey was no accident. 1970s. It’s easily considered one of the world’s “Big Red” title-holders. A seriously fancy red of this kind — of age-worthy and space-worthy quality — is made to develop over decades, giving it a unique allure. Harvested from small pieces of land, the wine’s hard edges and tea-like tannins soften over time. The fruit deepens and mellows. Complexities evolve. International big reds like this don’t just have stratospheric price tags. They’re also trophies. Super-brands. The cultural pearls of France, the United States, Italy, Spain, Argentina. The idea that wines of this calibre could also come from New Zealand soil was once considered a rather precocious conceit.

Church-Missionary settlement at Kiddeekiddee, New Zealand, Engraving, Seelys London, 1830.

Image: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Two hundred years ago, missionary Samuel Marsden planted a hundred different grape vines at a church station in Kerikeri. Records indicate most were destroyed by goats. Fifteen years later at Waitangi James Busby, who also helped draft New Zealand’s Declaration of Independence and the Treaty of Waitangi, recorded the making of our country’s first wines. One was described by a naval explorer as light and white, “very sparkling and delicious”. In the years since, the wine industry has grown exponentially. Wine is now our sixth largest export product, having doubled in the last decade to NZ$2 billion annually. We send our wines to more than 100 countries but even as unprecedented global demand threatens to outstrip supply, only a tiny proportion of our plantings are red. Our signature sauvignon blanc style, a well deserved success story, makes up the vast majority of what we export — 87 per cent. Pinot noir makes up just under 4 per cent of our exports, only slightly more than pinot gris. Fuller-bodied grapes like syrah, cabernet sauvignon and merlot make up less than 2 per cent.

A lot of this is a reflection of what we’ve got to work with. “People forget three quarters of this country’s wineries are producers working with less than 20 hectares,” says Larry McKenna from Escarpment Winery in Martinborough. “These are families. Small businesses. It’s an issue of population and momentum. Every single bottle sold counts, as does there being enough of us for our story to make an impact.”

People associate New Zealand with our singular style of sauvignon blanc, so our lesser-known reds are sold in a crowded, competitive field against extremely well-established regions and styles. As the labour costs for red wine are high, the equipment expensive and the time scales fairly long, red wine remains pricier to produce than whites like sauvignon blanc. Though scarcity can drive demand, the risk of a red not finding its audience is proportionally that much higher, which can discourage some growers.

About 97 per cent of all wine bought in New Zealand is enjoyed that same day.

Craggy Range, Gimblett Gravels Syrah block, home of Le Sol.

“The New Zealand wine industry was born on the back of a jet engine,” says Master of Wine Bob Campbell, only half-joking. Back in the 1970s, wine exports here were negligible, beer was boss, and coffee came out of a can. Licensing laws used to prohibit ordering a glass of wine with food at a restaurant. Air travel opened the world up. By the 1980s, Kiwis were out exploring the world, forming their own ideas, and connecting to the food and wine cultures of Europe and beyond. The Galloping Gourmet cooking show was on TV, hosted by English chef Graham Kerr with a great enthusiasm for good food and wine, cafés were opening, and a new idea of what the country could produce was fermenting alongside a public desire for “better living”. The 1986 Lange government’s slashing of subsidies to farmers and winegrowers meant that developing products of premium quality or prestige could create a potential path to profit.

A government mandate shortly after also meant old vines were pulled and sites replanted in parts of the country as a modern revival of winemaking got underway. A few quality oaked reds from the 1960s and 70s had shown promise — Nobilo’s and Western Vineyards from Auckland, and Tom McDonald’s and McWilliams cabernets from Hawke’s Bay. The first few ambitious, small-scale, premium New Zealand reds began to emerge across the country like home-built supercars rolling out of farm sheds. Among them was The Antipodean blend from Matakana, St Helena Pinot Noir, cabernets from Goldwater, Villa Maria, Vidal’s and Brookfields, Stonyridge’s Larose, wines from Providence and Heron’s Flight, and Te Mata Estate’s Coleraine. (Disclaimer: My father John Buck is founder of the modern Te Mata Estate, and an even bigger enthusiast for New Zealand reds than I am. He’s adamant that when it comes to reds it’s “our bright fruit that can’t be matched”.)

During the 1980s and 90s, winegrowers, winemakers and, increasingly, the public were scanning the hills and sharpening their secateurs. The hunt was on for southern hemisphere examples which matched the world’s greats and spoke with a recognisably Kiwi accent.

