BACKSTORY

Bad Dreams

A mysterious sleeping sickness from the early 20th century could give medical historians clues about what to expect when it comes to navigating the troubling but as-yet-uncertain prospect of “long Covid”.

By Scott Hamilton

To defeat an enemy you must understand it, Sun Tzu said in his Art of War. Tens of thousands of the world’s scientists are trying to understand Covid-19, so they can find better ways to treat those suffering the virus and develop vaccines to thwart its spread. Media coverage of these researchers tends to show white-coated men and women gazing into microscopes or petri dishes in laboratories. But some medical scholars occupy very different habitats. They work in library archives, reading old newspapers and manuscripts, or interview the elderly. They are medical historians, who trace the courses of old epidemics, searching for patterns and causes, in the hope of gaining insights into diseases that afflict us today.

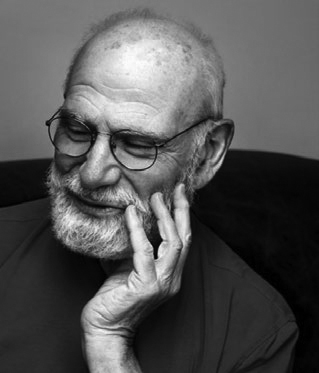

Oliver Sacks’ Awakenings was published in 1973. It is a masterpiece of medical history as well as an affecting memoir. I’ve been rereading the book during lockdown, and finding it worryingly relevant to our situation in 2021. In the late 1960s, the young Dr Sacks got a job at Beth Abraham Hospital — a set of decaying buildings in a decaying part of the Bronx. Beth Abraham housed men and women with chronic, incurable illnesses. They were, Sacks said in a 1973 interview, “lepers of the 20th century”, incarcerated and then forgotten by society.

In dim wards with dripping ceilings and walls of flaking plaster, Sacks discovered scores of sufferers of encephalitis lethargica, infected in an epidemic that lasted from 1915 to the late 1920s. The cause of the disease was and remains mysterious. It attacked the brain, and made victims either lethargic or hyperactive. The disease got the nickname “sleeping sickness”, because sufferers were often unable to move. An Austrian woman succumbed at her wedding, turning into a human statue at the church altar. Another victim fell ill while pregnant, and “slept” right through childbirth. Some sufferers became agitated rather than somnolent: they jerked and jumped, shouted profanities or punched strangers in the face.

Oliver Sacks. Photo: Maria Popova/Wikimedia Commons,

CC BY-SA 3.0.

In 1928 the Auckland Star ran an article warning that encephalitis lethargica was “making criminals”. Afflicted children had “lying and thieving tendencies”, and could even be “homicidal”. The disease was often regarded as a sort of hysteria, and blamed on the moral weakness of the postwar generation.

Half a million people died — of starvation, of sleep deprivation, of opportunistic infections — during the initial stage of sleep sickness. Those who survived longer seemed to recover for months or years, before developing Parkinsonian tremors and rigidity and gradually lapsing into coma-like states. They remained conscious, yet sat or lay silently, for years on end. They were as “insubstantial as ghosts, and as passive as zombies”, wrote Sacks.

Sacks’ book is called Awakenings because he brought some of its victims out of their limbo by giving them the then-new drug L-DOPA. The doctor watched in wonder as eyes opened and stiff bodies climbed from beds and wheelchairs. For too many patients, though, torpor turned in a few months to mania and psychosis. Other patients could not cope with new lives.

Sylvia Schneider was one of the patients Sacks resurrected. When she fell “asleep” she was a young wife and mother; when she “woke” four decades later she was elderly and without any family. Sacks noticed how Schneider used 1920s slang, and referred almost exclusively to people and events of those years. She was a flapper suddenly living in the hippy era. Schneider felt lost and lonely, and eventually stopped taking L-DOPA.

In 1990 Awakenings was made into a movie, with Robert De Niro playing a patient roused by L-DOPA and Robin Williams playing Oliver Sacks. It is strange to watch the movie now, knowing that Williams, who looks so healthy and officious in his doctor’s coat, would himself develop a chronic and incurable disease, Lewy body dementia, that would make his body twitch and jerk, and his mind fog. He died by suicide in 2014.

