Click and Collect for Drugs

How the internet is convincing Kiwis that buying drugs is as safe and convenient as online shopping.

By Pete McKenzie

Illustration by Ruth Gwily

The sun was still up when Scott* parked his Subaru Legacy on Onslow Road in the leafy Wellington suburb of Khandallah. Sitting outside a boxy set of flats overlooking the harbour, the 20-year-old student messaged the man he was meant to meet. He was late to a friend’s 21st; he planned his apology while he waited.

* Names have been changed

The man slipped out of the flats and into Scott’s car. They hadn’t spoken in person before. After some stilted banter, he showed Scott a large Ziploc bag packed with loose crystals of MDMA. The bag’s size didn’t surprise Scott: he had come prepared for a big deal. The dealer asked to see Scott’s cash, prompting him to pull out a wad of notes totalling $4,500 — a fair price at the time, in 2020. That’s when things started to go wrong.

“Oh, is this all of it?” the dealer said, according to Scott. “And I was like, ‘Yeah bro, I’ve counted it twice. I’ve sent you a photo of the money already, it’s all good.’ And he said, ‘Oh cool, I’m taking it then.’”

The dealer punched Scott in the head multiple times, got out of the car and sprinted down the road with the money and the drugs to a beat-up Honda Civic. His head pounding, Scott ran after him. A week before he’d been scammed on the same street by a different dealer. He’d paid $3,000 for what he thought was MDMA, but when he sold it on to his web of friends and acquaintances, it became clear that he had bought rock salt. If he didn’t get his customers more product he’d be in serious trouble.

Scott stopped a few steps short of the dealer’s car. Through the window, he could see “four other massive, tatted-up dudes. And they’re just staring at me. And I thought: this isn’t worth getting stabbed over.” Scott went back to his car and drove away.

In less than a week Scott had lost $7,500 and he was terrified. He skipped the 21st and returned to his flat. When his flatmates saw his bruises and busted lip, they guided him to the couch. And after checking he was okay, they made one thing clear: Scott had to delete Discord from his phone.

Founded in 2015, Discord began as an online platform for gamers to communicate with friends. Users created “servers”, or communities, where they could talk by voice chat or set up text-based channels to banter. At its core, Discord is a souped-up version of old internet chatrooms, with a glossy interface and a guarantee of anonymity. This was a crucial selling point for the hard-core gaming community: their online friends were real friends, but they were sceptical of sharing personal details with people they might never have physically met.

Now, the platform is used regularly by more than 150 million accounts around the world. (By contrast, approximately 200 million accounts use Twitter every day.) Its servers are hubs where people gather to chat about every kind of interest you can imagine, from sports to crypto trading to anime to Minecraft. One tech writer observed that Discord had “(somewhat accidentally) invented the future of the internet”. In 2021, its owners rejected a US$12 billion takeover offer from Microsoft.

But its combination of anonymity and easy connection wasn’t only attractive to gamers. Early in Discord’s life, it gained notoriety as the home of alt-right white nationalist groups, including those who orchestrated the disastrous 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, which left 35 people injured and one woman dead. The catastrophe prompted Discord’s young founders, Jason Citron and Stan Vishnevskiy, to purge white supremacist groups from the platform. But it has had less success in addressing another controversial set of users: people looking to buy and sell drugs. In 2020, Robin van der Sanden, a researcher at Massey University who specialises in drug dealing on online platforms, was conducting the annual New Zealand Drug Trends Survey. As respondents answered questions about where they obtained drugs, “we kept getting Discord popping up in the textbox. And we were like, ‘What the hell is Discord?’ We made it an option, and it turned out it was super‑popular.”

Since the dawn of the internet era there has been anxiety among law enforcement, parents and politicians about the “Deep Web” — encrypted sites and resources which are hidden from most regular internet users and often used for criminal purposes like drug dealing, gambling, child pornography and human trafficking. Discord, which is being used for at least some of those purposes, is not part of the Deep Web. Those illegal activities have now migrated to mainstream apps and social media platforms where their sheer volume makes them difficulty to regulate. Whereas someone looking to buy or sell drugs would once have had to meet with a dealer in person or access secretive sites online, now both suppliers and customers are readily accessible to anyone with a phone and internet connection.

