The Forever Files

From the age of 18 to his retirement at 65, Wellington GP Dorian Saker was a watched man. Driven by Cold War insecurities, our security services spied on Saker and his friends, a group of young professionals whose ‘crimes’ were to be thinkers, socially conscious and . . . not much else.

By Nicola Saker

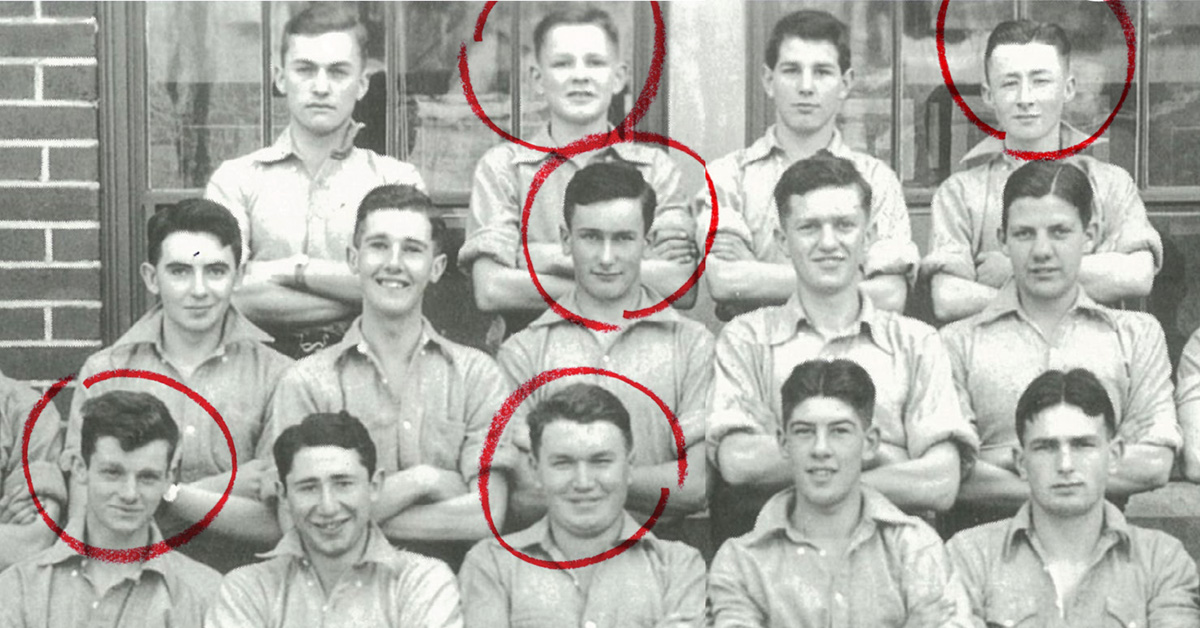

Where it started: Class 6A at Wellington College, 1937. Dorian Saker is first on the left, front row. His friends and Vegetable Club attendees later spied on by Special Branch were future geophysics professor Frank Evison (back row, second from left) and Dick Collins (back row, far right), whose diplomatic career would be stymied. Also watched were lawyer Keith Matthews (middle row, fourth from left) and sociology professor John McCreary (front row, third from left).

Some two decades after my father’s death, I applied to the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service for his file. I was motivated by curiosity — how much of the banter between him and his friends about being spied on had been true? Seven weeks after my request, I received a bulky package, some 25 pages in all. The covering letter from Rebecca Kitteridge, SIS directorgeneral of security, stated:

I do request, as you read the material we are making available to you, that you bear in mind that the information on your father’s file is close to 70 years old, and written in a different era. Some of the reported comments are indeed personal opinions reported at the time by old Special Branch officers. I trust the information released to you does share some interesting insights into your father’s past.

Well, yes, it does share some “interesting insights” into my father’s past: his early literary endeavours, an insouciance easily mistaken for lack of seriousness (when asked by the SIS if he’d ever been into the Soviet legation, he said no, but that he “understood they served some very good vodka”) and most of all into his talented, loyal, passionate and free-thinking group of friends.

Other more surprising insights reveal the dangerous incompetence of the precursor to the SIS, the police’s Special Branch, and the refusal of the SIS over the past 70 years to make any acknowledgement of the wrongdoing and harm done by its predecessor — particularly as regards the invidious episode of the ‘Vegetable Club’. The director’s letter contextualises the situation and it almost sounds like an acknowledgement, but it’s not.

Formed in the early 1950s, the Vegetable Club consisted of my father, many of his friends and some of their acquaintances. They gathered, they talked, they drank beer and sometimes discussed world affairs. They did nothing illegal. It wasn’t, and still isn’t, a crime to hold views that challenge government policies. Yet in our state’s misplaced zealotry, its security agency behaved exactly as did the ideologues it was purporting to vanquish: it suppressed loyal dissent; surveilled innocent citizens; and accused civil servants of disloyalty based on little more than speculation and gossip. Those accused had no idea they were being watched, what they were accused of or by whom. And they had no right of reply.

