Four Corners

NATIONAL TREASURES

Thames School of Mines and Mineralogical Museum

Aotearoa is dotted with museums, grand to tiny. In this new, regular feature, we highlight a museum that may not be on your map. Enjoy your visit.

Just two blocks from Thames’ Queen Street stands a trim building of butter-yellow weatherboards and plum corrugated iron. Built in 1886, it housed a mining school. Here, classrooms, laboratories, furnaces and a smelting house are almost exactly as they were more than 100 years ago. In one classroom, wooden pews behind slanted desks face a blackboard to the left, while on the right, a wooden laboratory bench holds iron tripod stands, Bunsen burners and a conical flask.The walls are lined with shelves of glass bottles and beakers.

In front of the school buildings, facing the Firth of Thames, is the adjoining Mineralogical Museum. Its cracked grey façade conceals a bright interior, where each wall is a different colour — green, pink, yellow. Freestanding display cases alternate these same colours. A mint-green table display is pushed against the yellow wall; cabinets along the green wall are pink. The cabinets are collection items in themselves, original and purpose-built of heart kauri to best present the specimens. Inside, geological samples are hand-labelled. Here you will find fossils of extinct marine animals, gold, kauri gum, minerals and a piece of the long-lost eighth wonder of the world.

Elton Fraser, born and bred in Thames and now the Heritage New Zealand property lead, says the museum’s most extraordinary item is easily missed. The chunk of the Pink and White Terraces needs to be pointed out among the overwhelming 3500 specimens in the collection. This rare piece of silica sinter is a heavy handful, blushed pink, and was collected before the eruption of Mount Tarawera in 1886. No one knows exactly how or under what circumstances the rock was obtained — it predates the museum and was donated from a private collection. Fraser notes that this piece, and in fact all of the specimens, are of “a different era”. It is a Victorian and Edwardian collection, from a time when taking from nature was seen very differently.

In the days when the school operated, Thames was the industrial hub of Aotearoa’s gold industry. The mountains were bare, muddy and dug up; the town full of shaft entrances; and stamper batteries crushing gold-bearing quartz thudded day and night, creating an incessant din. Gold mining is central to history here — without gold, there would be no Thames. And the young settlement was heaving: people hustled, hospitality bustled with hotels on every corner, world-class engineering firms came to stay, and ships made regular trips to Auckland. Thames grew into a large industrialised town, its population competing with that of Auckland. Most families long resident in the area have some connection to mining. Many of Fraser’s relatives, for instance, attended the School of Mines, and his great-great-grandfather managed a goldmine.

Here you will find fossils of extinct marine animals, gold, kauri gum, minerals and a piece of the long-lost eighth wonder of the world.