It’s particularly appealing to young people, for whom interacting with anonymous individuals online is part of daily life. Troy, a frequent user of Discord drug servers, told me: “The most populous demographic on there is university students trying to pay their tuition.”

But the deceptive ease of buying drugs online can mean customers are unprepared for the violence native to a drug system dominated by gangs and criminals. Carl, who dealt methamphetamine for the Mongrel Mob as a teenager, said the app “allows Jessica from the suburbs, who’s never met a Maori guy in her life and lives in Ponsonby, to get $50 from her dad’s credit card and put up a post on Discord. She knows she doesn’t have to be friends with these people. She doesn’t have to socialise with us. She just puts up a thing, she gets it, it’s that easy.”

He laughed as he summed it up. “The people doing it are the kids of the people who are going to be reading your article.”

Scott started dealing drugs when he moved to Auckland for his first year of university. A party boy from a privileged background in Wellington, he fell into using MDMA when he and his friends from his hall of residence went out to nightclubs. The pills provided an extra burst of pleasure and energy. Among his group of friends, using MDMA was almost as common as smoking weed.

But it was expensive, especially for students on a budget. “I figured out that if I bought just a little bit more — a gram or two — then I’d get it cheaper, and I could sell those caps to my friends for $30, rather than us all paying $40,” says Scott. “From there, word just got out a bit through people at my hall that they could get stuff off me. It got bigger and bigger, until I was buying relatively large quantities at a time and making quite a bit of money.”

At first, Scott was careful to limit his customers and suppliers to friends and acquaintances. This model has traditionally been the norm in New Zealand’s drug scene: small-time dealers buy stock from larger suppliers, usually gang-affiliated, for a limited circle of customers whom they know and trust.

When Scott moved back to Wellington after graduation, however, he found the drug scene there had transformed in his absence. In 2018 loose online marketplaces had begun to sprout in Facebook group chats. Soon they spread to other social media sites: a report last year on The Spinoff detailed a thriving trade on Instagram.

While those social media apps were — and remain — popular, there was an obvious drawback: “You were using your actual Facebook account. It was way easier to see who you were talking to,” explains Troy, who was involved with the early online marketplaces. So many of the most prominent users turned to Discord.

Many sellers offer to deliver straight to their customers’ doors: users compared the service to Uber Eats.

After Scott got back to Wellington, a friend sent him a link to one of the capital’s nascent Discord drug servers. It was a revelation. “Everyone relied on their reputation, and you had to get verified once you were in by another member,” he says. “You knew that if you rocked up to buy whatever, it was going to be good quality, and on weight, and a fair price. Just an easy transaction. It all started out, in the first few months, perfect. You’d pop up on the messageboard and see who’s posted recently, then you’d message them and drive over and meet them. It all took about 20 minutes, start to finish.”A Discord spokesperson emphasised that the platform “has zero-tolerance for illegal activity on our service . . . When we become aware of illegal activity we take immediate action, including banning users, shutting down servers, and when appropriate, engaging with the proper authorities.” But over the last few years, that zero-tolerance policy seemed to be missing in action.

In New Zealand — for reasons which remain unclear — the rise of Discord’s drug servers has largely been a Wellington phenomenon. Some dedicated servers exist in other urban centres, like Auckland; a few larger servers have channels for areas like Waikato and Nelson. But, according to van der Sanden, unpublished data from early 2020 indicated Wellington had as many as six times the percentage of people using Discord for drugs as other regions. Sarah Helm, executive director of the NZ Drug Foundation, also thinks the Covid-19 pandemic played a role, with lockdowns driving people online.

Discord “burst on to the scene quite quickly”, says Scott. “Suddenly everyone was sussing off Discord. Friends of mine have come up from Dunedin to stay, or visit in Wellington, and have wanted to buy some weed quickly. I’ve jumped on my phone and basically ordered it to my door . . . In Dunedin that’s not really a thing.”