No one died, attempted suicide or suffered a mental breakdown as a result of this surveillance. But the diplomatic careers of two talented young men were quietly snuffed out based on fact-free and ignorant suspicions. They weren’t denounced, as that would have required logical explanations, tangible proof and revealed the surveillance. Instead, it was made crystal clear to them that their careers would go nowhere. They resigned.

The dossiers compiled during the surveillance were (and are) like forever chemicals, those that linger in the environment without breaking down. They are ‘forever files’, and when asked for them, the SIS spends weeks to months redacting information and controlling the release process. If, as the director says, they are historic and no longer reflect the culture of the SIS, what’s the problem?

In what is a now-familiar narrative to those of us who have sought our parents’ files because of this episode, this is the gap they shoot: “That was then, this is us now, nothing to do with us, long time ago, it’s different now.” Except it’s not, is it? Learning from mistakes usually involves acknowledging the mistakes.

I understand it was a different era. But as William Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Until there is some acknowledgement of responsibility or, at the very least, regret from the SIS, the sense of injustice will live on.

Left — The young Dorian Saker. He studied classics before qualifying as a doctor after the war. Right — With his best man at his 1948 wedding, school friend Nigel Taylor.

My father, Dorian Saker, has the dubious distinction of coming to the attention of Special Branch earlier than many of his friends who were involved in the Vegetable Club episode because of a piece of fiction he wrote. Victoria University’s student paper, Salient, published “There’s a war on . . .” by Michael du Fresne in June 1940. Michael du Fresne was a pen name used by my father, who was the literary editor of Salient. Here it is in its entirety:

So, there’s war on? No, you don’t say. Who could have told you that now? Ain’t it just too bad, and what’ye going to do about it, sonny? Ain’t it just a nice time for getting into that pretty uniform?

The newcomer looked sheepish. He was fresh from the country, with a glow like a ripe Jonathan in his cheeks, and his eye liquid like sun on the water. I came to get a job, he said. Wanta get into a factory.

You go and join up, boy. Don’t you know there’s nothing better than fighting for your country? Look at Harry over there — see his arm. His King and country took that. He leaned over and whispered in the boy’s ear. Maybe you’ll get something like that.

And Jim the wit said. If you want kids, have ’em before you go. These new bullets make a hang of a mess. I know a chap had his doings blown clean away.

The boy blushed.

He doesn’t want any kids. He couldn’t even if he wanted ’em! He’s not old enough!

What’s the pay like? said the boy.

Swell! they said. Nine bob a day, an’ you can’t spend it. Can you beat that now? Hey! Here’s the recruiting Sergeant come for a drink. Here’s a chap for you, Sarge!

Wanta join up, lad? Good pay, good meals, good friends, and fine clothes — best in the country! Anyway, let’s have a drink . . . and the same again.

Name taken, address, everything; he couldn’t escape. O.K. — he was in the army. He still looked a shy country boy.

They said Hell! Wait till you’re out in the trenches; then you’ll have some fun.

But Jim the wit said: Better have some before you go son! They’re dirty bitches out there.

The Barman said: Good luck, boy — give ’em my love!

The veteran said: Give ’em what we gave ’em in 1914

He said, I was going to get a job in a factory; seems I’ve got something different. S’ppose I’d better to write to ’em at home. Mightn’t be seeing them for some time.

Pick up your traps, blast you! the sergeant said . . .

It is mainly remarkable for its economy. Yet this piece, written by an 18-year-old first-year arts student, was read by Special Branch and deemed subversive under the Public Safety Emergency Regulations and indecent under the Indecent Publications Act. They brought it to the attention of the attorney-general, Rex Mason, whose permission was needed for a prosecution. Mason agreed with the police assessment and booted it upstairs to the prime minister, Peter Fraser, for appraisal.

The editor of Salient, Maurice Boyd, and the president of the Students’ Association, Ron Corkhill, were summonsed to a meeting with the PM and attorney-general. Corkhill defended the story’s publication, saying “at the time of accepting it [there was] no thought of the article being subversive or indecent” and that it was “published in good faith and purely for its literary merit”.

Fraser disagreed and suggested the author of the article should resign as literary editor as he was not fit to occupy the position. It was noted the author was only 18 and just beyond the Children’s Court.

The outcome was that my father agreed to resign from Salient, Corkhill agreed to take responsibility for the paper in the future, and Fraser agreed he would recommend there be no prosecution. Fraser’s decision not to prosecute can be seen as somewhat sympathetic, given that he spent a year in prison in 1917, charged with sedition for his views opposing conscription. Equally, though, surely a truly sympathetic response would have been to waive the entire episode as youthful misadventure?

And that was that. Except it wasn’t. The above affair comprises only the initial pages of my father’s SIS file, which, once started, continued to expand during the following decades, along with those of his closest friends.

