Lost in Transit

Hundreds of loved ones have been divided by Covid border policies for over a year. Can’t the country of “be kind” do better?

By Branko Marcetic

Just about every married couple can tell you a story about the last-minute twist that nearly derailed their wedding: unexpected food poisoning, maybe, or the sudden flare-up of a family feud. For Bianca and her husband Carl, it was the deadly pandemic that turned the location of their big day into an 800-square-kilometre biohazard. Getting married in the middle of it turned out to be the easy part.

Bianca is a Kiwi; Carl is an American. (The couple requested pseudonyms to protect their privacy.) They met in the United States in late 2019 while Bianca was on a work trip and began a long-distance romance that saw her shuttling back and forth between Auckland and New York. After a few months, they decided to marry, setting the date for March 2020. It would be a small wedding, with Carl’ best friend and his partner attending in person, and Bianca’s elderly parents and loved ones around New Zealand tuning in via FaceTime.

By the time Bianca left for New York, the World Health Organization had declared the coronavirus a pandemic. Almost as soon as she landed, her social media was aflame with news of rising cases and closures in the city. As she scrambled to salvage her wedding, her travel agent warned her of a much bigger problem: flights back to New Zealand were disappearing. With no US immigration status beyond a three-month travel authorisation and family obligations at home, Bianca had to go back. They married on her fourth morning in New York, with disposable gloves on their celebrant’s hands and only a photographer in attendance. That afternoon, Bianca was on a flight home. Carl, who has no New Zealand immigration status, had to stay behind.

“We really didn’t even get to have a meal together,” she recalls.

The newlyweds were anxious to be reunited. In September, with the US logging tens of thousands of infections per day, Bianca flew to “the worst place to visit on earth” for their honeymoon. She intended to stay four weeks. Shortly after she booked the trip, the New Zealand government announced that it would start charging travellers for managed isolation and quarantine (MIQ), adding $3,100 to an already pricey trip and halving her time with Carl. Flying back and forth was no longer an option.

So the two turned to getting Carl a critical purpose visitor visa (CPVV) for New Zealand. On paper, they had a good case. They were married, she had lived in his home on several visits, they had proof of shared financial transactions, and he was the executor of her will. By way of proof, they dumped 800 pages of evidence on Immigration New Zealand’s (INZ) desk, says Bianca, including 32,000 texts, 732 audio messages, thousands of photos, videos, and call records, as well as letters from family, friends and her employer.

In November, they were declined. INZ’s response said that staying in each other’s homes during their regular visits wasn’t evidence they were “living together in a genuine and stable relationship” — although the fact they were from different countries made it impossible to live in one shared home.

By now, Bianca and Carl have been apart for 15 months. Most of their marriage has been conducted over the Internet. They have spent more than $16,000 on their efforts to be together, estimates Bianca, $7,000 of it in unpaid debt. Their last option was for Bianca to take another expensive trip back to the United States to prove their relationship is genuine and apply again from there. But even if they were successful and Carl was able to travel here, the couple cannot afford the increased MIQ fees for visa-holders that were announced in March. “It has been extremely stressful and draining,” says Bianca.

They married on her fourth morning in New York, with disposable gloves on their celebrant’s hands and only a photographer in attendance.

The New Zealand government has won deserved acclaim around the world for its efficient, humane response to the pandemic. But its border policy has been a very different story. More than a year on, the system remains mired in confusion and inequity.

Those affected include citizens like Bianca and people with valid New Zealand visas who lived and worked here for years before the pandemic. Often, it was a cruel twist of fate that divided them from their loved ones — family members whose trips were booked just too late, or who travelled overseas at just the wrong time.

While no comprehensive official count exists, the most recent available government numbers showed 1,092 partners and children of work visa-holders who had visas prior to the border closure were unable to travel. According to immigration advisor Katy Armstrong, “families that need reuniting run into a few thousand”. “The border is anything but fair”, she says. (An INZ spokesperson acknowledged the difficult situation for migrants and families but said the agency “has no ability to apply discretion when considering requests for border exceptions”.)