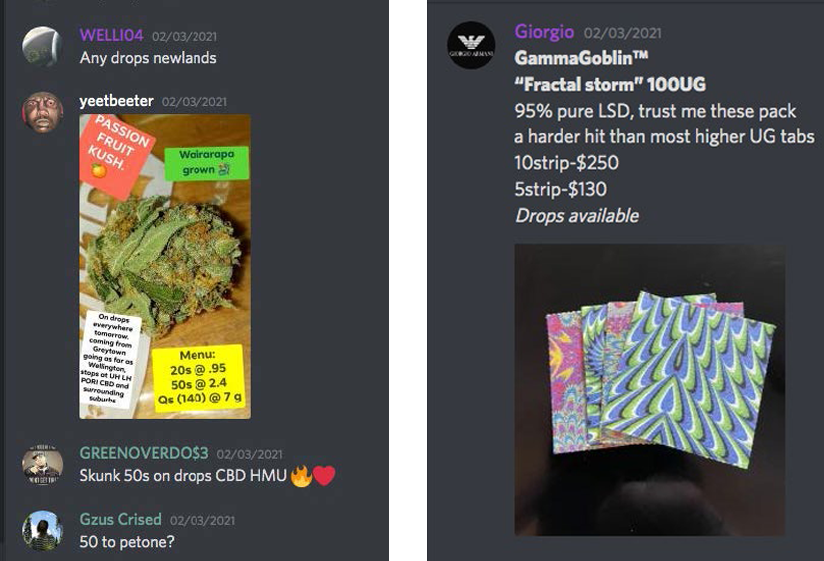

Scrolling through Wellington’s larger servers is the digital equivalent of wandering through a grand bazaar. On Welly Products & Services, a dealer with the username Mr.Thc posts a photo of a hand holding enormous cannabis buds, promising “QUALITY SOUR DIESEL”. Yeetbeeter advertises his Wairarapa-grown “passionfruit kush” at discounted prices. TheRealCa$per is notorious for running promotions: in one emoji-laden post, he congratulates two lucky winners who have won grams of flavoured cannabis and “Golden Teacher” psychedelic mushrooms. “Well done guys! Trap safe.” Hoping to take advantage of the cravings customers might experience after getting high, loveguru is selling chocolate banoffee desserts.

Harder drugs are being sold too. On Welly A+, MansaMusa posts pictures of bearded, steampunk frogs made from hundreds of tabs of LSD, promising “Quality Guaranteed Trips”. Sugarsean is direct: “Charlie. Coca. Cocaina. Whatever you call it I got your sugar fix.” He’s asking $350 a gram. In an “Easter giveaway” on another server, one entrepreneurial user advertising “50s” (bags of approximately three to four grams of cannabis) says that “Each 50 purchased is an entry into a random prize draw”. The reward? “ 1/4 gram of Pure Speed!”

The marketplace isn’t limited to conventional recreational drugs either. Adhdboi advertises instant-release dextroamphetamine tablets at $2 per milligram: typically prescribed for ADHD and narcolepsy, the stimulant can cause death, stroke or heart attack if misused. Giorgio is selling grams of ketamine, a veterinary anaesthetic which can cause convulsions, comas and near-death experiences if a user overdoses. Many offer to deliver straight to their customers’ doors: people I spoke to compared the service to Uber Eats.

Some say dealers are selling their goods at cheaper prices than they would otherwise. “Before Discord I knew people around Wellington who I could go and buy off. But it was always more expensive, because they could set their own price,” says Scott. “Whereas on Discord, if you’re in a chat with ten dealers, all selling the same thing, all posting saying what their prices are, it forces them to drop their prices. If someone’s selling for $2,000 an ounce, and another guy is selling for $2,500, nobody’s going to buy off the guy selling for $2,500. Everyone drops their price and tries to get lower than the next guy to get more business.” In other words, Discord helped regulate the black market by allowing traditional economic principles like market competition to take root.

A police spokesperson refused to comment specifically on questions about Discord, but noted: “Organised criminals go where the customers are, and use all the same technology and social media platforms that we use every day.”

