The

Unhappy

Valley

It’s bloody paradise, it’s a nightmare, it’s a bargain — the residents don’t agree on much, except that Waipori Falls is unlike anywhere else in New Zealand.

By George Driver

Not many people find Waipori Falls by accident. But Daniel Williamson did. About seven years ago, he was driving back to Dunedin from Central Otago with his wife Kate when they took a wrong turn. Climbing a jarring gravel road through a forestry block, they came to a lake wedged into a valley in rolling tussock high country and zig-zagged down into a steep forested gorge.

“Then, out of nowhere, there was this village in the bush,” Daniel recalls — some 33 houses practically stacked upon each other, lining three private roads wrapping around the gorge. “It was beautiful, but quite unusual, even for New Zealand.”

Surrounded by a Department of Conservation reserve and looking on to a waterfall cascading down a 200-metre rockface, Waipori Falls resembles a transplanted patch of Fiordland between the green farmland of the Taieri Plains and desert-like Central Otago. It’s 40 minutes from Lawrence and 50 minutes to Dunedin, with winding corrugated roads in either direction. Not many people drive these roads anymore. Not even cellphone reception reaches Waipori Falls.

About six months later, Daniel, then 37, and Kate, 42, were scouring Trade Me for a rung on the property ladder when they saw a cheap house with an incredible view. After getting in touch with the real estate agent, they realised it was in the same almost-forgotten town they’d stumbled across.

They bought the house, a 1920s two-bedroom weatherboard cottage — hardwood floors, high ceilings, an open fireplace — for $80,000. The price wasn’t an anomaly. Waipori Falls may be the cheapest place to live in New Zealand. Fifteen houses have sold in the village in the last five years, and none have gone for more than $200,000. In June last year, a three-bedroom sold at auction for $75,000 — a local said there was only one bid.

For Kate, an artist, it was an opportunity to paint in solitude in a scenic location. Daniel, an aspiring writer, wanted time to spend on his horror fantasy novel. They felt, Daniel says, like they’d purchased “a little piece of paradise”.

Not long after the couple moved in, they went along to the annual general meeting of the local body corporate. This is another feature that makes Waipori Falls atypical. Unlike almost every other town in New Zealand, the infrastructure is not owned or run by a local council. There’s no mayor or councillors to make decisions. Instead, a body corporate committee and a chair are elected each year. In Waipori, your neighbours set your rates, ensure your drinking water is clean and keep your toilets flushing. It’s politics at its most personal; local democracy at its most extreme.

The Williamsons didn’t know much about this when they bought the house, and so they thought the AGM would be a good chance to get to know their neighbours. Instead, they walked in to watch the 18 attendees split into two warring factions and yell at each other for the next six hours. The chair accused the former committee of corruption and quit. Then the entire committee resigned, too. “We didn’t really understand what it was all about. Why is there that much animosity?” Williamson says. “We later got told most people only ever go to one meeting.”

In Waipori, your neighbours set your rates, ensure your drinking water is clean and keep your toilets flushing.

When no one else wanted to step in to be the next body corp chair, Daniel Williamson put his hand up. “We’d just moved in and we loved our house and I thought, ‘This can’t fall over’.”

He soon discovered the body corporate was almost bankrupt. During a long-running fight over the levies paid by residents, the committee had racked up large legal bills. Some people hadn’t been paying for years. Williamson says the committee had dipped into its long-term maintenance fund to pay an insurance bill.

Next, he discovered the sewerage plant wasn’t working. A broken pipe meant partially treated sewage was seeping into the ground and into the neighbouring Waipori River. He managed to get the wastewater system fixed, but then a flood damaged the plant. Later, it was vandalised, and a battle broke out over how to spend the insurance payout.

Meetings continued to be fractious. Kate remembers one in which a resident insisted on “screaming” his way through 37 motions. There was the AGM where the body corp’s management company insisted on having security present. Williamson says there was nearly a punch-up before another gathering. “People came out shell-shocked,” Williamson recalls. “We proposed having our AGMs at the police station to prevent that kind of behaviour.”

One outsider who attended a public meeting was afraid for his safety. “People were storming out, people were crying, people were threatening to punch each other,” this person told me. “I can’t verify this, but we were told there were guns up there and there had been threats with guns, so that was in the back of our heads. If you go there, be careful.”

Daniel Williamson and his wife Kate in their Waipori home. Photo: George Driver.