Given the cynicism about war in his story, it is worth noting that the same year, 1940, Dorian enlisted in the army, trained for a year at Waiouru and Carterton, then served with the 3rd Division in New Caledonia for almost two years. He worked as an orderly in the field hospitals near Bourail and, possibly inspired by this experience, after the war was accepted into medical school at the University of Otago, where he completed his degree in medicine in 1951.

Left — The wedding party: Saker, bride Gay Nimmo, bridesmaid Jill Stacey, best man Taylor. Right — VE Day celebrations in Wellington, 9 May 1945. Saker (with pipe), Nigel Taylor and Keith Matthews (at rear). Photo: John Pascoe.

There is a photo of class 6A at Wellington College, 1937. There is my father with the young men who became his lifelong friends: Richard Collins, Keith Matthews, John McCreary, Frank Evison. Along with Nigel Taylor, who was in another form, they were the genesis of what became the Vegetable Club.

After Wellington College, they went to Victoria University College, as it was then. My father studied Latin and Greek and became a junior lecturer with the prospect of an academic career; Collins, Matthews and Taylor studied law (Collins then chose a career as a diplomat); John McCreary went on to become a professor of sociology; and Frank Evison became a professor of geophysics, specialising in earthquakes. He was in the right place for it — and the earthquakes weren’t only of the seismic kind.

Like my father, many of his friends served in the war. Nigel Taylor was alongside him in New Caledonia. Dick Collins served with the Divisional Cavalry throughout the Italian campaign and was helpful to the ‘Monuments Men’ when he recognised and saved a Botticelli from a villa he was liberating. These were not people who, when the call came, turned it down. If, like conscientious objector John McCreary, they did, they owned their beliefs and endured the consequences.

Two catastrophic world wars, with a global economic depression in between, created a cynicism about the old order and a sense of urgency about the need for new thinking. These young people were determined not to be like their parents. After demobilisation, they picked up their disrupted studies and careers and created an extended family structure among themselves — living in the same neighbourhood in Wellington (Thorndon), some sharing houses; sharing childcare when that became required; and profoundly enjoying each other’s company and conversation.

They were bright, well-educated, witty, energetic, and young. What could possibly go wrong?

The World War II alliance against Nazi Germany and Japan, which included both New Zealand and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, was brief.

Put simply, within two years of war’s end in 1945, the geopolitical landscape had hardened into two opposing ideologies: Soviet Union-style communism and American-style democracy. A decade later came China’s cultural revolution of 1966 to 1976. By the late 60s, about a third of the globe was operating under a communist ideology which was viewed as a global threat to democracies everywhere.

New Zealand’s default position had been anti- Russian from the late 19th century, based on the somewhat imaginative idea that there was a serious threat of invasion by imperial Russia. Post-World War I, this morphed into an anti-Soviet stance with a particular focus on the domestic threat. The Communist Party of New Zealand was established in 1921 and was perceived by the authorities to be managed and funded by Moscow.

New Zealand’s role in the World War II alliance created a relationship — a massively unequal one in terms of power and influence — with the United States that its postwar governments enthusiastically embraced. Where the United States went, so did we, and when the US anti-communist crusade reached its paranoid and feverish peak under Senator Joseph McCarthy, we followed suit.

With random, unintended irony, the home of the Vegetable Club was in a building on Lambton Quay where the McCarthy Trust building now stands. It housed the premises of Duncan, Matthews & Taylor, the law firm of Dorian’s Wellington College friends Keith Matthews and Nigel Taylor. Taylor, a barrister (as well as best man at my parents’ wedding and later a judge), had acted for waterfront workers during the 1951 dispute and, in a private capacity, organised drops of vegetables to families of workers suffering privation. This was an illegal act at the time.

After the strike was broken, this evolved into a vegetable cooperative run out of the law firm on Friday nights (“certainly not the type of business which one would expect to find organised from the office of a reputable legal firm”, sniffs a Special Branch report). Pubs at the time closed at 6 o’clock, and what became known as the Vegetable Club offered beer and conversation into the evening to an array of young professionals, academics, an accountant, a land agent or two, the tailor in the building and two young diplomats: Richard (Dick) Collins and Douglas Lake. Also at the gatherings was at least one police informant, if not more.

Security in the New Zealand of the early to mid- 1950s was the province of Special Branch, an arm of the police. And provincial it was. In a later interview with writer James McNeish, Sir George Laking, former head of External Affairs, said their methods were primitive: “They had no notion how to handle these matters”. That was a very real shame, because not having a ‘notion’ had distressing consequences.

Special Branch’s methods were not only primitive but comedically incompetent. When Nigel Taylor addressed a public meeting of the Human Rights Organisation in Christchurch, a Special Branch officer was there to observe: “TAYLOR, Nigel, stated to be a Solicitor from Wellington. He has not previously come under the notice of this Special Branch. He appeared to be about 35 to 40 years of age, about 5ft 8ins in height, medium build, dark hair. This description may not be very accurate as I was at the rear of the hall and did not get a closeup view of Taylor.” With spies like these, who needs enemies?