As Discord’s sleek marketplaces attracted more customers, new drug dealers were forced to make the transition online too. It was a shift which many dealers found disconcerting. I first met Carl at university while we were both undergraduate students. He’d grown up in rural New Zealand and became a methamphetamine addict at age 16. To feed his addiction he worked as a dealer himself. “I got into the gang scene with the Mongrel Mob. Where I’m from, that’s where you go if you want to sell drugs.” He’d purchase a few grams of meth at the discounted price of $800 from the Mob’s local sergeant-at-arms. “He’d then expect me to on-sell that and pay him back within two days. The way to do that was to essentially split up that one gram into points of a gram, and sell those each for $100 . . . But then he’d tick me again, and it’d keep going round.”

Carl usually scraped together enough to pay for food and a few grams for himself. In a world where miscalculations inevitably led to violence, he developed an eye for unreliable customers and learned the dangerous intricacies of dealing with his suppliers in the local Mob. As much as was possible, he built trust with those he worked with. To do so, he felt he had to talk to people eye to eye. “It’s very physical, it’s very tactile, it’s very obvious. It’s visual.”

Then he moved to Wellington and found that to sell drugs, he needed to get on Discord. Now he was interacting with people he’d never met before and likely never would again. “[Discord] flips the traditional model on its head, big time,” he says. “There’s an innate trust you have to have on Discord, which I don’t have.”

One user I reached out to responded: “Bro you shouldn’t be asking me. I legit roll people and rob them :-D”.

The close-knit structure of the servers which first attracted Scott turned out to be short-lived. While stringent entry requirements and verification processes minimised risk, it also minimised opportunity. As a result, soon after Scott started getting involved, some servers opened themselves to anyone who could scam an invitation. According to Troy, it wasn’t long before they began to be infiltrated by “less than savoury characters”, many of them gang-affiliated.

“You always think, when you do get ganked, you’ll see it coming from a mile away,” says Troy. “It’s always, nah, you gotta be an idiot to fall for that.” But then he set up what seemed like a typical deal. He got into the car and found his contact plus “three of his bros wearing Black Power patches”. His contact pulled a knife out and held it to Troy’s throat to force him to hand over the money. In Welly A+, the server’s administrator posted at one point, “Just a heads up and a wake up call for everyone, I got a gun pulled on me last night for two ounces stay safe out there fam and if it seems dodgy don’t do it.”

“People had been having knives pulled on them, having their money stolen, been beaten up,” says Scott. At first he ignored the reports, thinking it would only ever happen to other people. Until, of course, it happened to him.

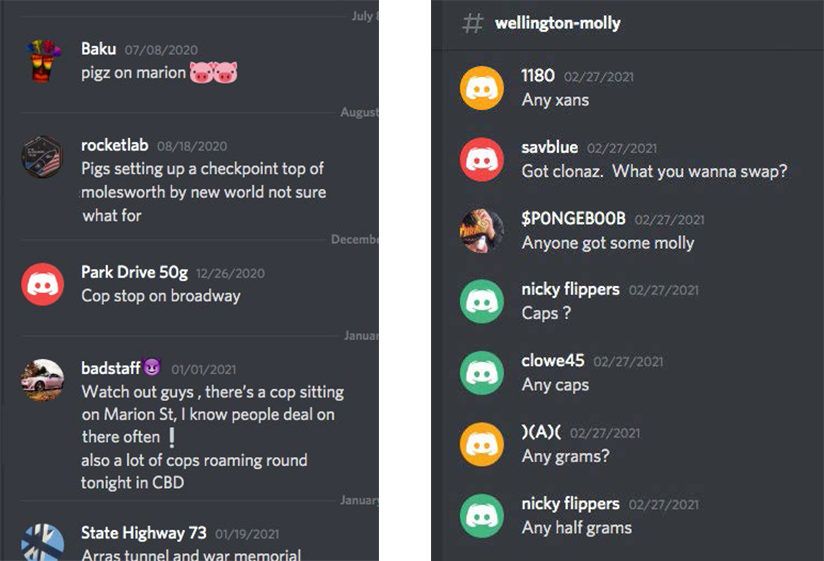

By the end of 2020, news reports began to appear on Stuff about “attacks [which] appear to involve the use of the app Discord and offenders believed to be gang members”. Police pleaded with victims to come forward. In one article Detective Sergeant Steve Wescott emphasised that “the most important thing is that the serious offending is addressed and that we prevent further harm to others. If someone is offending against you, they may be offending against others.” He noted that police could use their discretion not to prosecute low-level offending, if it led to proceedings against more serious criminals.