Waipori Falls wasn’t always like this. In the early 1900s, the Dunedin City Council built the village to house workers from a series of hydro-electric dams on the Waipori River. The council owned all of the infrastructure and residents paid a peppercorn rent. Over the years the settlement grew and by the 1980s about 40 staff and their families lived in a self-sufficient town with its own school, a general store, petrol station, town hall, post office, fire station — even a tennis court and heated swimming pool. Tourists would come on day trips to see the dramatic landscape and walk the popular Crystal Falls track.

But in the early 1990s, the council-owned Dunedin Electricity Ltd decided to either sell off the town or shut it down. In a Holmes segment, the head of the company said it was under pressure to reduce costs, “and the village is a cost that can be eliminated”. For residents, this was devasting news. “I’ve had my best years at Waipori, I think,” one said. A local school pupil called it “the best village in the world”.

In the end it was saved. A developer bought the village and sold off the houses. However, the Clutha District Council, into whose territory Waipori fell, reportedly didn’t want to take on its infrastructure, so the body corp was formed to administer it instead. It was funded by levies on the properties that ranged from about $600 to $5,000 depending on the size and type of the buildings — which quickly pitted neighbour against neighbour.

Former resident Murray Moore owned a crib in the village for 15 years and worked as caretaker there for a while. He says the body corp worked well initially, but disagreements crept in, politics took over and some residents stopped paying their levies. Moore sold up five years ago and, on a recent visit, was shocked to find the village “run down something wicked”.

When I visited in early January, the heated swimming pool had been filled in. The tennis court was overgrown and the Crystal Falls track was closed. People were living in the school, the shop and the fire station. The town hall was growing a layer of lichen; the bush reclaiming two broken lazy-boy chairs and a barbecue in the foyer outside.

The village is on a permanent boil water notice because the filtration system doesn’t work. A large bridge which provides the only access to the drinking water plant closed last year, due to safety concerns. Raw sewage bubbles up through the ground from burst pipes, forming puddles of foul-smelling grey water specked with toilet paper. The roads are potholed and the bush so overgrown it scrapes the sides of my car along the main street, Village Loop Road.

“If you were going to buy over there, the first thing I’d recommend is buy a four-wheel drive,” says Moore. “And I’d say don’t get involved with the politics.”

Curious to find out the extent to which Waipori Falls’ problems could be traced to its unusual governance structure, I called Roger Levie of the Home Owners and Buyers Association (HOBANZ). Levie co-founded the organisation 15 years ago after chairing a body corporate in a building with significant defects. The association now helps leaky building owners and has become an advocate for issues related to multi-unit dwellings and bodies corporate (the awkward plural). When I outlined the situation at Waipori Falls, he said the problems sounded “very familiar”. It was far from the first body corp AGM he’d heard of where security was required.

“People were storming out, people were crying, people were threatening to punch each other.”

Around the country, some 160,000 apartment blocks and subdivisions are governed by bodies corporate. Residents are responsible for millions of dollars of infrastructure, often with little expertise. Factions frequently form, pitting neighbour against neighbour, with everyone’s homes at stake. “It’s human nature,” says Levie. “You’ve usually got a group of owners that take a long-term view and want to spend money to maintain and enhance their assets, and you’ve got others who are looking to not spend money and not worry about the consequences at the other end. So you get this conflict.”

In 2016, an independent working group set up by the government found that people buying into a body corp were often left in the dark about serious issues with the buildings — or villages — they would soon jointly own. It said the pre-settlement disclosure regime was “broken”. People would move into an apartment only to discover they were liable for tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of repair work. Others would find a body corp at war. An elderly, partially blind woman was found dead in a Parnell apartment block in 2016 after she reportedly barricaded herself in after falling out with the building’s body corporate. She refused to vacate to allow workers to complete building repairs, as she feared she would be evicted. The same body corp has taken its owners to the Tenancy Tribunal 53 times to get them to pay levies related to $12 million of repair work.

The working group found there was little in the relevant legislation, the Unit Titles Act 2010, to ensure that committees were doing their job — balancing the books, maintaining infrastructure and working in the interests of the residents rather than themselves. And with multi-unit dwellings increasingly popular in our overcooked housing market — last year, they made up 40 per cent of residential building consents — these issues are only set to escalate.