Most members of separated families support the unprecedented steps the government took early in the pandemic, including closing the border. “Just about every person I’ve been in touch with understands New Zealand wants to keep the population here safe,” says Anu Kaloti, president of the Migrant Workers Association. “I’m actually amazed by how tolerant these people are.” But after more than a year, the stresses are becoming unbearable.

“Marriages have started to break down, kids have started to develop mental health issues and behavioural issues, and at the more serious end, you’ve got self-harm,” says Erica Stanford, the National Party’s immigration spokesperson. “It’s at crisis point.”

What is hardest, says Bianca, is “the randomness” — the seeming lack of any logic behind who gets in and who gets denied. A particular sore spot is the so-called “high-value” workers allowed entry while families languish: film crews, sportspeople, entertainers, and sometimes even their nannies. This March, with thousands of families still separated, 133 spaces were found in short order for foreign workers who were part of a stage production of Lion King and a Queen tribute act.

Danie and Claire Breadenkamp were sick of the crime and lack of opportunity in South Africa. Back in 2017, the couple, who are now 37 and 38, started planning to move to New Zealand with their two young children. Danie was a mechanic — a position on the skills-shortage list — so they applied under his name.

Two years later, after Danie secured a job from an automotive repair shop in the North Island, his visa arrived — just as what was possibly the world’s earliest known case of Covid-19 emerged in China.

The Breadenkamps had given up everything for the chance to raise their kids in a place where they could cycle to school safely. After closing his business, Danie arrived in New Zealand on 1 January, 2020 and began saving for his family’s arrival. Back in South Africa, Claire sold the car, gave up the rental they’d called home for nine years, and moved in with her parents. The kids shared one bedroom; Claire slept in the lounge. The plan was to leave during the South African school break six months later to minimise the disruption for their eight-year- old son, who experienced behavioural challenges when his routine shifted.

When the border closure was announced, the Breadenkamps expected it to last only a few months. Claire scrambled to complete her police clearance and medical exam before South Africa went into hard lockdown, and finalised the family’s visa applications in May. Danie assumed that as soon as New Zealand came out of lockdown, INZ would start processing their case.

A year on, Claire and the kids are still in South Africa, where the virus is in its third wave. When I spoke to the family in March, their four-year-old daughter was wetting the bed and suffering from night terrors. Claire overheard her saying that her father was dead. Their son was prone to fits of anger and wouldn’t speak on the phone to his father for more than a few minutes. A therapist’s assessment viewed by North & South describes him as suffering from anxiety and loss of control.

Abhishek Mahajan, 29, is in a similar situation. He has been living in New Zealand since 2016 and works as telecommunications technician — an officially designated essential service. He and his wife, Reetika, who is in India, were friends for 10 years before expressing their feelings for each other. After they married in India in October 2019, the two started putting together documents for her partnership visa so she could join Abhishek in New Zealand. In February 2020, they found out she was pregnant.

The timing of the pregnancy made it difficult for Reetika to travel alone. So they decided to wait until the baby was due in June, when Abhishek would travel back to India and apply for visas for both of them. The sudden border closure in March derailed that plan. And with policies around the world changing rapidly, leaving the country was a tremendous risk.

Abhishek had spent four and a half years working to build a life here for his family. He wasn’t willing to abandon that right away. When he applied for a border exemption in February for his wife and child, he was told that his situation didn’t fall under “exceptional humanitarian circumstances”. On his lawyer’s advice, he is waiting for the right time to re-apply. He has still not met his baby, now an 11 month old who reaches out to touch the phone screen when he calls her name. “It’s very hard for me to control my emotions,” he says.