One Special Branch informant, George Fraser, wrote a tell-all book, Seeing Red (1995). In its introduction, the publisher, Murray Gatenby, describes the author: “Fraser’s decision to embark on intelligence-gathering was mainly due to a national chauvinism, fed by the massive anti-communist propaganda circulating at the time and enhanced by religious dogma from the pulpit of his local church.He had no training in politics, lacked knowledge in the history of socialism or the rise of communism and had not read one Marxist or Leninist book when recruited by the New Zealand Police.” Tabula rasa. Perfect.

Later in the book, Fraser reflects on the effects of his spying on a group of editors in Wellington who produced a fortnightly publication called Newsquote, which reproduced articles from overseas newspapers such as the Washington Post and Wall Street Journal: “It is difficult to accept that the lives of these people were to be so affected — for bringing to New Zealanders news that was available to everyone and reprinted from highly reputable publications. But I am sure at the time I believed the magazine was anti-American (and therefore communist) . . . because I had been TOLD that it was!”

Hugh Price, who established the publishing firm Price Milburn, was an editor of Newsquote and also attended Vegetable Club meetings. He was turned down for a role in the public service as a security risk. In the epilogue of Seeing Red, Price writes that George Fraser “came to see” that “people he was spying on were far from being the sinister forces planning subversion and espionage, but instead were decent, generous New Zealanders who were in no sense agents of any foreign power and who were as patriotic (with rather different emphases from the RSA king-and-country SIS patriotism) as anybody else”.

Fraser was sent to monitor the Vegetable Club gatherings as well as the Newsquote editors. According to my father’s SIS file, informants were planted because: “It is . . . well known that Communist Parties engage in illegal, as well as legal, activities and particularly in countries where the Party is itself illegal, arrangements are made for members to meet under the guise of belonging to innocuous clubs and societies such as drama groups, discussion and debating clubs and the like . . . Consequently, this ‘Vegetable Club’ which is a rendezvous for leftist intellectuals might conceivably be organised for some more sinister reason, although there is no information at present available to suggest that this is so” (italics mine). And no information or corroborating evidence was ever produced.

The author of one informing report frets: “The distribution of vegetables is an excuse for a social evening where a fair amount of liquor is consumed, resulting in members leaving the premises in various stages of intoxication.” Not to speak of the informant himself. In Seeing Red, George Fraser recounts: “Special Branch was anxious for me to detail the subjects discussed and the conclusions reached [at Vegetable Club gatherings] but, with a bellyful of booze and the camaraderie of the occasion, who was to remember?”

He did, however, remember enough to report that Dick Collins, during a conversation about a proposed exchange of prisoners of war in Korea, said: “There could be immediate peace in Korea, but the bloody American bastards had so many rotten dollars tied up in armaments that they would see to it there was no peace there.” He added: “Those bastards are so involved in it financially they will see to it that the Communists don’t get peace.”

In the minds of Cold War warriors, criticism of the United States meant you had to be Communist. Any dissent from the New Zealand government and its allies was intolerable, even if no action resulted from that dissent.

In more weak tea from my father’s file: [an interviewee] said: “. . . Saker . . . had radical views but [the interviewee] could not say that he was a Communist” (italics mine).

On and on it goes, the naive speculation and insinuations, without a scintilla of proof. The file attacks my father’s character but, as he was a self-employed doctor in general practice, they couldn’t attack his livelihood and career. They left that for two promising young men of the diplomatic corps.