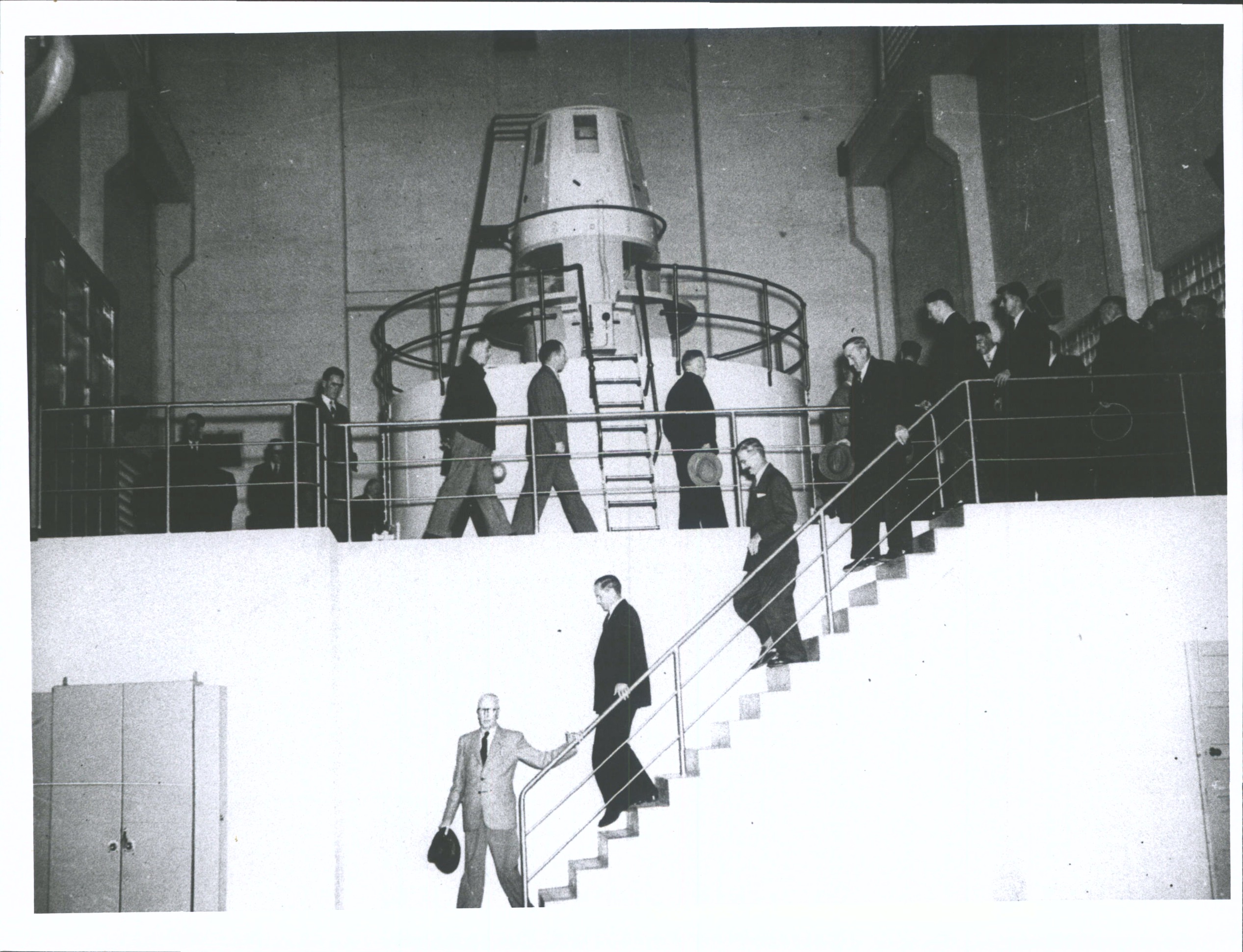

No. 3 station after the official automatic start, Waipori Falls, 26 March 1961. Photo: box-280-007, hocken collections, uare taoka o hākena, university of otago.

Before Michelle Annand moved to Waipori Falls, in 2010, she’d spent 15 years in Aramoana. She lived three doors down from David Gray, who shot 13 people in 1990. Waipori Falls, she says, “is much more scary”.

When Annand bought a three-bedroom home for $90,000, it “looked like a dream situation”, she says. “I guess I was blinkered by the price. And when I went out there I just fell in love with the conservation reserve. I knew zero about anything to do with the body corp or the community.”

Annand became vocal in the campaign to get the levies equalised. She says she started getting death threats and ongoing harassment from other residents. Later, a boundary dispute with her neighbour spiralled into conflict. Annand received a conviction while, she says, she was defending her property. “I got a baseball bat and I flung it around and screamed about.” She got another conviction for emailing her neighbour’s employer, calling her evil and questioning whether she was fit to be employed.