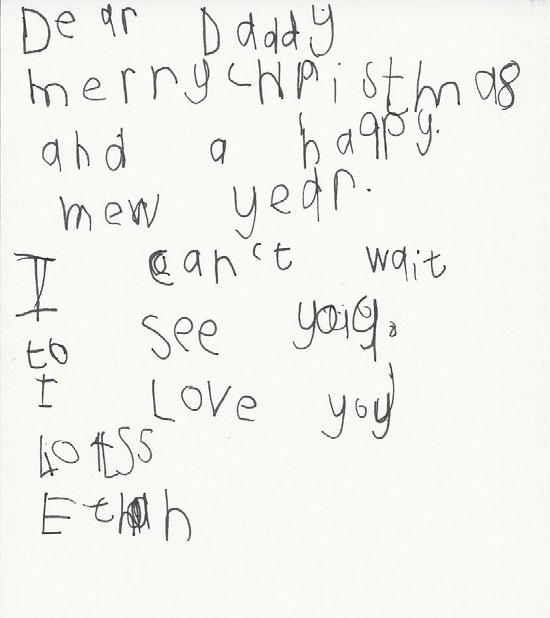

A Christmas message from Danie’s son. Photo: Supplied.

Claire with her children at the beach in South Africa. Photo: Supplied.

In many ways, Covid intensified an immigration crackdown that had already started. Labour campaigned on a promise to cut net migration by 20–30,000 a year. It never fulfilled this in government — overall immigration remained fairly steady. But this was partly thanks to a large number of people coming in on temporary visas — 60 per cent of all migrants in 2019. Meanwhile, the government cut residence approvals to their lowest level this millennium, curbed foreign students’ post-study work rights, and took a harder line on partnership visas. Between 2015 and 2020, the number of temporary work visas grew 76 per cent, to 200,000. The number of residence approvals last year has barely budged in two decades — 47,600 in 2019–2020, compared to 44,598 in 2000!2001. The government is happy to let more temporary workers in to meet employer demand, but has been narrowing their chances to stay.

Jessy and Felix are migrant workers from India who came to New Zealand hoping to build a better life for their young daughter. (They asked North & South not to use their last names.) Jessy, 29, was in India for her child’s first two birthdays. She moved to New Zealand to study at the end of 2018, with Felix following, initially on a visitor visa. The limited hours she could work on her student visa made it financially impossible to bring their daughter, who stayed in India with Jessy’s parents. Jessy and Felix didn’t take the sacrifice lightly, but hoped to bring her over within a few years once Jessy could work full-time. In the meantime, Jessy missed her daughter’s first steps, her first words, her first day at school.

Finally, last year, Jessy finished her studies. She and Felix left the family they’d been living with, moved into a two-bedroom rental and applied for a visa for their little one. Nine days after the visa was granted, the New Zealand border closed.

Jessy tried and failed multiple times to secure a border exemption for her daughter. INZ told her that her daughter meets two of the three categories—she’s a visa holder and a dependent. But because she doesn’t ordinarily live in New Zealand, she doesn’t qualify. The fact that Jessy and Felix both do essential work here — she in disability services, he as a healthcare assistant in dementia care — makes no difference.

This April, the government announced that those who held visas before the border closed, like Jessy’s daughter, could finally enter. But the recent Covid surge in India rendered this decision moot for Jessy and Felix. New restrictions on travel from India meant Jessy would have to go pick her pre-schooler up there, travel to a third country, then back home. There was no way they could afford three back-to-back quarantines. In June, INZ told her she would have to wait for the restrictions on India to lift before applying again.

Jessy and Felix’s daughter on her birthday in India. Photo: Supplied.

On video calls with Jessy, her daughter sees an airplane and announces that her mum is coming; she holds up a mango and says they’ll eat them together in New Zealand. One day, as Jessy was preparing to sit an exam, she got a call from her father: her girl was in the hospital, after falling and cutting her head. “I was really blank, I don’t know what to do,” she says. “My friend was also with me. She said, ‘Don’t cry, don’t cry.’ But I can’t control myself.”