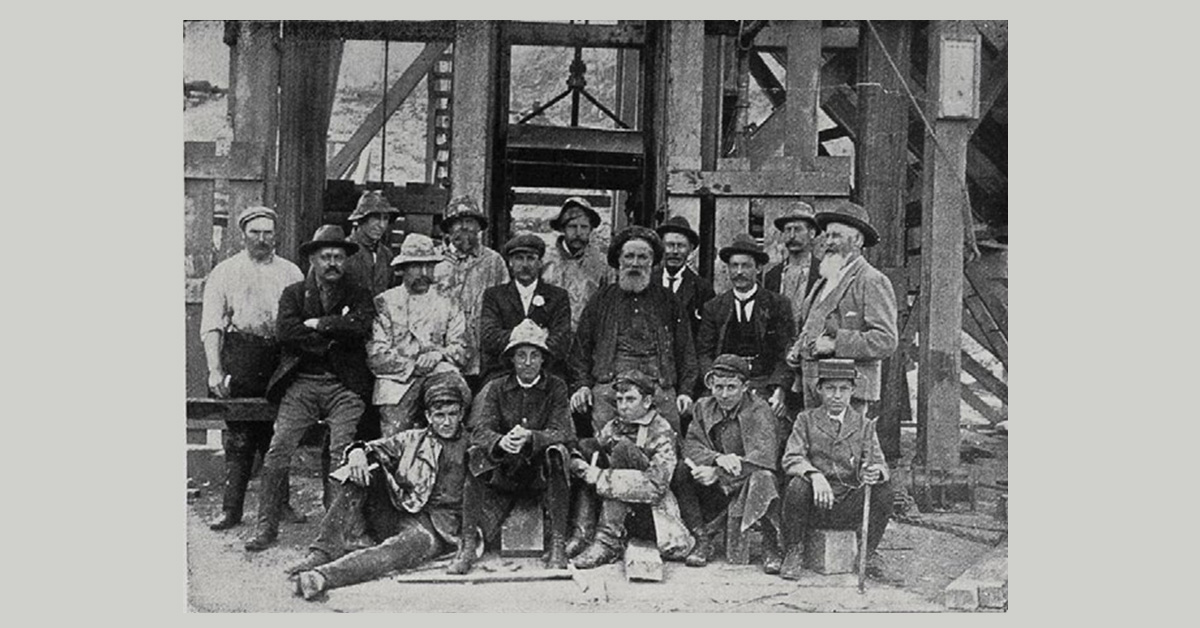

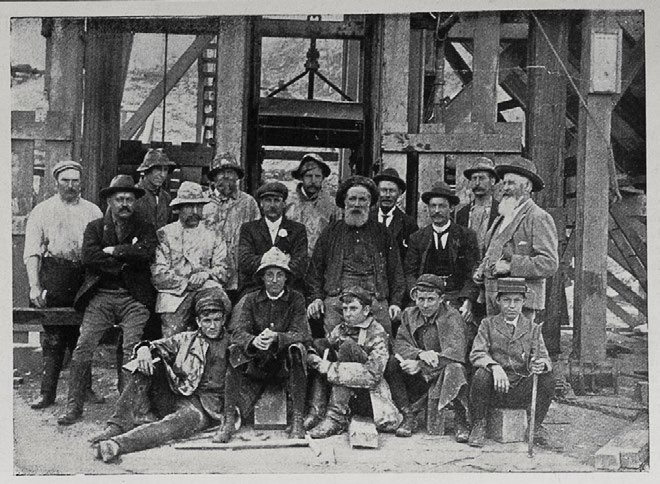

Pupils of the school were pictured in the Auckland Weekly News on 12 December 1901 as they prepared to descend the gold mining shaft at Opitonui.

As gold mining declined, the school attempted to remain relevant by expanding its offerings, but its doors closed in 1954. The site passed to the Thames Borough Council, which did not know what to do with it. The then-mayor thought the buildings were useless and suggested demolition. Instead, local mining agent, accountant, historian and author Alistair Isdale stepped up in 1960, reopening the Mineralogical Museum. Isdale is remembered as a grandfatherly figure by Fraser, who grew up on the same street where Isdale grew old. He kept to himself, but was respected by the community: “Everyone knew he worked at the School of Mines.”

While the future of the buildings and their contents remained uncertain, they also remained intact, as there was no desire to adapt, or update them. Temporary commercial leases in 1959 and 1971 kept demolition at bay. When in 1976 the council decided to demolish the battery room, the New Zealand Historic Places Trust (now Heritage New Zealand) ensured its preservation with funding. Then, in 1979, Historic Places purchased the entire Thames School of Mines complex. Teams of volunteers and staff have worked to maintain and keep the school and museum open to the public ever since.

In 2004, the site was recognised as wāhi tapu, as underneath the school is an urupā. In the 1860s the land had been gifted to the Wesleyan Church by Hohepa Paraone and Hone Te Huiraukura of Ngāti Maru to be used for religious purposes, but the Wesleyans on-sold it against their wishes. Visitors to the museum and school are made cognisant of the significance of the place and asked not to eat or drink on the premises. Today the mountains behind Thames are dark with bush, most of the hotels have closed, and the traffic on the main road is mostly passing through. Mining is a controversial subject on the Coromandel Peninsula, and Fraser, while endlessly enthusiastic about Thames School of Mines and the museum, is an environmentalist. For him the school’s value is the near perfect preservation of the past. “It’s just like stepping back in time,” he says. “Can you imagine the coal being burned?”

As mining declined, the subjects taught were diversified, offering courses in agricultural science, engineering, mechanical drawing and mathematics, as well as accepting female students. Photo: Grant Sheehan.

These bottles once held chemicals such as hydrochloric acid, mercury and ammonium persulphate for analysis of different chemicals, removed for health and safety purposes. Photo: Grant Sheehan.

Gabi Lardies is a The Next Page intern, a role funded by NZ On Air’s Public Interest Journalism.