For most Discord users, says Troy, this was obviously out of the question. “You can’t call the police, because you’re buying drugs.” Instead, most servers set up channels where users could complain about bad deals, warn about particular dealers and remind users to be cautious.

But on a platform which prioritises anonymity between users, accountability was all but impossible. “Obviously the guy who had just been called out would then delete the account straightaway, make a new one and be back within ten seconds,” explains Scott. “Nobody would make the connection that it was the same guy.”

It was a dilemma I experienced while researching this article. One user I reached out to responded: “Bro you shouldn’t be asking me. I legit roll people and rob them”. Their username subsequently went dark..

Most Discord users believe that violence is largely being perpetrated by members of the Nomads gang, though nobody I spoke to could provide firm proof. One of the most prominent Discord users in Wellington, whose nicknames are always a variation of ‘Wellington District Police’, began to wage a verbal war against users he suspected of being gang members. He encouraged customers and dealers to set up new servers to try to purge bad faith members. Since he is also the administrator of his own private server, many of his warnings come with an invitation to join his marketplace, where he sells cannabis and a handful of harder drugs.

But according to Troy, when the Nomads saw Discord users fleeing to new servers, they simply set up their own. “There’s a server, Dr Green’s Happy Company. That was created by them. They’d figured out what everyone else was doing: creating new servers in order to keep moving. They created one of their own, sent the links out, and anyone who messaged in, they’d use their own accounts to hit you up, and then rock up on you and put a knife to your throat. And what are you gonna do?” Van der Sanden has also found servers connected explicitly or implicitly to particular gangs and gang-affiliated individuals. She says some even use a particular gang patch as their server’s identifying icon.

This wave of criminal activity on Discord, sometimes connected to organised criminal groups, is not unique to New Zealand. Overseas media outlets have reported that the platform is being used for everything from identity theft to grooming children for abuse and exploitation. And while Discord has been willing to hand over user data when approached by overseas law enforcement like the FBI and shut down servers identified as havens for illicit activity, those overseas media outlets reported that new criminal accounts and servers have popped up just as quickly.

Since Scott’s mugging last year, he says he hasn’t used the app. “I said to myself, I’m never getting back on this app. I’m never buying any drugs again off Discord, regardless of whether it’s $20 or $1,000 dollars’ worth. I’m completely done.” Most of his friends have switched back to buying from people they know personally, he adds. “Everyone’s a bit more worried about it now.”

Last October, an email pinged into my inbox from Discord’s Trust and Safety Team. “Discord is focused on maintaining a safe and secure environment for our community,” it read. “Your account promoted or encouraged illegal activities, including but not limited to providing a marketplace for or facilitating the dissemination of regulated goods, or participating in servers dedicated to doing so.” The account I’d been using to research this article was disabled; so were the accounts of van der Sanden and the users I’d spoken to. A massive purge was under way, with countless servers shut and users banned.

But they couldn’t catch everybody. Some servers escaped the purge; others were established in the aftermath. People created new accounts and logged back on. “It wouldn’t surprise me if rates of using Discord decline a bit, just because people are nervous,” says van der Sanden. Those users might move to more secure encrypted messaging apps like Signal and Telegram.

But many others are committed to buying and selling drugs via Discord, and comfortable with doing so despite the dangers. When I asked Troy if he still uses the app, he said he was “trying to get out” but admitted he hasn’t stopped completely. “Sometimes you need those scores.”

“Discord’s huge. It won’t stop now. You can’t police it,” said Carl. “It’s everyone. It’s the people you least expect.”

Pete McKenzie is a freelance journalist based in Wellington, where he focuses on politics, foreign affairs and legal issues.