There are two major obstacles for migrants like Abhishek, Jessy and Felix. One, says immigration lawyer Alastair McClymont, is that people from the Global South seem to face a tougher standard in the application process from INZ. For people applying from Europe or the United States, he says, “you don’t worry about the same level of documentation.”

The other is the built-in legal handicap of coming from a non-visa waiver nation. New Zealand has agreements with a few dozen countries — mostly in North America, Europe and wealthy nations in the Middle East and Southeast Asia — that allow their nationals to travel here without a visa, and vice versa.

When this two-tier system was extended to border exemptions, it created dire disparities that continue to this day. After the border closed, government policy was that partners of Kiwis could not enter the country unless the couple travelled together. So Kiwis shelled out thousands of dollars, took weeks off work, or even quit their jobs to meet their partners overseas, apply for border exemptions, and pray they’d make it through the multi-round approval process before their time or money ran out. (All before booking a plane ticket home and doing their two weeks in managed isolation.)

In September, after months of criticism, the government finally announced that such “fetch missions” would no longer be necessary — for partners from visa-waiver countries. Partners from non-waiver countries would still need to be accompanied by their New Zealand partner, with all the distress and expense that entailed. It’s not only migrants who are affected by this rule. There is, after all, no border that decides who a Kiwi can fall in love with.

Until the pandemic, New Zealanders led increasingly international lives. Among OECD countries, we have the second largest proportion of our population living overseas (14.1 per cent). This inevitably means more cross-border families and relationships. Every year, the government approves in the vicinity of 10,000 partnership residency visas. A 2020 survey of expat Kiwis by the organisation Kea found nearly a third of those planning to return were bringing a foreign spouse with them.

Emma was one of those expats. After swapping her North Island small-town roots for big city Australia, two years ago she met Dwele on holiday in South Africa. (Both requested pseudoynms.) Upon returning home, he to Nigeria and she to Melbourne, they started a long-distance relationship. Within a couple of years, they had bought a house in Australia, had a joint business registered in Nigeria, and a plan: she’d live with him for a year in Nigeria before they made New Zealand their long-term home. And then came Covid.

After the pandemic made visiting each other impossible, Emma fell into a depression and moved home to New Zealand to be near whānau. She soon found a job in her niche area of IT. But there was no way for Dwele to join her. So Emma made the excruciating decision to go and get him.

No one in her family wanted her to do it. The trip would be hugely expensive, and Emma has respiratory health issues that made her vulnerable to Covid. Even her partner questioned if it was a good idea. “I was a crying mess the day before, because I did not want to get on that plane,” Emma says.

The process “ruined us financially,” says Emma. Had her partner been British or American, the entire ordeal could have been avoided.

The first leg of the trip went smoothly. With a bundle of N95 masks, cleaning material, and a business-class ticket for extra isolation, Emma spent the mostly empty flight masked and sanitising everything. It was a different story in Qatar, where a busy airport forced her to spend the 19-hour stopover holed up in a transit hotel room, then try to find some safe space in a teeming gate lounge. From there, Emma spent seven-and-a-half hours on a packed flight to Lagos, arriving to what she describes as “craziness” at Nigerian customs.

“There was no social distancing at all,” she recalls. “Lining up to get to the customs desk, I’d say there were well over 100 people, all on top of each other. I was freaking out”.

When North & South contacted Emma this year, she was still in Nigeria, waiting for her partner’s visa to be approved. Her Nigerian visa was set to expire in exactly one month and there were no spaces in MIQ. She estimated they had spent more than NZ$30,000 during her time in Nigeria on immigration expenses and the logistics of travel, with a return flight and MIQ still to come.