After what she calls a decade of hell, Annand sold her property in 2020. “I was a nervous wreck. I lost my home, I left half of my belongings in my house.” When I spoke to Annand she was living in a tent in Roxburgh, where she was working at an orchard for a few weeks.

Other residents say Annand is prone to exaggeration and that both parties aggravated each other. However, Annand supplied me with emails showing that other residents also left Waipori after experiencing threatening behaviour. And there has been a high turnover in the town. In the last five years, 15 of its 33 houses have changed hands.

Daniel Williamson quit the town’s top job after two years, but the run-ins with other residents have continued. Sitting with his feet up on an antique chair in his lounge, he recounted being knocked out after talking to a group joy-riding on a ride-on lawnmower at 2am. Another day, he says, someone loosened the wheel nuts on his car.

“You can’t deal with anyone here,” Kate chips in from the adjoining sunroom. “This is a nasty, revolting hell hole. I don’t care what anyone says, that’s what it is. It’s horrible.

“If it wasn’t such a nice spot with this house that we like, I wouldn’t live anywhere near these people. It’s horrendous.”

The place does seem like a magnet for drama. In 2014, resident Richard Mathias was woken by dozens of gunshots at 2.45am on a Sunday. He dialled 111, but police from the nearest station, in Mosgiel, never came — they said they didn’t have a spare car to dispatch at that time. In the morning, Mathias found 45 .22 calibre casings. Two street lights had been shot out and a fence was peppered by a shotgun blast. However, Mathias, who left the village in 2016, says it was an isolated incident and he always felt safe in the eight years he lived there.

Others in town also spoke up in its defence. Near the end of a one-way road, Jody Takimoana and his wife Sonja are sitting on the deck of their 1960s three-bedroom crib, soaking in the sun. The couple bought the holiday house for “quite a bit less than $100,000” about 15 years ago and say it’s a great getaway from their Dunedin home. “We love it,” Takimoana says. “We spend holidays and weekends here and it’s so quiet. I suppose it’s different if you’re living here permanently. There’s definitely some interesting dynamics in the community, but I try to stay only as involved as I need to be.”

“It’s bloody paradise,” says pensioner Gary Murphy. He’d always wanted to buy a place in Waipori Falls, but his wife never wanted to live there. Three years ago, after she died, he bought a crib to retire to, although he still spends most of his time in Dunedin, where he works as a truck engineer. He admits that in the last year or so the village has “sort of gone to pack”. “Everybody used to do a bit to keep the place going, but people seem to have lost interest now. People shift out, new ones move in.” Still, he has no plans of selling. “It’s a great place to live,” he insists. “It just needs somebody up there who really knows what they’re doing. People there sort of aren’t experts. They might have an idea but that’s about the guts of it.”

“You only have to come up here and look at the number of bullet holes in the signs and realise . . . some of them can be right mongrels.”

Rod Jansen’s little German pinscher is yapping, up on its hind legs pressed against the front gate when I approach his house, a 1960s three-bedroom with stunning views of the surrounding bush. Eventually Jansen comes out to greet me, a lit rolly cigarette wedged between tattooed fingers on one hand, lighter clasped in the other. He doesn’t invite me in. We talk on the roadside, kererū perching on the powerlines above, his dog barking for attention at our feet.

Jansen was elected as chair of the body corp three years ago, after Daniel Williamson quit. He has a different perspective on life in the village. When Jansen took over, he says the place was poorly run and in debt. Contrary to Williamson’s claims that the village is falling into disrepair, Jansen says the new body corp is turning things around. People are now paying their levies after five residents who collectively owed tens of thousands of dollars were taken to court — one house had to be sold to recoup the debt — and they can now afford to fix up the place. But he says they have had to endure constant criticism from Williamson.

“I’ve been accused of fraud, I’ve been accused of theft, I’ve been accused of corruption. All sorts of shit like this, none of which have transpired into anything. None of us have been prosecuted by the police or even investigated.”

Williamson claims that a lot of the issues with the infrastructure have been caused by residents doing repair work themselves, making costly mistakes. While Jansen concedes some residents helped fix the sewerage system when there was no money — “simple stuff, like replacing old pipes” — that’s no longer the case. “You can tell that stupid fuckwit — and you can print that if you want — all our plumbing work is done by professionals.” As we talk, a resident comes to inform Jansen that water is seeping up from the ground around her house and that muddy water is still flowing from her taps. She has to go to Jansen’s place so she can have a shower.

“These are things that we’re working with,” Jansen tells me.