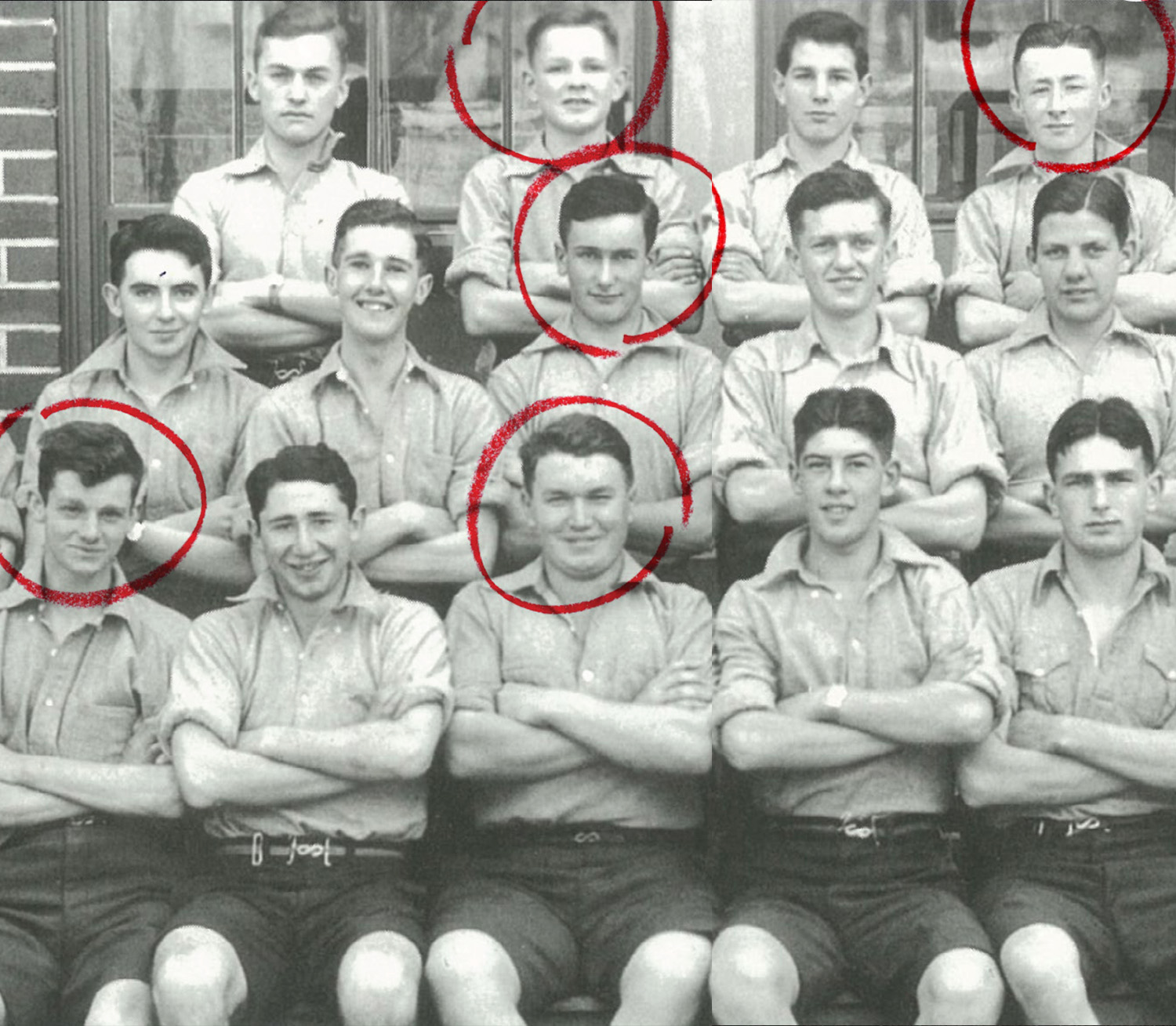

“Disreputable”, a “radical”: pages from the Saker file, including a letter sent to MI5 in London.

The Vegetable Club was not a political club, but politics were discussed, the way they are still at gatherings of all kinds in the capital. Then, as now, no doubt a fair amount of blather was talked.

But as government employees at External Affairs (the forerunner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade), Dick Collins and Doug Lake were, among all those who attended the Vegetable Club, the only ones involved in policy development and privy to information about government affairs. This gave Special Branch a lever to help the government prove that it was in step with the Western alliance on the perceived threat of communist subversion.

It also justified an inordinately expensive surveillance operation. My father’s file documents not only his attendance at the Vegetable Club on Fridays at the law firm of Duncan, Matthews & Taylor, but scores of other encounters. It records, for instance, that he and my mother visited Dick Collins on 1 February 1953 and was, in turn, visited at home by Collins on 6 May the same year from 8 to 11.30pm.

My parents are also noted visiting the law firm on days other than Fridays, and frequent visits by my father alone are recorded. This must have amounted to virtually full-time, five-days-a-week surveillance not only of Duncan, Matthews & Taylor but also several of the homes of Vegetable Club members. That’s a lot of watching.

Vegetable Club aside, one reason for my father’s frequent visits to the firm was that Keith Matthews was his solicitor, and at that stage of his life my father was selling the family’s Thorndon house, buying another in Northland, and buying a medical practice and its premises.

All this Boys’ Own surveillance had real-life consequences. Dick Collins was reported by the police informant at the Vegetable Club for his “incautious” remarks, and he ended up resigning from External Affairs. In effect, he was forced to, given that he was looking at a career with no prospects. But it didn’t end there.

Collins, reluctantly, returned to law and, to the surprise of no one who knew him, made a success of it. In the meantime, the fanaticism of the Cold War warriors continued. In an interview with Sir George Laking for his book, The Sixth Man — an account of a New Zealand diplomat accused of spying — James McNeish records Laking recounting that, when he was deputy secretary of External Affairs, he was rung by the then-deputy prime minister, Jack Marshall. Cabinet was considering appointing Dick Collins to the High Court — but wasn’t there something untoward in his background? Dick Collins wasn’t appointed. So, not just a single career was scuppered but the apogee of his second career was too.