Even after obtaining the critical purpose visa, the nightmare wasn’t over. The only flight option required an Australian transit visa for Dwele — another agonising process that took more than two weeks as the days on Emma’s Nigerian visa ticked down to single digits. If they couldn’t get transit visas in time, Emma would have to pay US$1,000 to renew her Nigerian visa and risk losing her job at home — all on top of another US$3,400 each for flights and an MIQ price hike of around NZ$2,000 per person. The process “ruined us financially,” she says, leaving her on the brink of a breakdown. Had her partner been British or American, she notes, the entire ordeal could have been avoided.

A few days after we talked, the transit visas went through. By June, Emma and Dwele were settled in the town she grew up in, ready to run another bureaucratic gauntlet to secure him a work visa. Emma feels mentally drained and traumatised. And this is a happy ending.

The justification for New Zealand’s strict border policy is that it keeps the virus out. Yet INZ’s stringent requirements force people like Emma to make dangerous trips overseas, spending a significant amount of time in Covid hotspots. This risks both the health of individual Kiwis and bringing the virus across the border.

Take Alistair, 50, a Kiwi military veteran stuck in the Philippines with his wife Briely, 43. (They asked us not to use their last names.) Fifteen years of service, including stints in war zones like Sierra Leone and former Yugoslavia, left Alistair with debilitating mental health issues, which flared up when the Philippines went under lockdown last year. Without access to medication or counselling, Alistair’s health deteriorated, forcing him to make what he calls the “fucking horrendous” decision to take a flight home in April 2020 that was four times more expensive than normal. After four months in rehab in New Zealand, Alistair had stabilised and the couple planned to bring Briely to join him. But since the Philippines isn’t a visa-waiver country, this was the start of a whole new ordeal. “This has taken every single cent of our life savings,” says Alistair, estimating that the couple had spent around NZ$23,000.

Alistair had to return to the Philippines so he could fly back with Briely. The Philippines’ travel restrictions meant he technically couldn’t enter the country without a return ticket. But without knowing when Briely would be approved for a visa or when they could get spots in MIQ after that, he didn’t even have a return date, let alone a ticket. The airline let him board anyway — wrongly, it turned out, causing him to be detained by Philippine border control.

Once he got out, Alistair began the process of obtaining temporary residency in the Philippines so that that couple could open a joint bank account, which lawyers advised them is one of INZ’s chief requirements for proving a relationship is “genuine and stable”. Briely had sold her condo and quit her nursing job in preparation to leave. After spending five months and two lockdowns living with her family, the two were able to lodge a CCPV application in May. Despite providing evidence of the urgency of his medical situation, Alistair says INZ informed him the couple would likely be approved by July — two weeks after his medication is due to run out.

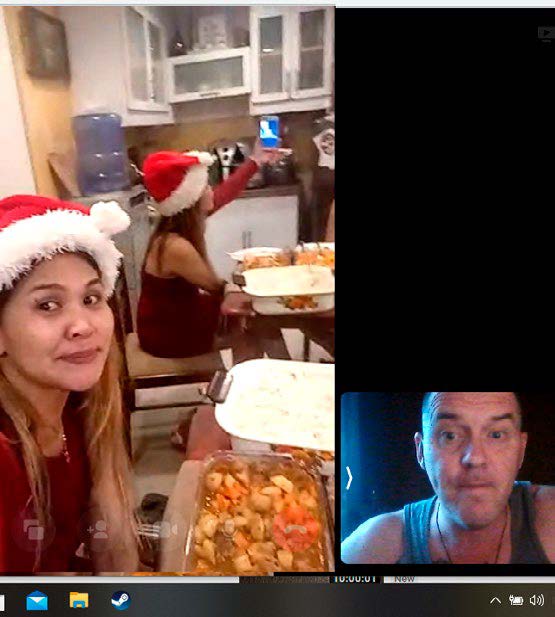

Alistair and Briely share Christmas dinner, approximately 8,000 kilometres apart. Photo: Supplied.

By far the most consistent source of distress cited by separated family members is a feeling of limbo. With no roadmap from the New Zealand government, they have nothing to look forward to and no way to plan.