The infrastructure challenges aren’t helped by occasional acts of vandalism, like the damage to the sewerage plant. But with no police presence, it’s hard to hold people accountable, Jansen says. “You only have to come up here and look at the number of bullet holes in the signs and realise that there are all sorts of people up and down this road and some of them can be right mongrels.”

He maintains the village is a safe place to live. He bought a house to retire to five years ago, moving from Dunedin where he worked as an office assistant for an architecture firm. He was attracted by the nature and the solitude. “It can be problematic when you get people who have got mongrel attitudes, but it generally sorts itself out. You need your neighbours out here.”

It seems like a thankless job, being chairperson. Jansen describes the last three years as “nightmarish”. At times he’s thought about leaving. But it’s hard to find anywhere else like Waipori Falls. “We’re surrounded by bush with waterfalls, great views and you can do just about anything you want out here.”

In May last year, the body corp committee re-elected Jansen as chair by a 13 to 1 vote. Williamson stood for the committee but lost 5 to 9.

“I’ve got my own mission and I’m going to carry on doing it and most people seem to think I’m doing the right thing,” says Jansen. “And I think if you’re not standing alongside me with a shovel doing the work then you ain’t got a leg to stand on. You can sit there and shoot your mouth off from your living room, but you’re not doing the work, so what the fuck do you know about anything? And that’s how I’m operating, you know, and at the moment it works, sort of.”

Waipori town hall. Photo: George Driver.

Last year, a member’s bill was introduced to parliament that could make body corps more regulated and transparent. Under the measure sponsored by National MP Nicola Willis, body corps would have to have a fully funded 30-year maintenance plan reviewed by a professional every three years (Waipori Falls’ 10-year maintenance plan is nine years out of date and entirely unfunded). Prospective buyers would have access to AGM minutes, maintenance plans, audit reports, financial statements and other documents. The bill would also empower the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) to investigate issues raised by body corp members and prosecute when committees are acting unlawfully. In theory, people will be able to know what they’re buying into, and when things go wrong MBIE will step in.

Roger Levie says the changes will address some of the most glaring issues, but he has reservations. “Historically it’s been extremely difficult to get people to behave responsibly,” Levie says. “The amendments go a long way, but it’s only going to be effective if the chief executive of MBIE actually starts using its new powers to ensure the act is being applied.”

It’s difficult to anticipate how the law changes might affect Waipori Falls. Under the reforms, the body corp could still opt out of having a funded and professionally reviewed maintenance plan. When I asked Jansen about it, he was sceptical about the idea of outside oversight. “I don’t know how it would work here,” Jansen says. “When they say professionals, all that means to me is just another group coming out here to make a lot of money.”

Other government policies are likely to bring bigger changes to Waipori. The government’s new water regulator, Taumata Arowai, has been given greater powers to ensure communities have access to safe drinking water. The body corp could become liable for large fines if its water and sewerage aren’t up to scratch.

Conversely, the Three Waters programme may spell the end of the body corp altogether. Under the scheme, water infrastructure currently run by councils will be managed by four government-funded entities. Waipori Falls has asked the Clutha District Council to consider taking on its infrastructure. In theory, the council could take over the assets temporarily, before passing the buck to one of the Three Waters entities in 2024. That would mean Waipori could get its chronic water woes fixed without the village needing to pay a cent. Perhaps the body corp could even be disbanded and the town’s infrastructure finally moved under the authority of the Clutha council.

The council has agreed to investigate what this might cost. Clutha mayor Bryan Cadogan says the village is in “a precarious situation”. “It’s almost Shakespearean, how it’s been set up,” Cadogan says. “You only have to step into the town hall and listen to the community to realise that the challenges they face are more than the infrastructure. There are strong personalities at play. There are historical issues. There’s distrust and discontent . . . We’ve got issues to work through with that community.”

Daniel and Kate Williamson think that if the council took over, it would allow Waipori Falls to be the slice of paradise they thought they were purchasing back in 2016. “It would change the whole dynamic of the place overnight,” Daniel says. “It’s really just been the infrastructure that has been a nightmare. When you get a beautiful day up here and everything’s peaceful, it is paradise. It still enchants us. We would just like the other stuff to be over.”

To Jansen, though, the fundamental issue is that some residents simply have a different vision for what Waipori Falls should be. “Daniel and Kate have this totally unrealistic idea that we are some sort of idealistic artistic community in the fucking wilderness,” he says. “Well, no, we’re not. We’re a very strange little village that’s quite different.”

Waipori Falls road into town. Photo: George Driver.

George Driver is our South Island correspondent. This role is made possible by New Zealand On Air’s Public Interest Journalism Fund.