Quite apart from the fact that a purported indiscretion of 15 or 20 years earlier was dredged up as a reason not to appoint, this event points to a jarring and significant issue of constitutional impropriety. Cabinet does not appoint High Court judges, the attorney-general (then Ralph Hanan) does. Cabinet should merely note the recommendation of the attorney-general. This is to prevent exactly what happened in this case — political interference in the judiciary.

Doug Lake was the other diplomat affected by heavy-handed surveillance. Lake had an impressive war record. Initially a journalist, he joined General Bernard Freyberg’s mobile Middle Eastern headquarters as a clerk. At Belhamed Ridge in Libya in November 1941 Freyberg’s HQ was surrounded by Rommel’s panzers and it was Doug Lake who put pedal to metal and drove the general to safety. He was then seconded to Moscow to help set up a New Zealand legation and it is there that he met his future wife, Ruth Macky. Ruth was from Auckland, a gifted student of languages, which led her to be employed by the government as a support person in its diplomatic missions.

They married in Moscow, started their family there, and returned to Wellington where Doug was welcomed into Alister McIntosh’s newly minted External Affairs as “an extremely able officer”. The Lakes’ time in Moscow and their interest in it led them to join the New Zealand Society for Closer Relations with the USSR, and it was a pamphlet written by Ruth Lake, recounting her time in Moscow and rebutting criticism of the USSR, that first caused Special Branch to finger Doug Lake as a communist. Alister McIntosh, understanding the threat to Doug’s career, asked him to try to stop her from publishing it, but “I had too much respect for my wife as an individual to attempt to overrule her”, he said later. As McNeish writes in The Sixth Man, “Lake’s crime was that he respected his wife”. His visits to the Vegetable Club did not help matters. Lake was told by McIntosh that he could stay in the department but there would be no overseas postings as the police and its Special Branch had to vet overseas appointments. He resigned in 1954 and couldn’t find work until McIntosh helped him get a job at the Press Association. In 1962 he, Ruth and their three daughters moved to Beijing, where he worked as a language “polisher”. The family returned to New Zealand in 1968, but employment commensurate with his education and experience was again closed to him. He went to work as a storeman.

