Culture Etc.

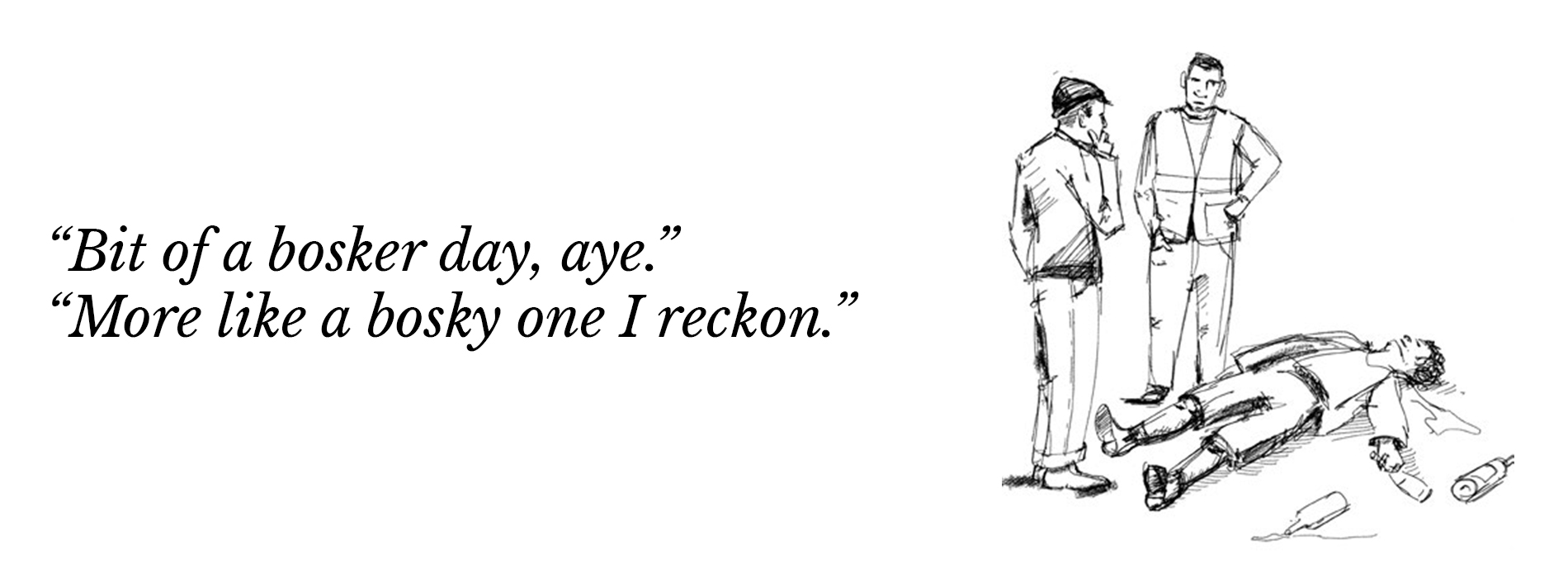

Above: Illustration by Imogen Greenfield.

Bosker Days

What do we lose when a piece of iconic kiwi slang is uttered for the very last time?

By John Summers

What happened to all the jokers? If your first thought is Batman, then my point is made. I was thinking of those jokers, of that joker over there. The word that is used to mean men in a way that is slightly jocular, gently contemptuous. It’s a long time since this has happened in my presence. Possibly it is endangered, used only by a decreasing number of New Zealanders, or maybe it’s just me that has moved out of earshot and the word still thrives. Either way, the question got me thinking about another piece of slang once used in this country, “bosker”, which I have only ever seen in print, specifically, within the Depression-era stories of Frank Sargeson. “So we all stuck our feet into cow-pats, and after walking over the frost it was bosker and warm sure enough,” says the narrator of one. It is a cheery presence in his writing, used to mean something great, terrific or good, and is one of those words that happily looks and sounds like its meaning. It is also almost certainly extinct.

The godfather of 20th-century English slang, that is, the first to document it with all the rigour and scholarship it deserves, was born near Gisborne. As a boy, Eric Honeywood Partridge heard his father argue with a neighbour over what he called a “humble bee”. Later, he’d check a dictionary and learn that his father was wrong, the insect was a bumble bee, but later again, in another book, he would find his old man redeemed. There existed that term, ‘humble bee’, an old English name for what we now call a bumble bee that had dropped from use. This Partridge credited as an early insight into the richness of language, and another would come soon after when his family moved to Australia and he needed to learn the whole new lingo of Aussie slang.

In later life he served in World War I, fought in Gallipoli and on the Western Front before “stopping one” as he would write (that is, getting shot) in the Battle of Pozières. Almost seven thousand Australians would either be killed outright or die from the wounds they suffered at Pozieres. One historian would describe it as the worst place on Earth. But to read Partridge’s memoirs is to discover that what was most memorable was the mingling of lexicons. The trenches held clerks and petty criminals, wharfies and members of the gentry. The slang of the British Empire was there for the hearing, and Partridge was listening. He would go on to publish Songs and Slang of the British Soldier 1914–1918, the first of his studies and a precursor to his magisterial Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. All up he would write more than 40 books about the English language. The word he would choose to describe himself: addict.