“Even if they can just give us a date, or just blatantly tell us, ‘Sorry, we’re not going to do it this year,’ then at least I can make the decision of whether I’m going to stick this year out on my own or give up and go back,” says Danie Breadenkamp.

The chaos ripples beyond those directly affected. A significant number of Kiwis and migrants split from their loved ones are essential workers or in positions on the skills-shortage list, including in health care. Immigration adviser Katy Armstrong has around 80 letters of support from businesses around the country, across many industries, calling for their employees to be reunited with their families. “If you’ve got a depressed work force, it’s going to pass on into the community. I wouldn’t want to be nursed by somebody who hasn’t seen their baby,” she says.

“If we can be number one internationally in terms of curbing this pandemic, we should be able to do remarkably well in dealing with migrant issues as well,” says Anu Kaloti.

There’s no shortage of ideas for how to make the system more humane. One is to rescind the “fetch mission” requirement for family in non-visa waiver countries. Another would involve simply prioritising the order that cases are processed — by length and severity of separation, or whether the applicants are existing visa holders, or the numerous factors officials regularly weigh up when evaluating any immigration case.

The government could also set aside a monthly percentage of all MIQ spaces for separated family members, ensuring there is a steady number coming in, which would give people at least some way to estimate when they can see their loved ones again. It might consider reinstating and extending visas for anyone who held one but was trapped offshore by the border closure.

There’s no doubt the pandemic created enormous and complex challenges for border policy that had to be figured out on the fly. But the same was true when it came to tackling the virus itself. “If we can be number one internationally in terms of curbing this pandemic, we should be able to do remarkably well in dealing with migrant issues as well,” says Kaloti.

In April, the government extended border exemptions for partners and dependent children of health-care workers, for people making twice the median New Zealand salary of $53,040, and those who held visas before the border closed. Even Faafoi acknowledged the rules still leave out “thousands”, including all of the Kiwis and migrants profiled in this story.

“They’re not having new applications coming for residency or temporary visas for a year now, so you must have hundreds of immigration officers available,” says former immigration minister Tuariki Delamere, now an immigration adviser and spokesperson on the issue for The Opportunities Party. “Why aren’t we able to reduce the backlog?”

In late November, about a hundred people from around the North Island packed into a Hamilton school hall for a meeting with Labour MP Jaimie Strange, recounting devastating stories of their ordeals. According to those present, the event left the room of participants in tears, with Strange promising to take complaints directly to Faafoi.

Nearly all of those interviewed recount contacting their MPs, Faafoi, and even the Prime Minister’s office, over the last 15 months. If they got a reply, it’s usually been a boilerplate apology that nothing can be done. At the end of February, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern told Newshub Nation that limited capacity in MIQ would make any short-term solution “tough”.

Many of those advocating for split families suspect the issue is part of a shift in policy. Faafoi has warned that numbers won’t return to pre-pandemic levels, urging Kiwis to fill the jobs that rely on migrant labour. In a February Facebook post, Ethnic Communities Minister Priyanca Radhakrishnan cited the impact of thousands of returning Kiwis on the labour market as part of the reason why the government couldn’t do more for those stranded off-shore.

“INZ rejects the notion that border restrictions are part of a strategy to cut migrant numbers,” the spokesperson said, adding that any policy changes must balance economic, social and humanitarian objectives with the need to protect New Zealand.

Since 2017, New Zealand has projected itself as an island of kindness in an increasingly intolerant world. The long-term separation of partners and families, and the government’s arbitrary, unhurried response sits glaringly at odds with this image.

“We are thinking maybe, maybe this government will do something for us,” says Abhishek Mahajan. “Because this is our dream country. When we are back in our home country, we think about this country.”

“Split families — everyone now has been separated for nearly a year,” says Danie Breadenkamp. “Have we not shown that we are committed to making this work, that we want this to be our home?”

Branko Marcetic is a staff writer at Jacobin magazine.

This story appeared in the July 2021 issue of North & South.