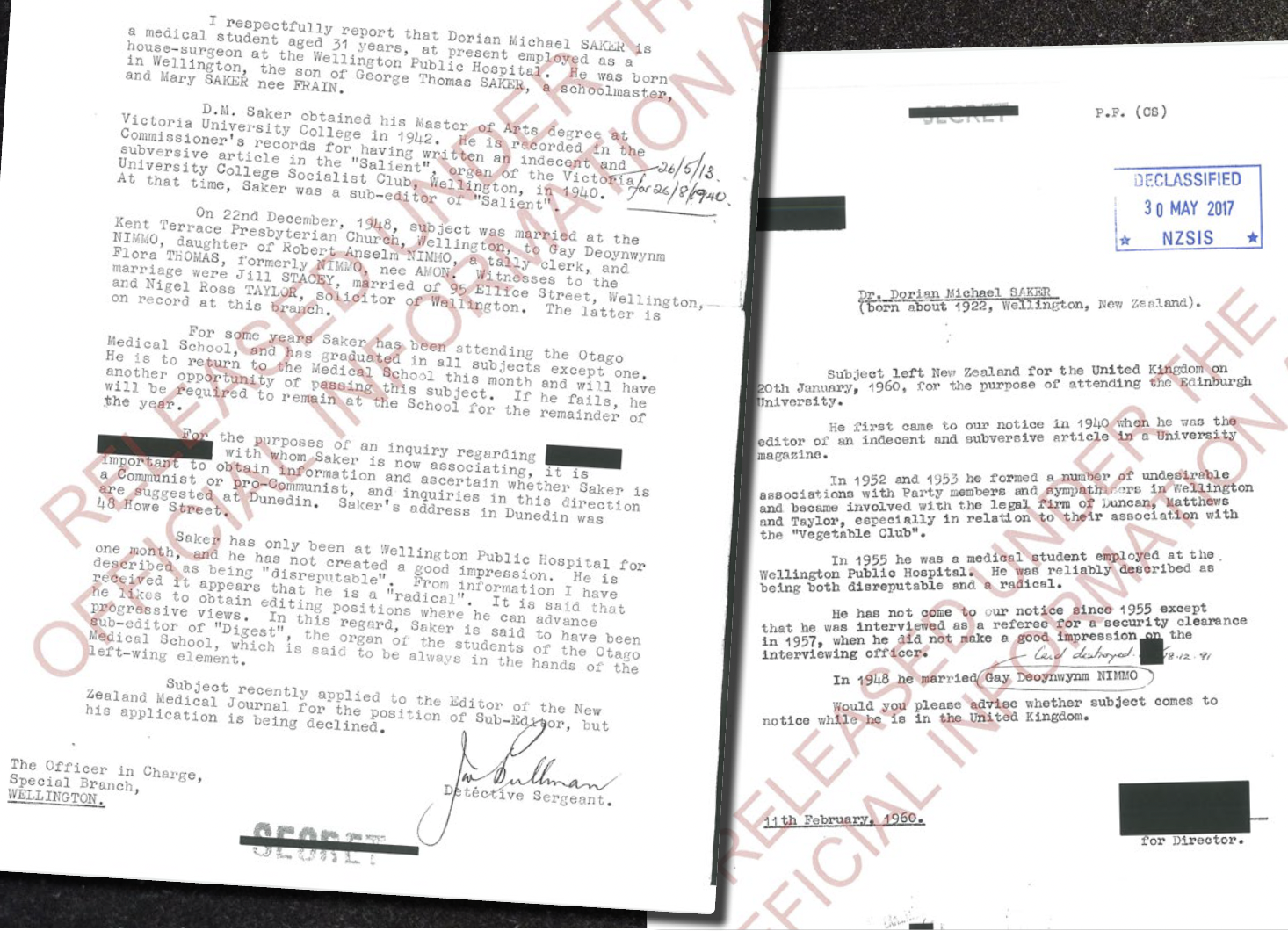

From left – Family man or dangerous subversive? Saker outside the family’s London home with a neighbourhood child, far left, and the Saker kids from left, John, Tim, Kerry & Nicola. / Lawyer Dick Collins (at top). / Dorian in midlife.

Children and grandchildren of Vegetable Club members still meet, monthly, at the Wellington home of Jackie Matthews, Keith Matthews’ 95-year-old former wife. Now, as in its heyday, politics along with many other topics is discussed. Jackie enjoys mulling over Vegetable Club matters and is the sole remaining witness to those events.

Unlike Dick Collins and Doug Lake, my father’s life was unaffected. Yet it is still a shock to read his SIS file and discover that in 1960, when our family went to live in London for two years, a letter was sent to MI5 asking them to “please advise whether subject comes to notice while in the United Kingdom”. This was based on the Salient article, the Vegetable Club, and being “disreputable” (quite how this manifested itself is never conveyed) as a house surgeon at Wellington Public Hospital. Equally surprising is that his second marriage, in 1978, is deemed worthy of note, almost 40 years after that Salient article.

Nigel Taylor, also unscathed, went on to become a judge. It seems unlikely he stayed awake at night due to the commissioner of police scuttling his application in 1961 for a warrant to become a scoutmaster: “This Service cannot recommend the appointment of Nigel Ross TAYLOR.” Who knows what impression an articulate, amusing, imaginative and community-minded lawyer might have had on the Boy Scouts?

Dick Collins’ family are the ones most affected. All four of his children have lived abroad since early adulthood and at least one of them gives their father’s experiences as the reason. After their mother’s death, an intermediary acting on their behalf requested from the current director of the SIS an acknowledgement of wrongdoing. This was denied with the now-familiar response: ‘It was historic, there were different attitudes and procedures then, it is different now.’

It may be historic but now, more than ever, it is recognised that historic wrongs require righting even if only to the extent of acknowledging that wrongs occurred. While not a remedy, an acknowledgement of the moral injury of past practices would be a salve to all those concerned. As military historian Aaron Fox writes: “The legacy of New Zealand’s domestic experience of the Cold War remains like a long black cloud over the nation’s recent history. Once-secret files and published memoirs display the personal qualities of these talented New Zealanders who ran foul of the state after 1948: intelligent, ideologically committed, yet independent thinkers, not afraid of voicing their opinions or associating in public with like-minded people, whatever the professional and personal costs of such actions. The declassified files also reflect poorly on those who were charged with the protection of western and domestic security and could determine that individuals were security risks even when the results of close surveillance indicated otherwise.”

New Zealand’s security service wronged these people. Its actions caused direct harm to the lives of some Vegetable Club members. More widely — perhaps more subtly and insidiously — its actions affected the confidence of all Vegetable Club members who believed passionately that New Zealand, was, and must remain, a free and just society. The harm lingers, as many of the next generation of Vegetable Club members note the absence of an official acknowledgement of wrongdoing.

Others have attempted to right the wrong: Alister McIntosh continued to advocate for Dick Collins’ exoneration; Sir David Beattie, on behalf of the judiciary, campaigned to have him appointed to the High Court. Others have also sought remedy only to be met, over seven decades, with silence, obfuscation and wilful blindness.

The ‘that was then, it’s different now’ feint doesn’t really cut it. Special Branch was in charge of national security, as is SIS. No other agency is relevant to this history. Isn’t it time the SIS owns its past, however unsavoury, and reconsiders its position regarding Dick Collins and Doug Lake in particular, and all the others? If they want to underline how different they are, what better way than acknowledging the injustice? Until this happens, key democratic principles we hold dear — freedom of assembly, association and speech; inclusiveness and equality; the rule of law incorporating natural justice; citizenship and the consent of the governed — continue to be undermined by its attitude.