While paging through the 1949 edition of Partridge’s dictionary one morning in the National Library Reading Room, I learned, among the hush and the scrape of turned pages, that bosker is a variant of the better known bonzer, an Aussieism that can also mean “anything excellent, delightful”. But Partridge’s focus was broad, it encompassed all English-speaking nations. And so, on that same morning, I also looked to a slim hardback with pages rounded by years of use: Sidney Baker’s New Zealand Slang, published in 1941 on the promise of being the first such dictionary in this country. There bosker would appear only once, without description, in a list of words in “constant use by our youngsters”.

“Let me introduce myself, I am the Humble Bee.”

Illustration: Imogen Greenfield

In a journal article written around the same time, “English as it is Spoken in New Zealand”, I would find bosker again, but also two words that caused me to pause: “pretty punk”. For a sudden second my grandparents came alive. The only time I had encountered this phrase was in their company more than a decade ago. The author of this article described it as having a meaning similar to lousy and that was the way they used it too. “A pretty punk sort of thing,” they said to show disapproval. I never asked what they meant. It was clear from the context and I figured this was some old meaning of “punk”, but until reading this article I didn’t realise that it was a complete phrase with “pretty” a part of it. Nor did I realise I was in the presence of two native speakers of a language no longer spoken. Bosker, an academic would later tell me, was a word most commonly used by casual labourers on docks — a working arrangement known as “seagulling”. The latter was another word I had heard from my grandparents. My grandfather had done this job in the years before the war, the very era Sargeson was describing. It is likely that my grandfather heard the word bosker, maybe he had used it himself but if so, I never heard it from him, and it was now much too late to ask.

I’ve since read various theories on how bosker came about. It is generally considered to have come here from Australia. A 1918 story in the Thames Star tells a colourful tale of it deriving from the French expression “plus beau que ca”. Another theory is that it derives from an old English term, bosky, for being drunk. All very interesting maybe, but for me what made it fascinating, what kept me paging through all these books, was its absence. It existed only in writing, a remnant of a way of life, a way of talking. I imagined the work of those wharfies. The tough business of heaving things on and off ships, tempered by the luck of finding a job in those hard times, the hope this might have brought. Maybe things were starting to look up! A camaraderie surely came with all this, something best expressed through a language shared. “Bosker”, you might say, the last crate loaded and time now to see the boss about pay. They’d all know exactly what you meant.

Theories about “bosker’s” origin were all very interesting, but for me what made it fascinating was its absence. It existed only in writing, a remnant of a way of life, a way of talking.

It is estimated that a language dies every fortnight, and with each goes whole ways of knowing, communicating, of enacting culture. This is tragic, dramatic, and I wouldn’t dare claim the same for the disappearance of a word like bosker. But even so, in some small way, we surely lose something when old words bite the dust. Sure, we can read the dictionaries, as I have, to learn that bosker meant excellent. But was it a word you might use in polite company? Was it crude or tough or childish? In putting it in the mouths of his characters, Sargeson offers the strongest clue.

The accepted wisdom is that Sargeson’s stories were among the first to truly mimic the speech of Pakeha New Zealand. But that way of speaking has changed and the voices in his stories can now only be read as quaint. His writing no longer offers the shock of seeing the way we speak in print — if in fact it ever did. Maybe people saw those words in his stories and thought they were quaint even then, that Frank hadn’t got it quite right, or had laid it on too thick. We can find out maybe, but we have lost our opportunity to know. If we place this world as of the pre-war years, then its inhabitants are all but gone. It exists in his books, in those dictionaries as ancient history. The hush that I had encountered in that reading room and took to be the sound of scholarship, was also the quiet of a tomb.

And yet, I have no urge to reinstate these old words. Firstly, our duties lie elsewhere, in the first language of this country, and secondly, I cringe at the thought. In my reading, I came across a number of small books that collect New Zealand slang for laughs. ‘‘In any case, before we get too carried away and go arse over tit, grab your cuz and have a gawk at the grouse words of wisdom that follow” reads the introduction to Justin Brown’s Kiwi Speak, thrusting these words at us like a novelty t-shirt. I’m being snobbish I know, but I can’t help but think there’s something insecure in pretending we still pepper our conversation that way. These words have come and they will go, replaced by whole new ways of speaking. Ours is a living culture, a compost. We can remember and we can mourn. But beyond that we are powerless to live anywhere but the present. At some point, somewhere, someone was asked how the day was going and bosker was the answer. It had been a bosker day, and it was the very last.

John Summers is a Wellington based writer. His essay collection, The Commercial Hotel, was published by Victoria University Press earlier this year.

This story appeared in the April 2021 issue of North & South.