At the time, in international wine markets, concentration of flavour was king. Wine writers in the United States and United Kingdom were apt to praise wines for their “great blast of taste”, or equate a wine’s strength or “full bodiedness” with its quality. New Zealand immediately offered an alternative with its temperate, Nirvana-like environment for growing vines, says winegrower Steve Smith of Smith & Sheth, which has multiple vineyard sites across the country. Like Campbell, Smith is a Master of Wine, and has written a dissertation on climatic indices for wine styles. When we chat, the 2021 harvest has just wrapped up and he’s talking quickly before jumping on a morning flight out of Napier. “We’re the only country on the planet with this growing environment, really,” he says. “High amounts of UV, moderate temperatures, young soils, and relatively high humidity. That energy, that perfume and liveliness. You can see it in the fruit you buy on the side of the road. It’s in everything we grow.”

In terms of alcohol or body, even New Zealand’s biggest big reds tend to have an understated quality. Silken and lithe, rather than robust and powerful. Symphonic rather than dominant. It’s a characteristic in tune with modern consumers’ wine tastes and gastronomic trends, and associated with the very best vintages of classic Bordeaux, Burgundy or Rhône. As the world becomes hotter, this delicate quality is increasingly rare in traditional wine regions.

Starting a winery in New Zealand is a possibly fun but undoubtedly quick way to lose a fortune.

Squeezing grapes at Matua Wines in Marlborough.

Though Central Otago is a slight exception, the country’s maritime climate and long, temperate summers tend to give a signature freshness and zip to our white wines, and a vibrancy and drive in our reds. Last year one Master of Wine from the United Kingdom suggested New Zealand could be the greatest region for syrah outside France. Nick Stock, an influential writer and wine critic in Australia and the United States, says “cool-climate syrah is a star of the fuller-bodied New Zealand red wine offering”. With “power, detail and definition, these are the kinds of wines that capture and hold the attention of wine lovers around the world”.

Technical innovations across the industry and winemakers increasingly taking their foot off the cropping and extraction pedals (that is, growing less fruit on the vine to start with and later pressing it less) have contributed to making the particular characteristics of our wines more present than ever. “The vineyards of New Zealand today are chalk and cheese from what they were 30 years ago,” says Smith. “That’s something that outsiders just can’t get their heads around.”

New Zealand has been playing catch up with the Old World since day one, says Rebecca Gibb, a Master of Wine from the UK who’s written a book on the industry here, The Wines of New Zealand. But our comparative lack of history has also been a plus. We’re less beholden to tradition, meaning New Zealand winemakers have been able to innovate and evolve quickly, she says. Gibb is part of a new wave of international experts encouraging others to recognise the improved quality of New Zealand wine. “New Zealand can not only make reds, but refined reds, ones that should have buttoned-up French chateau owners very worried indeed,” she says.

As producers here have gotten to know their sites, free of both the history and the regulations of Old World wine production, they’ve also shrugged off a fair amount of cultural cringe along the way. Smith mentions in passing a red he’s created called Cantera, a blend of cabernet, tempranillo and cabernet franc. It’s his own take on some of the great reds from Spain’s Ribera del Duero, though he says European styles of winemaking aren’t where he looks for inspiration. “Sure, I get a read on what great wines are like. Their depth and complexity. But what we’ve got here is different. And that’s a good thing.”

The list of red wine innovators in New Zealand is a long one. Almost all have a rugged-but-sincere pioneer vibe about them; they’re a mix of gardener, artist, chemist and mechanic. Gordon Russell, winemaker at Esk Valley, is a case in point for both innovation and focus. The Terraces — arguably Hawke’s Bay’s most extraordinary vineyard site — is run by Russell and was planted in 1989 with malbec, merlot and cabernet franc.

“I was always open to more experimentation and willing to push the boundaries, and I’ve always had a soft spot for malbec,” says Russell. Sure it’s unruly, he says, but its burly tannins, spice and “amazing colour” were all part of his process to create a distinctive Hawke’s Bay style. From the limestone soils of this steeply terraced site just north of Napier he makes a single-vineyard wine. “The site was always going to make something unique. Old healthy vines, dry farmed with no weed sprays. An effort to capture the true majesty of the place in the bottle.” The resulting wine isn’t emulating any other in the world, Russell says. Instead it’s a “liquid snapshot” of the vineyard, the hillside, the day and the season.

People coming to live in New Zealand have also brought (and continue to bring) their expertise and attention. Judy Fowler of Puriri Hills vineyard moved to Clevedon from the United States in 1996. She believed an excellent Bordeaux-style wine was doable specifically in the greater Auckland area, with its very mild, cool maritime climate and clay soils, and started Puriri Hills with the intention of making such a wine. “It has worked out pretty well,” she says. The vineyard produces a wine called the Pope, a blend of merlot, cabernet franc, carmenère and malbec, which is now one of the country’s most in-demand reds.