Nigel Taylor sums it up in his submission to the parliamentary select committee on the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service Bill in 1969: “These [submissions] are a plea for an open society, for the maintenance of a society whose values are the antithesis of the ones we are trying to protect ourselves against. If we are going to behave like Communists, or like to think Communists behave, what is the use of protecting ourselves from their evil designs?

“The only protection of an open society is a robust freedom where no man fears his fellow, and where the treachery of one’s apparent friends is unthinkable.”

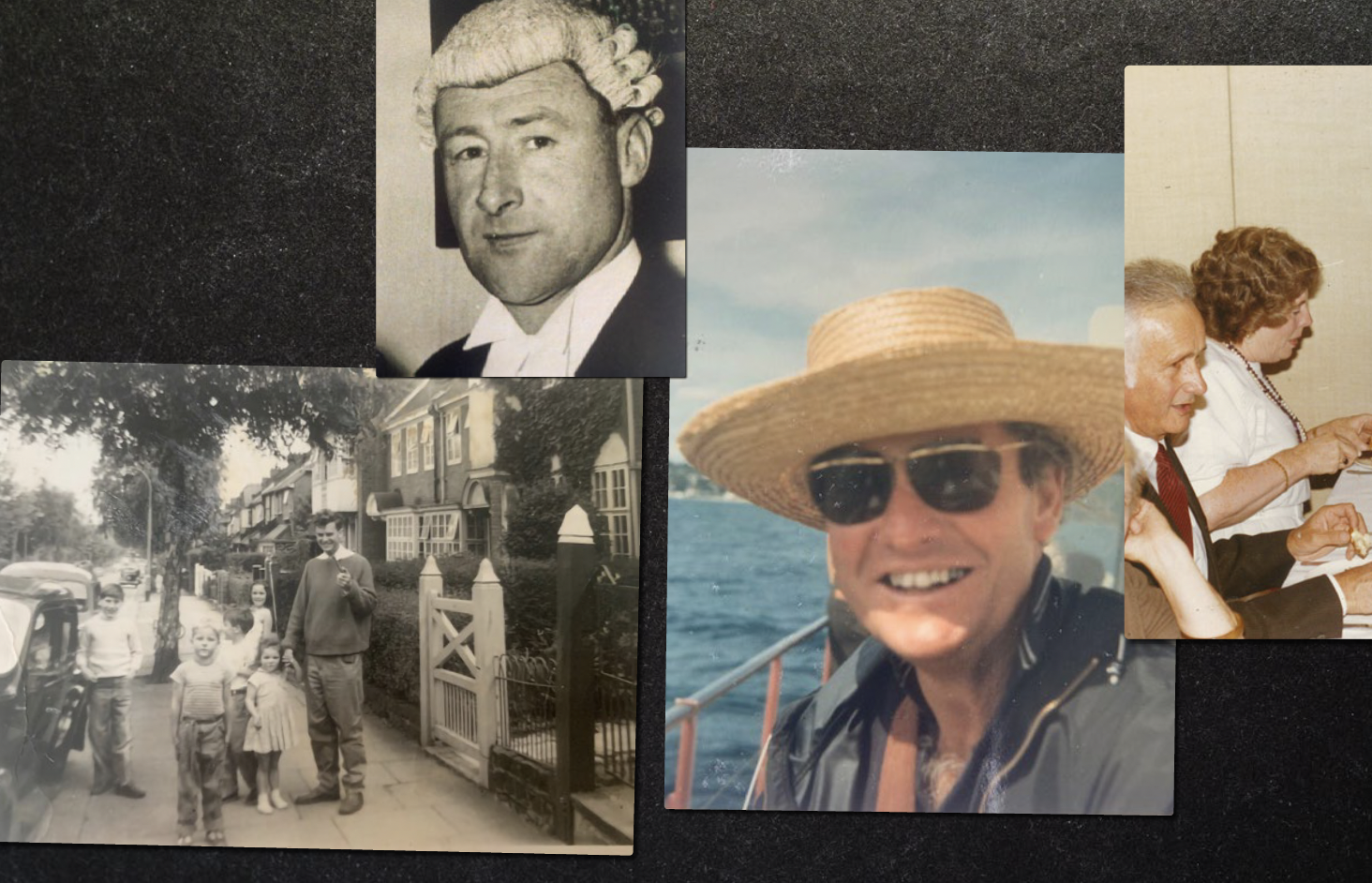

The connections stayed strong. In 1985 they gathered for Nicola Saker’s wedding. Around the table, left to right, Keith Matthews, Barbara Collins, John Scott, Jackie Matthews, Dick Collins, Marguerite Scott. / Dick Collins, Gay and Dorian Saker.

Nicola Saker is a Wellington based writer and journalist. She has published several books including Woman in Love: Katherine Mansfield’s Love Letters. She is president of the Katherine Mansfield Birthplace Society.