BACKSTORY

Melanesians working in Queensland cane fields like these made the state wealthy — but their stories were often unhappy ones. Photo: City libraries Townsville.

Beyond the Badlands

Strange monsters and ominous ghosts can be traced to repressed memories of violent histories, argues one Australian researcher looking at the past through a novel lens.

By Scott Hamilton

Academic historians sometimes think of the past as a set of books on a shelf: a tidy collection of facts, timelines and narratives. But few academic histories, no matter how excellent, become bestsellers — many of us prefer to understand the past in other ways.

When I was growing up in the farming country that borders the southern edge of Auckland, the past made itself present through ghost stories and superstitions.

There was an old coal shaft in the Drury Hills, where spirits of lost miners were said to whistle and howl. There was a bush-covered pā beside a waterfall, whose pūriri trees had been saved because they contained bones of the dead. There were places on straight flat roads where speeding bikies and drunken walkers had been struck and killed by passing vehicles. Motorists slowed superstitiously when they reached these unlucky stretches of road.

Historians have usually been unwilling or unable to connect ghostly folklore like this to the facts and events of the past. How, after all, can what is ephemeral and mysterious be documented and tested and inserted into an historical narrative?

The most exciting book I read last year was Ross Gibson’s Seven Versions of an Australian Badland. Gibson is a professor of creative and cultural research at the University of Canberra. With Badland, he has found a way to connect the ghost and monster stories he learned as a kid to the timeline of antipodean history.

The “badland” Gibson writes about is a road that runs from Rockhampton to Mackay, through bush, scrub and plantations. The road has been the site of a series of murders and kidnappings, often involving people from beyond Queensland’s borders. Ghosts appear in car headlights. The Yowie — a hirsute, ape-like creature — is said to roam the forests the road cuts through.

Gibson explains the violent 19th-century history of the regions the road connects. Aboriginal peoples were massacred there, and later Melanesians stolen or tricked away from the islands of Vanuatu and the Solomons were put to work in land cleared from the bush. Thousands of them died from diseases and overwork, as they planted the fields of sugarcane that would eventually make Queensland wealthy.

As the decades passed, floods and erosion damaged the denuded land. Some farms slid into rivers, and floated out to sea. While some farmers prospered, others went mad or committed suicide.

In 1901 the federal government adopted a “White Australia” policy, and tried to deport Melanesians en masse. Former slaves who had found work and built homes for themselves were put on ships. A minority escaped, and hid in the bush for years. When they returned, they often pretended to be Aboriginals. It was only in the 1970s that the Australian government recognised the existence of the descendants of the sugar slaves.

Ghosts appear on the stretch of Queensland road in car headlights. The Yowie — a hirsute, ape-like creature — is said to roam the forests the road cuts through.

In Totem and Taboo, his first book about history, Sigmund Freud insisted that no act of violence could be permanently repressed by its perpetrator. Humans may try to forget their evil deeds, but the memories they bury will resurrect, often in new forms.

Gibson says the white 19th-century pioneers were haunted by their violent acts against black people. He looks at old family photographs, and sees wide frightened eyes staring back at him. The deportations of the early 20th century and the racial segregation that became systematic were attempts to repress memories of a non-white Other that the white colonists associated with disorder and disaster.

But these attempts at repression inevitably failed. The repressed returned in nightmares and anxiety attacks: as a darkness inside the settlers. One way to deal with the presence of the Other was to banish it to a badland.

Gibson argues that by making the “horror stretch” of road from Rockhampton to Mackay into a badland, where alien people did inexplicable things and surreal sights were ordinary, white Queenslanders tried to deal with the unease they felt at their own history and at the continuing presence of the unassimilated in their state.

Numerous experiments have shown that the human mind is very suggestible. Our perceptions are in part guesses about our surroundings. When we are told a place is haunted, our minds may respond by summoning a sense of dread, and even by creating hallucinations. We give special weight to mishaps and tragedies that occur in this place. Gibson argues that, on the road from Rockhampton to Mackay, the repressed returns to haunt the settler mind.

New Zealand’s old newspapers teem with accounts of ghosts and monsters and other supernatural phenomena. Gibson’s book offers a model with which to begin to understand these things.

One of the most remarkable mass hallucinations in New Zealand history was the “Waikato saurian” of the 1880s. Hundreds of white settlers in the area reported seeing and hearing a monster. The monster sometimes resembled a huge lizard, and at other times had long, black, shaggy hair. It always boasted huge jaws and jagged teeth. Sometimes it was seen in rivers and drains; sometimes it roamed on land.