Grant Taylor, Valli wines, in Gibbston Valley vineyard.

An overwhelming majority of all wine bought in New Zealand, about 97 per cent, is enjoyed that same day, meaning only a fraction makes it to our secondary market. But that doesn’t mean the collectors aren’t here. An Auckland auction in March sold aged New Zealand reds at prices well above estimates. One lot of Stonyridge Larose ’08 which had never left the winery went for $470 a bottle — more than double the price expected. With a volatile global economy, well-cellared pinot, syrah and cabernet-blends are something like an investment opportunity. With borders currently closed, money which might have been spent on overseas travel is in some cases being funnelled into tangible assets like art, housing and wine. One bidder at the March auction, also a New Zealand art collector, was quoted saying he had a million dollars’ worth of wine in his cellar.

Jing Song, the managing director of Crown Range Cellar, is one of the people creating sought-after collectable reds. In particular, three bottles of the 2013 Signature Selection Pinot Noir she made in collaboration with Grant Taylor from Valli are attracting a lot of attention in this new social climate. They’re selling for $760 each — almost double their estimates. “I have no problem with what people do, once they’ve purchased it,” Song told the news media website Newsroom. “It’s time, finally, for premium, boutique New Zealand wines to be identified as collectable and as masterpieces.”

Huia Wines in Marlborough, press being loaded before sunrise.

Starting a winery in New Zealand is a possibly fun but undoubtedly quick way to lose a fortune. The capital expense is massive, amplified by our geographical remoteness and each vineyard’s relatively small scale. Almost all wine equipment is imported and each good glass is the result of sunshine hours entirely beyond a winemaker’s control. Every dark cloud is a worry — a year’s work can be lost in five minutes of hail. Wineries often exist on the knife-edge of profitability, from bank loan to bank loan. For those with skin in the game, it’s a gamble keenly felt and ever-present.

Earlier this year, three wineries went into receivership. In 2020, when the first lockdown began, most vineyards still had fruit to pick. There was stillness in the air as the industry held its breath, masks on, waiting for the green light. Eventually, and luckily, harvest was allowed under Covid-safe conditions, but wineries already over-extended were pushed beyond the brink. Ships weren’t able to arrive or leave with stock so wine wasn’t able to reach international markets. An uncertain future meant the gamble of acquiring more debt was too great.

The work and risk involved in winemaking allows little room for pretension. Our farming culture has laid some useful psychological groundwork in this area. The idea that you don’t own the land, but rather that the land owns you, is a hard lesson to learn but a good one. From tūrangawaewae to successive generations farming the same spots (or a combination of both) the concept of kaitiakitanga, or guardianship, has become increasingly embedded in the kind of belonging that has developed here.

Even New Zealand’s biggest big reds tend to have an understated quality. Silken and lithe, rather than robust and powerful. Symphonic rather than dominant.

Rolf Mills, Rippon Vineyard, 1992.

“Drinking wine is a lifestyle choice and an agricultural act,” says Nick Mills of Rippon winery in Wanaka. “For us as winegrowers, it’s no longer about waiting on the benedictions of one critic or another, or even that our wines pass muster in a line-up of global references. It’s about what we do to look after the land, how our own sense of identity reflects the place that has formed us and, ultimately, how this affects purchasing behaviour.”

Another Master of Wine, Taupo-based Emma Jenkins, says we’re right to be proud of what we make here, though she adds that it pays to remember we’re still young. “Some of my favourite New Zealand wines, the ones I think have the most character or are most expressive of their site, are those made by people with long connections to the vineyard itself,” she says. “What excites me about them, and the future, is the sense of humbleness here. The willingness to keep learning and see just how much better, rather than simply ‘bigger’, they can be.”

With three particularly strong recent vintages reaching the world market, our red wine reputation teeters on the edge of critical momentum. Despite having increasingly found our own voice there’s a chance we’ll still end up off the map entirely. But, maybe, hovering on the edge of the world is exactly where we should be. It has proven a fruitful place for evolution, especially if you can keep the goats away.

There’ll always be some kind of search for the title of top red, here like elsewhere. It’s part of our shared simian ancestry, that tendency to remain hung up on recognition and status. But I’m sure that the greatest enjoyment, and meaning, still comes from the most common aspect of wine: that it can be shared with others. Especially when getting together with friends is something the world no longer takes for granted.

Tobias Buck grew up on the Coleraine vineyard and working in the Te Mata winery cellars. He’s presented our wines around the globe, and is also an award-winning writer.

This story appeared in the October 2021 issue of North & South.