The sleeping sickness epidemic is important today because of the way it coincided with the influenza pandemic of 1918. Many sufferers of encephalitis lethargica were survivors of the Spanish flu. The two diseases seemed like allies in a war on humanity — in a terrible way, they complemented each other. The Spanish flu was a short, acute disease that often left survivors with damaged immune systems. Sleeping sickness was a chronic condition, that turned recoverees from the flu into, at best, invalids.

Doctor Peter Snow.

Photo: Otago Daily Times.

Emeritus Professor Warren Tate.

Photo: Otago Daily Times.

While most media coverage of Covid-19 focuses on its early, acute phase, many doctors are just as worried about the complex and still mysterious chronic condition that has been dubbed “long Covid”. Sufferers complain that they seemed to recover from Covid, but then gradually developed problems like mental fatigue, confusion and joint pain. Some of them struggle to work; some struggle to leave their homes. A support group for New Zealanders with long Covid already has more than 250 members. There is not yet any agreed diagnostic definition for long Covid. There is not even a consensus on whether the symptoms that the term covers are caused by a single disease.

For the western Otago town of Tapanui, reports of long Covid bring back bad memories. In 1984 Tapanui’s GP, Peter Snow, noticed an odd pattern in visitors to his surgery. Patient after patient told Snow about fatigue and joint pain that went on for months. He eventually diagnosed these patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, which is nowadays known officially as myalgic encephalomyelitis (sometimes referred to as ME). There were 28 sufferers, in a town of a thousand people. Like sleeping sickness before it, chronic fatigue syndrome was a stigmatised disease. A now-notorious cover story in Newsweek magazine called it “yuppie flu”, and claimed it was a “fashionable form of hypochondria” for young affluent Americans. There weren’t many yuppies in Tapanui in 1984, but the outbreak of chronic fatigue syndrome in the town was nonetheless mocked by many New Zealanders. “Tapanui flu” became a synonym for laziness; a popular song had the chorus “I’ve got the Tapanui blues” and the New Zealand Herald ran a cartoon ridiculing the town. Perhaps fear lay under the derision.

Today it is estimated that at least 16,000 New Zealanders suffer from chronic fatigue syndrome. More than a million Americans have the disease. Sufferers have continued to complain of misunderstanding and neglect; they have gathered outside parliaments in hospital beds and wheelchairs to demand better funding for research into their condition.

An Austrian woman succumbed at her wedding, turning into a human statue at the church altar. Another victim fell ill while pregnant, and “slept” right through childbirth.

Chronic fatigue syndrome, like encephalitis lethargica, is now getting a lot of attention from medical researchers. The disease’s symptoms are uncommonly similar to those of long Covid and some scholars, like Walter J Koroshetz, the director of the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, suspect that the two illnesses overlap. Many researchers are now trying to study long Covid and chronic fatigue syndrome together. Brain Research New Zealand has funded a study by Otago University’s Warren Tate into whether long Covid sufferers experience the same biochemical and physiological changes as chronic fatigue syndrome sufferers.

American man Whitney Dafoe suffers from severe chronic fatigue syndrome. For seven years, he lived in a limbo resembling that endured by Oliver Sacks’ patients at Beth Abraham. Too tired to feed himself or sleep, Dafoe lay in a dark and silent room in his parents’ home. His body withered; his skin was too sensitive to touch. Every few months, he was able to type a terse message onto a tablet. “Chronic fatigue sounds too banal”, said one message. “I call it total body shutdown.” Dafoe’s father is Dr Ron Davis, a renowned geneticist who works at Stanford University. When Whitney got sick, Davis assembled a team to study chronic fatigue syndrome. When he is not caring for his son, he studies blood taken from sufferers of the disease. “I’m racing the clock,” Davis told one interviewer. “I’m trying to save my son.”

Last year Dafoe’s condition improved slightly. He was able to sit up in bed, smile, and clench a fist in defiance at his disease. He has since made a series of poetic social media posts and published a 23-page essay about the epic battle he has fought in his bed. Dafoe believes that, with the epidemic of long Covid, the general public and medical establishments can no longer ignore the sort of symptoms he has suffered for so long. In a recent Facebook post he predicted that the “wall of ignorance” about his illness would soon come “crashing down”, and that sufferers like him will “rise from the dark like illuminated ghosts”. To understand and defeat Covid, we may have to do the same to some other, older diseases.

Scott Hamilton is an historian and regular contributor to North & South. His last column explored the history of the Cook Islands.