In late October 1886 newspapers reported that the saurian had attacked Frankton’s slaughter yard and devoured a sheep. It left tracks “unlike those of any animal”, according to the Thames Advertiser. A month later the Thames Star ran the headline “The Saurian Monster is Coming!” after the creature was seen diving into the Ohinemuri River at Paeroa and heading north. In February 1888 the monster surfaced in the Waikato River, and tried to sink a canoe. The canoeists fell overboard, and were swept dangerously close to the rapids of Arapuni Gorge.

Bands of settlers began to hunt the Waikato Saurian, carrying the guns they had recently aimed at Waikato Māori. Some papers blamed the Waikato’s indigenous people for the exotic creature: they talked of parties of Māori travelling to Australia, returning with alligator eggs, and leaving those eggs on the banks of the Waikato to hatch. The fact that there were no alligators in Australia only made the allegation more surreal.

Following Gibson’s example, we should examine the real history of the Waikato to try to understand the monster of the 1880s. The Waikato was a thriving Māori kingdom until imperial troops crossed its northern border in the middle of 1863. The kingdom’s forts and capital were stormed. Its urupā were desecrated and its wheatfields burned. Its maunga and kāinga got new, imperial names. Awa were turned into canals and drains. Vast kūmara gardens were subdivided into grids of farms for soldier-settlers. Pā became redoubts for colonial militia. Memories were repressed, ghosts buried.

Most of the settlers had fought in the invasion, and had been rewarded with parcels of confiscated land. Letters and poems written by these settlers talk of isolation, uncertainty and melancholy. Perhaps the monster of the 19th century was a manifestation of the fears of the Pākehā settlers of a strange and stolen land. They had renamed places, demolished wāhi tapu and terraformed the landscape, but the monster defied all these efforts at repression.

Another set of weird reports emerged from the small town of Waihī in the 1920s. A ghost stalked the town in those years, scaring adults and children alike. The ghost had a “masked shining face” and clothes “lit up by phosphorus”. In 1927 newspapers reported that a militia of 40 men had been formed to patrol the town and capture the invader.

Why did this supernatural terror afflict Waihī, in particular, in the 20s? It is interesting to recall that the residents of the town then were mostly strike breakers who had arrived in 1912. In that year, the town’s gold miners had gone on strike for better wages. They belonged to the militant “Red” Federation of Labour. When they were brought into town to take over the empty mine, the strike breakers were denounced and sometimes attacked by the strikers.

Many strike breakers were signed up as “special constables” — that is, temporary untrained police — by a government determined to defeat the strikers. In November 1912 a young member of the Red Federation named Fred Evans was attacked by intoxicated special police outside Waihī’s union hall. He died after being hit with a baton and with boots and fists. After Evans’ death the government and the strike breakers solidified their hold on Waihī. Trade unionists were driven out of the town.

Did Waihī residents, in the 1920s, experience a return of the repressed? Were they, as well as the soldier-settlers, haunted by a symbol of their enemy?

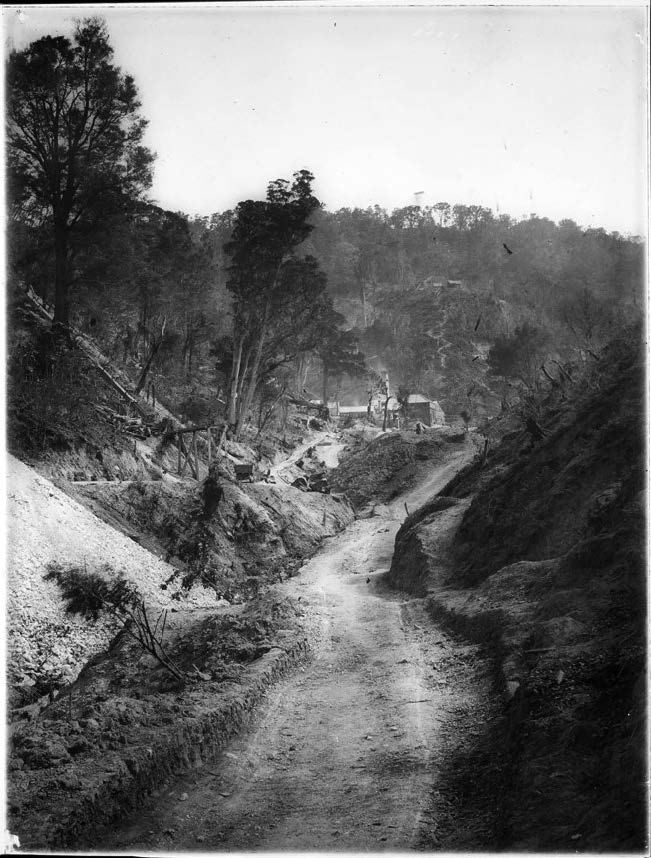

Moanataiari mines, Thames — site of a miner ghost. Photo: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 4-3678.

Scott Hamilton is an historian and writer living in Auckland.

This story appeared in the May 2022 issue of North & South.